#

war

Dionysus as Rolling Stone

An Attempt to Understand Nietzsche with Rock Music

Dionysos als rolling stone

An Attempt to Understand Nietzsche with Rock Music

On the one hand, Nietzsche's distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian helps to understand the development of the rock music of the Rolling Stones both internally and externally. On the other hand, Nietzsche's philosophy is reflected in many places in their songs. But above all, it is also illuminated by the Stones, and their songs show what Nietzsche is thinking — an Apollonian act. If Nietzsche is aesthetically oriented towards intoxication, then you can also learn from the Stones how to receive Nietzsche's poetry in a Dionysian way. It is therefore not just about understanding the Stones with Nietzsche, but vice versa: with the Nietzsche Stones.

An audiovisual version of this article with clips of the quoted songs can be found on the YouTube channel of the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy and on Soundcloud.

Nietzsche's Techniques of Philosophizing

With Side Views of Wittgenstein and Heidegger

Nietzsche's Techniques of Philosophizing

With Side Views of Wittgenstein and Heidegger

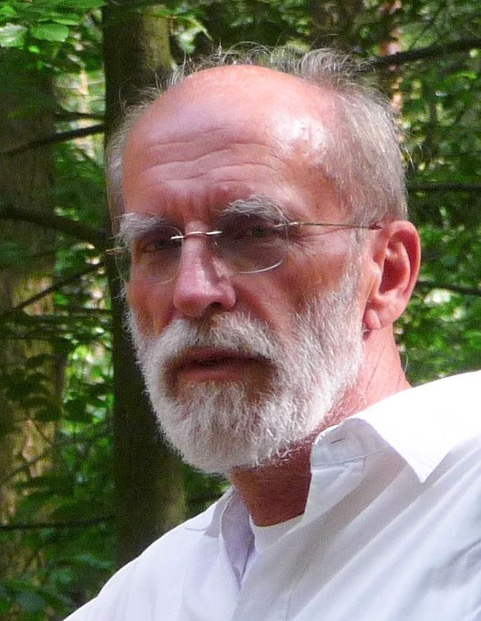

An integral part of the annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society is the “Lectio Nietzscheana Naumburgensis”, at which a particularly deserving researcher once again talks in detail about the topic of the congress on the last day and concludes succinctly. Last time, this special honor was bestowed on Werner Stegmaier, the long-time editor of the important trade journal Nietzsche studies and author of numerous groundbreaking monographs on Nietzsche's philosophy. The theme of the conference, which took place from 16 to 19 October, was “Nietzsche's Technologies” (Emma Schunack reported).

Thankfully, Werner Stegmaier allowed us to publish this presentation in full length. In it, he addresses the topic of the Congress from an unexpected perspective. This is not about what is commonly understood as “technologies” — machines, cyborgs, or automata — but about Nietzsche's thinking and rhetorical techniques. What methods did Nietzsche use to write in such a way that his work to this day not only convinces but also inspires new generations of readers? And what is to be said of them? He compares Nietzsche's techniques with those of two other important modernist thinkers, Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). In his opinion, all three philosophers say goodbye to the classical techniques of conceptual philosophizing founded in antiquity and explore radically new ones in order to try out a new form of philosophizing in the age of “nihilism.” A monotonous, metaphysical understanding of rationality is replaced by plural, perspective thinking, which must necessarily use completely different techniques. The article creates a fundamentally new framework for understanding Nietzsche's thinking and philosophical context.

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Nietzsche certainly did not have any children and is also not particularly friendly about the subject of fatherhood in his work. For him, the free spirit is a childless man; raising children is the task of women. At the same time, he repeatedly uses the child as a metaphor for the liberated spirit, as an anticipation of the Übermensch. Is he perhaps able to inspire today's fathers after all? And can you be a father and a Nietzschean at the same time? Henry Holland and Paul Stephan, both fathers, discussed this question.

We also published the complete, unabridged discussion on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy YouTube channel (Part 1, part 2).

Female Barbarians — When Women Become a Threat

Female Barbarians — When Women Become a Threat

In today's world, which wants to call itself modern and equal, old patterns continue to have an effect — rivalry instead of solidarity, adaptation instead of departure. The essay provocatively asks: Where are the barbarians of the 21st century? It shows the emergence of a new female force — a woman who does not destroy but refuses, who evades old roles and gains creative power from pain. Through examples from reality and literature, the text attempts to show that true change does not start in obedience but in bold “no” — and that solidarity among women could be the real revolution.

We awarded this text second place in this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing (link).

If you'd rather listen to it, you'll also find it read by Caroline Will on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy's YouTube channel (link) or on Soundcloud (link).

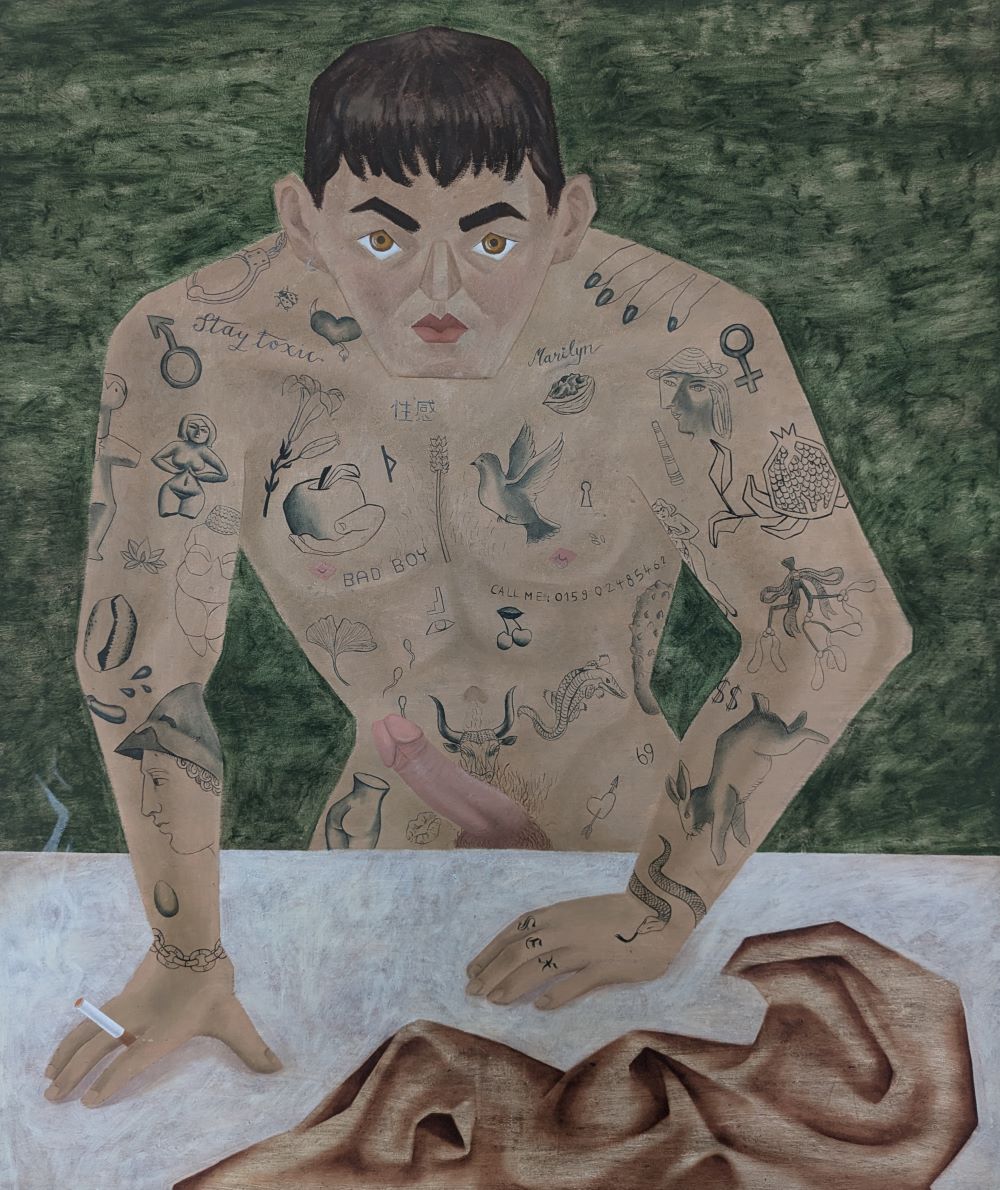

The Barbarians of the 21st Century

Narcissism, Apocalypse, and the Absence of Other

The Barbarians of the 21st Century

Narcissism, Apocalypse, and the Absence of Other

The diagnosis of our time: not heroic barbarians, but selfie warriors. This essay, which won the second place at this year's Kingfisher Award (link), explores Nietzsche's vision of the”stronger type”1 and shows how it is turned into its opposite in a narcissistic culture — apocalypse as a pose, the Other as a blind spot. But instead of the big break, another option opens up: a “barbaric ethic” of refusal, of ambivalence, of relationship. Who are the true barbarians of the 21st century — and do we need them anyway?

Nietzsche and the Philosophy of Orientation

In Conversation with Werner Stegmaier

Nietzsche and the Philosophy of Orientation

In Conversation with Werner Stegmaier

On the 125th anniversary of Nietzsche's death on August 25, we spoke with two of the most internationally recognized Nietzsche experts, Andreas Urs Sommer and Werner Stegmaier. While the conversation with Sommer (link) focused primarily on Nietzsche's life, we spoke with the latter about his thinking, its topicality and Stegmaier's own “philosophy of orientation.” What are Nietzsche's central insights? And how do they help us to find our way in the present time? What does his concept of “nihilism” mean? And what are the political implications of his philosophy?

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Individualism, even egoism, is frowned upon in all political, religious and social camps. They are attributed to liberalism and capitalism. Such people are not committed to others, are not involved politically or for the environment. They also do not respect a common understanding of the world and therefore behave irresponsibly. The Nietzschean is not impressed by such verdicts. She dances — not only!

Nietzsche and Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche and the Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche was repeatedly elevated to a figurehead by right-wing theorists and politicians. From Mussolini and Hitler to the AfD — Nietzsche is repeatedly seized when it comes to confronting modern society with a radical reactionary alternative. Nietzsche was particularly fascinating to intellectual right-wingers, such as authors like Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, who formed a cultural prelude to the advent of National Socialism in the 1920s, even though they later partially distanced themselves from it. People also often talk about the “Conservative Revolution”1.

What do these authors draw from Nietzsche and to what extent do they read him one-sidedly and overlook other potentials in his work? Our author Paul Stephan spoke about this with philosopher Robert Hugo Ziegler.

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

It is well known that Nietzsche had a hard time with women. His sexual orientation and activity are still riddled with mystery and speculation today. Time and again, this question inspired artists of both genders to create provocatively mocking representations. Can he possibly be described as an “incel”? As an involuntary bachelor, in the spirit of today's debate about the misogynistic “incel movement”? Christian Saehrendt explores this question and tries to shed light on Nietzsche's complicated relationship with the “second sex.”

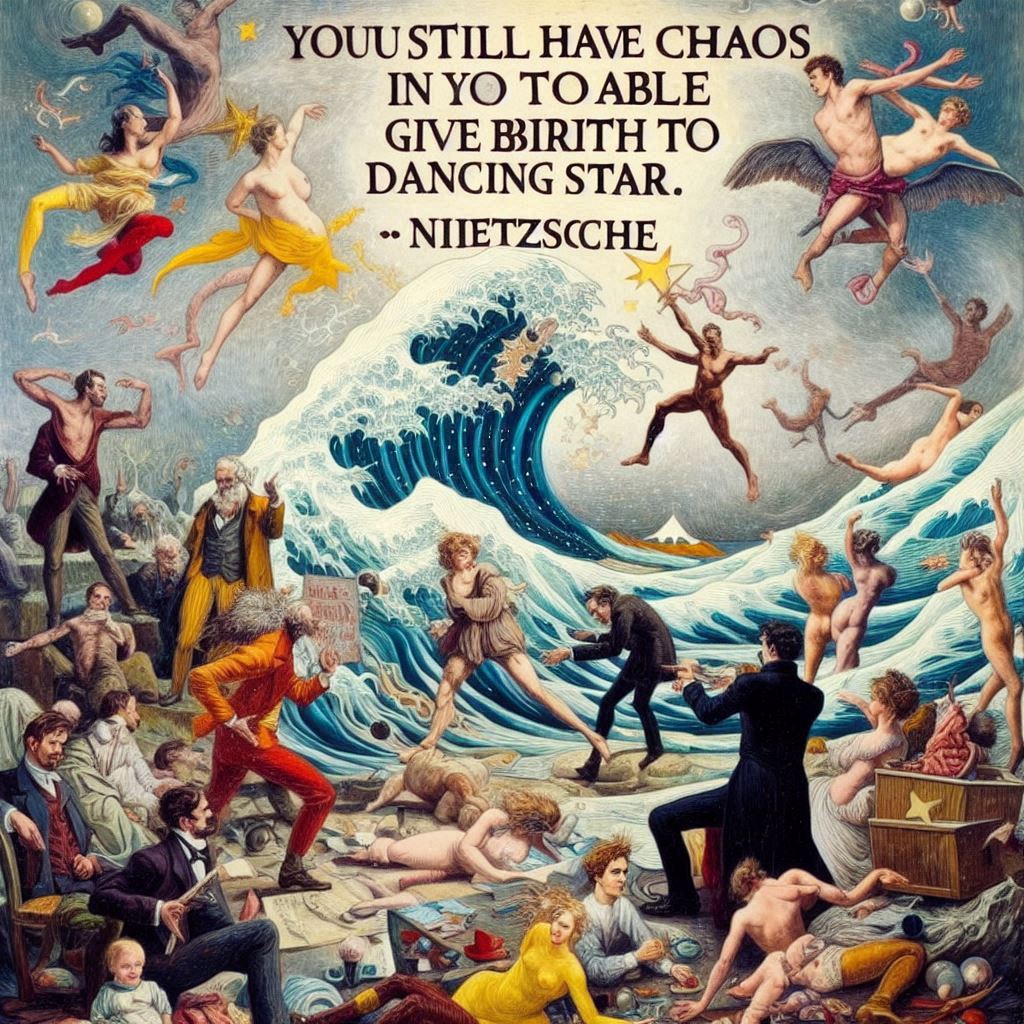

Can AI Give Birth to a Dancing Star?

Of Sparrows, Cannons and Decoys

Can AI Give Birth to a Dancing Star?

Of Sparrows, Cannons and Decoys

.jpg)

Like a year ago (link), our author Paul Stephan is also adding a commentary to this year's “dialogue” (link) with ChatGPT on the current state of thedevelopment of “artificial intelligence.” His assessment is somewhat more sober — but he does not want to be denied his fundamental optimism in technology. He also wants to avoid pessimism and naive hype, which is obviously being fueled right now to ensure that billions of dollars invested in AI are amortized.

We had various AI tools generate the images for this article at the following prompt: “Please give me a picture of the aphorism 'You still have to have chaos in yourself to be able to give birth to a dancing star' by Nietzsche,” one of ChatGPT's “favorite quotes” by the philosopher from Thus Spoke Zarathustra (link). The article image is from Microsoft AI.

Mythomaniacs in Lean Years

About Klaus Kinski and Werner Herzog

Mythomaniacs in Lean Years

Über Klaus Kinski und Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog (born 1942), described as a “mythomaniac” by Linus Wörffel, and Klaus Kinski (1926—1991) are among the leading figures of post-war German cinema. In the 70s and 80s, the filmmaker and the actor shot five feature films that are among the classics of the medium's history. They are hymns to tragic heroism, in which the spirit of Nietzsche can easily be recognized. From “Build Your Cities on Vesuvius! “will “Build opera houses in the rainforest! ”.

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Strangers seem creepy to many. They immediately fear that these strangers will harm them. Many decent earners think that recipients of citizen benefits are lazy and therefore do not allow them to receive government support. To many educated people, illiterate people appear rude and simple-minded, with whom they therefore want as little as possible nothing to do with, whom they do not trust. Religious people are often afraid of atheists, who in turn are afraid of contact with religion. What you don't know often appears to be dangerous and you prematurely discount that. Such prejudices lead to rejection, which often solidifies to such an extent that counterarguments are no longer even heard. This is resentment that has existed for a long time, but which today makes consensus almost impossible in many political and social debates. This can degenerate into hate and contempt and then into violence whether between rich and poor, right and left, machos and feminists, abortion opponents and abortion advocates, vegetarians and meat-eaters. When one side prevails, it imposes its values on the other, and the resentment even becomes creative. In any case, it prevents you from making an effort to understand the other person. For Nietzsche, resentment has been driving the dispute over what is morally necessary for a long time.

“Resentment” is one of the key terms of Nietzsche's late work. The philosopher is referring to an internalized and solidified affect of revenge, which leads to the development of an overall negative approach to the world. Especially in On the genealogy of morality Nietzsche is trying to show that the entire European culture since the rise of Christianity has been based on this affect. Judaism and Christianity, in their hatred of aristocrats, propagated an ethics of the weak — in this act, resentment became creative. With a new creative ethic, Nietzsche now wants to contribute to a renewed revaluation of values in order to return to a life-affirming aristocratic ethic of the “strong.” In this article, Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann introduces Nietzsche's reflections on resentment and works out what makes the accusation of mutual resentment so popular to this day.

Traveling with Nietzsche through Southeast Asia IV

Malaysia

Traveling with Nietzsche through Southeast Asia IV

Malaysia

The last country that our author, Natalie Schulte, traveled by bike was Malaysia. After a good 5,000 km, she got the creeping feeling that the trip could still end poorly. With considerations as to whether cycling in Southeast Asia is a response to Nietzsche's appeal “live dangerously! “, she concludes her series of essays.

“Choose the right time to die!”

Nietzsche's Ethics of “Free Death” in the Context of Current Debates About Suicide

A Conversation with Filmmaker Lou Wildemann

“Choose the right time to die!”

Nietzsche's Ethics of “Free Death” in the Context of Current Debates About Suicide. A Conversation with Filmmaker Lou Wildemann

Lou Wildemann is a cultural scientist and filmmaker from Leipzig. your current feature film project, MALA, deals with the suicide of a young resident of Nietzsche City. Paul Stephan discussed this provocative project and the topic of suicide in general with her: Why is it still taboo today? Should we talk more about this? What role can Nietzsche's reflections, who repeatedly thought about this topic, play in this? What does suicide mean in an increasingly violent neoliberal society?

Homesick for the Stars

Prolegomena of a Critique of Extraterrestrial Reason

Homesick for the Stars

Prolegomena of a Critique of Extraterrestrial Reason

On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin achieved the unbelievable: He was the first person in history to leave the protective atmosphere of our home planet and circumnavigate the Earth in the Vostok 1 spaceship. In 2011, the anniversary of this “superhuman” act was declared International Manned Space Day. The stars aren't that far away anymore. With the technical progress achieved, the fantasy of expanding human civilization into space takes on concrete plausibility. The following text attempts to philosophically rhyme with these prospects and finally describes the approach of a possible space program from Nietzsche. Although airplanes didn't even exist during his lifetime, his concepts can still be applied to this topic in a productive way, as is so often the case.

Editorial note: We have explained some difficult technical terms in the footnotes.

Discourse, Power and Delusion

Michel Foucault's Nietzsche Interpretation Revisited

Discourse, Power and Delusion

Michel Foucault's Nietzsche Interpretation Revisited

The humanities scene recently experienced a minor sensation: In the estate of Michel Foucault (1926—1984), one of the most important representatives of post-structuralism, its editors came across an elaborate book manuscript with the title Le discours philosophique, on which the avowed Nietzschean had worked in 1966. It was published in German by Suhrkamp in 2024. Nietzsche plays a decisive role in this comprehensive analysis of philosophical discourse since Descartes. Paul Stephan takes this event as an opportunity to take a closer look at the most influential Nietzsche interpretation of the 20th century to date.

Fleeing the State: Kafka and Nietzsche’s Human

Or: Becoming-woman after Deleuze & Guattari

Fleeing the State: Kafka and Nietzsche’s Human

Or: Becoming-woman after Deleuze & Guattari

Kafka and Nietzsche are united by their confrontation with the state and bureaucracy. Deleuze & Guattari, whose works are based on both, develop an apolitical response to the fatal political situation, namely transformations after Kafka, an expansion of themselves to Nietzsche, which can be understood as escape lines from a patronizing society.

A Philosophical Serenade About Grayness

A Summer Evening with Sloterdijk at Gütchenpark in Halle

A Philosophical Serenade About Grayness

A Summer Evening with Sloterdijk at Gütchenpark in Halle

One of the most important philosophers of our time, Peter Sloterdijk (born 1947), visited Halle at the beginning of July. The thinker, who was heavily influenced by Nietzsche, shared his thoughts about “gray” there and impressively showed the heights to which philosophy can rise.

Nietzsche and Ukraine

A Conversation with Vitalii Mudrakov

Nietzsche and Ukraine

A Conversation with Vitalii Mudrakov

Vitalii Mudrakov is one of Ukraine's leading Nietzsche experts. Due to the war, he and his family currently live in Germany. Paul Stephan talked to him in detail about some aspects of the rich Ukrainian reception of Nietzsche in the context of the country's independent cultural history, which has often been ignored. It shows that Nietzsche's liberal thinking repeatedly inspired central protagonists of Ukrainian culture in their struggle for an independent nation free from Habsburg, Tsarist or Soviet foreign rule — and today again the struggle for their own self-assertion in the face of the Russian invasion.

Boomers, Zoomers, Millennials

How Do the Respective Perspectives on Nietzsche Differ?

Boomers, Zoomers, Millennials

How Do the Respective Perspectives on Nietzsche Differ?

This time in confidential Du, Paul Stephan talked to Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann, our oldest parent author, and our youngest regular author, Estella Walter, about our different generational experiences and about what is actually to be thought of the fashionable discourse about the different “generations.” We talked about post-structuralism, the ecological issue and the diversity of possible connections to Nietzsche.

Better to Want Nothing, Than Not to Want at All

Self-Alienation through Modern Science

Better to Want Nothing, Than Not to Want at All

Self-Alienation through Modern Science

Nietzsche's criticism of science is perhaps one of the most provocative, but also the most relevant, sub-areas of Nietzsche's comprehensive critique of modern culture. Estella Walter reconstructs her perhaps most important formulation in the third treatise of The genealogy of morality and shows how Nietzsche's science is a form of estrangement Understands. She explains this concept, which is so central to modern philosophy, and bridges it from Nietzsche to (young) Marx: Both are critics of the alienations of the modern way of life, whose critiques we should read together in order to reach a comprehensive understanding of it.

Determining Nietzsche

Determining Nietzsche

Does Nietzsche have clear philosophical doctrines? There is still a fight with Nietzsche's ambiguity today. When does he mean what he says? In her essay, Natalie Schulte explores the question of where, in the midst of assimilating ambiguity through ideological programs on the one hand and academically savvy dispersal of Nietzsche's thought structures into indiscriminate and incoherent fragments and perspectives, on the other hand, today's engagement with Nietzsche has to locate its decisive challenges. Between the dangers of confusing his philosophy and the limitless relativization of his theses, she is looking for a fruitful third way of dealing with the question of the “actual Nietzsche.”

The Enlightenment’s Twilight

Nietzsche's Truth of Semblance II

The Enlightenment’s Twilight

Nietzsche's Truth of Semblance II

After Michael Meyer-Albert in the first part of his text Telling the sad story of the self-doubt of the Enlightenment, he now reports on Nietzsche's “cheerful science” as an alternative.

The Enlightenment’s Twilight

Nietzsche's Truth of Semblance I

The Enlightenment’s Twilight

Nietzsche's Truth of Semblance I

Nietzsche's best-known formulation, according to which God is dead, not only shows an anti-religious thrust. In particular, it points out that in modern times, constitutive self-evident elements no longer have traditional validity. As the cultural understanding of truth has faltered, not only has this or that truth become questionable, but the understanding of what truth actually is. This puts enlightenment under pressure to find the questions to which it should be the answer. It is this abyss of uncanny questionability from which Nietzsche's thinking attempts to show ways out that are viable. In the first part of his text Enlightenment Twilight Michael Meyer-Albert talks about the clarified doubts of the Enlightenment about itself.

“Je suis Nietzsche!”

A Dialogue about Bataille, Freedom, the Economy of waste, Ecology and War

“Je suis Nietzsche!”

A Dialogue about Bataille, Freedom, the Economy of waste, Ecology and War

Paul Stephan talked to Jenny Kellner and Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann about the interpretation of one of the most important Nietzsche interpreters of the 20th century: Georges Bataille (1897—1962). The French writer, sociologist and philosopher defended the ambiguity of Nietzsche's philosophy against its National Socialist appropriation and thus became a central source of postmodernism. Based on Dionysian mythology, he wanted to develop a new concept of sovereignty that transcends the traditional understanding of responsible subjectivity, and criticized modern capitalist rationality in the name of an “economy of waste.” With all this, he provides important impulses for a better understanding of our present tense.

The Desire for Waste

The Desire for Waste

What significance can a practice of waste have in today's advanced rationalization? Shouldn't we rather do everything we can to increase our efficiency and productivity if we want to meet the challenges of this crisis-ridden time? But when we turn to the thinking of Friedrich Nietzsche and his ardent admirer Georges Bataille, we are sometimes exposed to an emphasis of waste that shakes our moral principles and perhaps opens us up to a new and different kind of politics than the one that seems to impose itself on us today as having no alternative.

The Enduringly Contested Friedrich Nietzsche

Report on the Annual Meeting of the Nietzsche Society 2023

The Enduringly Contested Friedrich Nietzsche

Report on the Annual Meeting of the Nietzsche Society 2023

From October 12 to 15, the annual meeting of the Friedrich-Nietzsche Society took place in Naumburg. Numerous experts from all over the world came together to explore the various causes of Nietzsche's impact in the first decades following his mental collapse. The spiritual struggles over Nietzsche repeatedly referred to the real struggles of the past — and those of our present.