Nietzsche and the Philosophy of Orientation

In Conversation with Werner Stegmaier

Nietzsche and the Philosophy of Orientation

In Conversation with Werner Stegmaier

On the 125th anniversary of Nietzsche's death on August 25, we spoke with two of the most internationally recognized Nietzsche experts, Andreas Urs Sommer and Werner Stegmaier. While the conversation with Sommer (link) focused primarily on Nietzsche's life, we spoke with the latter about his thinking, its topicality and Stegmaier's own “philosophy of orientation.” What are Nietzsche's central insights? And how do they help us to find our way in the present time? What does his concept of “nihilism” mean? And what are the political implications of his philosophy?

I. Nietzsche and Nihilism

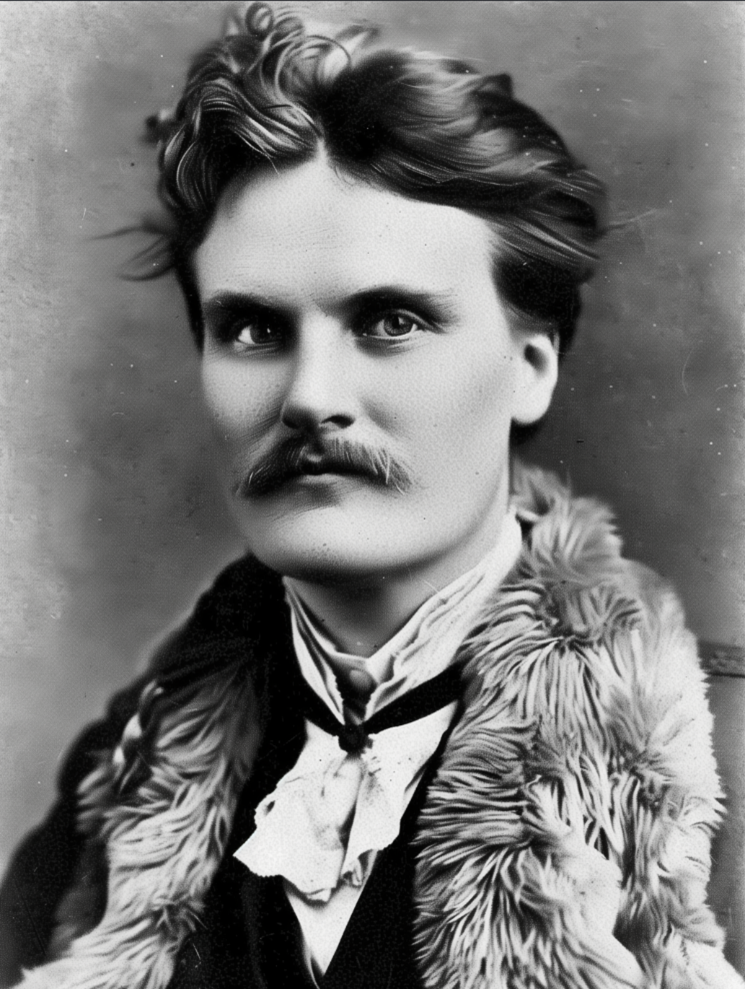

Paul Stephan: Dear Professor Stegmaier, it is probably no exaggeration to describe you as a luminary in Nietzsche philosophical research. In addition to countless essays, you have written in particular an extremely readable Junius introduction to Nietzsche's thinking, which can be translated into English free of charge here can download, as well as an extensive interpretation of the so important fifth book of Happy science (Nietzsche's liberation of philosophy, 2011), the study Orientation in nihilism. Luhmann meets Nietzsche (2016), a collection of essays available free of charge on the Internet entitled Europe in ghost war. Studies on Nietzsche (2018, link) and an interpretation of his estate (Nietzsche at work, 2022) — just to name the perhaps most important. There are also countless anthologies edited by you. Last but not least, you were the managing editor of the important trade journal for 18 years Nietzsche studies and the series of publications Monographs and texts on Nietzsche research. When you look back on all your years of “involvement” with Nietzsche, unless the word is an understatement: What does his central insight seem to you to be? What is the essential lesson that you can and should learn when reading Nietzsche's writings — which, as you yourself write in the introduction to your mentioned introduction to his thinking, are easy to read but difficult to understand?

Werner Stegmaier: Nietzsche's bravest and central insight was, it seems to me that nihilism, according to which it is nothing with the seemingly highest values and all absolute certainties, is a “normal state,” as he recently wrote over a long record of it with double underlining.1 There is also nothing to overcome, as Heidegger in particular said. According to Nietzsche, the nihilism of Christianity and metaphysics, which had nothing to do with the truly livable values, overcame themselves by cultivating a sense of truth with their ascetic ideal which finally turned against themselves and made them implausible. This insight has had a tremendous liberating effect. According to Nietzsche, in the “revaluation of all values,” which was now up to everyone to decide for themselves which values they wanted to uphold, and in philosophy, if you were brave enough to do so, you could start with everything anew, in content as well as in forms. We still live on it today.

PS: Nietzsche undoubtedly sees nihilism as a great opportunity, as a necessary stage of transition for a new culture. But not also as a danger, as a loss of orientation in a world that no longer has objective orientations to offer? I'm just thinking of Nietzsche's perhaps most famous aphorism, the 125. the Happy science.

WS: Yes, Nietzsche makes a “great person” — a crazy person in the former sense — scream out: “Where is God? I want to tell you! We killed him, — you and I! We're all his killers! “, but at the same time also ask him:

But how did we do it? How were we able to drink the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What did we do when we released this earth from its sun? Where is it heading now? Where are we heading? Away from all suns? Don't we keep falling? And backwards, sideways, forwards, to all sides? Is there still an up and a down? Are we not mistaken as if by infinite nothingness? Doesn't empty space breathe on us?

In spatial metaphors, this great person conjures up a new and complete disorientation in an infinite void in which you can no longer hold on to anything. At the beginning of Book V of Happy science, which Nietzsche added five years later, he takes up in his own name the “greatest recent event — that 'God is dead, '” clarifying “that faith in the Christian God has become implausible,” and paints what you ask for, a “long abundance and sequence of abort, destruction, fall, revolution,” which is now imminent with nihilism, “an atomization,” which is now imminent with nihilism, “an atomization Eclipses and eclipses whose parallels have probably never existed on Earth yet”2. A little later, in the famous Lenzerheide recording, in which he attempts to overview and organize his assessment of nihilism, he adds that there will be a “will to destroy” and “self-destruction,” with which the now clueless and disoriented would “breed their own executioners.”3 And with that, you could easily identify the Germans and the Russians as well as their leaders Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin. For Nietzsche, who might have foreseen something like this but of course could not foresee it, this was just a “crisis” that would “purify” and lead to fundamentally new social conditions. For philosophers like him, however, it would bring “a new kind of light, happiness, relief, exhilaration, encouragement, dawn that is difficult to describe.” There is a great “gratitude” in him that “the horizon is now clear again,” “every risk of the discerning person is allowed again” and “the sea, our Meer” lay there open again. For Nietzsche, philosophy did not stand above world events as mere theory, but was directly integrated into it, just as every orientation is integrated into it, because it always has a point of view in it and also influences it itself. Nietzsche believed that philosophy could set new goals and pave the way for world events, and his philosophy may have actually done so.

PS: What new goals and paths do you have in mind?

WS: Nietzsche set them as big as possible: Nihilism, he assumed, will free (European) humanity to higher development, release it from the shackles of the ascetic ideals of Christianity so that it can develop its real and strong opportunities anew. That does not mean, as some “transhumanists” now believe, that everyone should become superhumans.4 One should just not assume that humanity would have already achieved its goal if it fulfilled those ideals, and that the “last” person, now definitely established, could bask in his happiness. According to a famous Nietzsche phrase, the human being is “the Not yet identified thiers”5, which cannot help but develop much faster than other animals due to its extraordinary intellectual abilities. For Nietzsche, however, this can only happen in an evolutionary way, through constant interaction between individuals. Evolution produces an enormous wealth of variants for him, and for higher development it depends on the particularly “successful cases” (ibid.). They always remained exceptions, but they could hardly venture out as long as all, in accordance with the old “Equal before God” (ibid.), are as equal as possible in everything and should therefore definitely be equated. In this way, “the type of 'human' is recorded at a lower level” (ibid.) and the major problems that now arise, namely, first and foremost “create better conditions for the development of people, their nutrition, education, education, education, economic administration of the earth as a whole, weigh up and use the forces of people in general.”6, could not be tackled in this way in a promising way. Instead, “the completed original folk cultures” must7 overcome, “one that exceeds all previous degrees Knowledge of the conditions of culture as a scientific measure for ecumenical goals”8 are achieved that span the whole world, and first of all Europe, which Nietzsche still sees in a leading role here, unites and the Jew9 In doing so, their pioneering role is acknowledged. For “such a conscious overall government”10 The Earth needs “higher people” who, with superior orientation, could set new goals for the world as a whole. And Nietzsche may have had a mistaken world politician like Kaiser Wilhelm II, but not yet faced the worldwide environmental destruction caused by industrialization, the threat of nuclear world wars and the now explosive, extreme distribution of wealth with which we are confronted, among many other global problems. On the other hand, “[d] he older morality, in particular the Kant's, [which] [requires] actions from the individual, which are desired from all people” (ibid.), now as “a nice naive thing” (ibid.): “[A] l whether everyone would know without further ado in which course of action the whole of humanity is good, i.e. which actions are actually desirable” (ibid.). In such contexts, Nietzsche often used a language that was later contaminated by the Nazis, and intensified it aggressively the less people wanted to hear him. However, this should not obscure his vision.

II. Nietzsche's Politics

PS: I see a close connection to Marxism in this aspect of Nietzsche's philosophy. There is also a remarkable place in Ecce homo, where he summarizes his program as follows:

My task to prepare humanity for a moment of supreme self-reflection, a big noonWhere she looks back and looks out, where she emerges from the reign of chance and the priest and the question of why? , of what for? for the first time as a whole poses —, this task necessarily follows from the insight that humanity not It is on the right track of its own accord that she is absolutely not It is divinely ruled that, precisely under their most sacred values, the instinct of negation, corruption, the décadence instinct has acted seductively.11

Although you could even think of the UN. While the difference may be that Nietzsche does not exactly democratically design this “conscious overall government.” But perhaps that is simply realistic and such comprehensive social and cultural reforms must be initiated by small avant-gardes. Despite its claim, Marxism, in its practical implementation, was ironically closer to Nietzsche than to Marx in this respect; and the UN is also perceived by many as elitist and “aloof.” In view of the numerous fundamental human problems with which we are in fact currently confronted, do you think that we should build on this' elitist 'model of social transformation more openly? Or could a radical transformation also be made more democratic than Nietzsche suggests?

WS: In fact, the outstanding position from Ecce homo Describes once again in terms of Morgenröthe, to which it applies what Nietzsche later calls “nihilism”: the need for a complete reorientation of philosophy after the highest metaphysical Christian priestly values have proven to be fundamentally baseless. Humanity must now remember that it is not a higher power that sets its goals, but that it must set goals for itself if it does not want to wander around senselessly. Instead of “nihilism,” Nietzsche recently preferred the term “décadence”, which appeared in France — out of disappointment with the old meanings, one only sees decay, only negates. That continues to this day. But it was precisely metaphysics and Christianity that concealed the negative by setting the “higher” values against the values actually worth living in, which they denied or even disparaged them. Philosophers have often been up to now, Nietzsche adds in the same passage,”hid Priest.” They constructed “the salvation of the soul” from “contempt for the body” and its healthy ““egoism.” But there are now strong opposition movements. Nietzsche also speaks here, we must not conceal this, of the “degeneration of the whole, of humanity,” but without, like the Nazis, who of course gladly took up this, to combine it with biological racism; the Nazi ideology would have sharply rejected Nietzsche. Even in his time, he clearly recognized himself as an anti-nationalist, anti-socialist and anti-Semite.

Nietzsche barely noticed the Marxism of that time; he does not even mention the name Marx (and vice versa). If he had paid attention to Marx, he would probably have taken on a bold new goal for humanity, in the “fight against the morality of self-determination,” which he also led himself — this is how the aphorism quoted above ends. Both spoke of “alienation,” and both were able to draw on Ludwig Feuerbach, who saw alienation morality in Christianity: Everything good about people is projected onto God and God's Son; the bad remains with people themselves. But Marx saw in the development of (European) humanity, and Nietzsche would not have participated, a self-directed course predetermined by the production relations of the emerging industrial society, which would eventually lead to the revolution of the proletariat. For Nietzsche, this would only have been a different kind of external determination. He saw that when it comes to the major human problems mentioned above, that we spoke of, even in democracy, which he described as “unstoppable.”12 held, in all areas not without orientational leaders — not domineering and selfish autocrats. Elites may and must also develop over time, but this is certainly possible in democratic selection processes. “Elitist” has also become a fighting term; “elite,” also adopted from French in the 18th century, meant “selection of the best.” If they — in the aristocracy, in the military, in business and in banking — can form a caste, for example through targeted marriage policies, and take on permanent positions of power, they appear “detached.” But even that has clearly outlived itself; democracy has successfully resisted it.

Today, you no longer have to be descended from an elite caste — Nietzsche also played with this idea when he looked at the Indian “Manu Code of Law” with its humanly “noble values everywhere,” his “yes to life.”13 —, in order to give humanity new ideas for a prudent and far-sighted orientation for its future, and these ideas too must first prevail in a democratic process. In nihilism as a normal state is like an “experimental philosophy”14 An “experimental ethic” is also popular — over “long centuries”15 away. What works in it is then enshrined in norms, values and laws and, if that helps, revelations are also attributed so that we can stick to them for now, and this is where the 'priests' come into play again. On the other hand, according to Nietzsche, “[d] he most spiritual people find Strongest, [...] their happiness, in which Andre would find their downfall: in the labyrinth” (ibid.) — i.e. where others can no longer orient themselves —, “in harshness against themselves and others, in attempt; their pleasure is self-conquest: ascetism becomes nature, need, instinct” (ibid.) — we would say today, to a sense of orientation that they also share with others be able to mediate. Nietzsche also vaguely grants them other “rights” and “privileges” due to their higher “responsibility” — we would no longer go along with them today; at least legal privileges have been overtaken by the democratic procedures that have now been established. Ideas and people with ideas must remain competitive if they are to be successful. Effective governance, particularly in the major issues, which is now expected and demanded everywhere, has not become easier, but decisions can thus be more approved and enforced more sustainably.

III. The Philosophy of Orientation

PS: This is perhaps a good point to finally talk about your own thinking, which has been revolving around the concept of “orientation” for some time now. In 2008, you published the extensive work philosophy of orientation, and since then, numerous publications have been added to this concept. Since then, this idea has been so well received that even its own foundation, the Foundation for Philosophical Orientation, founded in 2019, can also be downloaded free of charge on its website (link), dedicated to popularizing and discussing this term. Would you like to outline what you are interested in and how you see Nietzsche as a pioneer of this new philosophy?

WS: Sure, I've already tried to explain Nietzsche's philosophies in terms of orientation. For him, as I said, nihilism meant an extremely profound and difficult to endure disorientation of the entire European-educated humanity as it lost faith in Christianity and metaphysics. As a result, everyone wanted to 'overcome' nihilism — and in doing so somehow return to the absolute certainties of the old type. I have always found Nietzsche's philosophizing liberating — towards a comprehensively new philosophical orientation in nihilism as a “normal state.” I saw more and more clearly that the terms of the great philosophical tradition were no longer suitable for such a reorientation. After thoroughly studying Kant, Hegel, Wittgenstein and Heidegger, I dedicated my dissertation to the basic concept of metaphysics, the concept of substance.16 It revealed that on the way from Aristotle via Descartes and Spinoza to Leibniz and Kant himself, “substance” loses the sense of a fixed and absolutely certain existence and becomes a mere category with the function of finding support in Heraclitic becoming, but a hold on time that shifts over time. I then called this “fluctuation” and wrote my doctoral thesis on Dilthey and Nietzsche, in whose work this fluctuation develops in different ways.17 With regard to the evolution of humans and then of humans in their history, we expect today that all concepts, including those of philosophy, are and must be constantly in flux if they are to move with the times. Nietzsche also pointed out this with his “The form is fluid, but the 'meaning' is even more...”18 constantly squeezed. Because of compilation The will to power, who had organized Nietzsche's rather biased sister very amicably after his death, Heidegger, on the other hand, stylized Nietzsche's philosophizing into a new metaphysics of the will to power, which drives all previous metaphysics to the extreme and therewith should have brought to an end — an interpretation that has been demonstrably failed today, but disastrous in its worldwide impact. It served Heidegger primarily to reserve a “different start” in Western philosophizing. He tried this with the resumed question of the “meaning of being,” which he considered to be the original and actual of philosophy and which he tailored in his later work to simply listening to the belonging of human existence to an indeterminate “Seyn.” But it is still unclear what to do with it. With Heidegger himself, it was compatible with a deep commitment to National Socialism and with a radical critique of technology that seems monstrous today.

If nihilism is about major disorientation, you may have to start with it instead and then with the concept of orientation itself. Since Moses Mendelssohn and Immanuel Kant introduced him to philosophy in the course of a religious-philosophical dispute 250 years ago (this is a comparatively short time compared to the concept of substance, which is almost 2,500 years old), it had spread more and more and entered into common language usage. It was just that he had not yet really made it into philosophy: Nietzsche knew him, but barely used him, Wittgenstein already more, Heidegger began it in his early work Being and time To address, Jaspers immediately shortened it back to the orientation of philosophy in and through the sciences. If you now use and therefore need the concept of orientation everywhere, it is because you have to reorient yourself more or less at any time, in every new situation and no longer have absolute certainties, only clues. There is still much more to how we navigate the infinitely complicated reality with our limited equipment than you initially perceive and think, but nothing metaphysical, just more complex. This is true in astronomy, physics and biology as well as in everyday communication, politics, law, journalism, etc. This is most noticeable in criminology, from which television evenings largely live: It is always exciting to see what else could come out after the first inspection. Philosophically speaking, we only have clues everywhere for what we call “being,” “reality,” “truth,” points that we stick to for the time being and until further notice. And it is also becoming increasingly clear to everyone that everyone always orientates themselves from a point of view within limited horizons and perspectives, each with limited orientation skills, i.e. all orientation is ultimately individual. We must come to terms with this, and obviously we can. We can no longer be with an inherently existing existence, but must start with the orientation that is possible for us in our world. And you can no longer rely on the same common sense as you did 200 years ago, but you have to see how what you call “reasonable” comes about in communication. That can be very diverse.

What you observe in order to orient yourself is recorded in signs and interpreted in languages, which in turn can be interpreted differently in different situations and from different points of view. In the end, as the late Wittgenstein put it succinctly, you never know what the other person means with your signs and you yourself with your own signs.19 In all orientation, that means, possible disorientation plays a role. We must start from this today, and do so by giving our own orientation and our orientation towards each other, including in philosophy, scope for understanding everywhere. And Nietzsche said that too, in Beyond good and evil (No. 27; link), already expelled.

With the concepts of previous theory of knowledge, decision and action, you really have to start over if you want to understand how you understand the world and each other. First of all, this must be done descriptively, and now that the attachment to the otherworldly has proved indefensible, there is no longer a need for the distant pathos of preachers, in which philosophers like to indulge so much. Philosophy only becomes plausible if it stays close to everyday experiences. I am also trying, with the late Wittgenstein, “to return the words from their metaphysical ones back to their everyday use.”20, and yet to keep it at the level that philosophy has developed over its thousands of years of history.

The beginning of philosophizing seems simple because somewhere, on a small or large scale, you are disoriented, do not know your way around and want to get out of disorientation. It doesn't need more. What you then find are those clues to which there are always alternatives, so that you remain at a distance from them, only ever stick to them for the time being and therefore remain free to face them. Orientation on time could be the meaning of the big question of 'being and time', with which you can also do something in everyday life. This temporary orientation certainly includes philosophers “giving orientation”, also in the form of ethics with which they try to make the world better than it appears to them now. But this is also clearly always happening from specific points of view and on time, and here, too, there are always plausible alternatives.

What remains of the nihilism that Nietzsche proclaimed is the constantly unsettling uncertainty that things could always be different, that you could always see things differently from how you perceive them from your perspective. This keeps watchful for the possibility of other views. How much we need guidance because we constantly have to deal with situations in which we are only insufficiently familiar is nowhere more obvious than in the global crises that are now catching up with us. In the USA, people typically dare to do more. But as I am now experiencing, even in this country, more and more people, personally, in their professions and in the sciences they pursue, and also in their philosophizing, are able to make a new start in orientation themselves, without which there is nowhere. I'm happy about that.

IV. Philosopher's Hideouts

PS: Thank you very much for this comprehensive explanation of your own approach, which I hope will have a broad impact. Of course, this statement would provoke numerous inquiries — but perhaps we will have to make up for this on another occasion. Instead, I would like to round off this exchange with a somewhat different question: Nietzsche is a philosopher who speaks to a wide audience as strongly as few others, if only because of his lively style. Because people feel personally addressed by him; not only on an intellectual level, but not least on an emotional level. If I may now address not only the thinker, but also the person Stegmaier, with all his life experience: Is there a position at Nietzsche that has particularly touched you personally, that may have even shaped your personal career and that you would like to share with us?

WS: Yes, the position does exist and I would also like to share it with you at the end of our interview, for which I would like to thank you very much. It is about the “philosopher claim to wisdom“, and you have to listen to them — Nietzsche was just 43 years old when he published it, I'll be 80 soon — with a dash of irony. Often, he writes in Book V of Happy science (No. 359; link), which I appreciate so much, is the claim to wisdom, i.e. to philosophical teaching saturated with rich life experience,

a philosopher's hiding place, behind which he saves himself from fatigue, old age, cold, hardening, as a feeling of the near end, as the cleverness of that instinct that animals have before death — they go aside, become silent, choose solitude, hide in caves, become wisely... How? Does a philosopher's hideout suggest — the spirit? —

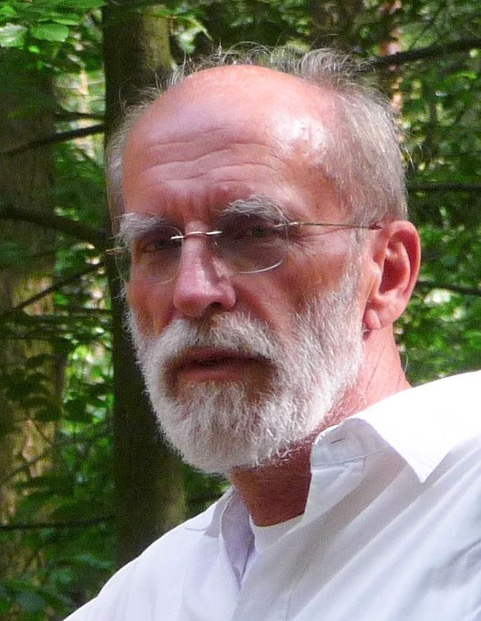

Werner Stegmaier, born on July 19, 1946 in Ludwigsburg, was professor of philosophy with a focus on practical philosophy at the University of Greifswald from 1994 to 2011. From 1999 to 2017, he was co-editor of Nietzsche studies. International Yearbook for Nietzsche Research, the most renowned body of international Nietzsche research, as well as the important series of publications Monographs and texts on Nietzsche research. He published numerous monographs and anthologies on Nietzsche's philosophy and philosophy in general, including Philosophy of orientation (2008), Nietzsche's introduction (2011) and Luhmann meets Nietzsche. Orientation in nihilism (2016) and recently Wittgenstein's orientation. Assurance techniques (2025). The development of the “philosophy of orientation” he founded is his current focus of work. Further information about him and his work can also be found on his personal website: https://stegmaier-orientierung.com/

Footnotes

1: Cf. abatement 1887, 9 [35]. In another place in the estate (1887, 9 [60]), it says: “Nihilism as a normal phenomenon.” Here too, “as a normal phenomenon” is added later.

2: The happy science, Aph 343.

3: Cf. abatement 1887 5 [71].

4: Editor's note: See also the article Look, I'm teaching you the transhumanist by Jörg Scheller (link).

5: Beyond good and evil, Aph 62.

6: Human, all-too-human, Vol. I, Aph. 24.

7: Ibid. See also the previous section (link).

8: Human, all-too-human, Vol. I, Aph. 25.

9: Cf. Beyond good and evil, Aph 251.

10: Human, all-too-human, Vol. I, Aph. 25.

12: Human, all-too-human, Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, Aph 275.

13: The Antichrist, No. 56 & 57.

16: substance. Basic concept of metaphysics (Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1977).

17: The philosophy of fluctuation. Dilthey and Nietzsche (Göttingen 1992).

18: On the genealogy of morality II, no 12.

19: Cf. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, SECTION 504.

20: Ibid., § 116.