“Smooth ice.

A paradise.

For the

who knows how to dance well!”1

Nietzsche and Techno

Nietzsche and Techno

Nietzsche and Techno

“Techno” — the show of the same name at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, with traveling exhibitions by the Goethe-Institut and publications in German-speaking countries is currently honoring a once-subcultural movement that became a mass phenomenon in the 1990s with the Berlin Love Parade and continues to live on in Zurich's Street Parade today. Did techno offer (or offer) the Dionysian cultural experience that Nietzsche celebrated in his writings? Would Nietzsche have been a raver?

Behind him, above him, around him:

The sound forces had now risen up very big, these huge devices that thundered into each other in him,

superhuman size.

He looked up, nodded and felt thought of the bum-bum-bum of the beat.

And the big bumbum said:

One one one

And one and one and —

One one one

and —

Horny horny horny horny awesome!2

Nietzsche had programmatically in the Birth of Tragedy The intoxicating vital Dionysian and the aesthetically contemplative Apollinian presented as the two basic antagonistic principles of human culture. In the preface, he answers the question: “What is Dionysian? “: It was “that madness from which tragic and comic art grew,” it was the “endemic delights, visions and hallucinations that had been transmitted to entire communities, entire cult gatherings” of the ancient Greeks.3 And elsewhere it says: “In order for there to be art, so that there is some aesthetic doing and looking, there is a physiological precondition for this: The intoxication [...] above all the intoxication of sexual stimulation [...], the intoxication of the festival, the competition [...] the intoxication of the will. ”4 According to Nietzsche, intoxication allowed (over) civilized people to return to an archaic form of existence: “With alcohol and hashish, you return to the stages of culture that you have overcome. ”5 At another point in the abandoned fragments, he literally demands “a booze next to every shop. ”6 In any case, Nietzsche sees the Dionysian state as the origin of all culture. For the Greeks, however, it was only synthesis and constant interplay with Apollonian culture that led to the flourishing of civilization. Apollonian art describes Nietzsche as the achievement of individuals who, through analysis and imitation, create works that were inspired by lucid dream images. Clarity of thought, formation of work, separation from nature and isolation of the artistic personality represent a visually influenced Apollinan culture, while in Dionysian culture, union with fellow human beings and with nature dominates, with the help of intoxication, music and dance.

It was the same night after the parade, and while dancing I realized that I could no longer tell which effect of which drug was working and was completely okay with this state of affairs. The music took me

on...7

Dionysian and Apolonian: No Nietzsche inventions

Archaeological experts and Romantic spokesmen were enthusiastic about Dionysus in the early 19th century. Friedrich Schlegel is considered the discoverer of this “cult”; he glorified Dionysus as the god of joy, abundance and liberation. Schelling contrasts Dionysian and Apollinian early on, in a similar form with Nietzsche's mentor Friedrich Ritschl in 1831. In addition, the Basel antiquarian Johann Jakob Bachofen in 1861 uses the contrasting terms telluric and Uranian or can be determined in Apollinan and Dionysian terms.8 Nietzsche has therefore taken up an existing figure of thought and developed it further with a view to Richard Wagner's work. With Wagner, too, the contrasts appeared in Apollinan and Dionysian before the publication of the Birth of Tragedy , and later there was a dispute between the Nietzsche Archive and House of Wahnfried over the question of which of the two antagonists had brought these terms into the debate first. Cosima later wrote to Chamberlain in this context that Nietzsche “doesn't have a drop of his own blood, just a strange gift of appropriation. ”9 In fact, the main idea is Birth of Tragedy in Wagner's script The art and the revolution from 1849: In order to create the drama, the highest work of art, the poet, who was as enthusiastic about Apollo as he was about Dionysus, would have to unite all genres of art.

Orgies only in theory, the cult of Dionysus as compensation — Nietzsche's lifestyle

Nietzsche is not only (or possibly only marginally) interested in Dionysus's orgiastic activities, but above all in his ability to endure suffering.: “Saying yes to life even in its strangest and hardest problems; the will to live, becoming happy in the sacrifice of his highest types of his own inexhaustibility — That I called it Dionysian. ”10 Living yes also meant saying yes to a painful life. After all, Nietzsche had a number of reasons for this: in addition to illness, loneliness and lack of social recognition.

During his time in Bonn, he neither enthusiastically attended the beer evenings of the Franconia brotherhood, nor did he enjoy the Cologne Carnival; alcohol and tobacco were not his thing. He may have experimented with drugs, i.e. with “medicines” recognized at the time, but more likely to alleviate his symptoms and less to specifically induce a festive state of intoxication. Outwardly, he valued bourgeois dignified clothing, which was considered old-fashioned even in Basel; he groped his way through the rocky high mountains with a delicate walking stick and elegant urban footwear. For him, the celebrating Dionysus remained a theoretical force, an ideal on paper whose excesses he did not even attempt to relive. Nietzsche was the absolute opposite of an exhilarating and sensually enjoying person: “In the image of Dionysus, Nietzsche redeems his unlived life, his encapsulated vitality. That will be his motto Live dangerously especially sublimated as Think dangerously enforced. ”11

The music picked me up... Suddenly, some faces around me felt pretty broken and fucked up, and I immediately thought: Hard soup, you look so broken now. I rummaged into my pockets, took something right away, in exchange for overly accurate observations or even any ridiculous thoughts.12

Techno as a historical phenomenon

Originally developed in the 1970s and 80s by German electronic bands such as Kraftwerk and African-American DJs in Detroit, the genre of music can be characterized by the synthesis and development of various styles of electronic dance music (house, synth pop, EBM, Detroit techno) and flourished over the 1990s. On the one hand, this gave rise to numerous sub-cultural subspecies, on the other hand, a mainstream techno was produced that delighted the masses at open-plan discos and at folk festivals, and was sometimes referred to as “fairground techno.” What was new about this movement was gathering and dancing in public or in improvised, sometimes quite remote places on urban wastelands or in nature. Parades (“parades”) with mobile music systems took on gigantic proportions in some cases, festivals (“raves”) could last several nights and days. The English verb “to rave” means “to romp” and has historically been used in the religious context of “shakers.” They had been a religious group in North America that had split off from the Pietist Quakers and practiced emphatic dance and song in church services. Some Methodist communities also celebrated such services, sometimes with heavy alcohol consumption. Church critics of these ecstatic gatherings in the 19th century invented the derogatory word “rave” for them.13 As a result, the term was given a new positive meaning in the 1980s.

Synthetic drugs such as ecstasy or LSD spread in the 1980s and 90s and enabled ravers to now dance for nights and days and to experience a “party crowd” thrown together by chance and constantly fluctuating as a deeply connected community. What was characteristic and new at the time was that techno was open to all dancers, and that there was neither dress code nor compulsion to dance as a couple, which is why rave culture was regarded as an agreement between free, pleasure-oriented individuals who unite to form temporary festive communities. Through drugs, lighting effects and the hypnotic effect of monotonous music, they can enter a trance-like state in which the limits of their self-consciousness are exceeded. At the Love Parade or at Club Tresor in Berlin, exactly the scenes that Nietzsche in the Birth of Tragedy enthusiastically described as conditions in which the “breaking of the Principii Individuationis experienced” with “blissful rapture”, through the use of “narcotic drinks” or the “pleasurable approach of spring that permeates all nature. ”14 Even in publications on techno from the 1990s, Nietzsche and the term Dionysian were associated with the new music and lifestyle. “The Dionysian escapism of techno is difficult to reconcile with conservative values,” Claus Bachor, for example, wrote in his book in 1995 techno.15 Techno was also seen from the point of view of healing and necessary self-love in a disoriented and rapidly technologically developing society. In a publication about the “Generation XTC,” Nietzsche was cited for this: “The techno-narcissist works with a skill that Nietzsche once called healthy and healthy love in Zarathustra. ”16 The novel hedonistic, individualistic dance culture and the opening up of the former socialist countries of Eastern and Central Europe led to the perception of techno as a “soundtrack of freedom” and an exhilarating “posthistoire,” i.e. an era “after history.”17 Clubs like the Berliner Tresor (no longer at its eponymous historic location since 2007) appeared back then as places where the limits of time and space were abolished in an ecstatic eternity of uninterrupted beats and bass and where visions from the subconscious mind expanded the view.18 In the meantime, we have arrived at the post-history and know that the story has continued “after the story.” The illusion of timelessness, however, still lives on today at many techno parties and raves.

The accompanying texts for the Zurich “Techno” exhibition explain that because techno does not require a fixed sequence of steps and no binding dance style, “the range of expressive options among dancers is particularly wide.” However, when you look at the dance scenes in the exhibition videos soberly, you get the impression of stereotypical movement patterns and unimaginative redundancy. It is by no means imaginatively “performed”, but often, also due to tightness on the dance floor, the body weight is simply shifted from one foot to the other. This is the image of mass swaying or trotting around, holding beer bottles and mobile phones in the hands, or being rhythmically stabbed in the air with the index finger from time to time. The latter is also the highest form of gestural interaction with the DJ, who in most cases helms himself with headphones and baseball cap, bends over his mixer and makes little eye contact with the audience. Viewed from the outside, and with a museum time gap of over thirty years, many 1990s techno parties and parades appear uninspired, strangely lifeless and uninviting, so that the Dionysian character of these events appears somewhat far-fetched to the sober observer. But it may be that the celebrators felt differently, i.e. more intensely and ecstatically.

When something receives museum ordinations, it is usually very valuable, very unusual — or very old, if not dead already; extinct, petrified and archaeologically relevant. Regardless of the fact that a lively techno culture still exists selectively and locally, the historical approach to techno does not bode well for a future Dionysian culture. Current news about club deaths in former European party cities and about changing nightlife habits of younger generations doesn't fit the picture nicely.

But even more absurd and broken than any drug abuse was, of course, general abstinence... not taking any drugs, on principle, is absolutely the most effective thing, definitely.19

During the Covid years, the impression could be created that intoxication as a social and therefore collective cultural event had no future, because digital-virtual cultural experience would become the new norm for reasons of infection prophylaxis. In this scenario, we would have been dealing primarily with an image-based, at best immersive, digital cultural life. In Nietzsche's diction, the Apollonian element would completely dominate: “The Apollonian intoxication keeps the eye excited in particular, in the Dionysian state, on the other hand, the entire affect system is excited and amplified.” But this is “the actual Dionysian normal state: that the human being immediately imitates and represents everything he feels in his body. ”20

Even though there was a revival of live culture, concerts, club nights and festivals in the post-Covid phase, a long-term trend towards disembodying cultural experiences is obvious. In the future, a good number of cultural events will take place online and in virtual worlds. From today's perspective, it still seems questionable whether experiences similar to those in a lively party crowd or in a mosh pit, the wild dance area at metal or punk concerts, usually right in front of the stage, are possible (or simulated). But perhaps one day the desire for Dionysian unification is just a distant memory, a historical phenomenon presented to inquisitive nerds and white-haired nostalgics in dusty museums and cultural-historical publications. Although Nietzsche personally shied away from the convivial, sensual intoxication and probably never experienced it, he saw it as the basis of all art and all cultural highlights. In the Birth of Tragedy He suggests how essential the interplay between rational isolation and intoxicating unification is for the human psyche:

Under the magic of Dionysian, not only is the bond between man and man reunited, but also the alienated, hostile or subjugated nature is once again celebrating its festival of reconciliation with its prodigal son, the human being.21

With that in mind: Let's get intoxicated!

Exhibition notice:

techno. Zurich State Museum, until August 17, 2025

https://www.landesmuseum.ch/techno

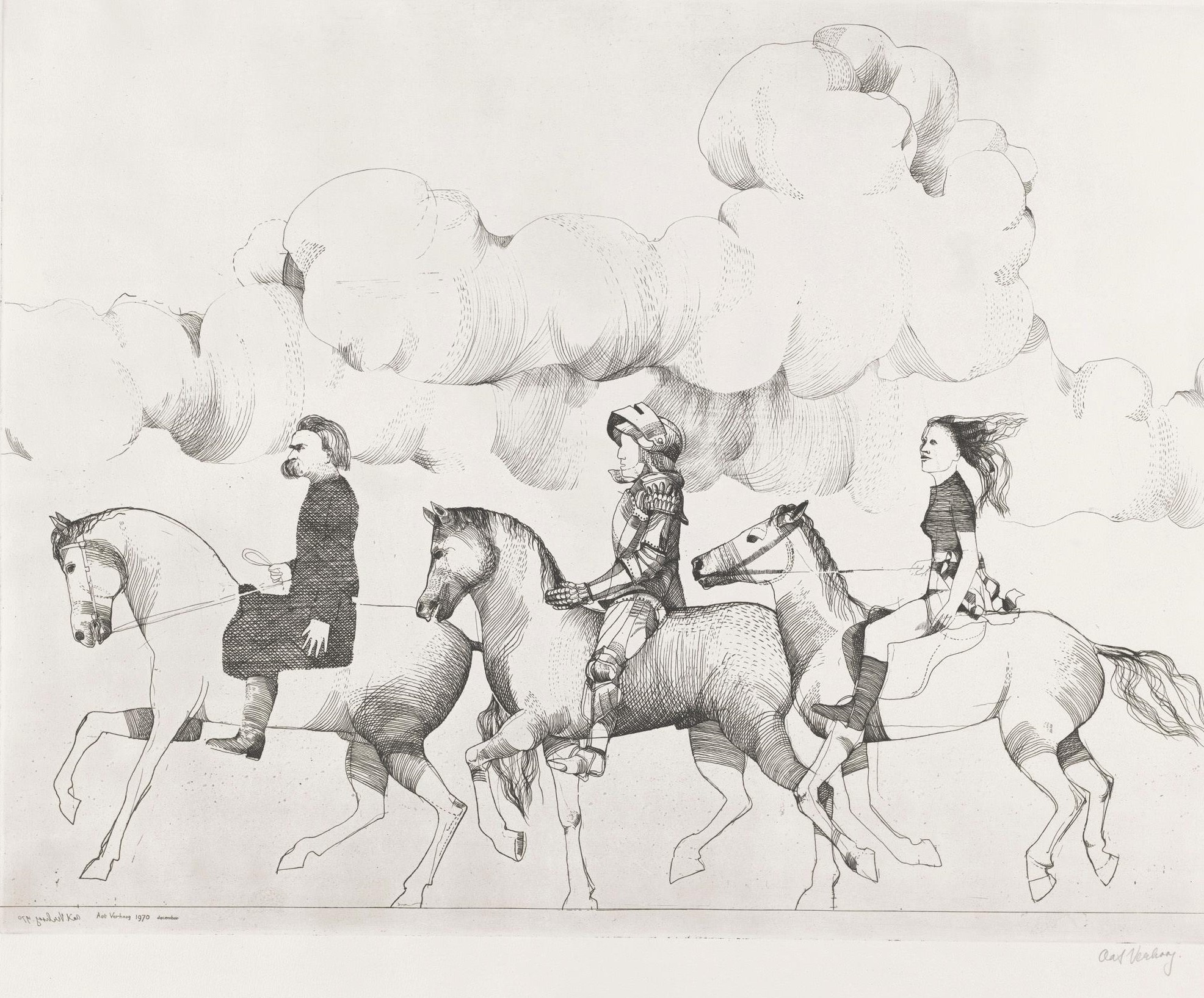

Article image: Nietzsche techno playlist on YouTube (link) (screenshot)

sources

Bachor, Claus: techno. Zurich 1995.

Balzer, Jens: No Limit The nineties — the decade of freedom. Berlin 2023.

Böpple, Friedhelm: Generation XTC. Techno and ecstasy, Berlin 1996.

Carlson, Anni: The myth as a mask of Friedrich Nietzsche. In: Germanic-Romanesque monthly 39 (1958), PP. 388—401.

Götz, Rainald: Rave. Frankfurt a. M. 2001, p. 18 f.

Kirakosian, Racha: Intoxicates deprived of senses. A story of ecstasy, Berlin 2025.

Stephen, Paul: Boredom in perpetual excess. Nietzsche, Intoxication and Contemporary Culture. In: Dominik Becher (ed.): Controversial thinking — Friedrich Nietzsche in philosophy and pop culture. Leipzig 2019, pp. 217—250.

Vogel, Martin: Apollinan and Dionysian. Story of a brilliant mistake. Regensburg 1966.

Wagner, Cosima & Houston Stewart Chamberlain: Exchange of letters 1888-1908. Leipzig 1934.

footnotes

1: The happy science, Joke, cunning and revenge, 13.

2: Rainald Götz, Rave, p. 18 f.

3: The birth of tragedy, an attempt at self-criticism, 4.

4: Götzen-Dämmerung, Journeys of an Out-of-Date, 8.

5: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 11 [85].

6: Subsequent fragments No. 1888 20 [12].

7: Götz, Rave, P. 180.

8: Cf. Martin Vogel, Apollinan and Dionysian, p. 95 ff.

9: Houston Stewart Chamberlain & Cosima Wagner, Exchange of letters 1888-1908, p. 350 (letter dated 15/9/1893).

10: Ecce Homo, Birth of Tragedy 3.

11: Anni Carlson, The myth as a mask of Friedrich Nietzsche, p. 393. (Editor's note: On this aspect, see also Natalie Schulte's corresponding interpretation of Nietzsche's request on this blog [link]).

12: Götz, Rave, P. 180.

13: Cf. Racha Kirakosian, Intoxicated deprived of senses, P. 232.

14: The birth of tragedy, paragraph 1.

15: Claus Bachor, techno, P. 46.

16: Friedhelm Böpple, Generation XTC, p. 193. What is meant is a passage from the third book of the Zarathustra (From the spirit of gravity, 2).

17: Cf. Jens Balzer, No Limit, p. 55 f.

18: For a Nietzschean analysis of techno using the Dionysian concept, see also Paul Stephan, Boredom in perpetual excess.1

19: Götz, Rave, P. 189.