Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

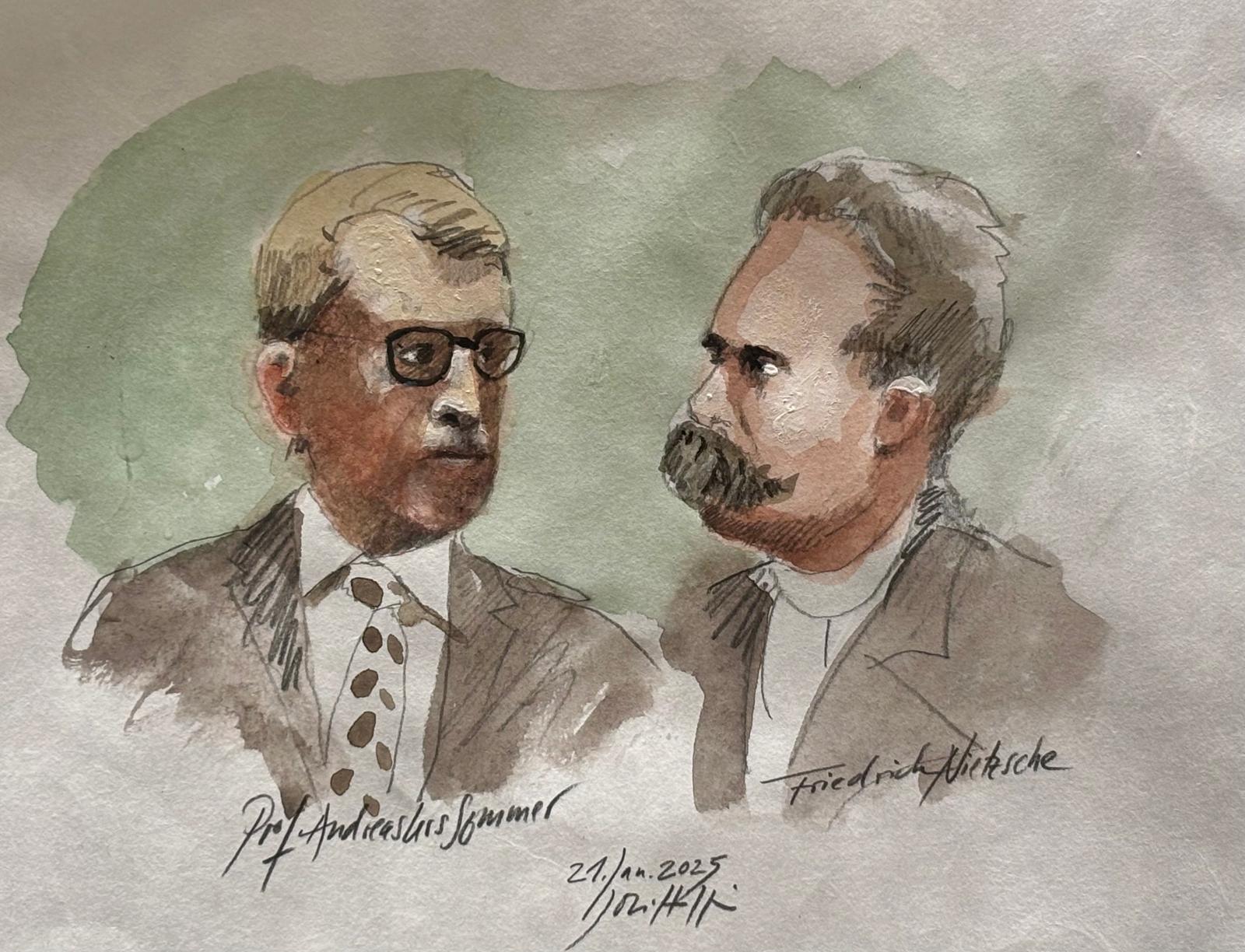

It is well known that Nietzsche had a hard time with women. His sexual orientation and activity are still riddled with mystery and speculation today. Time and again, this question inspired artists of both genders to create provocatively mocking representations. Can he possibly be described as an “incel”? As an involuntary bachelor, in the spirit of today's debate about the misogynistic “incel movement”? Christian Saehrendt explores this question and tries to shed light on Nietzsche's complicated relationship with the “second sex.”

I. Why did Nietzsche live ascetically?

“Nietzsche and physical love” — this title would probably adorn the thinnest chapter in the thick book of his life story. He was single and never lived in a partnership. There is no evidence whether he was homosexual or asexual, and whether he ever had sexual intercourse at all. The alleged syphilis infection, which could serve as evidence of at least one single act, is doubted from today's perspective. His sister Elisabeth wrote about Frederick's love life:

His infatuation never rose above moderate, poetically inspired, heartfelt affection. How the great passion, the vulgar love, has remained completely removed from my brother's entire life. His whole passion lay in the world of knowledge...1

Did Nietzsche live like a monk of his own free will? Or would you count him among the involuntarily celibate men, tens of thousands of whom today are known as “Incels” (Involuntary celibate) form a misogynistic movement that is primarily active online, but has also produced murderers and gunmen. In the USA and Canada alone, they have killed fifty people, primarily women, since 2014. The assassin from Halle, who shot two people in his anti-Semitic attack in 2019, was also connected to the incel scene. In Incels' imagination, men are divided into three classes: attractive “alphas”, average “Normies” and, as a group of losers, the Incels, who go empty-handed when looking for partners. These young men have a traditional image of masculinity, but at the same time experience that they do not live up to their own ideal. They hate themselves and especially women for not being compliant with them. Right-wing extremists, influencers and commercial pick-up artists cultivate this negative identity and exploit the incels. They are convinced that they are victims of an overly liberalized society that gives women excessive freedoms and that men have a kind of fundamental right to sex, which is denied them “by the system.”2

II. Women and “women” in Nietzsche's work

Notwithstanding a lack of practice in matters of love and partnership, Nietzsche occasionally painted himself as a woman expert in his writings. In particular, there is a passage from Ecce homo, “Why I write such good books” (link) , in which several aspects of female identity, emancipation and sexuality are discussed, some of which reflect the current sexist and biological views of the 19th century and would at the same time fit today's Incel ideology. It is therefore not surprising that Nietzsche is misunderstood as the “godfather of all today's incels” in various online forums such as Reddit or Quora.3 The following quotes from Nietzsche are all of the above Ecce homo-Excerpt from the text. The first appears like impostor compensation in the context of self-identification with Dionysus:

May I dare to assume that I am the woman Know? It's part of my Dionysian dowry. Who knows? Perhaps I am the first psychologist of the eternal feminine. They all love me [.]

It is remarkable that Nietzsche seemed to be very progressive on one point in the context of his image of women: He approved that women had the right to full enjoyment of sexual intercourse — an outrageous “immoral” position at the time:

[T] he preaching chastity is a public incitement to repentance. Every contempt for sexual life, every contamination of it by the term “unclean” is the crime itself alive — is the actual sin against the Holy Spirit of life.

According to Nietzsche, however, the biological purpose of reproduction is paramount. Women should not be denied their erotic desire because procreation is their actual purpose in life and many other things (such as studying, writing, culture) only distracts them from it. This distraction leads to pathological and unfortunate conditions, with only therapy helping: “Have you heard my answer to the question of how to treat a woman cures — “redeemed”? You make him a child. ”

In this context, Nietzsche also pathologizes all emancipation efforts:

The battle for Equal Rights is even a symptom of illness: every doctor knows that. — The woman, the more woman she is, defends herself with hands and feet against rights in general: the state of nature, the eternal war Between the sexes, he is by far the first place.

Nietzsche therefore sees women at an advantage in the gender war of the state of nature, which is why he considers the use of women's rights activists paradoxical and self-destructive. Legally regulated emancipation is something unnatural: “'Emancipation of woman' — that is the instinct hate of misguided, That means childbearing women against the well-behaved — the fight against the 'man' is only ever a means.” Nietzsche summarizes almost resigned: “The woman is unspeakably much more angry than the man, even smarter; kindness towards a woman is already a form of degeneration.”

By stressing the predatory dangerousness, malice, and superiority of women, Nietzsche delivers en passant An explanation for his lack of commitment:

Fortunately I am not willing to let myself be torn apart: the perfect woman tears apart when she loves... I know these lovely maidends... Ah, what a dangerous, sneaking, underground little predator!

While Dionysus was often portrayed positively in the 19th century, although he was also described with traits that were considered typically feminine in that era, his female companions, the Bakchai or Maenades, were mostly characterized as insane and spanning. This subsequent devaluation of the ancient Greek manad cult is to be regarded as a typical expression of misogyny.4 Nietzsche is no exception. Symbolized by the maenades, he sees women as a being dominated by sexual obsessions: “The tremendous expectation of sexual love spoils women's eye for all distant perspectives,” he wrote to Lou Andreas-Salomé, whom he adored.5

In Beyond good and evil He summarizes once again why women are actually far too dangerous for men:

What inspires respect and often enough fear in women is their nature, which is more natural than that of men, their genuine, predatory, cunning suppleness, their tiger claw under the glove, their naivety in egoism, their incomprehensibility and inner savagery, the incomprehensible, expanse, wandering of their desires and virtues.6

In an interesting analogy in the Preface of Beyond good and evil Nietzsche equates truth with the feminine and describes the inability of philosophers to approach, woo and conquer it:

Assuming that the truth is a woman — is there no reason to suspect that all philosophers, provided they were dogmatists, understood women poorly? That the gruesome seriousness, the left-wing intrusion with which they used to approach the truth up to now, were clumsy and unseemly means of taking over a woman's room for themselves? It is certain that she did not allow herself to be taken.

Did the ridicule figure of the “left-wing, obtrusive” and at the same time “gruesome and serious” dogmatist also contain a bit of self-irony?

III. Nietzsche's relations with women

Biographical research gave various reasons for Nietzsche's lack of love life. Helmuth W. Brann speculated almost 100 years ago in his book Nietzsche and the women about Nietzsche's lack of sex appeal and his resulting frustration.7 Adorno placed in the Minima Moralia It is astonishing that Nietzsche “adopted the image of female nature unchecked and inexperienced from Christian civilization, which he otherwise so thoroughly distrusted. ”8 Martin Vogel characterized Nietzsche as “erotically weak.” His image of women is of “appalling poverty and independence.”9 been. According to Pia Volz, Nietzsche “idealized his schizoid-narcissistic relationship disorder as a heroic loneliness gesture.”10 and manifested in the figure of Zarathustra.

Nietzsche had several older girlfriends such as Malwida von Meysenbug, Zina von Mansurov or Marie Baumgärtner — the mother of one of his students. Nietzsche asked for a young woman's hand three times. He also maintained contact with younger students, music lovers and readers of his works. In contradiction to his written statements about the role of women in society, which were strongly influenced by the discriminatory biological ideas of his time, Nietzsche maintained acquaintances and friendships with writing and philosophizing women. The 1848 revolutionary and Wagnerian from Meysenbug, who Nietzsche as the “best [] friend in the world” vis-a-vis third parties11 called, may even be regarded as a pioneer of women's emancipation, which Nietzsche vehemently rejected. Nietzsche was also familiar with several lesbian women, in addition to the Swiss feminist Meta von Salis, these included the then medical student Clara Willdenow and the philosopher Helene von Druskowitz. His reactionary views on women's rights did not seem to be an obstacle to friendship for them, except for von Druskowitz, who vehemently distanced herself from Nietzsche in 1886 and “settled accounts” with him in publishing.12

“Nietzsche was the type of mother's son,” stated Vogel, “even during his time as a student and professor, he primarily sought to assure himself of the goodwill of older experienced women.”13, for example Sophie Ritschl, his teacher's wife in Leipzig, Ottilie Brockhaus, Richard Wagner's sister, and, as mentioned, Malwida von Meysenbug. With Malwida, who was 28 years older, Nietzsche also spent the vacation approved by the University of Basel in 1876. “In the case of older women, the last remnant of timid anxiety usually disappeared and Nietzsche moved in completely informal security and suddenly open-minded agility. ”14

In spring 1876, Nietzsche asked for the hand of the young Russian woman Mathilde Trampedach, who was in Geneva and had met only three times before. Trampedach took piano lessons with composer Hugo de Senger in Geneva — and had fallen in love with him (which Nietzsche may not have known). Nietzsche sent her the marriage proposal in writing on April 11, 1876, in consultation with de Senger.15 Trampedach politely declined (and married de Senger soon after), while Nietzsche apologized profusely for his move by letter on April 15 (link). A few weeks later, in Bayreuth, he fell in love with the young music lover Louise Ott, who, however, was already married to a banker and mother.16

In Nietzsche's marriage plans of those years, the idea of economic security certainly also played a role, which had become all the more urgent after the resignation of his Basel professorship. In a letter to his sister dated April 25, 1877, he describes a plan that he had devised together with Malwida: “The marriage with a suitable but necessarily wealthy woman” would enable him to give up the health-burdensome teaching activity and “with this (woman) I would then live in Rome for the next few years [...] according to the spiritual qualities I always find Nat [alie] hearts most suitable.” (link) He had already met sisters Natalie and Olga Herzen, exiled Russians, with Malwida in Bayreuth in 1872. They shared a common taste in music, and Nietzsche initially had Olga Herzen in mind.17 His interest later shifted to Natalie. However, there were never any more serious advances. In 1877, Nietzsche Malwida wrote: “Until autumn I still have the wonderful task of winning over a wife, and if I had to take her [sic] off the alley,”18 But at the same time he was pessimistic about his sister: “The marriage, very desirable indeed — is the most unlikely thing, I know that very clearly! ”19 In late summer, he knocks on Malwida again about this issue: “Have you found the female fairy who releases me from the column I am forged to? ”20

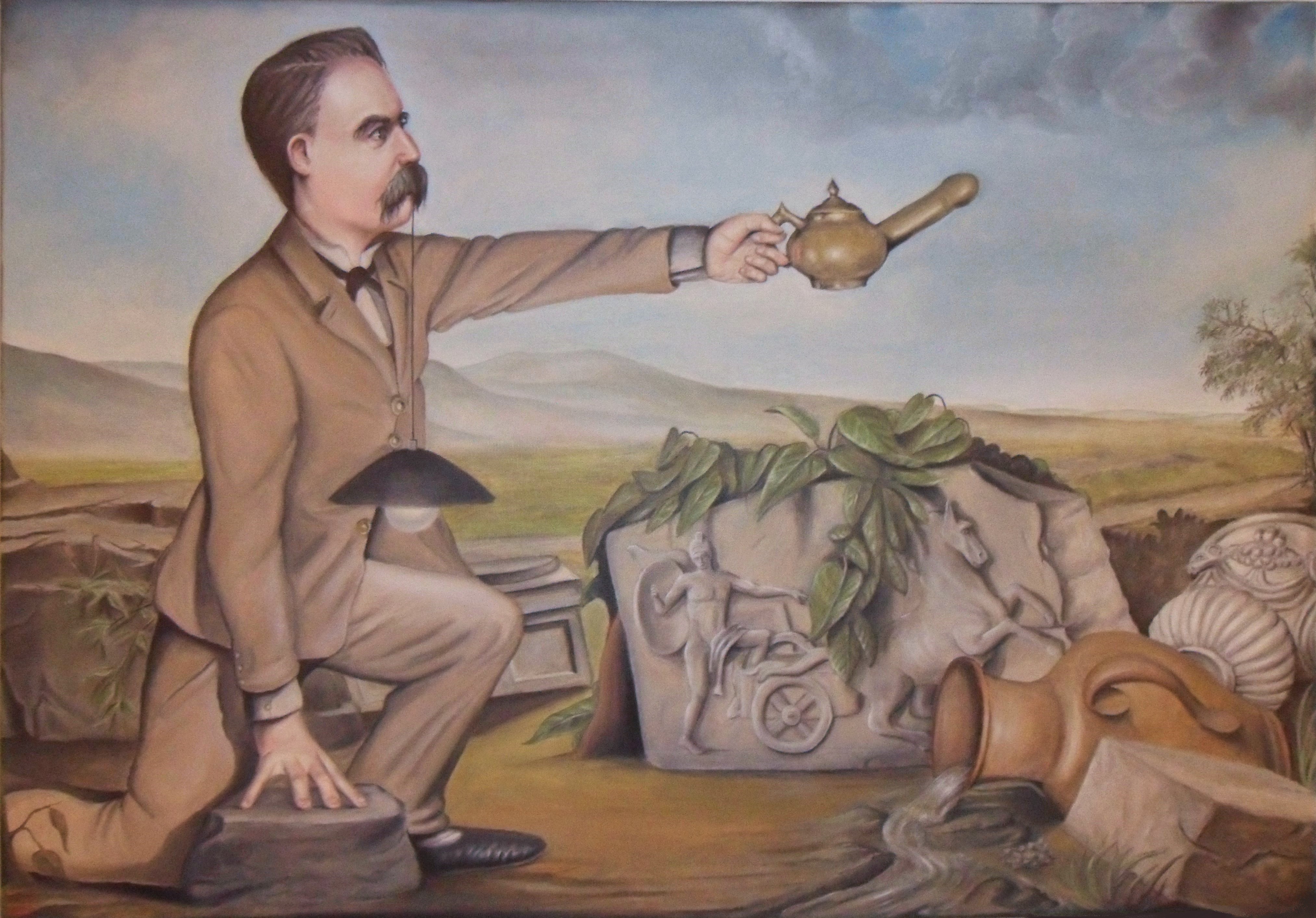

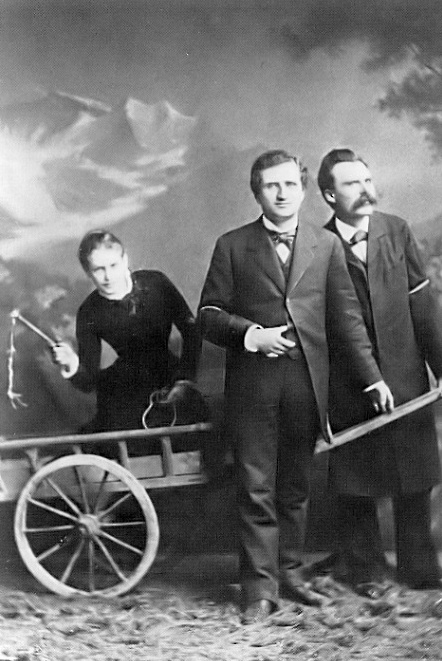

In the spring of 1882, Nietzsche submitted a marriage proposal to the German-Russian philosophy student Lou Andreas-Salomé through Paul Reé in Italy, without knowing that he himself had already presented her with regard to marriage. On May 13, 1882, Nietzsche repeated the request at another meeting in Lucerne. Lou turned down both applications and then lived with Reé, which disappointed Nietzsche. However, in retrospect, in conversation with Ida Overbeck, he gave the impression that his application was about to be rejected by Lou, and only Pro forma was done for moral and social reasons.21 After rejecting his marriage proposal, Nietzsche had persuaded Rée and Lou in Lucerne to take a staged photograph in which the two men pull a car with the whip-wielding Lou in front of the photo studio backdrops, making both the car and the whip ridiculously small, giving the scene a comically ironic expression. Shortly thereafter, Nietzsche used the whip motif in the first part of the Zarathustra: “You go to women? Don't forget the whip! ”22 — it should remain one of his most famous quotes today. Years later, long after Nietzsche broke with Wagner, Lou traveled to Bayreuth and once showed the whip photograph around as a curiosity that Nietzsche's sister did not like at all.23

Malwida apparently did not lose sight of the project of Nietzsche's marriage in the following years and repeatedly introduced him to young women. In 1884, he met Resa von Schirnhofer in Nice. Schirnhofer, ten years younger than Nietzsche and a philosophy student in Zurich, was apparently regarded by Malwida as a suitable marriage candidate for him, but there was no connection between the two.

“What are all the young or less young girls doing, with whom I owe their friendship (lots of crazy little animals, said among us)? “he asked in a letter to Malwida at the end of February 1887 (link) and complained that his younger acquaintances had not been heard from him for a long time.

In the Trampedach and Andreas-Salomé cases, the question is whether Nietzsche was even seriously thinking of marriage, because in both cases he involved direct competitors and then lost out on them. It almost seems as if he had wished for the applications to be rejected. It is also noticeable that Nietzsche has repeatedly chosen the role of an asexual-platonic “third party in the league”, for example with Franz and Ida Overbeck, as well as with Paul Rée and Lou as well as with Cosima and Richard Wagner. In this way, he was able to escape a closer bond and say goodbye to this constellation at any time. Nietzsche's tendency to make friends with lesbian women also fits into the pattern of avoidance, because they posed no “danger” in terms of sex and partnership. All in all, you get the impression that Nietzsche's marriage ambitions were not very stringent over the years and may not have been intentional at all. Perhaps he even liked to live alone and ascetically? In the third treatise of The genealogy of morality Nietzsche deals critically or mockingly with the social functions of ascetic ideals, but also points out: “A certain ascetism, we saw it, a hard and cheerful renunciation of the best will is one of the favorable conditions of the highest spirituality.”24. In the end, it remains unclear whether Nietzsche deliberately lived ascetically and actually did not need any partners at all, or whether he made a virtue out of necessity.

IV. Is Nietzsche's syphilis the reason for his celibate lifestyle?

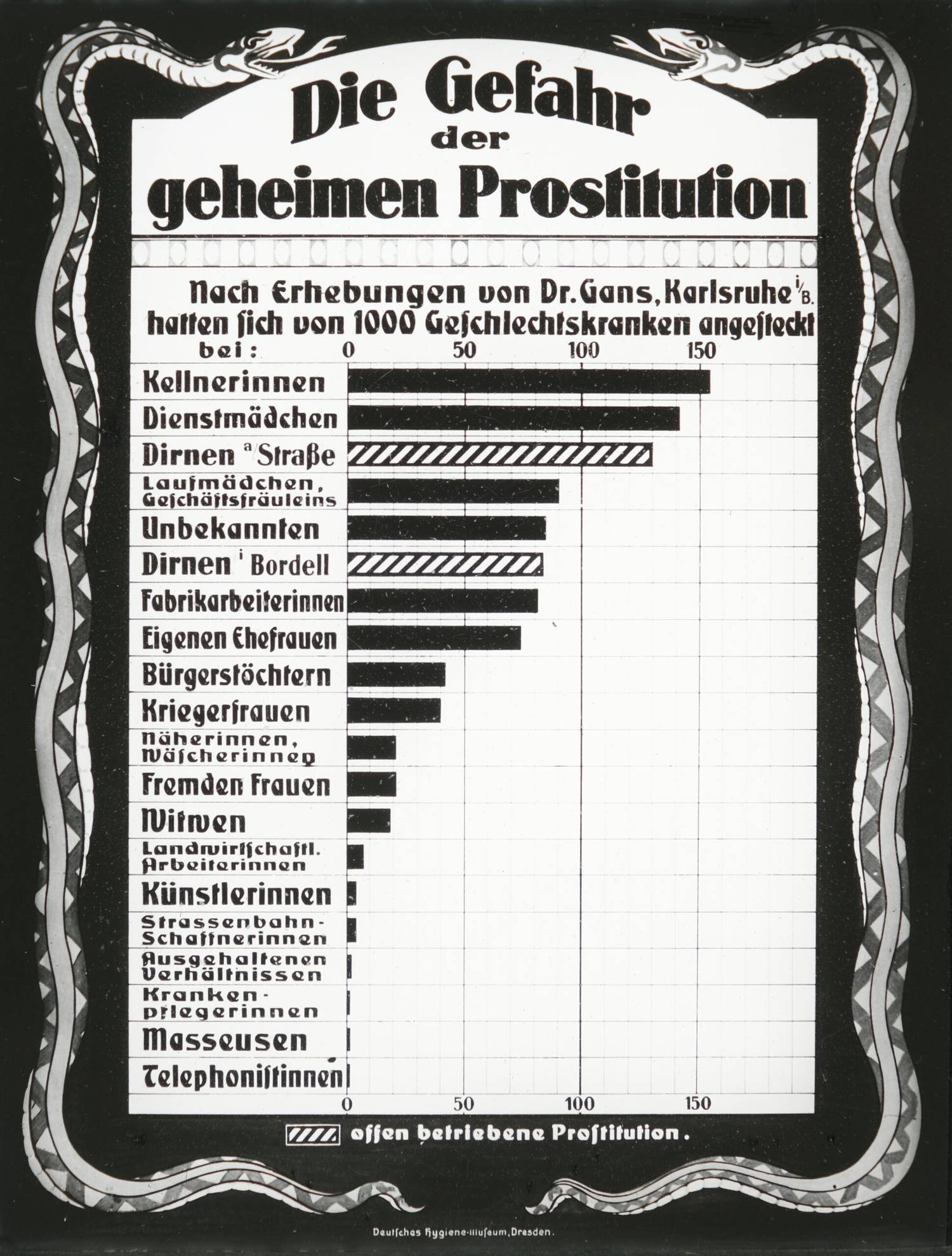

In the end, the question should be investigated as to whether Nietzsche's illness could have been the reason for his celibate lifestyle. In the 19th century, there were cases in which bourgeois men infected with syphilis remained single out of a sense of moral responsibility because they did not want to expose their wives and children to the risk of infection. Whether Nietzsche actually ruled out marriage for this reason, but was unable to explain it to third parties? Nietzsche is said to have received medical treatment for a syphilitic disease (“Lues”) during his time in Leipzig, but gonorrhea was also diagnosed with this term at that time until the gonorrhea pathogen was detected in 1879.25 In 1875, Nietzsche was diagnosed with chronic chorioretinitis for the first time, which in some cases occurs as a result of syphilis and was interpreted as an indication that he had contracted it during his studies in Leipzig.26 In the case of an actual syphilis infection, the question was why he did not mention the diagnosis and symptoms in any of his letters, even though he otherwise provided detailed information about any health conditions and problems. Perhaps the shame was too great. In the 19th century, the issue of syphilis was morally burdened and socially stigmatized. The disease was initially regarded as a side effect of prostitution and as a “punishment” for “sinful” sex workers and adulterers, but over the course of the century it was regarded more and more as a threat to marriage and family, and therefore to “public health.” Although the thesis of the heredity of the disease, which emerged around 1875, relieved the infected on the moral level, the horrors of the “progressive paralysis” diagnosed as a long-term consequence and the untreatability of the disease remained present and ensured a strong presence of the epidemic in science and culture.27 Syphilis phobia also undermined the diagnosis of “neurasthenia,” a complex, psychosomatic nervous state, whose symptoms fatally matched the early stage of progressive paralysis and further increased syphilisphobia. In any case, at the end of the 19th century, syphilis was considered a disease that was interpreted as a sign of social decay and as a threat to “public health.” Bourgeois men often reacted to a diagnosis in panic, occasionally even with suicide,28 They often saw themselves no longer suitable for a civil marriage.

In the end, Nietzsche's symptoms were never clarified. Clinical treatment and biographical research have included chloral hydrate poisoning, mental overwork, schizophrenia, epilepsy, dementia, mania and depression. For a long time, the diagnosis of his treating doctors dominated, who identified “progressive paralysis” as a long-term consequence of syphilis in 1889. In recent decades, this has been increasingly called into question and new diagnoses and theories (as far as this is posthumously possible at all) have been added, such as a brain tumour in the eye nerve, CADASIL syndrome or MELAS syndrome.29

The question of why Nietzsche remained single and chaste throughout his life cannot be conclusively answered. His relationship with women had no physical dimension, but rather complex mental aspects. He is hardly likely to serve as the godfather of today's Incel movement; his worldview and self-image were too differentiated for that. He didn't blame anyone for his loneliness. It seems paradoxical today that he adopted the usual sexist attitudes of the 19th century — that procreation, for example, was a woman's real purpose in life — and yet longed for recognition from an intelligent and educated woman: “The safest way to combat a man's disease of self-loathing is to be loved by a clever woman. ”30

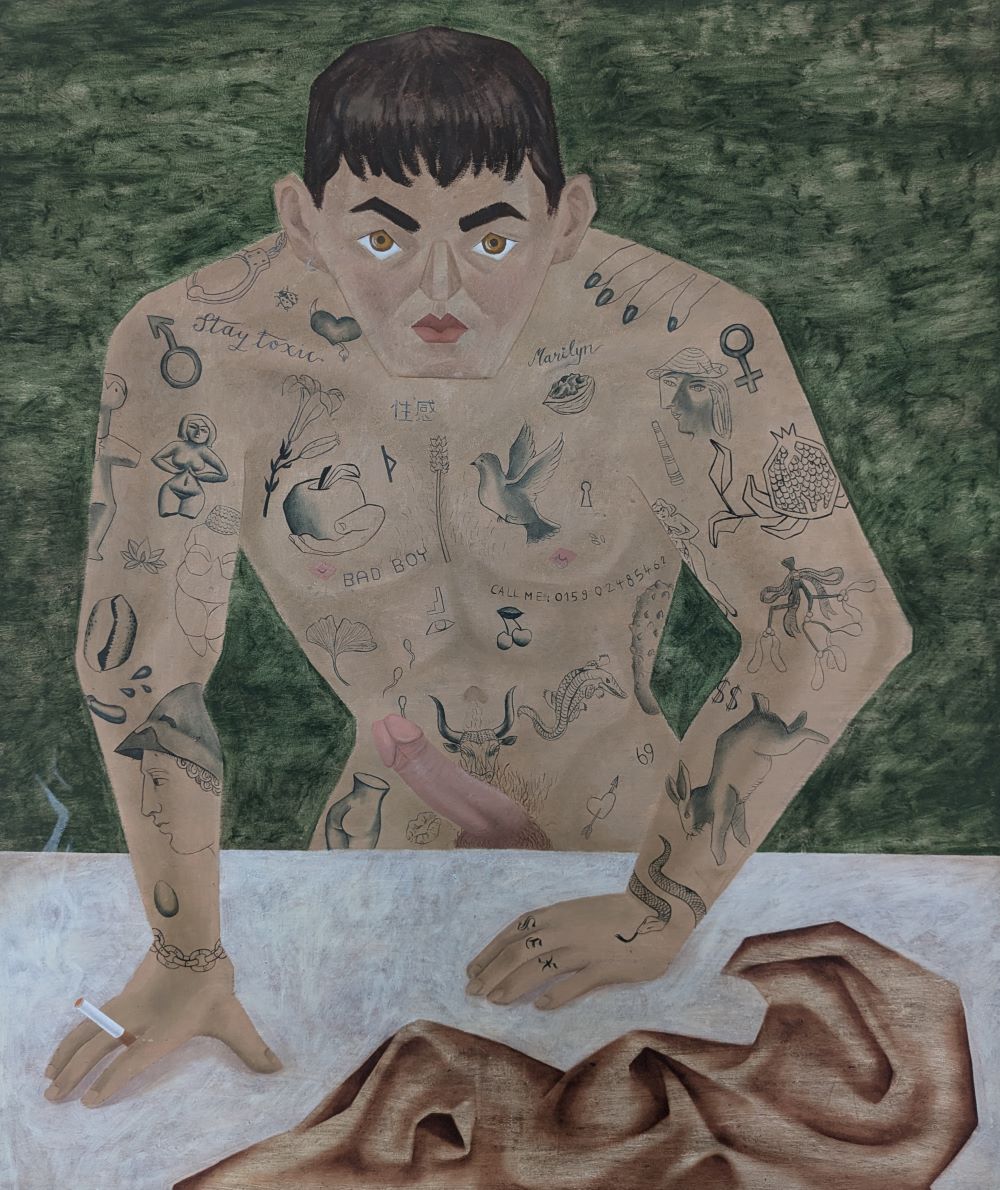

Source of the article image

Salwa Wittwer (Leipzig): Stay Toxic. Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm, 2024, owned by the artist.

Literature

Adorno, Theodor W.: Minima Moralia. Reflections from damaged life (1951). Frankfurt am Main 1978.

Brann, Helmuth Walter: Nietzsche and the women. Leipzig 1931.

Diethe, Carol: women. In: Henning Ottmann (ed.): Nietzsche Handbook. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 50—56.

This. : Forget the whip. Nietzsche and the women. Hamburg 2000.

Foerster-Nietzsche, Elisabeth: The life of Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. 1. Leipzig 1895.

Kirakosian, Racha: Intoxicates deprived of senses. A story of ecstasy, Berlin 2025.

Niemeyer, Christian: Nietzsche's syphilis — and that of others. Baden-Baden 2020.

Radkau, Joachim: Malwida from Meysenbug. Revolutionary, poet, girlfriend: A woman in the 19th century. P. 360.

Schonlau, Anja: Syphilis in literature. On aesthetics, morality, genius and medicine (1880-2000). Würzburg 2005.

Tényi, Tamás: The Madness of Dionysus — Six Hypotheses on the Illness of Nietzsche. In: Psychiatria Hungaria 27/6 (2012), P. 420-425 (link).

Vogel, Martin: Apollinan and Dionysian. Story of a brilliant mistake. Regensburg 1966.

Volz, Pia: Nietzsche's disease. In: Henning Ottmann (ed.): Nietzsche Handbook. Stuttgart 2000, p. 57 f.

Footnotes

1: Elisabeth Foerster-Nietzsche, The life of Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. 1, p. 180.

2: Cf. https://www.bpb.de/themen/rechtsextremismus/dossier-rechtsextremismus/516447/incels/ (retrieved 08.08.2025).

3: Cf. https://a-part-time-nihilist.quora.com/https-www-quora-com-Was-Friedrich-Nietzsche-an-incel-answer-Susanna-Viljanen (retrieved on 07.07.2025).

4: Cf. Racha Kirakosian, Intoxicated deprived of senses, P. 149.

5: Bf. v. 8/1882.

6: Aph 239.

7: Cf. P. 23.

8: No. 59; p. 120.

9: Martin Vogel, Apollinan and Dionysian, p. 294 f.

10: Nietzsche's disease, P. 57.

11: Bf. to Carl Gersdorff v. 26/5/1876.

12: For an excellent overview of Nietzsche's diverse relationships with women, see also the relevant monograph Forget the whip by Carol Diethe.

13: Apollinan and Dionysian, P. 295.

14: Brann, Nietzsche and the women, P. 175.

15: Cf. Bf. v. 11/4/1876.

16: Cf. Diethe, women, P. 56.

17: Cf. Joachim Radkau, Malwida von Meysenbug, P. 360.

18: Bf. v. 1/7/1877.

19: Bf. v. 2/6/1877.

20: Bf. v. 3/9/1877.

21: Cf. Brann, Nietzsche and the women, P. 151.

22: So Zarathustra spoke, From old and young women.

23: Cf. Diethe, women, p. 50 f.

24: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 9.

25: Cf. bird, Apollinan and Dionysian, P. 315.

26: Cf. Volz, Nietzsche's disease, P. 57.

27: Cf. Anja Schonlau, Syphilis in literature, P. 84.

28: See ibid., p. 101.

29: Cf. Tamás Tényi, The Madness of Dionysus. Nietzsche researcher Christian Niemeyer recently tried to rehabilitate the “syphilis thesis” (cf. Nietzsche's syphilis).