Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche‘s Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche's Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

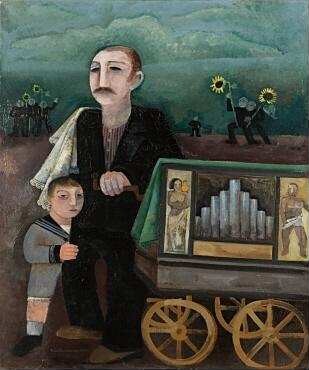

Last week, Emma Schunack reported on this year's annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society on the topic Nietzsche's technologies (link). In addition, in his article this week, Paul Stephan explores how Nietzsche uses the machine as a metaphor. The findings of his philological deep drilling through Nietzsche's writings: While in his early writings he builds on Romantic machine criticism and describes the machine as a threat to humanity and authenticity, from 1875, initially in his letters, a surprising turn takes place. Even though Nietzsche still occasionally builds on the old opposition of man and machine, he now initially describes himself as a machine and finally even advocates a fusion up to the identification of subject and apparatus, thinks becoming oneself as becoming a machine. This is due to Nietzsche's gradual general departure from the humanist ideals of his early and middle creative period and the increasing “obscuration” of his thinking — not least the discovery of the idea of “eternal return.” A critique of the capitalist social machine becomes its radical affirmation — amor fati as amor machinae.

Nietzsche's cultural criticism is extremely ambivalent in its orientation towards modernity. Sometimes it seems as if he represents an almost modernist point of view, sometimes he tends towards the Romantic or even the reactionary. In order to visualize this ambiguity of Nietzsche's cultural criticism and his position on modernity, it is extremely instructive to look at his statements on the term “machine.” This allows, not least, a more nuanced view of his ethics of authenticity.

I. A Fighter against Machine Time

Statements in which he criticizes the machine and uses it as a metaphor for modern capitalism run like a common thread throughout Nietzsche's work from the earliest to the latest writings. He criticizes, for example, that the modern “external academic apparatus, [...] the educational machine of the university put into action.”1 Reduce scholars to mere machines like factory workers.2 Modern philosophers are “machines of thinking, writing and speaking”3. In a similar way to Karl Marx, Nietzsche even criticizes the subjugation of workers in this period, who are forced to “rent themselves out as physical machines.”4, himself under the machinery and blames them for their moral degeneration or for the sprouting of what he would later call “resentment”:

The machine terribly controls that everything is happening at the right time and in the right way. The worker obeys the blind despot; he is more than his slave. The machine Does not educate the will to self-control. It awakens a desire to react to despotism — debauchery, nonsense, intoxication. The machine evokes Saturnalia.5

Elsewhere, Nietzsche formulates the dialectic of machinization as follows:

Reaction against machine culture. — The machine, itself a product of the highest thinking power, sets in motion almost only the lower thoughtless forces of the people who operate it. In doing so, it unleashes an immense amount of power that would otherwise lie asleep, that is true; but it does not give the impetus to climb higher, to improve, to become an artist. She makes Acting and monoform, — in the long run, however, this creates a countereffect, a desperate boredom of the soul, which learns to thirst for varied idleness through it.6

Machinery thus serves as an educator of inauthenticity, producing flexible machine people who are unable to educate themselves:

The wild animals should learn to look away from themselves and try to live in others (or God), forgetting themselves as much as possible! They feel better that way! Our moral tendency is still that of wild animals! They should become tools of large machines besides them and would rather turn the wheel than be with themselves. Morality has been a challenge so far Not to deal with yourselfby shifting your mind and stealing time, time and energy. Working yourself down, tiring yourself, wearing the yoke under the concept of duty or fear of hell — great slave labor was morality: with the fear of the ego.7

Even in his late work, Nietzsche considered submission to the “tremendous machinery”8 of the “so-called 'civilization'” (ibid.) — its main features: “the reduction, the ability to pain, the restlessness, the haste, the hustle and bustle” (ibid.) — as the main reason for “the The rise of pessimism“(ibid.). He speaks disparagingly of the arbitrarily fungible “small [n] machines”9 of modern scholars and ridicules the fact that it is the task of the modern “higher education system”10 Be, “[a] us to make a machine for man” (ibid.), a dutiful “state official” (ibid.) as a, supposed, complete manifestation of Kant's ethics. When viewed honestly

That wasteful and disastrous period of the Renaissance turns out to be the last large time, and we, we modernity with our fearful self-care and charity, with our virtues of work, unpretentiousness, legality, scientificity — collecting, economic, machinal — as a faint Time [.]11

And last but not least, he speaks in Ecce homo about the “treatment I receive from my mother and sister”12 as a “perfect [r] hell machine” (ibid.).

The estate of the early 1870s even states programmatically:

handicraft learning, the necessary return of the person in need of education to the smallest circle, which he idealizes as much as possible. Combating the abstract production of machines and factories. To create ridicule and hate against what is now considered “education”: by opposing more mature education.13

The modern utilitarian machine world is Nietzsche in its totality a horror, which he critically confronts with the Dionysian culture of antiquity:

Antiquity is in its entirety the age of talent for Festfreude. The thousand reasons to rejoice were not discovered without acumen and great thought; a good part of the brain activity, which is now focused on the invention of machines, on solving scientific problems, was aimed at increasing sources of joy: the feeling, the effect should be turned into something pleasant, we change the causes of suffering, we are prophylactic [precautionary; PS], that palliative [“wrapping in the sense of palliative care; PS].14

In the machine world, people surround themselves with anonymous goods instead of real things, through which they could enter into a resonating relationship with their originators:

How does the machine humble. — The machine is impersonal, it deprives the piece of work of its pride, its individual Good and faulty, which sticks to all non-machine work — that is, its bit of humanity. In the past, everything buying from artisans was a Marking people, with whose badge you surrounded yourself: the household and clothing thus became a symbol of mutual appreciation and personal belonging, while now we only seem to live in the midst of anonymous and impersonal sclaventhum. — You don't have to buy the ease of work.15

In contrast to personally manufactured, authentic, artisanal products, the mechanical goods did not impress with their intrinsic quality, as could only be determined by experts, but only through their effect and thus deceive the general public.16

However, Nietzsche summarizes this comprehensive critique of modern commodity production and the world of life bewitched by it most harshly in Human, all-too-human together:

Thought of Discontent. — People are like coal mines in the forest. Only when young people have burned out and are charred, like them, will they usefully. As long as they steam and smoke, they may be more interesting, but useless and even too often uncomfortable. — Humanity mercilessly uses each individual as material to heat its large machines: but why use the machines when all individuals (i.e. humanity) only use them to maintain them? Machines that are their own purpose — is that the umana commedia [human comedy; PS]?17

The proximity of these ideas to a Rousseauist, romantic critique of capitalism, but also to Marx, is remarkable and obvious. For Nietzsche, the “machine” becomes the epitome of what Marxism describes as the “fetishism of commodity production” and he comes surprisingly close to a clear understanding of the rederizing mechanisms of the capitalist mode of production here. — Of course, this metaphor is not astonishing in view of the fact that the valorization of “authentic production” over craft into the “absolute metaphors” (Hans Blumenberg) of modern thinking of authenticity On whose tracks Nietzsche moves completely at these points. The living and the dead, the machine and real practice, are juxtaposed in a harsh dualistic way.18

In view of these clear words, it is significant that, in parallel, there was an almost diametral revaluation of the machine in Nietzsche's writings from around 1875.

II. Man as a Machine

Remarkably, this first takes place in Nietzsche's letters. Between 1875 and 1888, he repeatedly referred to his own body or even himself as a “machine” in them and reported on their good or poor functioning.19 In this sense, he already speaks in the Morgenröthe in a purely descriptive sense of the body in general as a machine20 and is also moving on to calling humanity as such in a neutral way.21 Here he apparently draws on the naturalistic wing of the Enlightenment, such as Julien Offray de La Mettries L'homme machine (Man as a machine, 1748), as part of his generally growing interest in naturalistic explanations of human behavior in that period.

Already in Human, all-too-human Nietzsche admiringly compares Greek culture with a speeding machine whose tremendous speed made it susceptible to the slightest disturbances.22 In the estate of the 1880s, Nietzsche then just as uncritically designed a “depiction of the machine 'man'”23 and moves on to seeing something good in the machinization of humanity:

The need to prove that to an ever more economic consumption of people and humanity, to an ever more closely intertwined “machinery” of interests and services A countermovement belongs. I refer to the same as Elimination of humanity's luxury surplus: It should bring to light a stronger species, a higher type, which has different conditions of origin and conservation than the average human being. My term, my allegory For this type, [...] is the word “superman.”

That first path [...] results in adaptation, flattening out, higher Chineseness, instinct modesty, satisfaction in reducing people — a kind of stoppage in Human level. Once we have the unavoidably imminent overall economic administration of the earth, then humanity can find its best meaning as machinery at its service: as a tremendous train of ever smaller, ever finer “adapted” wheels; as an ever increasing superfluence of all dominant and commanding elements; as a whole of tremendous power whose individual factors Minimal powers, minimal values represent. In contrast to this reduction and adaptation of the M <enschen>to a more specialized utility, the reverse movement is required — the generation of synthetic, of buzzing, ofthe justifying People for whom this machinalization of humanity is a precondition of existence, as a base on which he can his Higher form of being Can invent yourself...

He just as much needs the antagonism the crowd, the “leveled”, the sense of distance compared to them; he likes them, he lives from them. This higher form of aristocratism is that of the future. — Morally speaking, that overall machinery, the solidarity of all wheels, represents a maximum in the Exploitation of humans represents: but it presupposes those for whose reason this exploitation sense has. Otherwise, it would in fact simply be the overall reduction Werth-Reduction of the type human, — a decline phenomenon in the biggest style.

[...] [W] As I fight, is he economic Optimism: as if with the growing expenses Aller The benefits of all should also necessarily grow. The opposite seems to me to be the case: Everyone's expenses add up to a total loss: the human being becomes lesser: — so that you no longer know what this tremendous process was for in the first place. One for what? one new “What for! “— that is what humanity needs...24

In line with the idea of a — hoped-for — transformation of levelling into a new aristocracy, which has also been repeatedly discussed in the published work25 Although Nietzsche now adheres to his earlier critique of maschization, he also hopes that she will at the same time give birth to a new class of “supermen,” who will dominate the “army” of the machine of completely subjugated slaves. In antichrist He clearly states this political 'utopia' and explains it naturalistically: “That you are a public benefit, a wheel, a function, there is also a determination of nature: not the society, the species luck, which the vast majority are only capable of, turn them into intelligent machines.”26.

Is there already in Human, all-too-human aphorisms in which submission to the machine is described not apologetically, but also not critically, but purely descriptively as a “pedagogy,”27 Is he now increasingly going about recommending this subordination, even in the case of scholars, as a healing method against resentment28 and sees the early scene of the civilizational formation of humanity in the machinization of large parts of humanity by a small “caste” of brutal “predator people.”29

III. The Genius as an Apparatus?

But Nietzsche's fascination for machines does not stop there. Although he speaks himself in the Happy science against understanding the entirety of being as a machine, but not because this would mean devaluation or reification, on the contrary: “Let us beware of believing that the universe is a machine; it is certainly not based on a goal, we honor it far too much with the word 'machine'”30. Nietzsche, on the other hand, describes the human intellect completely uncritically as a machine in the same book31 And in the same way, human soul life as a whole should now be understood as a machine32. This applies, of all things, to the “genius”, which has been glorified since early work as the epitome of the highest authentic selfhood, which Nietzsche used from Morgenröthe compare with a machine over and over again.33 He speaks in the Götzen-Dämmerung, with none other than Julius Caesar as an example, even of “that subtle machine working under extreme pressure that is called genius.”34 and in a late estate fragment of him as the “most sublime machine [s] that exists”35.

The modern “rape of nature with the help of machines and the so harmless technical and engineering ingenuity”36 now celebrates Nietzsche as “power and sense of power [...] [,] hubris and godlessness” (ibid.) and therefore as an antithesis to modern decadence.37 An estate fragment from 1887 even states:

The task is to <zu>make people as usable as possible and to get them closer to the infallible machine as far as possible: for this purpose, he must work with Machine virtues be equipped (— he must learn to perceive the states in which he works in a machine-usable manner as the most valuable: it is necessary that the others be stripped as far as possible, as dangerous and disgusted as possible...)

Here is the first stumbling block boredom, the uniformity, which involves all mechanical activities. This Learning to endure and not just endure, learning to see boredom played around by a higher stimulus [.] [...] Such an existence requires philosophical justification and transfiguration more than any other: the pleasant Emotions must be discounted as lower rank by some infallible authority at all; the “duty itself,” perhaps even the pathos of reverence in regard to everything that is unpleasant — and this requirement as speaking beyond all usefulness, deliriousness, expediency, imperativity... The machinal form of existence as the highest most venerable form of existence, worshipping oneself.38

The revaluation is thus finally complete: It is no longer just a matter of creating a slave status of “machine people” with a sense of “advancement” of the species, which is confronted by a small group of “authentic” leaders, but all people should act equally as cogs of a large overall machine whose process is affirmed as an end in itself. In fact, only a distinction can be made between people who are cogs and those who form self-contained machines and are therefore destined to rule. Self-development as machinization.

Nietzsche thus becomes a pioneer of cybernetic techno-fascism, as Ernst Jünger had already foreseen on the eve of the “seizure of power” as a possible alternative to liberal humanism39 and today in “avant-garde fascist” circles40 again In vogue is, but also the post-modernist transfiguration of “becoming a machine” as a supposed subversive practice, as promoted tirelessly by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. The utopia of the flexible person as a “cyborg”41. It is almost funny that both the critical and the affirmative use of the machine metaphor apply equally in Nietzsche's last writings and testifies to the conflict of his thinking and his subjective indecision.

If you combine this last turn in Nietzsche's thinking with the concept of “eternal return,” which finds its tangible counterpart in the endless circle of machinery,42 Even though Nietzsche himself does not attempt this parallel, this analysis reveals the deeper reason for Nietzsche's “waste”: The growing insight into the structural dynamics of modern societies made him (ver) doubt more and more the possibility of realizing their authenticity. Not least because — as his letters mentioned above testify, which are probably not by chance at the very beginning of his “return” from machine striker to admirer — he recognized that the machinization of the world is not just an external skill, but an internal event from which one is subjectively unable to escape. Authenticity could then only be realized as a continuous fight against oneself. Dissatisfied with this, Nietzsche is now striving to radically affirm the machinization of the world mythologized as the “eternal return.” An affirmation which, however, like the talk of “hell machine” in Ecce homo underlines that it could only be successful at the price of complete self-abandonment, since its essence — as early Nietzsche recognized so clearly — is a misanthropic process which forces people to affirm something that, other than delusional, cannot be affirmed.

The obvious way out would be precisely to take on this fight against internal and external machinization — both in the sense of individual heroism and in the sense of political “machine-storming” — and to endure the internal conflict that the modern world of life imposes on people. But this is precisely where Nietzsche fails; he — contrary to what he himself called for — cannot maintain this tension, must “bridge” the “arc” of his ethics of authenticity43 with the help of his mythological constructions, which became ever more grotesque, ever more out of touch with reality in his late work. The real challenge that the ideal of authenticity poses to individuals is therefore to maintain one's own authenticity in a society dominated by inauthenticity without going crazy or succumbing to the conformist temptation of flexibility.

Literature

Benjamin, Walter: One way street. Frankfurt am Main 1955.

Ders. : Central Park. In: illuminations. Selected fonts. Frankfurt am Main 1977, pp. 230—250.

Haraway, Donna: A Cyborg Manifesto. In: Socialist Review 80 (1985), PP. 65—108.

Younger, Ernst: The worker. Domination and Form. Stuttgart 2022.

Stephen, Paul: Modernity as a culture of violence. Nietzsche as a critic of violence. In: Engagée. political-philosophical interventions 4 (2016), P. 20-23.

Footnotes

1: About the future of our educational institutions, Lecture V.

2: See, for example, ibid. and ibid., Speech I.

3: The benefits and disadvantages of history for life, paragraph 5. See also Schopenhauer as an educator, paragraph 3.

4: Subsequent fragments No. 1880 2 [62].

5: Subsequent fragments No. 1879 40 [4].

6: Human, all-too-human Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, Aph 220.

7: Subsequent fragments No. 1880 6 [104].

8: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 9 [162].

9: Beyond good and evil, Aph 6.

10: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, Aph 29.

11: Ibid., Aph 37.

12: Ecce homo, Why I'm so wise, paragraph 3.

13: Subsequent fragments No. 1873 29 [195].

14: Subsequent fragments No. 1876 23 [148].

15: Human, all-too-human Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, Aph 220.

16: Cf. Ibid., aph. 280.

17: Human, all-too-human, Vol. I, Aph. 585.

18: In this phase, Nietzsche even decisively expresses understanding for the workers' displeasure and recommends to them his ethics of authenticity as a way out of the dilemma “either a slave of the state or the slave of an overthrow party becomes must“(Morgenröthe, Aph 206). During this time, such mind games brought him remarkably close to anarchism (see e.g. Morgenröthe, Aph 179).

19: Cf. Bf. to Carl von Gersdorff v. 8/5/1875, No. 443; Bf. to dens. v. 26.6.1875, No. 457; Bf. to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche v. 30.5.1879, No. 849; Bf. to Heinrich Köselitz v. 14/8/1881, No. 136; Bf. to Franz Overbeck v. 31/12/1882, No. 366; Bf. to Malwida von Meysenbug v. 1/2/1883, No. 371; Bf. to Heinrich Köselitz v. 19/11/1886, No. 776; Bf. to Franziska Nietzsche v. 5.3.1888, No. 1003 and Bf. to Franz Overbeck v. 4/7/1888, No. 1056. It turns out that Nietzsche does not write these letters to “anyone,” but to his most intimate “small circle.” Nietzsche wrote to Overbeck on 14/11/1886: “The antinomy My current situation and form of existence now lies in the fact that everything that I as philosophus radicalis Nöthig Have — freedom from work, wife, child, society, fatherland, faith, etc., etc. I as many deprivations I feel that I am happily a living being and not just an analytical machine and an objectifying device” (No 775). A letter to Heinrich Romundt dated 15/4/1876 is also remarkable, which states: “I never know where I am actually more ill once I am ill, whether as a machine or as a machinist” (No 521).

20: Cf. Aph 86.

21: Cf. Subsequent fragments No. 1876 21 [11].

22: Cf. Human, all-too-human Vol. I, Aph 261.

23: Subsequent fragments No. 1884 25 [136].

24: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 10 [17].

25: See e.g. Beyond good and evil, Aph 242.

26: Paragraph 57.

27: Cf. Vol. I, Aph. 593 and Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, 218.

28: Cf. Subsequent fragments 1881 11 [31] and On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 18.

29: Cf. ibid., para. II, 17.

30: Aph 109.

31: Cf. Aph 6 and Paragraph 327.

32: Cf. Subsequent fragments No. 1885 2 [113] and The Antichrist, paragraph 14.

33: Cf. Morgenröthe, Aph 538; Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, Aph 8 and The Wagner Case, paragraph 5.

34: rambles, Aph 31.

35: Subsequent fragments No. 1888 14 [133].

36: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 9.

37: This passage is one of the most ambiguous in Nietzsche's work. At first glance, it makes sense to regard them as a critique of modern science and technology (see also my own essay on this subject Modernity as a Culture of Violence). But the late Nietzsche does not use “power” and even “rape” in any critical sense at all, as he keeps in the genealogy Clearly stated elsewhere:”[A] n yourself Of course, injuring, raping, exploiting, destroying cannot be anything “wrong”, insofar as life essential, namely hurtful, raping, exploitative, destructive in its basic functions and cannot be thought of at all without this character” (para. II, 11). And in the passage itself, it says: “[S] elbst still measured with the measures of the ancient Greeks, our entire modern being, insofar as it is not weakness but power and sense of power, looks like pure hubris and godlessness.” If one assumes that Nietzsche still refers positively to the “ancient Greeks” and their ethics of “measure,” this sentence should be read critically — but it is also obvious to understand it as meaning that in the described aspects of modernity, Nietzsche sees just the opposite of the “masterly moral” features of modernity that oppose their general nihilism. What objection should the declared “Antichrist” have against “ungodliness”?

38: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 10 [11].

39: Cf. The worker.

40: Just think of the corresponding visions of billionaires Elon Musk and Peter Thiel.

41: See, for example, Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto.

42: Walter Benjamin already recognized this connection between “eternal return” and the cyclicity of the capitalist economy (cf. One way street, P. 63 & Central Park, PP. 241—246).

43: Cf. Beyond good and evil, Preface.