The Artist as Egomaniac

A Reckoning?

The Artist as Egomaniac

A Reckoning?

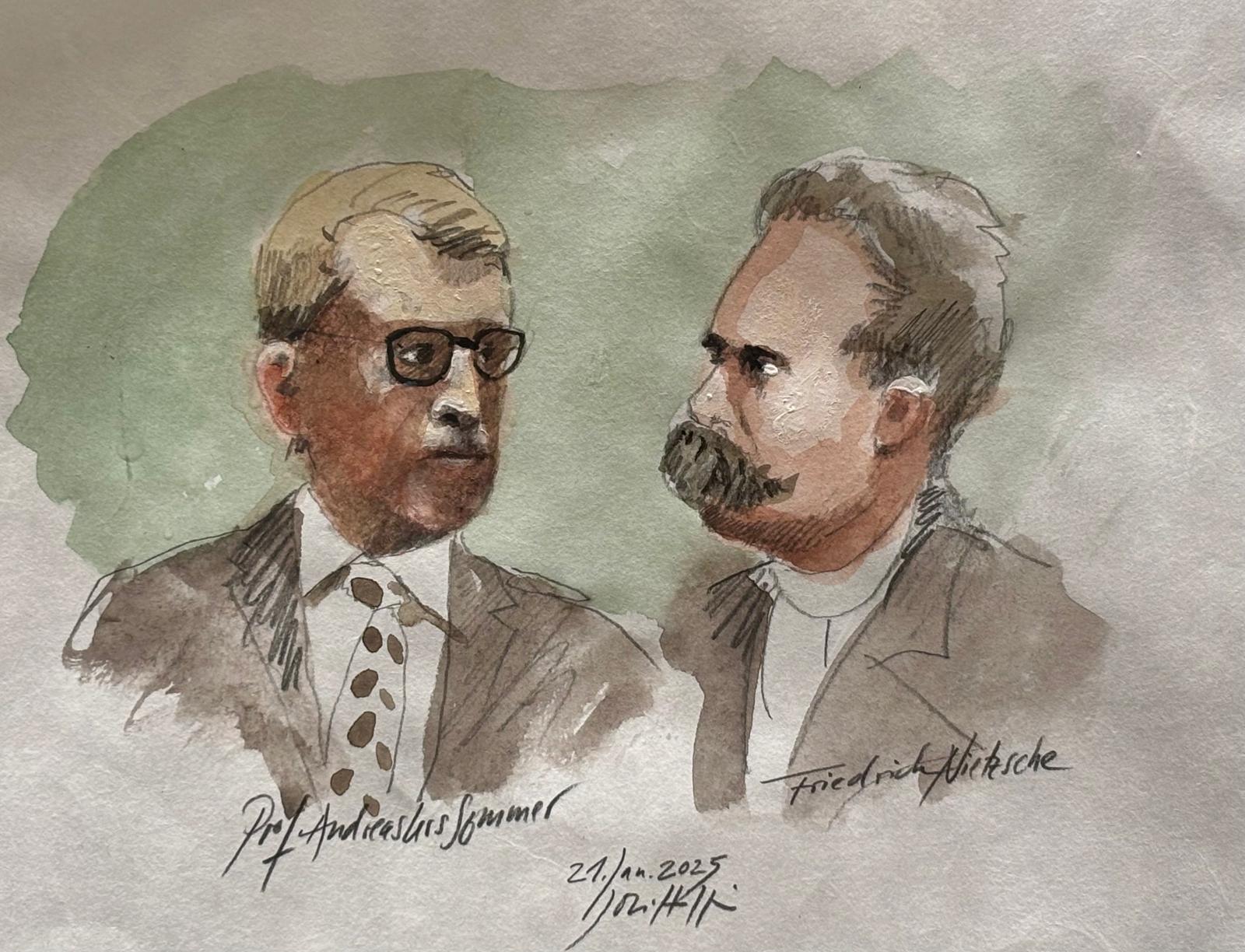

Artists often do not come off well in Nietzsche’s work. They represent the prototype of the dependent, truth-hostile and reality-denying person who is at the mercy of his own moods without self-control. A childish, dramatizing, hot-tempered and generally ridiculous creature, an egomaniac whose actions and demeanor are aimed solely at courting the applause of others. Or is Nietzsche not taking his word for it here? Should this really be his final verdict about the creative spirit?

He develops much of what Nietzsche describes about the artist on the figure Richard Wagner, with whom he has a brief, intensive, but ultimately disappointing acquaintance. The artist and the thinker could have been the ideal friendship for Nietzsche for a while. But after breaking with Wagner, Nietzsche has a lot of derogatory things to say about the artist as a type. How different — for comparison — is the friendship between artist and thinker in Narcissus and Goldmund by Hermann Hesse, who deals extensively with Nietzsche.

One of the most famous literary dichotomies, which juxtapose the type of artist with that of the thinker, is probably Hermann Hesse Narcissus and Goldmund. Hesse, one of the many writers who studied Nietzsche's work intensively in the 20th century, wrote in his novel published in 1930 about the fulfilling friendship of two opposing figures — the thinker Narcissus and the artist Goldmund. Their acquaintance enables them to make progress in areas they have neglected so far, emotional attachment with Narcissus, self-knowledge with Goldmund. According to their nature, their time together is only temporary, because Goldmund is drawn into the world, while the outer life for Narcissus as the type of introvert is only burden and imposition, and is therefore best kept in the monastery. The admiration that the two characters have for each other always comes full circle. If Goldmund first admires Narcissus's cleverness and seriousness, Narcissus is immediately enthralled by the beautiful, lively boy Goldmund. Although Hesse later writes that he does not want his two characters to be understood as merely schematic types of the artist as a sensory person and the thinker as a spirit person, they are nevertheless sharply differentiated from one another.

Narcissus once clairvoyantly summarizes the meaning of their friendship: “Our goal is not to blend into one another, but to recognize one another and learn to see and honor each other for what he is: the counterpart and complement of the other. ”1

You could imagine that Nietzsche would have wanted his friendship with the artist Wagner to be something like that. However, from the outset, she had little intention of becoming a relationship on equal terms, since Nietzsche was a young, unknown academic of 24 years of age and Wagner a famous and controversial artist of 55. Much has been written about the failed friendship, if anyone wants to call it as such, much about Nietzsche's wishes, his hopes and his disappointment. You may even be tempted to project everything that Nietzsche has written about the artist onto Wagner; Nietzsche himself gives reason to do so when he, in his work, which significantly The Wagner Case means, writes that he is the ultimate type of Decadence artist (cf. Paragraph 5). Further details from Nietzsche's biography, such as the early loss of father, hard-working interpreters speculation about a transferred Oedipus complex and other psychological imbalances in the person of Friedrich Nietzsche.

For Nietzsche, it must be admitted, the artist is often the musician, but also the poet and — although more rarely explicitly — the visual artist. The ideas that Nietzsche has about characters such as Goethe, Beethoven, Shakespeare, Lord Byron, Stendhal, Michelangelo and many more relate, we may assume, to his type of artist as the figure of Richard Wagner solidified into a statue. We may even be tempted to assume that instead of reading the artist as Wagner, the other way around, names such as “Wagner” and “Schopenhauer” no longer mean the people Wagner or Schopenhauer, but become ciphers for subspecies within the type of artist or philosopher. Only when we understand Nietzsche's figures of thought in this way do they become controversial for the analysis of people and possibly even for our own self-image, provided that you have artistic ambitions or see yourself as a learned or contemplative person.

The artist with bad character

The dreamy, sensitive charisma that Hesse gives to his artistic protagonist seems far removed from Nietzsche's artistic character, as he did in the Morgenröthe, Aph 41, because “as persons [they were] mostly indiscriminate, moody, envious, violent, unpeaceful.” Instead of searching for themselves, going their own way and risking contempt, they are often only the first in the wake of a ruler, particularly eloquent flatters and finally nothing more than minions of the court.2 The artist, as Nietzsche also writes in the The genealogy of morality, is unable to stand alone, he cannot create a primary thought figure or an ideal, he must borrow one from the thinker and project his art into this ideal.3 The strong emotional world, the depth of vision that you attribute to him, not least because you see depth and complexity in his work, is not necessarily a real characteristic of him. In his moodiness, his aggression, the artist was affected, he exaggerated his feelings because it was expected of him and it served the cult of genius.4 But where he shines the deepest in his work, where he draws a beautiful and noble soul, moral motifs and materials, that is exactly where he only looked with a glass eye, “with the very rare success that this eye finally becomes living nature, albeit somewhat atrophied looking nature, — but with the usual success that all the world thinks of seeing nature where cold glass is.”5.

The infantile artist

Time and again, Nietzsche portrays the artist as a childlike character, as someone who only wants to play, who is selfish, who cannot really see or recognize others because he constantly only revolves around himself and only uses others as reflectors for his own admiration. Nietzsche, who described the game and the experiment in numerous aphorisms of Morgenröthe, who Happy science and in Zarathustra enhances, but writes in Human all too human critical of this:

In itself, the artist is already a lagging behind, because he stops playing, which belongs to adolescence and childhood: in addition, he is gradually being drawn back to other times. This ultimately results in a fierce antagonism between him and the people of his period of the same age and a gloomy end [.]6

The artist as an enemy of truth

The artist resists growing up; instead of cool reason making the world and life explainable and predictable, he wants to go back to earlier times. He certainly doesn't want to let magical thinking be taken away from him. More distant times — Nietzsche here associates the young age in which the artist remains stuck with the still young humanity — are closer to him.7 The step towards reason was not completed; gods, demons and spirits ruled an incomprehensible and chaotic world that needed a magician. This is the real Nietzsche taste of the artist and even though it is obscured, it is reflected in the artist's natural aversion to science. He hates science and at the same time envies it because it is the modern magician who makes new achievements possible. But if the artist now yearns to return to this old world of ghosts and fairies, it is not because he really believes in these magical things or even in a god — Nietzsche never tires of antithetically juxtaposing art and faith — not because he thinks he has a truth in them, no, he actually just wants to optimize his own conditions of existence and creation and this is “the fantastic, mythical, uncertain, extreme, the sense of the symbolic, the overestimation of the person, the belief in something miraculous in genius.”8.

The artist as an enemy of reality

Finally, and this is probably the sharpest reproach, the artist in Nietzsche is not a person of the real world. Because it is a lack of reality that makes him an artist; he invents heroes that he cannot embody himself:

In fact, it is true that, when That is exactly what he would not represent, think it out, express it; a Homer would not have composed Achill, a Goethe would not have composed a Faust if Homer had been an Achill and if Goethe had been a Faust. A perfect and complete artist is separated from the “real,” the real, for all eternity [.]9

But if the artist were at least able to differentiate between his fantasies and his person and their substance, perhaps a last remnant of respect for him would be maintained. But unfortunately, this type of person is heavily dependent on the evaluation and respect of others who, as one must fairly add, can easily be seduced into seeing in the artist something of the hero he invented. The cult of genius that develops around the artist relieves ordinary people of the task of finding a work for themselves.10 If a work can only be created by a genius, then every attempt made by yourself is a mere waste of time. But nothing inflates the artist's self-confidence more than such an interpretation. Admiration acts like a drug on him. He wants to be more and more, portray and be admired by more and more people. This not only spoils his art, which descends to a “mob,” but also his personality, which degenerates into a mere mask. As an actor, the artist loses his substantial personality. He is never what he represents, but he can no longer do anything but represent.11

Is the artist mentally disturbed?

Finally, we could therefore say that Nietzsche paints a highly pathological picture of the artist which, according to today's trivial psychology, should correspond to the narcissist's personality disorder: egocentric, childish and charismatic. Depending on the occasion, when he can afford it, moody, with impulse control disorders, changeable in his affections. Fluctuating in his own self-assessment between delusions of grandeur and inferiority, forced to seduce others to himself in order to then believe in his own grandiosity, which he cannot take away from himself. Every moral conscience is naturally alien to him or at best a piece of disguise in the rich range of masquerades.

But this would of course not be Nietzsche's philosophy if things were so simple and you couldn't also tilt this image into a tipping ratio. In Hesse, artists and thinkers are sharply differentiated from each other as types of vita activa and vita contemplativa, but in Nietzsche they seem to have a common intersection. With Nietzsche, the philosopher is the consistent continuation of the ascetic priest and even the artist only seems to have taken a different path at a fork in the road. All the negative character traits Nietzsche had in the Morgenröthe 41, he assigns to a type of artist that grows out of the contemplative. And the type of thinker, well, he doesn't fare much better with Nietzsche either. For he combines the bad character traits of the artist with the priest's tendency to make others grumpy and puts a third bad quality on top of that: With their dialectical thought processes, they also cause other people a lot of boredom.12

Yes, even philosophers don't seem far off in their love for truth. The ideals that philosophers have highly praised — mostly ascetic ideals of abstinence, lack of possession, etc. — are only the best basis for their own work:

Freedom from coercion, disturbance, noise, business, duties, worries; brightness in the head; dance, jump and flight of thought; good air, thin, clear, free, dry, like the air at heights, in which all animal beings become more spiritual and gain wings [.]13

That is, where the artist pushes back into a magical world in which he is transfigured as a mediator between the world of God and the human world, the philosopher in the direction of an ivory tower, from where he can perceive everything perfectly without being plagued by everyday impositions.

But is this really still a critique of the artist or thinker or is it rather a critique of the naive belief in supra-personal truth and timeless ideals? Affirming one's own living conditions and not a truth that is potentially hostile to life could unite both artists and smarter thinkers. And when other people get on the glue of artists and thinkers, believe their ideals as eternal, admire them, pay for them and do coarser, boring activities themselves, because they don't see a genius in themselves that they regard as necessary for being an artist, and yes, when they practice abstinence and meditation for a while without doing them any good, well, what do artists and thinkers care about? They need it, appearance and aura, to preserve themselves if the world does not require them to pursue an honorable bread job. And last but not least, the artists and thinkers of the world thank them for making them more beautiful and enriching them with stories and poetry, or presenting ideas and ideals that inspire people.

The less convincing an objective truth that is valid for all people in terms of timeless ideals and values, the closer artists and thinkers get to Nietzsche. After all, the thinker is perhaps nothing more than an artist who creates values and ideals, just as the painter paints his picture and the sculptor frees the sculpture from the stone. Both types start from the common field of the contemplative, from the observer, introvert, inactive and brooder,14 But the creative power gives them an activity which is the simple Vita activa surpasses. Nietzsche gives her a new name: the Vis creativa. The poetic thinker, the artist-philosopher initially underestimates himself:

[E] r means as viewers and listeners To be faced with the big acting and sound play that life is: he calls his nature a contemplative and in doing so overlooks the fact that he himself is also the actual poet and perpetrator of life — that he is, of course, away from actors This drama, the so-called acting person, is very different, but even more from a mere observer and guest with the stage. As the poet, he certainly has vis contemplativa and a look back at his work, but at the same time and for now the vis creativa, which the acting person missing, whatever appearances and everyday beliefs may say. It is we, the thinkers, who really and always have something making, which is not yet there: the entire ever-growing world of estimates, colors, weights, perspectives, step ladders, affirmations and negations. This poetry invented by us is constantly being taught by the so-called practical people (our actors, as I said), translated into flesh and reality, even everyday life. What only Werth In the present world, that does not have him in itself, in his nature — nature is always worthless: — but value has been given to him once, given, and we were these givers and givers! First we have the world That concerns people, created!15

In his philosophy, Nietzsche gives thought radical power. By developing new ways of looking at the world by already focusing their attention on certain areas of life and neglecting others, philosophers, even if they still think of describing, value some things and others. Philosophers and priests are thus giving people new role models; they are screenwriters for the real world. And what about the artists now? With the cult of genius, they only seem to relieve people of their own creative attempts. So do they keep people small? Well, that would probably be an unfair view, because artists in particular upgrade entire emotional worlds, options for action, heroic stories. One would have to conclude from Nietzsche's philosophy that they first enable completely new sensations that you did not experience at all before. Nervousness, romantic love, sensibility — aren't these artists' inventions? Nietzsche might have objected that, according to his theory, artists cannot stand alone, that they must borrow an ideal from someone else. Assuming this was true, the artists would still be the ones who transform a piece of pale theory into fire and flame and first awaken the desire that makes people move in other directions. From time to time, there may even be a favorable coincidence: an artistic philosopher, a philosophical artist — and, in addition, the possibility of friendship between one and the other.

Sources

Hesse, Hermann: Narcissus and Goldmund. Frankfurt am Main 1978.

Footnotes

1: Hesse, Narcissus and Goldmund, P. 44.

2: Cf. On the genealogy of morality, III, 5.

3: See ibid.

4: Cf. Human, all-too-human I, 211.

5: Human, all-too-human II, Mixed opinions and sayings, 151.

6: Human, all-too-human I, 159.

7: See ibid.

8: Human, All Too Human I, 146. See also the aphorisms 147 and 155 in the same book.

9: On the genealogy of morality, III, 4.

10: Cf. Human, all-too-human I, 162.

11: Cf. So Zarathustra spoke, The magician.

12: See ibid.

13: On the genealogy of morality, III, 8.