#

equality

Monumentality Issues. Nietzsche in Art After 1945

Thoughts on the Book Nietzsche Forever? by Barbara Straka II

Monumentality Issues. Nietzsche in Art After 1945

Thoughts on the Book Nietzsche Forever? by Barbara Straka II

Barbara Straka's newly published book Nietzsche Forever? explores the question of how Nietzsche is received in 20th century art, in particular that after 1945. But the reception of Nietzsche's reception raises the question of whether the philosopher's monumentality is lost sight of. Does this reveal a fundamental problem of our age with monumentality? In any case, starting from Nietzsche, Michael Meyer-Albert argues against Straka for a “post-monumental monumentality” as an alternative to aesthetic postmodernism. In the first part of the two-part series, he dedicated himself to her book, and now he is accentuating his opposite position.

Übermensch Hustling

Nietzsche Between Silicon Valley and New Right

Übermensch Hustling

Nietzsche Between Silicon Valley and New Right

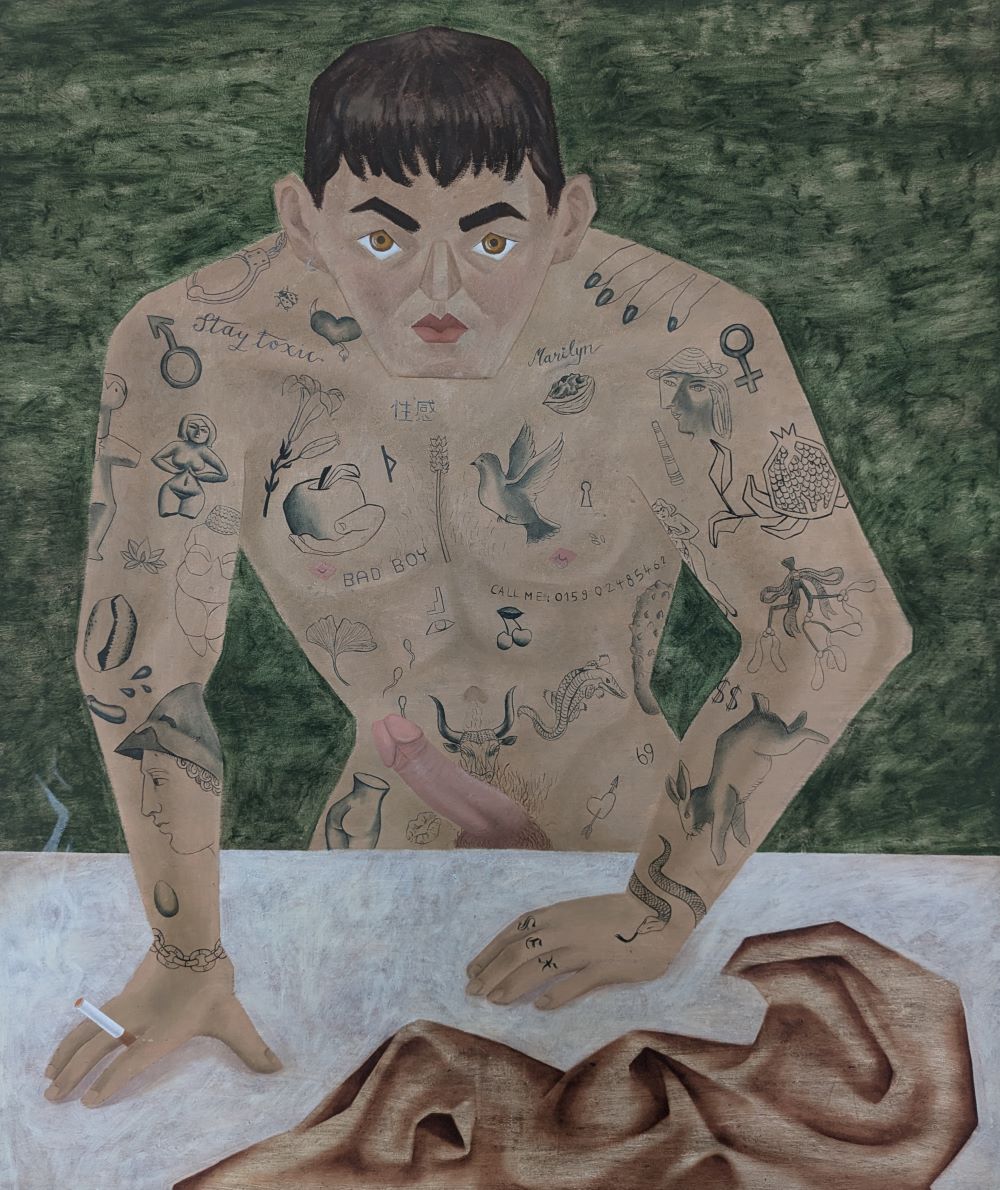

This essay, which we awarded first place in this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing (link), examines Nietzsche's question of the “barbarians” in a contemporary context and analyses how his philosophy is being politically exploited today. Against this background, the text shows how hustle culture, platform capitalism and neo-reactionary ideologies have been economizing the ”will to power“ and have become a new form of subtle barbarism: an internal decomposition of cultural depth through market logic, technocratic myths, and performative nihilism. Nietzsche's thinking, however, can be used precisely to describe these tendencies in their genealogy, to unmask their immanent nihilism, and to present an (over-)humane alternative to them.

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Individualism, even egoism, is frowned upon in all political, religious and social camps. They are attributed to liberalism and capitalism. Such people are not committed to others, are not involved politically or for the environment. They also do not respect a common understanding of the world and therefore behave irresponsibly. The Nietzschean is not impressed by such verdicts. She dances — not only!

Nietzsche and Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche and the Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche was repeatedly elevated to a figurehead by right-wing theorists and politicians. From Mussolini and Hitler to the AfD — Nietzsche is repeatedly seized when it comes to confronting modern society with a radical reactionary alternative. Nietzsche was particularly fascinating to intellectual right-wingers, such as authors like Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, who formed a cultural prelude to the advent of National Socialism in the 1920s, even though they later partially distanced themselves from it. People also often talk about the “Conservative Revolution”1.

What do these authors draw from Nietzsche and to what extent do they read him one-sidedly and overlook other potentials in his work? Our author Paul Stephan spoke about this with philosopher Robert Hugo Ziegler.

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

It is well known that Nietzsche had a hard time with women. His sexual orientation and activity are still riddled with mystery and speculation today. Time and again, this question inspired artists of both genders to create provocatively mocking representations. Can he possibly be described as an “incel”? As an involuntary bachelor, in the spirit of today's debate about the misogynistic “incel movement”? Christian Saehrendt explores this question and tries to shed light on Nietzsche's complicated relationship with the “second sex.”

Chameleon Nietzsche

The Failure of Nietzschean Materialism

Chameleon Nietzsche

The Failure of Nietzschean Materialism

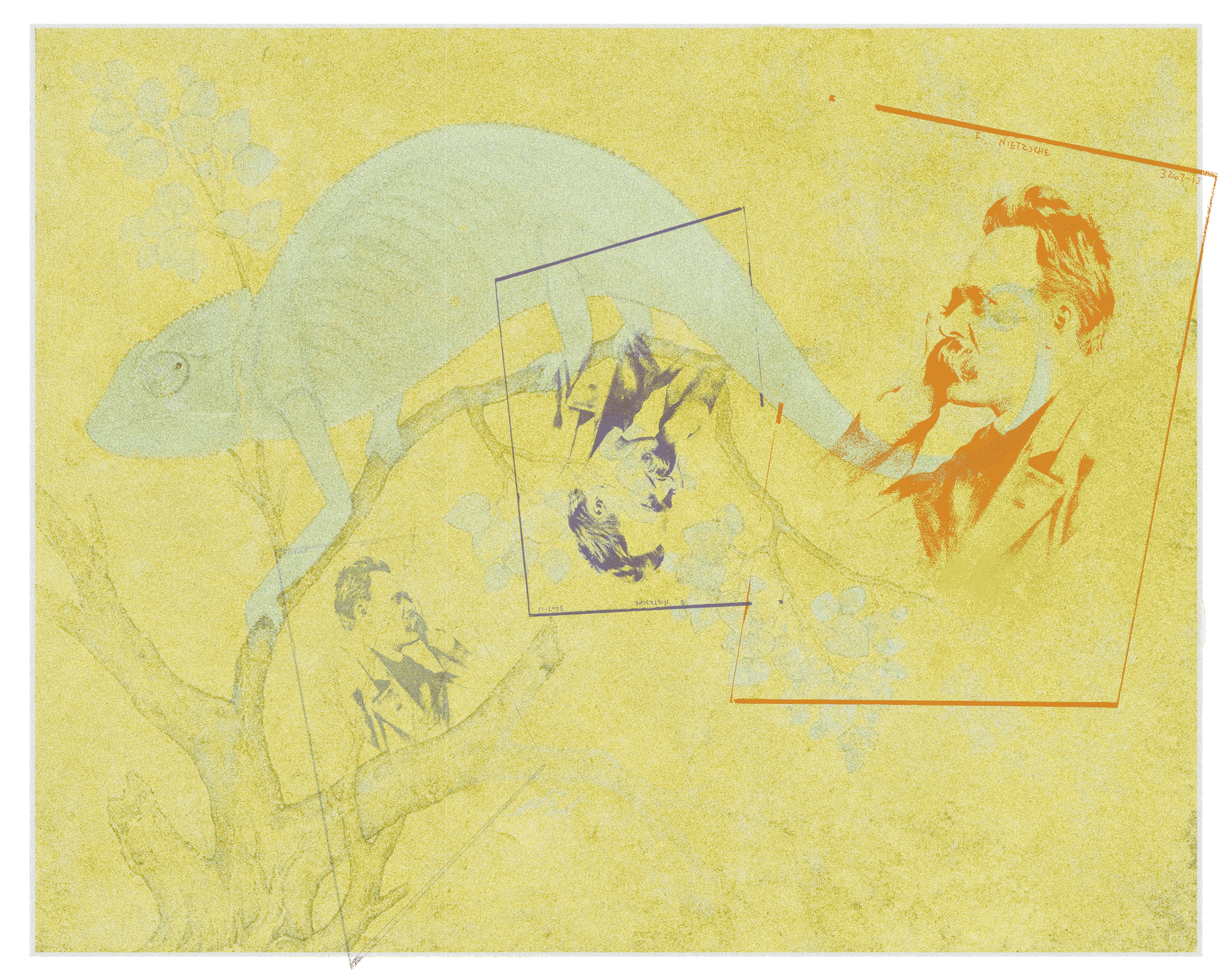

The connection between Marx(ism) and Nietzsche(anism) has repeatedly been a topic on our blog. To what extent can the ideas of arguably the most important theorist on the left and the philosophical chameleon, who was an avowed anti-socialist and anti-feminist and inspired Goebbels and Mussolini, among others, be meaningfully combined. While there have been repeated attempts at left-wing Nietzscheanism, Estella Walter's conclusion in this controversial thesis article is skeptical: The contrast between “historical-dialectical materialism” and Nietzsche's idea of will to power is too irreconcilable. Beyond his time diagnosis, his thinking only provides little emancipatory content.

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Strangers seem creepy to many. They immediately fear that these strangers will harm them. Many decent earners think that recipients of citizen benefits are lazy and therefore do not allow them to receive government support. To many educated people, illiterate people appear rude and simple-minded, with whom they therefore want as little as possible nothing to do with, whom they do not trust. Religious people are often afraid of atheists, who in turn are afraid of contact with religion. What you don't know often appears to be dangerous and you prematurely discount that. Such prejudices lead to rejection, which often solidifies to such an extent that counterarguments are no longer even heard. This is resentment that has existed for a long time, but which today makes consensus almost impossible in many political and social debates. This can degenerate into hate and contempt and then into violence whether between rich and poor, right and left, machos and feminists, abortion opponents and abortion advocates, vegetarians and meat-eaters. When one side prevails, it imposes its values on the other, and the resentment even becomes creative. In any case, it prevents you from making an effort to understand the other person. For Nietzsche, resentment has been driving the dispute over what is morally necessary for a long time.

“Resentment” is one of the key terms of Nietzsche's late work. The philosopher is referring to an internalized and solidified affect of revenge, which leads to the development of an overall negative approach to the world. Especially in On the genealogy of morality Nietzsche is trying to show that the entire European culture since the rise of Christianity has been based on this affect. Judaism and Christianity, in their hatred of aristocrats, propagated an ethics of the weak — in this act, resentment became creative. With a new creative ethic, Nietzsche now wants to contribute to a renewed revaluation of values in order to return to a life-affirming aristocratic ethic of the “strong.” In this article, Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann introduces Nietzsche's reflections on resentment and works out what makes the accusation of mutual resentment so popular to this day.

Taylor Swift — Superwoman or Last Man?

A Nietzschean Critique of the Most Successful Pop Star of Our Time

Taylor Swift — Superwoman or Last Man?

A Nietzschean Critique of the Most Successful Pop Star of Our Time

Taylor Swift is one of the most important “idols” of our time. Reason enough for our regular authors Henry Holland, Paul Stephan and Estella Walter to pick up on the Nietzschean “hammer” and get to grips with the hype a bit: Does Swift deserve the cult around her that goes down to philosophy? Is it grossly overrated? And what explains the discrepancy between appearance and reality, spectacle and life?

You can watch the entire unabridged conversation on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy YouTube channel (link).

Age-Old Rage

The birth of Modernity out of the Spirit of Resentment

Age-Old Rage

The birth of Modernity out of the Spirit of Resentment

“Resentment” is one of the guiding concepts of Nietzsche's philosophy and perhaps even its most effective. In his new book The cold rage. Resentment theory and practice (Marburg 2024, Büchner-Verlag), Jürgen Grosse argues that since the 18th century, more or less all political or social movements have been those of resentment. Our main author Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann has read it and presents major theses below.

“The Most Noble Adversary”

Daniel Tutt and Henry Holland in Dialogue

“The Most Noble Adversary”

Daniel Tutt and Henry Holland in Dialogue

After two previous contributions to Nietzsche in the Anglosphere For this blog, Henry Holland interviewed American thinker Daniel Tutt about his perspective on Nietzsche as the most important antagonist of the left. The discussion included Huey Newton, leader of the Black Panthers in the 1970s, and what his “parasitic” way of reading Nietzsche prompted him to read. An unedited and unabridged version of this interview, in original English, can be heard and watched on Tutt's YouTube channel (link).

What Does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

What Does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

Our regular author Christian Saehrendt reports in his contribution to the series “What does Nietzsche mean to me? “about how he discovered Nietzsche as a teenager and has regarded himself as a fan of the philosopher ever since — precisely because of his contrariness.