Stuck Between the Monsters and the Depths

Wanderings Through Modern Nihilism in the Footsteps of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard — Part 2

Stuck Between the Monsters and the Depths

Wanderings Through Modern Nihilism in the Footsteps of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard — Part 2

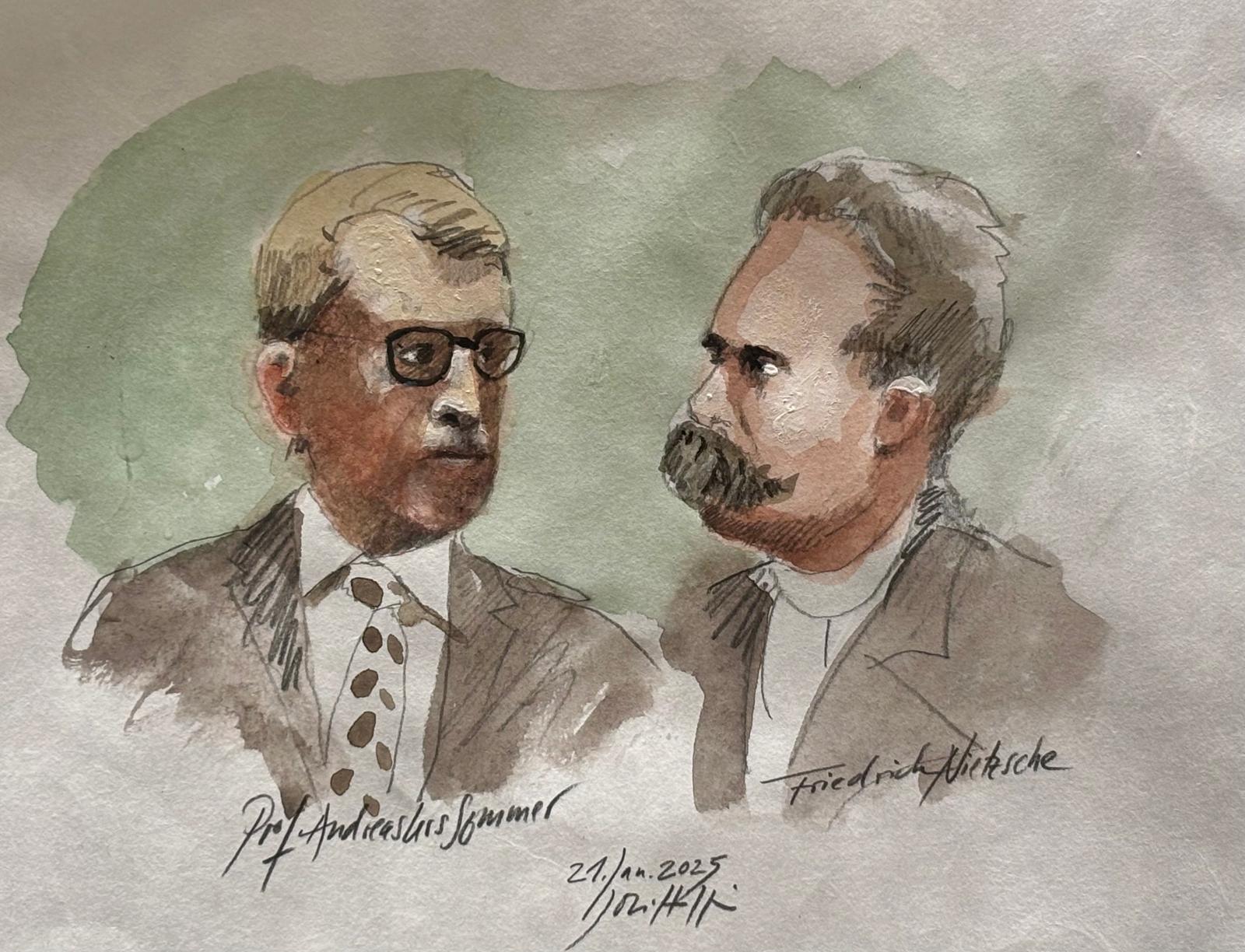

In this two-part essay, Paul Stephan examines how Nietzsche uses the wanderer as a personification of modern nihilism. After he is in the first part (link) focused on the general cultural significance of movement metaphors and the metaphor of wandering in Nietzsche's important brother in spirit, the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, it will now primarily be about Nietzsche himself.

III. From Jutland to Engadin

It is not surprising that similar descriptions can also be found in Nietzsche as a “seismograph” (Ernst Jünger) of the trials and tribulations of the modern soul, and in doing so he repeatedly refers to the metaphor of wandering. Even though he never read it, the stateless pastor's son described modern nihilism in a similarly drastic way as the failed Danish parish candidate. It is only with the way out that things are less easy for the self-proclaimed “Antichrist.”

“Wandering”, which previously appeared only sporadically as a metaphor for Nietzsche, has its first prominent appearance in the second encore to Human, all-too-human, The Wanderer and His Shadow, published in 1880. Nietzsche later describes this work as the expression of a fundamental crisis — “This was my minimum: “The Wanderer and His Shadow” was created during it. Undoubtedly, I knew how to use shadows back then...”1 —, which, however, at the same time his “recovery”, his “return to me”2 I ushered in. For him, “wandering” becomes a metaphor of an initially purely negative liberation from the familiar:

“Better to die than here Live” — this is what the commanding voice and seduction sound like: and this “here”, this “home” is everything she had loved up to that point! A sudden terror and suspicion of what she loved, a flash of contempt for what was called her “duty,” a seditious, arbitrary, volcanically upsetting desire for wandering, strangers, alienation, cold, disillusionment, icing, a hatred of love, perhaps a temple-abusing grip and gaze reverse, to where she worshipped and loved until then, perhaps an ardor of shame about what she just did, and a rejoicing at the same time, that She did it, a drunken inner exulting shiver in which a victory is revealed — a victory? About what? about whom? A puzzling questionable victory, but the first victory anyway: — such bad and painful things are part of the story of the great detachment. It is at the same time a disease that can destroy people, this first burst of strength and will for self-determination, self-appreciation, this will to free Will [.]3

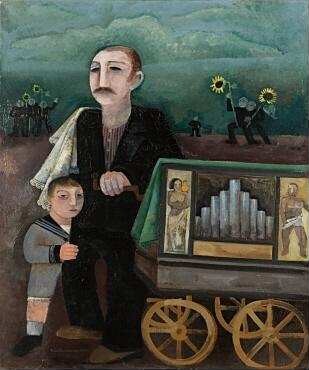

It is therefore not an easy triumph over the traditional, but with wandering, you are simultaneously entering the zone of danger and uncertainty. There is a risk of self-loss, which is perhaps even more terrible than the old captivity; a fundamental disorientation that would later give Nietzsche the name “nihilism.” Nietzsche will repeatedly describe this danger — his “shadow” — as his own danger, the abyss with which he constantly confronts and which threatens to swallow him up again and again. The hike is sometimes more positive than an adventure trip,4 but at the same time repeatedly described as a risk, as a “highly dangerous [] glacier and polar ocean migration”5, which threatens to lead the wanderer to nowhere; also a kind of way of the cross, but without redemption in the end.

Nietzsche shares with Rousseau a preference for the Swiss Alps, but this is about a completely different type of hiking, also a completely different kind of experience of nature. Even though you can't exactly imagine Nietzsche as a mountaineer — he was more of a walker who marveled at the peaks from the valley — the thinker comes forward to them at the risk of freezing to death. It is not contemplative rest from the misfortunes of civilization, but precisely the intensification of its restlessness and alienation that Nietzsche undertakes:

Or perhaps the entire modern historiography showed a more life-certain, more ideally certain attitude? Your primary claim is now mirrors to be; she rejects all teleology; she doesn't want to “prove” anything anymore; she disdains playing the judge and has her good taste in it — she says as little as she says no, she states that she “describes”... All of this is ascetic to a high degree; but at the same time it is to an even higher degree nihilistic, don't be mistaken about that! You see a sad, hard but determined look — an eye that Look outHow a lonely North Pole rider looks out (perhaps not to look in? so as not to look back? ...) There is snow here, life has stopped here; the last crows that make noise here are called “What for? ”, “For free! ”, “Nada! “— nothing thrives and grows here anymore, at most Petersburg metapolitics and Tolstoian “compassion.” But as far as that other type of historian is concerned, a perhaps even more “modern” kind, a pleasurable, voluptuous kind who is just as fond of life as with the ascetic ideal, who uses the word “artist” as a glove and has today leased the praise of contemplation completely and completely for itself: Oh what thirst do these sweet witches themselves still arouse for ascetics and winter landscapes! No! The devil may get these “contemplative” people! How much more would I like to wander through the darkest gray cold fog with those historical nihilists!6

Nietzsche is well aware of the high price of this heroism. That is what is perhaps one of his most famous poems, The free spirit:

The crows scream

And they fly to the city:

It will snow soon —

Probably the one who still has — a home now!

Now you're staring.”

Look backwards oh! How long ago!

What are you fool

Into the world before winter — escaped?

The world — a Thor

To a thousand deserts dumb and cold!

Who lost that

What you lose doesn't stop anywhere.

Now you're pale. '

Cursed to winter wandering,

Equal to smoke.”

Who is always looking for Kärtern Skies.

Fly, bird, snore

Your song in desert bird sound! —

Hideaway, you fool

Your bleeding heart in ice and derision!

The crows scream

And they fly to the city:

It's going to snow soon.”

Woe to him who has no home!7

At least that's the first section of the poem. But Nietzsche adds almost defiantly immediately afterwards:

That God is merciful!

The Meant I longed to go back

In's German Warm‚

Into dull German house luck!

My friend, what's here

Hinders and holds me back is your Reason'

Compassion with thee!

Compassion with German queer sense! (Ibid.)

It must So keep moving forward. Nietzsche also envisions his personal superman Zarathustra as such an eternal wanderer. The first speech of the third book is with The Wanderer and there the Prophet speaks “to his heart” i.e.: “I am a hiker and a mountaineer [...], I don't love the plains and it seems I can't sit still for long”8. Migration as a process of permanently overcoming ever new peaks, which must ultimately result in complete self-overcoming:

But you, O Zarathustra, wanted to look at the reason and background of all things: so you must rise above yourself — up, up, until you also still have your stars under You have!

Yes! Looking down at myself and still looking at my stars: that would first be called mine summitsThat was left to me as my last Summit! (Ibid.)

But doesn't that mean questioning the ideal of hiking yourself? Does the migration to its highest “peak” then cancel itself out and reach a dead end? The myth of the “eternal return” should probably fix it at the end of the third book, insofar as the eternal wandering person affirms himself as an eternally wandering person.

But even after that, doubts remain as to whether this self-affirmation is really seamless; in other words, modern humans can truly identify with their fate. In the fourth book, Zarathustra again meets his shadow. And he laments his fate in very similar words to Nietzsche in his unpublished poem:

I am a hiker who has already gone after your heels a lot: always on the go, but without a destination, even without a home: that is, I really lack little about the eternal Jew, unless I am not a Jew forever, nor am I a Jew.

How? Do I always have to be on the go? Whirled, restless, driven away by every wind? Oh earth, you were too round for me!

I was already sitting on every surface, tired dust and falling asleep on mirrors and window panes: Everything takes from me, nothing gives, I get thin — I almost resemble a shadow.

But I flew after you, O Zarathustra, for the longest time, and, if I hid myself from you, I was your best shadow: wherever you sat, I sat too.

I've dealt with you in the farthest, coldest worlds, like a ghost that voluntarily walks over winter roofs and snow.

With you I strove to every forbidden, worst, farthest: and if there is anything virtue about me, it is that I was not afraid of any prohibition.

With you I broke what my heart ever adored, I threw over all landmarks and images, I pursued the most dangerous wishes — truly, I once overcame every crime.

With you, I lost faith in words and values and big names. When the devil molts his skin, doesn't his name also fall off? Because he is also skin. The devil himself may be — skin.

“Nothing is true, everything is permitted”: I said to myself. I plunged into the coldest water with my head and heart. Oh, how often did I stand there naked as a red crab!

Ah, where did all the good and all shame and all faith in the good guys come to me! Ah, where is that false innocence that I once had, the innocence of the good guys and their noble lies!

Too often, indeed, I followed the truth close to my foot: that's when it kicked me in front of my head. Sometimes I thought I was lying, and look! That's when I met — the truth.

Too much clarified for me: now it's none of my business anymore. There is nothing alive that I love anymore — how should I still love myself?

“Live as I please, or not live at all”: that is how I want it, that is also what the Most Holy One wants. But woe! How do I still — feel like it?

Habe me — another destination? A port after my Sail is running?

A good wind? Oh, but who knows where He drives, he also knows which wind is good and his wind.

What was left behind for me? A heart tired and cheeky; an unstable will; fluttering wings; a broken backbone.

This search for my Home: Oh Zarathustra, do you know that this search was my Visitation, it eats me up.

“Where is — my Home? “After that I asked and searched and I did not find that. Oh eternal everywhere, oh eternal nowhere, oh eternal — for free!9

What does Zarathustra have to answer this lawsuit? Does the permanent migration of itself become a permanent standstill simply because every movement in it becomes meaningless, equal—valid? His answer is surprisingly defensive:

You're my shadow! He said at last, with sadness.

Your danger is no small, you free spirit and wanderer! You've had a bad day: make sure you don't have another worse evening ahead of you!

In the end, even a prison seems blissful to such wrongs like you. Have you ever seen captured criminals sleep? They sleep peacefully, they enjoy their new security.

Beware that you don't end up with a close faith, a harsh, strict delusion! In fact, you are now seducing and trying everything that is tight and firm.

You've lost the goal: Woe betide, how are you going to make up and get over this loss? So — you've lost your way too!

You poor sweetheart, you tired butterfly! Do you want a rest and home this evening? So go up to my cave!

That's where the road leads to my cave. And now I want to quickly run away from you again. It's already like a shadow on me.

I want to run alone so that it gets light around me again. I have to be funny on my feet for a long time to do that. In the evening, however, I do — dance! (Ibid.)

Can Zarathustra respond to the “shadow” at all?

IV. Walking as Dancing

From Nietzsche's point of view, Kierkegaard would probably be one of those apostate free spirits who set off courageously in order not to endure the heights of liberation in the end and allow themselves to be captured by a “harsh, strict delusion.” He describes aimlessness as just as much as the choice of any goal because you can no longer bear it.

Kierkegaard's answer would probably be: “It is not correctly understood that I chose the goal — faith — but faith chose me and brought me out of the desert into which you have fallen. Go within yourself and you will also hear the call within yourself.” The metaphor of “life.”10 suggests that Nietzsche imagines the way out of nihilism in a similar way: opening himself up to “something” that lies outside of one's own subjectivity and gives you a new orientation; for him, this simply has nothing to do with dedication to “God,” but is about opening up to the diversity of life itself, which inspires ever new goals. In order to stay in the picture, you probably have to imagine that it would be a matter of letting the environment dictate the route again and again. It's just a question of perspective: You haven't lost your way, on the contrary, you've always arrived.

But Nietzsche himself does not end up with a kind of faith himself, perhaps even with the western god, whom he describes, now strangely enough in a derogatory way, as an eternal wanderer: “In the meantime, just like his people themselves, he went abroad, he never sat still anywhere since then: until he finally became at home everywhere, the great cosmopolitan.”11. Isn't that Nietzsche's own dream, is being Isn't God actually the “god of all dark corners and places, of all unhealthy quarters in the whole world” (ibid.)?

The ambiguity of emphasis on migration and doubt is as much a part of the hiker's existence as his staff and footwear. We can infer both dimensions from Nietzsche's writings and feel invariably drawn to one, sometimes to the other — because it is the ambiguity of our own existence. We should avoid trying to separate one of the two — because what would we be without our shadows?

The dance, which Zarathustra also invites his shadow to do, describes an existence that exactly that ambivalence “[z] wipe saints and harlots, [z] wipe God and the world.”12 Able to take on yourself. Interestingly enough, Kierkegaard also uses this metaphor now and then to create such a successful existence in limbo, on “smooth [m] ice.”13 to describe. But it is, and here too both thinkers agree, a tightropeDance, one that also implies the risk of falling: “Man is a rope, tied between animal and superman, — a rope over an abyss”14. — In different ways, both thinkers lose balance on their own journey.

To sum up, metaphors of movement have always been used to describe basic modes of existence. In the sense of Hans Blumenberg's concept of “absolute metaphor,” they condense the lifestyle of an entire culture and from them it is possible to see what their approach to the world is.

sources

Kierkegaard, Soren: The term fear. In: The term anxiety/Prefaces. Collected works and diaries. 11th & 12th abbot. Translated by Emanuel Hirsch. Simmerath 2003, pp. 1—169.

Ders. : Fear and trembling. Collected works and diaries. 4th abbot. Transacted by Emanuel Hirsch. Simmerath 2004.

Item photo: Caspar David Friedrich: The Arctic Ocean (1823/24)

Source for all images used: Wikipedia

footnotes

1: Ecce homo, Why I'm so wise, 1.

2: Ecce homo, Human, all-too-human, 4.

3: Human, all-too-human I, Preface, 3.

4: See e.g. Morgenröthe, Aph 314.

5: Human, all-too-human II, Mixed opinions and sayings, Aph 21.

6: On the genealogy of morality, III, 26.

7: Subsequent fragments 1884, No. 28 [64].

8: So Zarathustra spoke, The Wanderer.

9: So Zarathustra spoke, The shadow.

10: See e.g. So Zarathustra spoke, The dance song and The other dance song.

11: The Antichrist, 17.

12: The happy science, An den Mistral.

13: The happy science, For dancers.

14: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 4. On the (rope) dance metaphor in Kierkegaard, see for example The term fear, p. 54 and Fear and trembling, P. 35.