Monumentality Issues. Nietzsche in Art After 1945

Thoughts on the Book Nietzsche Forever? by Barbara Straka II

Monumentality Issues. Nietzsche in Art After 1945

Thoughts on the Book Nietzsche Forever? by Barbara Straka II

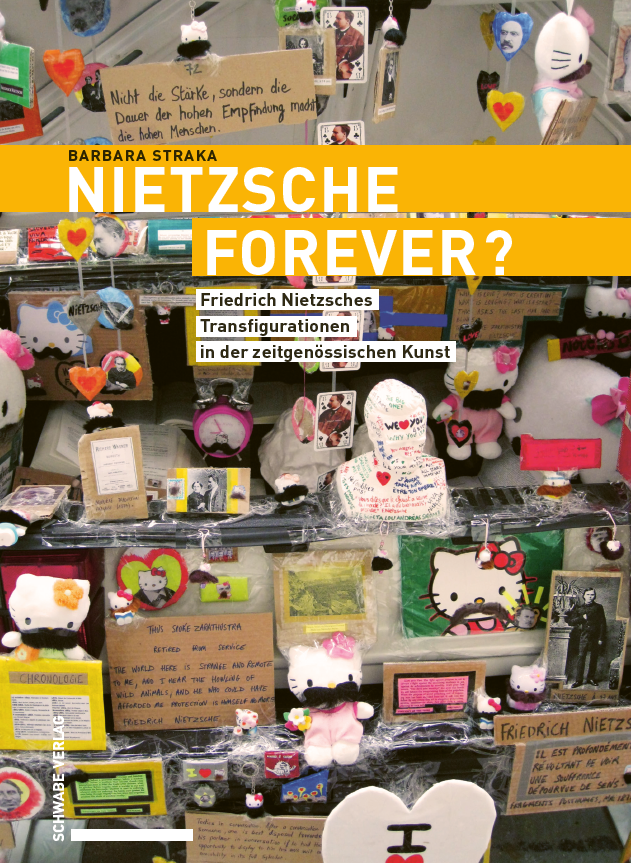

Barbara Straka's newly published book Nietzsche Forever? explores the question of how Nietzsche is received in 20th century art, in particular that after 1945. But the reception of Nietzsche's reception raises the question of whether the philosopher's monumentality is lost sight of. Does this reveal a fundamental problem of our age with monumentality? In any case, starting from Nietzsche, Michael Meyer-Albert argues against Straka for a “post-monumental monumentality” as an alternative to aesthetic postmodernism. In the first part of the two-part series, he dedicated himself to her book, and now he is accentuating his opposite position.

III. Horse Hug

Straka's observation that it was primarily certain details from Nietzsche's work and life that became decisive for art after 1945 gains particular significance for the philosophically interested reader. The gesture of hugging a horse is central to this. In January 1889, according to an anecdote, which probably happened one way or another, Nietzsche saw a coachman mistreating a horse in Turin. He ran to the horse, hugged it and thus protected it from the blows. From this scene, which caused quite a stir, Nietzsche was perceived as having a mental disorder and spent his life in nursing care.

Straka captures this moment in Nietzsche's life succinctly: “After the Turin Incident, the philosopher Nietzsche no longer existed.” (p. 517) The significance for Nietzsche's reception lies in the fact that his philosophy of affirmation of life, which sometimes turned into a metaphysics of will with social Darwinian features even before, but especially in his later thinking, often turned into a metaphysics of will with social Darwinian features. The truth of life prevailed over a philosophy of absolute victory. Straka sums up:

The “Turin Horse Hug” is a legend, but it is not suitable for making Nietzsche a myth again in contemporary art or stylizing it into a cult figure; it actually makes him a human in the first place because it depicts the fall of a delusional self-proclaimed god. She thus plays a key role within the themes and motifs of recent Nietzsche art. [...] [F] for posterity, Nietzsche is not a failure; his mental collapse in Turin did not set an end point, but a starting point for a new, empathetic view of person, life and work.1

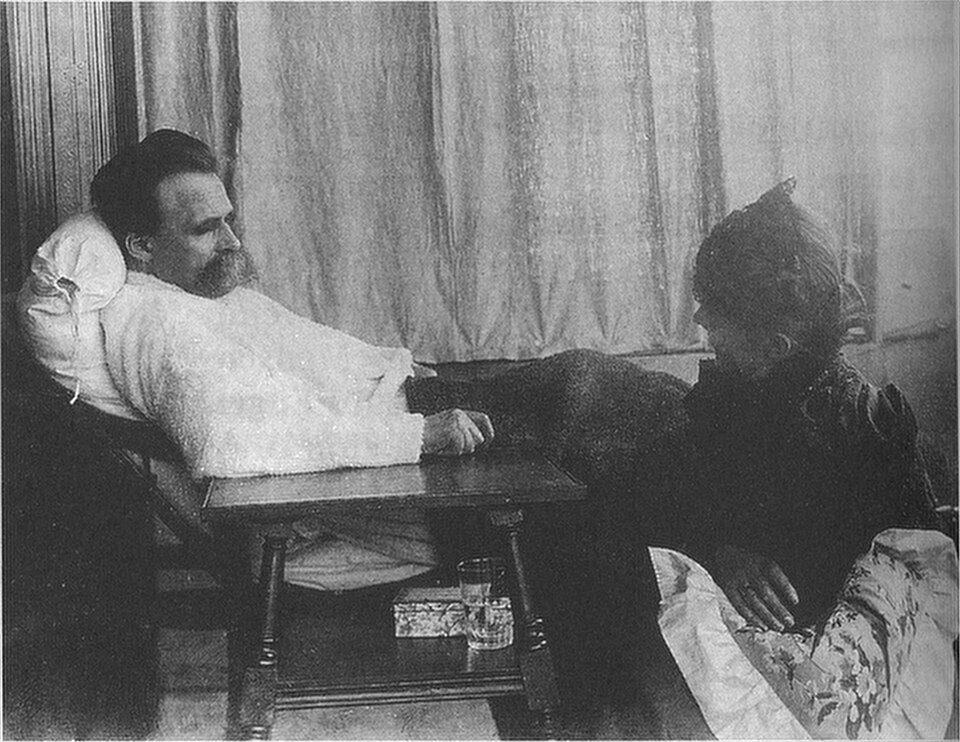

Nietzsche now appears no longer as a monster of creativity who embodied a precarious triumphalistic philosophy of life, but as a vulnerable thinker who suffered from massive health problems (such as cluster headaches) and was forced to travel constantly in search of tolerable and affordable places to stay socially placeless. Photographs taken by Hans Olde in 1899, which document Nietzsche's nursing case and which “have contributed significantly to a convincing characterization of the philosopher to this day” (p. 568), were decisive for the reception.

The gesture of hugging a horse implicitly refutes the extremist statements of late Nietzsche, who falsely substantiated the transfiguration of the truthful animal into an ontology of chaos, which then legitimizes lethal naturalism as a will to power. The sick Nietzsche is not the true Nietzsche, but the truer Nietzsche. The weakness of Nietzsche's painting, which emphasizes his failure in life, is, however, the concealment of the strong vitality that this life was ultimately about. Sensitive iconoclasm immediately deconstructs encouragement with the cult. For Straka, it borders on cynicism that the contemporary depictions of a vitalist Nietzsche no longer relate to Olde's paintings (see p. 664).

IV. A New Nietzsche Cult?

Where there was a cult, people should become: This is how the path Nietzsche left behind in art could be described. When receiving the reception of art, it is obvious that Nietzsche may have fallen victim to a cult for the second time. He was first over- and then under-monumentalized in the arts. Nietzsche becomes human as a sufferer, a sick person, a fragile person, and Nietzsche becomes a person in the manifold humanizations that appear most expressive in pop culture, but also dominates access to Nietzsche in more ambitious contemporary art. Straka affirms this trend:

The heroism, pathos and monumentalization that characterized the Nietzsche cult after 1900 have given way to differentiated representations of a contradictory, offensive, but also human, personal, even private Nietzsche who no longer fits on a memorial base.2

However, this anti-monumental tendency can not only be understood as a beneficial neutralization of excessive interpretations, as the “final phase of the deconstruction of the former cult image of Nietzsche” (p. 663), but it also bears the features of a new cult. It can be seen as a derivative of an iconoclastic cultural movement spanning the entire modern era. Everything old is brought before the court of reason. This gives the value of the new one the highest value. Culture as an imitation of excellence gives way to compulsive freedom, which can only believe in itself as an innovation and is self-referentially dynamic as a distance from competing innovation as innovative innovations. You imitate yourself in your worldless and world-poor innovation in order to stabilize yourself as a cult in the market of attention. You become a culture that imitates yourself because the imitation of past cultural greatness, which worked through reality resonance, is taboo. Committed to nonsense.

Four characteristics characterize modern traditional phobia in the field of art: It sacralizes firstly the spectacular excesses of subjective creativity — including Damien Hirsts For the Love of God (2007; link) or Wim Delvoyes Cloaca (2000; link) — who vie for attention, to the classical cultural dynamics of reverent imitation and careful variation, which wrestle within a decoration for inspiring emotionality, gives it secondly Meaning through billboard concepts, it creates thirdly Attention through the new power of exhibition as an attribution of quality and embodies it fourthly an informal morality that gains the “goodness” of works by simply revaluing the value of “degenerate art”:

A) Fuck it! Just express yourself!

The new cult of anti-monumentalism is evident as a sacralization of creativity in works that do not present a world, but only themselves as hypercreativity. Nietzsche's thinking can be heard here insofar as a legitimizing idea for self-referential spectacle creativity can be found in it. Nietzsche's “revaluation of values” is understood as a license to reject the “conventional” patterns of canonical works and to pursue a frivolous perspectivism in which maximum originality appears as a phenotype of creative vitality. The motto is: generating attention through excitement and no longer the traditional development of astonishing emotionality. One example of this is the leaves The Dark Child God, Transsilvannietzsche and DR. N. by Jonathan Meese (see p. 151), by whom Straka is delighted: Jonathan Meese succeeded in distorting Nietzsche to the point of recognition (see p. 153).

B) Readymade content

The reference to Nietzsche as the philosopher of the mask is once again becoming a mask in the context of contemporary art itself. The pop Nietzsche is explicit what the new art Nietzsche is usually implicit: aura markers for one's own products. Nietzsche serves as readymade content for content-free art. They outsource to him a depth of the works that the works themselves no longer own. The canonical authority of the works of which Mörike wrote is now over: “But what is beautiful, it seems blissful in himself.” Content is delegated to Nietzsche in order to evade the responsibility of the forms for the “sensual appearance of the idea” (Hegel). The works can only be “understood” as a “concept.” They become pure signs for which there is no language. Your concept says what they should mean. Her hypercreative hermeticism is deciphered by the hermeneutics of expressiveness without clarity.

Examples: Felix Dröse's drawings from the cycle Untitled (“I'm dead because I'm stupid, I'm stupid because I'm dead.”) from 1981 (see p. 614 ff.) show clumsy sketches made by the artist in the dark, thinking intensely of Nietzsche, according to his concept. Stephan Hubers Zitronstadel (originally: “Zarathustra im Zitronstadel”), from 2005 shows a wooden box quoting from “Also spoke Zarathustra” in the Allgäu dialect (see 464 f.; link).

C) “Exhibition Power” (Heiner Mühlmann)

Works that no longer display a world become works of art through the location where they are exhibited. The presentation in museums, in public spaces or even in a book about contemporary art gives the dignity of the highly cultural.3 The implicit competence of the aesthetic work gives way to the emotional state of the “exhibition trance” (Mühlmann), which refines pseudo-cultural water into highly cultural wine. The pedestal from which all monumentalist works are to be retrieved lives on hidden in the gesture of presentation. After the decorative ornament has been ennobled into “abstract art,” the museum is used as an installation by Casimir Malevich's4 Work concept for the white 3D square as a work of art naming work. Art is the power of the spatial effect. “The museum is no longer exhibiting anything. It turns itself off. ”5 In this exhibition, the mere aura of the exhibition results in meaningless, uninformative cultural imitation, which is called”Selfish cultural variant”6 (Mühlmann) occupies the valuable capacities of imitation, from which something could be learned. Sloterdijk adds to Mühlmann's observations:

The path of art follows the law of alienation, which proves the power of imitation precisely where imitation is most strongly denied: It leads from artists who imitate artists, to exhibitors who imitate exhibitors, to buyers who imitate buyers. From the motto L'art pour l'art Is the concept before our eyes The art system for the art system became.7

D) Entenatary art

The new cult of anti-monumentalism manifests a charge of meaning and value through morality. It is not the good that dominates, but the good. The aesthetic structure is charged with quality because it is in the tradition of what used to be “degenerate art.”8 A “framed ornament” (Mühlmann) can thus appear as anti-fascist “abstract art.” The truth of antinacian art is therefore the good that it stands for. There is no question of an in-depth response to realities. The absence of references to the work is reinforced externally through the rituals of reception. A moral view of art as a degenerate stabilizes it tribalistically. It sends harmony inwards, aggression outwards. Criticism of the lack of content is responded to in a maximally moral way by not responding to the objection, but by launching an automatic insinuation that, for example, brings criticism of contemporary works as mere “framed patterns” (Mühlmann) into the highly problematic tradition of fascist propaganda.

V. The Struggle for Monumentality

It is precisely this moralizing of aesthetics that motivates Straka's book to the extent that it contradicts Christian Saehrendt's views positioned; expressly at the end of her book in the acknowledgments (see p. 739). Sährendt, a regular author of this blog, speaks loudly in Trump's sometimes hard-to-bear tones for a remonumentalization of Nietzsche — “Make Nietzsche great again! “(see p. 585) —, gladly as a large monument above the Saale. Straka, on the other hand, defends himself against them with a more differentiated but also very affirmative view of the art world — probably as a deliberate provocation Cum grano salis — sounds and smells in Sährendt's statements, reflecting his polemical escalation in a way that is difficult to bear, even an update of the contempt of modern art as “degenerate” (see p. 598).

Perhaps this constellation could be used to gain an extended term for the understanding of reception? Is the opposition between Straka and Sährendt, insofar as he represents the point of view assumed by Straka to him in the first place, not about more than aesthetics? Does this particular confrontation over Nietzsche's legacy not also reflect the general rift that runs through the Western world and is embodied in a cultural struggle that is no longer just a cold one? Is there not the question in the background whether the modern struggle for recognition should emphasize justice in the sense of anti-monumentalist equal treatment or rather the monumentalist uniqueness in the sense of brilliance? Could Nietzsche possibly gain a comprehensive concept of monumentality that is ignored in this cultural struggle?

The question of how Nietzsche appears in art is a question of the form of relationship that is assumed with tradition. By deconstructing the monumentalist Nietzsche in the arts after 1945, the monumentalist is actually deconstructed as a form of reference to tradition.

Appropriately enough, Nietzsche himself wrote an essay that explores the question of the relationship to tradition. He distinguishes in his second Unexpected viewing with the title The benefits and disadvantages of history for life From 1874, three ways of dealing with history: One antiquarian Dealing that respectfully overlooks and wants to preserve the past; a monumentalist Dealing that strives for even greater things and instrumentalizes the past as motivation and role model; and a critical People who suffer from the past and want to emancipate themselves from it. Nietzsche primarily criticizes the dominance of antiquarian treatment of history in his time. Through this philosophically staged attitude by Hegel, contemporaries are brought into the position of viewers in a drama in which they themselves play a part. The belief that you are only a spectator of your own story demoralizes and creates cynicism.9

Nietzsches Untimely viewing Translated into the contemporary, shows a current overemphasis on the critical approach to tradition, but without suffering from it. It stabilizes itself in a cult of absolute innovation. The idea of canonical classicity as an admirable imitation model fails. Everything should be pushed off the base. There must be no superhumans and superpowers, because the shock of mastery and his works is too deep. There is no such positive connection to monumentality. As compensation, this shortcoming then creates a neo-monumentalism that bears the traits of areflexive, defiant self-affirmation and strives for a modernized size without being able to do it. The truth of anti-monumentalism in aesthetics is empathy for time and a sensitivity for its way of presentation. The truth of neomonumentalism is a critique of ignoring historical grandeur and a sense of the sublime. What is missing is well-tempered monumentality.

VI. Post-Monumental Monumentality

Perhaps, following a clue in Sloterdijk notebooks,10 Put forward the thesis that the sublime, which Nietzsche first located in art and then criticized in religion, was converted to the grandeur of the state and the military in the phase of its monumentalist reception. In the phase of anti-monumentalist reception, these forms of grandeur were criticized, but the sublime was thus ignored in the first place. What both phases so omit is the grandeur of evidence, which comes to the center of post-Wagnerian Nietzsche and allows post-metaphysical high notes in philosophy. What deserves the utmost seriousness, what is the most effective and can claim higher rank — even in the egalitarian states of the super-correct, hypersensitive, consensual zeitgeist — is the power of truth. God is dead, art is opiate, the state is bureaucracy and the military is a place of pre-modern heroic. But the truth is that the heart of modern grandeur beats. Paradoxically, this “sense of truth” (Sloterdijk) appears in Nietzsche as a discovery of the semblance necessary for life. Truth as a truth of illusion, which is intended to stimulate and protect, does not come with the old European pathos. It does not appear in the preaching or commanding apostle form, but as a therapeutic experiment with possible facilitations. The most serious can thus be understood as clarification, as relief and as an invigorating and motivating lie.

This decisive point of Nietzsche's concept of grandeur is also found in his second Unexpected viewing. Nietzsche puts forward the thesis that appearance as a constitutive aspect of life means a kind of minimal monumentality. Life requires the primacy of one's own over the foreign as a protective cocoon, a sealing atmosphere, an “enveloping delusion.”11, which limits and ignores the horizons of the incoming newcomer to such an extent that a positive self-image is stabilized as:

And this is a general law: every living person can only become healthy, strong and fertile within one horizon; if it is unable to draw a horizon around itself and in turn too selfish to include one's own gaze within a stranger, it taint or hastily seeps away at present doom.12

This cultural immune system of therapeutic hubris protects “the irreverent illusion in which everything that wants to live can live alone.”13. The truth of life is not neutral. It is the exact opposite of a perspective that wants to think of the truth as lack, alienation, robbery, exploitation. The pessimist Adorno is wrong: Wanting to think of the whole thing as untrue is untrue. There is a wrong life in the right one. History understood monumentally becomes a “remedy against resignation”14 and motivates people to become more lively.

In the following years, after turning away from Wagnerism, Nietzsche himself succeeded in uncovering perspectives that show an advanced idea of monumentality. According to this, the monumentality of modernity is to be seen as an “age of comparisons.”15 has to do cultural-psychological preparatory work for a cosmopolitan location within a global post-metaphysical ecumenism. This involves an evaluation of all cultures with regard to a new idea of noble vitality that distances itself from resentful retaliatory logics and from nihilistic lethargies, which can be imitated by future generations in an exemplary manner. Monumental about our time is the practising ritualization of civil, globally compatible monumentalism as an archive search and an attempt at construction. Nietzsche himself speaks of a cultural experiment that could satisfy any heroism.16 And he also mentions the attitude of a resentful relationship with tradition: “There are, of course, strange human bees who only ever know how to suck the bitterest and the most annoying out of the cup of all things; [...]” and at a “bee basket of malaise.”17 build.

In the “age of comparisons,” art has the task of co-constructing an exemplary minimal monumentalism — a bee basket of comfort — which, even in view of the task and the abysses of the course of the world, makes an affirmation of the situation appear plausible in a locally concentrated symbolism. It is important to find an expression for a hope that can be believed in. Transfiguration of all countries, unite! Art is thus in productive competition with religion and philosophy when working on global civil transfigurations of a life of not only economic prosperity. The categorical imperative of post-monumental monumentalism is: Act in such a way that the choice of cultural role models that you imitate and who educate you embodies the permanence of sustainable, creative and generous liberalism so much that your life can also become a possible inspiration for others.

VII. “Nietzsche on a Bike”

Straka's book contains several works that reveal a post-monumentalist monumentality. This shows that we have the successful works of art to make the existence of the art business even more bearable.

Mathieu Laca's painting is particularly noteworthy Nietzsche on a Bike from 2016 (see p. 665). It shows the philosopher wearing glowing sports shoes on a racing bike. He looks up at the viewer like someone who is absorbed by his performance — the indicated cube around the figure reinforces this impression — and his gaze oscillates between being watched by surprise and an appeal. If you want to project thoughts into this view, they could read: “Oh. What do you want? Get on your bike yourself. Make something out of yourself! “Nietzsche is thus exposed as a trainee who affirms life as an overcoming in a physiological way, 6,000 feet beyond Übernietzsche and TINY-Nietzsche.

The impression of Nietzsche in Laca's painting can also be transferred to other areas of life. After the mobilized masses of red-brown and brown-red professional revolutionaries of the 20th century, for whom the struggle continues, come the athletized masses who, infected by sport, achieve brilliant achievements.18 The charism of the millennial empires and world revolutions is losing its luster. The betterment of the world begins in private life as a search for lost magnificence. Make yourself great again and again. In the spirit of Nietzsche: Seek disciplines and cultivate rituals that weaken the grumpy desire for retaliation because they do not interpret the empty hours as “abandonment of being” (Heidegger) and alienation. The time allows studies that are dedicated to the admirable, that invites imitation and that sparks their own success story of brilliant monumentality. As an example, Nietzsche's broken monumentality motivates people to set life up monumentally. His life rises into the modern age as a monument to a “resolution to serve life” (Thomas Mann). Because the power of the great that once was is still ongoing, we have the space to become more than we are. This enables pride that radiates jovial generosity and becomes immune from projecting feelings of grandeur into excessive imperial desire. Some victories and defeats are no longer necessary. The story is over. The fight is no longer going on. The training starts.

Article Image

Mitchell Nolte: The Turin Horse (2019; spring) (Used with permission by the artist.)

Sources

Mühlmann, Heiner: countdown. Vienna & New York 2008.

Sloterdijk, Peter: You must change your life. Frankfurt am Main 2009.

Ders. : Lines and days III. Notes 2013-2016. Berlin 2023.

Straka, Barbara: Nietzsche Forever? Friedrich Nietzsche's Transfigurations in contemporary art. Basel 2025.

Footnotes

1: p. 548 f.

2: P. 610.

3: In this regard, see Mühlmann, countdown, p. 91 ff.

4: Editor's note: The Eastern European artist Kasimir Severinovich Malevich (1879—1935) is regarded with his painting The black square (1915) as the progenitor of aesthetic modernism.

5: Ibid., p. 74.

6: “Self-related cultural variant.”

7: Sloterdijk, You must change your life, P. 689.

8: Cf. Mühlmann, Countdown, p. 63 ff.

9: Cf. On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life Paragraph 8

10: Cf. Sloterdijk, Lines and days III, p. 239 f.

11:The benefits and disadvantages of history for life, paragraph 7.

12: The benefits and disadvantages of history for life, Paragraph 1.

13: On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life Paragraph 7.

14: The benefits and disadvantages of history for life, paragraph 2.

15: Human, all-too-human I, Aph 23.

16: Cf. The happy science Aph 7.

17: Human, All Too Human, II, Mixed Opinions and Sayings, Aph 179.

18: Sloterdijk instructively pointed this out — cf. You must change your life, p. 133 ff. — that with the appearance of the “athlete” type since the reinstatement of the Olympic Games in 1896, a rebirth of antiquity in the passion for sport succeeded en masse. From sport, the impulse of the Renaissance as a broad-based force forms wide sections of the population.