#

Critique of Morality

From Denier to Conspiracy Theory to Ghosting

Nietzsche and the Social Upheavals Caused by Today's Widespread Resentment

From Denier to Conspiracy Theory to Ghosting

Nietzsche and the Social Upheavals Caused by Today's Widespread resentment

After Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann has already dealt with Nietzsche's concept of resentment in two articles on this blog (here and there), he now addresses the question of how it can be applied to the current social situation.

His thesis: The current political landscape is characterized by many divisions based on resentment. They are due to the weaknesses of their own arguments. This is how critics are defamed as “corona” or “climate deniers.” The objections are often branded as conspiracy theories. You can't ask 'Cui bono?' anymore. Or you break off contact without comment to protect yourself. This is not only in line with Nietzsche's understanding of resentment in many places, precisely because he himself is not free from it, but is looking for ways out of it.

“What is the topicality of Nietzsche's analysis and critique of 'resentment'?“ is also the question of this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing, in which you can once again win up to 750 Swiss francs. The closing date for entries is August 25. The complete tender text can be found here.

If you'd rather listen to the article, you can find an audiovisual version on the Halcyonic Association YouTube channel, read by the author himself (link) and a listening-online version on Soundcloud (link).

Nietzsche's Techniques of Philosophizing

With Side Views of Wittgenstein and Heidegger

Nietzsche's Techniques of Philosophizing

With Side Views of Wittgenstein and Heidegger

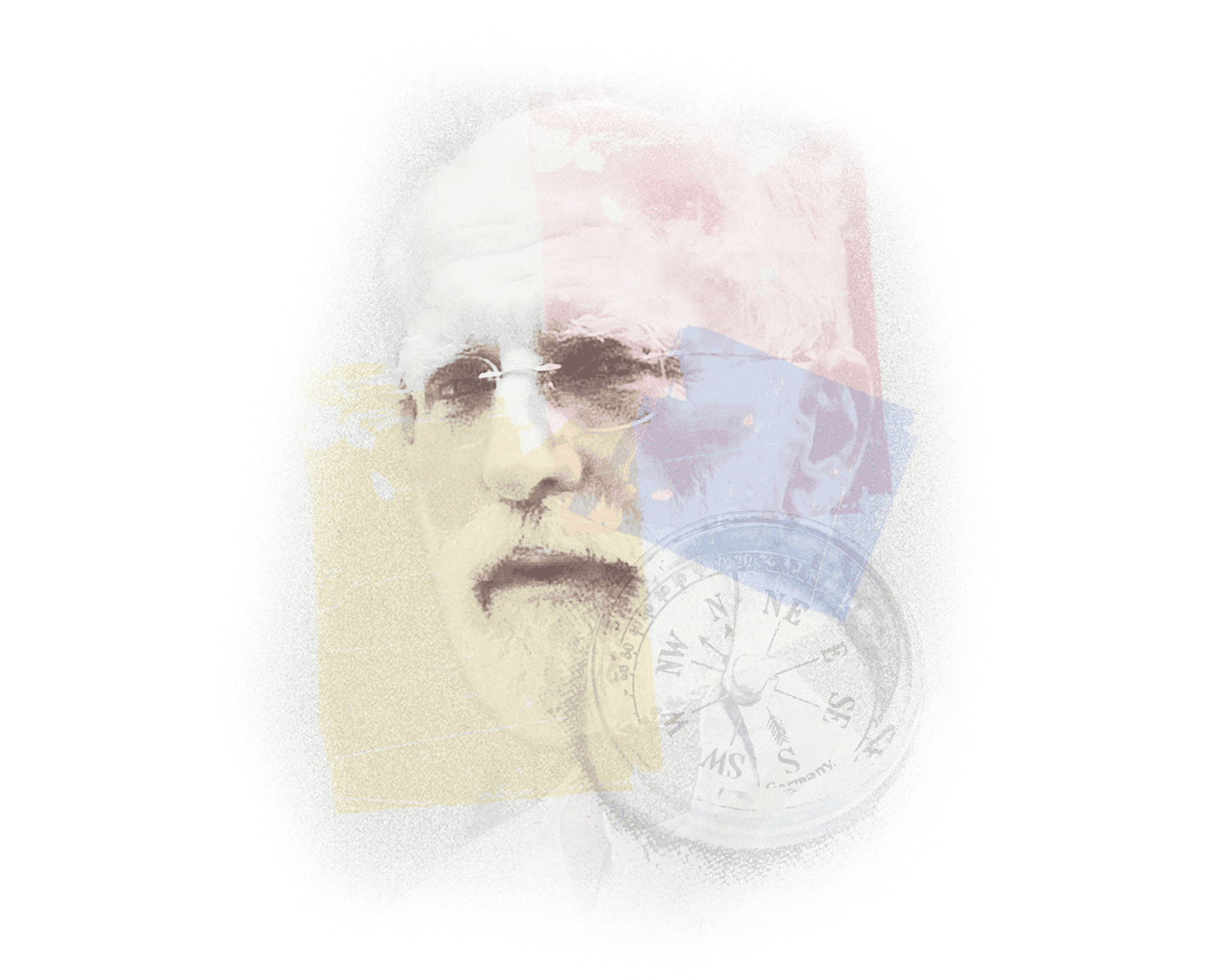

An integral part of the annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society is the “Lectio Nietzscheana Naumburgensis”, at which a particularly deserving researcher once again talks in detail about the topic of the congress on the last day and concludes succinctly. Last time, this special honor was bestowed on Werner Stegmaier, the long-time editor of the important trade journal Nietzsche studies and author of numerous groundbreaking monographs on Nietzsche's philosophy. The theme of the conference, which took place from 16 to 19 October, was “Nietzsche's Technologies” (Emma Schunack reported).

Thankfully, Werner Stegmaier allowed us to publish this presentation in full length. In it, he addresses the topic of the Congress from an unexpected perspective. This is not about what is commonly understood as “technologies” — machines, cyborgs, or automata — but about Nietzsche's thinking and rhetorical techniques. What methods did Nietzsche use to write in such a way that his work to this day not only convinces but also inspires new generations of readers? And what is to be said of them? He compares Nietzsche's techniques with those of two other important modernist thinkers, Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). In his opinion, all three philosophers say goodbye to the classical techniques of conceptual philosophizing founded in antiquity and explore radically new ones in order to try out a new form of philosophizing in the age of “nihilism.” A monotonous, metaphysical understanding of rationality is replaced by plural, perspective thinking, which must necessarily use completely different techniques. The article creates a fundamentally new framework for understanding Nietzsche's thinking and philosophical context.

Übermensch Hustling

Nietzsche Between Silicon Valley and New Right

Übermensch Hustling

Nietzsche Between Silicon Valley and New Right

This essay, which we awarded first place in this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing (link), examines Nietzsche's question of the “barbarians” in a contemporary context and analyses how his philosophy is being politically exploited today. Against this background, the text shows how hustle culture, platform capitalism and neo-reactionary ideologies have been economizing the ”will to power“ and have become a new form of subtle barbarism: an internal decomposition of cultural depth through market logic, technocratic myths, and performative nihilism. Nietzsche's thinking, however, can be used precisely to describe these tendencies in their genealogy, to unmask their immanent nihilism, and to present an (over-)humane alternative to them.

Female Barbarians — When Women Become a Threat

Female Barbarians — When Women Become a Threat

In today's world, which wants to call itself modern and equal, old patterns continue to have an effect — rivalry instead of solidarity, adaptation instead of departure. The essay provocatively asks: Where are the barbarians of the 21st century? It shows the emergence of a new female force — a woman who does not destroy but refuses, who evades old roles and gains creative power from pain. Through examples from reality and literature, the text attempts to show that true change does not start in obedience but in bold “no” — and that solidarity among women could be the real revolution.

We awarded this text second place in this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing (link).

If you'd rather listen to it, you'll also find it read by Caroline Will on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy's YouTube channel (link) or on Soundcloud (link).

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche‘s Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche's Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Last week, Emma Schunack reported on this year's annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society on the topic Nietzsche's technologies (link). In addition, in his article this week, Paul Stephan explores how Nietzsche uses the machine as a metaphor. The findings of his philological deep drilling through Nietzsche's writings: While in his early writings he builds on Romantic machine criticism and describes the machine as a threat to humanity and authenticity, from 1875, initially in his letters, a surprising turn takes place. Even though Nietzsche still occasionally builds on the old opposition of man and machine, he now initially describes himself as a machine and finally even advocates a fusion up to the identification of subject and apparatus, thinks becoming oneself as becoming a machine. This is due to Nietzsche's gradual general departure from the humanist ideals of his early and middle creative period and the increasing “obscuration” of his thinking — not least the discovery of the idea of “eternal return.” A critique of the capitalist social machine becomes its radical affirmation — amor fati as amor machinae.

Nietzsche and Cyborgs

The International Nietzsche Congress 2025

Nietzsche and Cyborgs

The International Nietzsche Congress 2025

Under the topic Nietzsche's technologies international visitors were once again invited to the Nietzsche Society conference in Naumburg an der Saale this year. In the period from October 16 to 19, in addition to various lectures, a film screening and a concert, there was also an art exhibition to visit. Our author Emma Schunack was there and reports on her impressions. Her question: How can Nietzsche's technologies find expression in the technological age?

Editorial note: The conference report does not mention the important “Lectio Nietzscheana Naumburgensis,” with which Werner Stegmaier rounded off the conference on Sunday morning and took up the topic of the conference again in a completely different way by asking about Nietzsche's own “philosophizing techniques.” We have now published this important talk in full length with the kind permission of the author (link).

The Barbarians of the 21st Century

Narcissism, Apocalypse, and the Absence of Other

The Barbarians of the 21st Century

Narcissism, Apocalypse, and the Absence of Other

The diagnosis of our time: not heroic barbarians, but selfie warriors. This essay, which won the second place at this year's Kingfisher Award (link), explores Nietzsche's vision of the”stronger type”1 and shows how it is turned into its opposite in a narcissistic culture — apocalypse as a pose, the Other as a blind spot. But instead of the big break, another option opens up: a “barbaric ethic” of refusal, of ambivalence, of relationship. Who are the true barbarians of the 21st century — and do we need them anyway?

Nietzsche and the Philosophy of Orientation

In Conversation with Werner Stegmaier

Nietzsche and the Philosophy of Orientation

In Conversation with Werner Stegmaier

On the 125th anniversary of Nietzsche's death on August 25, we spoke with two of the most internationally recognized Nietzsche experts, Andreas Urs Sommer and Werner Stegmaier. While the conversation with Sommer (link) focused primarily on Nietzsche's life, we spoke with the latter about his thinking, its topicality and Stegmaier's own “philosophy of orientation.” What are Nietzsche's central insights? And how do they help us to find our way in the present time? What does his concept of “nihilism” mean? And what are the political implications of his philosophy?

In Dialogue with Nietzsche

AI, Philosophy and the Search for Authenticity

In Dialogue with Nietzsche

AI, Philosophy and the Search for Authenticity

A year ago, our author Paul Stephan conducted a small “dialogue” on the 124th anniversary of Nietzsche's death with ChatGPT to see to what extent the much-hyped program is suitable for discussing complex philosophical questions (link). Paul Stephan now fed it, for the 125th, with some of the same, partly changed questions. Has it improved? Judge for yourself.

What follows, is a very abbreviated excerpt of the conversation. The full commented “dialogue” can be found here [link].

The article image was created by ChatGPT itself when asked to generate a picture of this chat. The other pictures were created again by the software DeepAI based on the prompt: “A picture of Friedrich Nietzsche with a quote by him.”

Read also our author's philosophical commentary on this “talk” (Link).

Note: A lot of the weirdness of this encounter is lost in the subsequent automated translation. Thus, it's also a part of this experiment on the “philosophical capabilities” of AI. Check the original if you want to get everything.

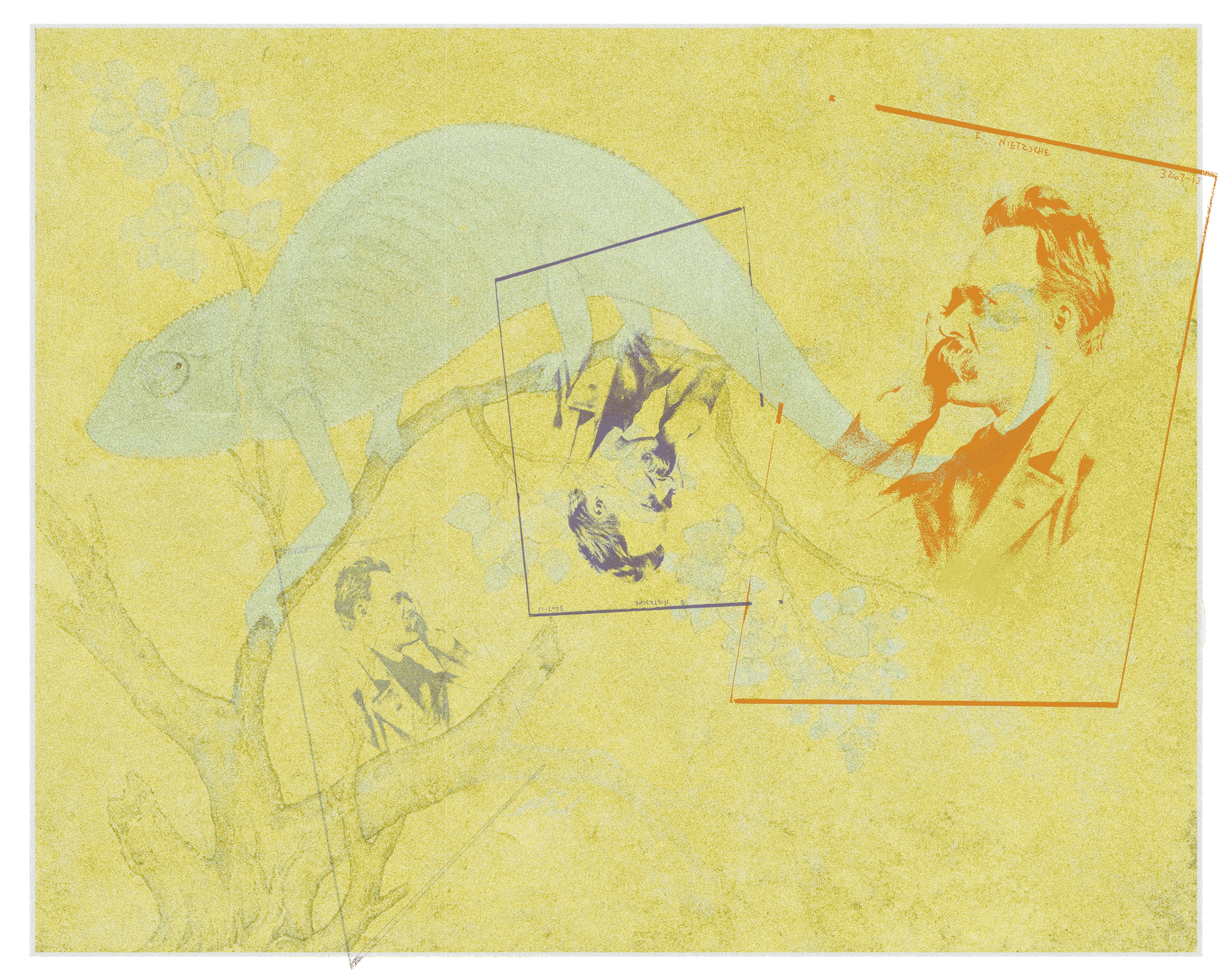

Chameleon Nietzsche

The Failure of Nietzschean Materialism

Chameleon Nietzsche

The Failure of Nietzschean Materialism

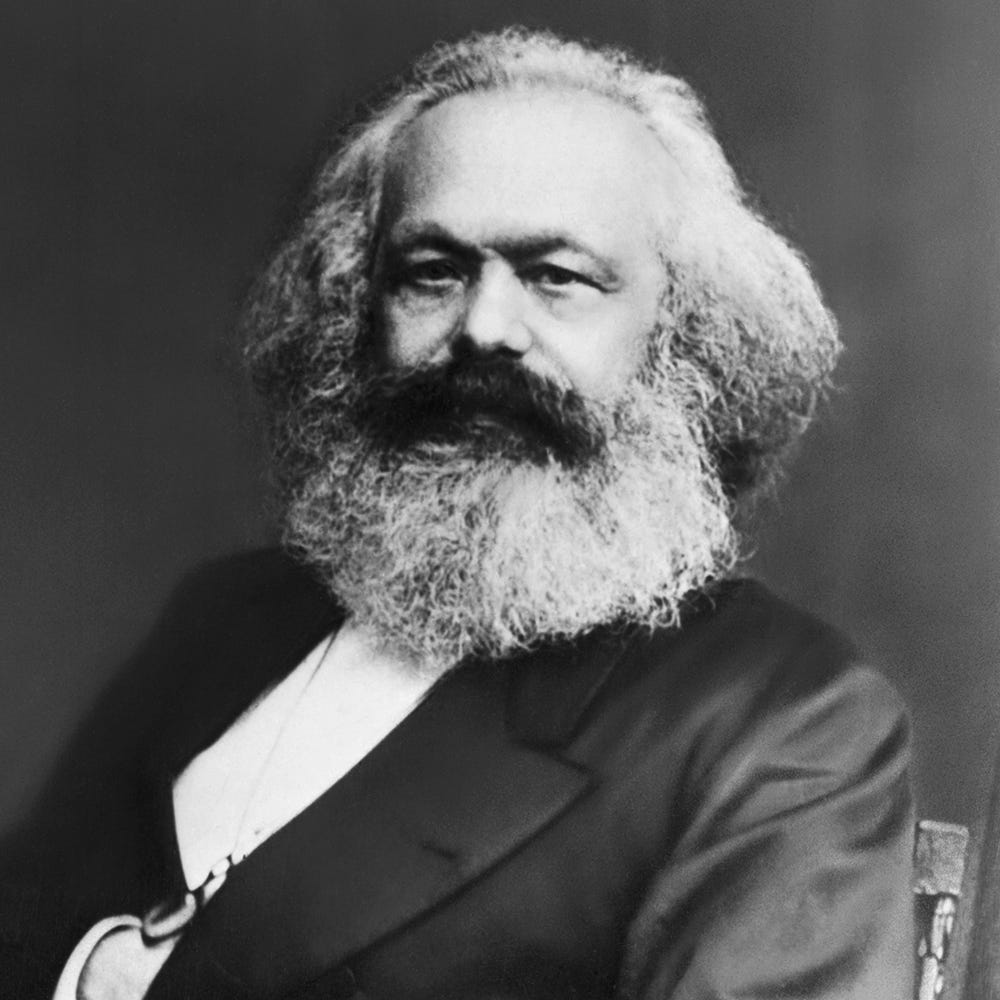

The connection between Marx(ism) and Nietzsche(anism) has repeatedly been a topic on our blog. To what extent can the ideas of arguably the most important theorist on the left and the philosophical chameleon, who was an avowed anti-socialist and anti-feminist and inspired Goebbels and Mussolini, among others, be meaningfully combined. While there have been repeated attempts at left-wing Nietzscheanism, Estella Walter's conclusion in this controversial thesis article is skeptical: The contrast between “historical-dialectical materialism” and Nietzsche's idea of will to power is too irreconcilable. Beyond his time diagnosis, his thinking only provides little emancipatory content.

Mythomaniacs in Lean Years

About Klaus Kinski and Werner Herzog

Mythomaniacs in Lean Years

Über Klaus Kinski und Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog (born 1942), described as a “mythomaniac” by Linus Wörffel, and Klaus Kinski (1926—1991) are among the leading figures of post-war German cinema. In the 70s and 80s, the filmmaker and the actor shot five feature films that are among the classics of the medium's history. They are hymns to tragic heroism, in which the spirit of Nietzsche can easily be recognized. From “Build Your Cities on Vesuvius! “will “Build opera houses in the rainforest! ”.

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Strangers seem creepy to many. They immediately fear that these strangers will harm them. Many decent earners think that recipients of citizen benefits are lazy and therefore do not allow them to receive government support. To many educated people, illiterate people appear rude and simple-minded, with whom they therefore want as little as possible nothing to do with, whom they do not trust. Religious people are often afraid of atheists, who in turn are afraid of contact with religion. What you don't know often appears to be dangerous and you prematurely discount that. Such prejudices lead to rejection, which often solidifies to such an extent that counterarguments are no longer even heard. This is resentment that has existed for a long time, but which today makes consensus almost impossible in many political and social debates. This can degenerate into hate and contempt and then into violence whether between rich and poor, right and left, machos and feminists, abortion opponents and abortion advocates, vegetarians and meat-eaters. When one side prevails, it imposes its values on the other, and the resentment even becomes creative. In any case, it prevents you from making an effort to understand the other person. For Nietzsche, resentment has been driving the dispute over what is morally necessary for a long time.

“Resentment” is one of the key terms of Nietzsche's late work. The philosopher is referring to an internalized and solidified affect of revenge, which leads to the development of an overall negative approach to the world. Especially in On the genealogy of morality Nietzsche is trying to show that the entire European culture since the rise of Christianity has been based on this affect. Judaism and Christianity, in their hatred of aristocrats, propagated an ethics of the weak — in this act, resentment became creative. With a new creative ethic, Nietzsche now wants to contribute to a renewed revaluation of values in order to return to a life-affirming aristocratic ethic of the “strong.” In this article, Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann introduces Nietzsche's reflections on resentment and works out what makes the accusation of mutual resentment so popular to this day.

Considering Artificial Intelligence with Nietzsche

On the Critique of Current AI Debates

Considering Artificial Intelligence with Nietzsche

On the Critique of Current AI Debates

.jpg)

Transhumanists believe that artificial intelligence is used to capture the real world. It wasn't just Nietzsche who presented this as nonsense. Moral programs are entered into the AI. With Nietzsche, this prolongs hostile morality. And Nietzsche would have already questioned the fact that AI helps people. Instead, people must submit to AI. With Nietzsche, they can evade their power.

“Choose the right time to die!”

Nietzsche's Ethics of “Free Death” in the Context of Current Debates About Suicide

A Conversation with Filmmaker Lou Wildemann

“Choose the right time to die!”

Nietzsche's Ethics of “Free Death” in the Context of Current Debates About Suicide. A Conversation with Filmmaker Lou Wildemann

Lou Wildemann is a cultural scientist and filmmaker from Leipzig. your current feature film project, MALA, deals with the suicide of a young resident of Nietzsche City. Paul Stephan discussed this provocative project and the topic of suicide in general with her: Why is it still taboo today? Should we talk more about this? What role can Nietzsche's reflections, who repeatedly thought about this topic, play in this? What does suicide mean in an increasingly violent neoliberal society?

Traveling with Nietzsche through Southeast Asia III

Thailand

Traveling with Nietzsche through Southeast Asia III

Thailand

Our author Natalie Schulte traveled by bicycle for nine months Vietnam, Kampuchea, Thailand and malaysia. In her penultimate contribution to the series ”Hikes with Nietzsche“ she muses on encounters with wild animals that she met or could have met on her journey. It is hardly surprising that this includes considerations about the importance of animals, as they occur in Nietzsche's philosophy.

“Music, your advocate”

Nietzsche and the Liberating Power of Melody

“Music, your advocate”

Nietzsche and the Liberating Power of Melody

After Christian Saehrendt took a primarily biographical look at Nietzsche's relationship to music on this blog in June last year (link), Paul Stephan focuses in this article on Nietzsche's content statements about music and comes to a somewhat different conclusion: For Nietzsche, music has a liberating power through its subjectivating power. It affirms our sense of self and inspires us to resist repressive norms and morals. However, not all music can do that. With late Nietzsche, this is no longer Richard Wagner's opera, but Georges Bizet's opera carmen. Our author recognizes a similar attitude in Sartre's novel The disgust and in black popular music, which is not about comfort or grief, but affirmation and overcoming.

Discourse, Power and Delusion

Michel Foucault's Nietzsche Interpretation Revisited

Discourse, Power and Delusion

Michel Foucault's Nietzsche Interpretation Revisited

The humanities scene recently experienced a minor sensation: In the estate of Michel Foucault (1926—1984), one of the most important representatives of post-structuralism, its editors came across an elaborate book manuscript with the title Le discours philosophique, on which the avowed Nietzschean had worked in 1966. It was published in German by Suhrkamp in 2024. Nietzsche plays a decisive role in this comprehensive analysis of philosophical discourse since Descartes. Paul Stephan takes this event as an opportunity to take a closer look at the most influential Nietzsche interpretation of the 20th century to date.

The Educator’s Mark

Schopenhauer's Omnipresence in Nietzsche's Philosophy II

The Educator’s Mark

Schopenhauer's Omnipresence in Nietzsche's Philosophy II

After explaining in the first part of this article (link) how Nietzsche transformed from an admirer of Schopenhauer to a critic in the course of the 1870s, Tom Bildstein now examines in more detail how the mature Nietzsche sought to overcome Schopenhauer‘s pessimism and counter it with a “life-affirming” philosophy. Schopenhauer‘s “will to life,” which the misanthrope would like to see ascetically denied, is to give way to the “will to power” as the fundamental principle of all life, which cannot be denied without contradiction.

Age-Old Rage

The birth of Modernity out of the Spirit of Resentment

Age-Old Rage

The birth of Modernity out of the Spirit of Resentment

“Resentment” is one of the guiding concepts of Nietzsche's philosophy and perhaps even its most effective. In his new book The cold rage. Resentment theory and practice (Marburg 2024, Büchner-Verlag), Jürgen Grosse argues that since the 18th century, more or less all political or social movements have been those of resentment. Our main author Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann has read it and presents major theses below.

“Peace Surrounds Me”

An Unusual Christmas Message

“Peace Surrounds Me”

An Unusual Christmas Message

In our last article before the break at the turn of the year, Paul Stephan explores a Close reading A remarkable aphorism of Nietzsche, in which he expresses himself with the famous Christmas blessing “Glory be to God in height and peace on earth and to people! “discusses. As when unwrapping a gift that has been covered several times, he tries to reveal the different layers of meaning in this text in order to make Nietzsche's exact positioning clearly stand out. The reader may decide for himself whether you end up holding a glowing truth in your hand or the box remains empty. In any case, we wish all our readers with Nietzsche: “Peace on earth and good pleasure for each other! ”

“The Most Noble Adversary”

Daniel Tutt and Henry Holland in Dialogue

“The Most Noble Adversary”

Daniel Tutt and Henry Holland in Dialogue

After two previous contributions to Nietzsche in the Anglosphere For this blog, Henry Holland interviewed American thinker Daniel Tutt about his perspective on Nietzsche as the most important antagonist of the left. The discussion included Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panthers in the 1970s, and what his “parasitic” way of reading Nietzsche prompted him to read. An unedited and unabridged version of this interview, in original English, can be heard and watched on Tutt's YouTube channel (link).

A Day in the Life of Nietzsche's Future

Report on the Conference Nietzsche's Futures in Weimar

A Day in the Life of Nietzsche's Future

Report on the Conference Nietzsche's Futures in Weimar

From October 7 to 11, 2024, the event organized by the Klassik Stiftung Weimar took place in Weimar Nietzsche's futures. Global Conference on the Futures of Nietzsche instead of. Our regular author Paul Stephan was on site on the first day and gives an insight into the current state of academic discussions about Nietzsche. His question: What is the future of Nietzsche academic research when viewed from the perspective of Nietzsche's own radical understanding of the future?

“A Gods’ Table for Divine Dice Throws and Dice Players”

Nietzsche's Superman Visits the Start-Up Scene

“A Gods’ Table for Divine Dice Throws and Dice Players”

Nietzsche's Superman Visits the Start-Up Scene

Nietzsche's superman is dead. Hardly anyone can do anything with this obscure idea anymore. You'd think so. And yet, in the current startup environment, you encounter numerous set pieces from Zarathustra's promise. What is it all about? — On the occasion of Nietzsche's 180th birthday, Natalie Schulte dedicates herself to this peculiar continuation of one of the philosopher's best-known concepts. A plea for taking a closer look at Nietzsche's idea despite its past and present misinterpretations.

Editor's note: We have translated longer English quotations into German in the footnotes ourselves.

Boomers, Zoomers, Millennials

How Do the Respective Perspectives on Nietzsche Differ?

Boomers, Zoomers, Millennials

How Do the Respective Perspectives on Nietzsche Differ?

This time in confidential Du, Paul Stephan talked to Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann, our oldest parent author, and our youngest regular author, Estella Walter, about our different generational experiences and about what is actually to be thought of the fashionable discourse about the different “generations.” We talked about post-structuralism, the ecological issue and the diversity of possible connections to Nietzsche.

Society versus Self-Becoming

A Dialogue about Nietzsche, Authenticity and the Challenges of Modernity

Society versus Self-Becoming

A Dialogue about Nietzsche, Authenticity and the Challenges of Modernity

To commemorate the 124th anniversary of Nietzsche’s death, Paul Stephan conversed with a rather particular kind of Nietzsche expert—the now near ubiquitous ChatGPT. Their discussion circled around questions of why Nietzsche matters today and his concept of authenticity. During the course of the conversation, Stephan switched from asking to fielding questions, and elaborated briefly on how his own doctoral dissertation also focuses on authenticity. As Stephan’s experiment aimed at probing deep into the program’s capabilities, and because brevity is not ChatGPT’s strongest asset, we present here an abridged version of the conversation. Readers of German who wish to delve deeper can view the unabridged and annotated PDF that’s available as a download (link). Watch out for Stephan’s critical reflections on this truly remarkable dialogue within the next few days (link).

The pictures accompanying the interview were created with DeepAI software, which was asked to produce “A picture of Friedrich Nietzsche with a quote by him.”

Nietzsche’s Monkey, Nietzsche’s Varlet

The Oswald Spengler Case

Nietzsche’s Monkey, Nietzsche’s Varlet

The Oswald Spengler Case

In the following article, Christian Saehrendt gives a brief insight into the work of one of the most controversial but also most influential Nietzsche interpreters of the 20th century: the German philosopher Oswald Spengler (1880—1936). The author of The fall of the West (1917/22) is considered one of the most important representatives of the “Conservative Revolution,” an intellectual movement that was significantly involved in the cultural destabilization of the Weimar Republic before 1933. Largely forgotten in Germany, it continues to be eagerly received in a global context, such as in Russia.

Whistling in the Woods and Screaming for Love

Nietzsche's Echo in the Heavy Metal Music Scene

Whistling in the Woods and Screaming for Love

Nietzsche's Echo in the Heavy Metal Music Scene

Like hardly any other philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche has left his mark on popular culture — less in the pleasing mainstream entertainment, but more in subcultures and in artistic positions that are considered “edgy” and “dark.” In this “underworld,” Nietzsche's aphorisms, catchphrases, slogans and invectives are widely used — for example in the musical genres of heavy metal, hardcore and punk focused on social and aesthetic provocation. What is the reason for that?

Nietzsche doesn’t Mean: Nietzsche Lives

Nietzsche doesn’t Mean: Nietzsche Lives

In the last part of the series “What does Nietzsche mean to me? “, in which our regular authors briefly presented their respective understanding of Nietzsche in recent weeks, Estella Walter tells of 'her' Nietzsche as a critic of any totality in the name of the nameless reality of becoming.

The Enlightenment’s Twilight

Nietzsche's Truth of Semblance II

The Enlightenment’s Twilight

Nietzsche's Truth of Semblance II

After Michael Meyer-Albert in the first part of his text Telling the sad story of the self-doubt of the Enlightenment, he now reports on Nietzsche's “cheerful science” as an alternative.

Nietzsche’s Critique of Capitalist Alienation

Nietzsche’s Critique of Capitalist Alienation

In the penultimate part of the series “What does Nietzsche mean to me? “Lukas Meisner comes to a surprising result at first glance: Nietzsche and Marx both practice fundamental criticism of capitalism and Nietzsche can serve to Marx's To complement a critique of political economy with a no less radical critique of moral economy.

“Je suis Nietzsche!”

A Dialogue about Bataille, Freedom, the Economy of waste, Ecology and War

“Je suis Nietzsche!”

A Dialogue about Bataille, Freedom, the Economy of waste, Ecology and War

Paul Stephan talked to Jenny Kellner and Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann about the interpretation of one of the most important Nietzsche interpreters of the 20th century: Georges Bataille (1897—1962). The French writer, sociologist and philosopher defended the ambiguity of Nietzsche's philosophy against its National Socialist appropriation and thus became a central source of postmodernism. Based on Dionysian mythology, he wanted to develop a new concept of sovereignty that transcends the traditional understanding of responsible subjectivity, and criticized modern capitalist rationality in the name of an “economy of waste.” With all this, he provides important impulses for a better understanding of our present tense.

Deciding to Serve Life

An Essay on the Meaning of Nietzsche's Philosophy

Deciding to Serve Life

An Essay on the Meaning of Nietzsche's Philosophy

Nietzsche is generally regarded as a literary philosopher whose aphoristic nihilisms not only conjure up the death of God, but who also reinforced the dark sides of German history as a posthumous master thinker. In contrast, the following text would like to be part of the series What does Nietzsche mean to me? invite you to learn to read Nietzsche anew as the discoverer of the all-too-unknown philosophical continent of Mediterranean existentialism.

Menke Fascinates.

Is Liberation Fascination?

Menke Fascinates.

Is Liberation Fascination?

In his recently published study Theory of Liberation [Theorie der Befreiung]Frankfurt philosopher Christoph Menke describes liberation as “fascination,” as pleasurable desubjectization and dedication. He refers decisively to Nietzsche — but for him, “fascination” means bewitching, entanglement in lack of freedom and resentment. Can the mystical power of fascination really set us free — or is it not rather Nietzsche's right and liberation means above all self-empowerment and autonomy, whereas the fascinated sacrifice means submission, not least to a fascist leader?