Riveting Strangeness

Remarks on Kafka's Work

Riveting Strangeness

Remarks on Kafka's Work

Franz Kafka died 100 years ago. The following text is an attempt to update his work with a socio-psychological perspective inspired by Nietzsche. His thesis: Kafka narratingly shows what Nietzsche philosophizes about. Michael Meyer-Albert wants to promote the logic of a non-naive world enlightenment in the fictions of one of the most important authors of modern times: affirmation of life instead of suicide.

Editorial note: We have explained some difficult technical terms in the footnotes.

“[...], was it a comedy, that's how he wanted to play along. He was still free. ”

Kafka, The process

I. Kafkaesque

In Woody Allen's movie Play It Again, Sam From 1972, there is a scene in a museum in which the protagonist Allan somewhat clumsily addresses a woman who is absorbed in looking at a painting. He tries his luck by asking her what the picture means to her. Instead of looking at him, she describes in a sonorous monologue her fascination with the existential pessimism that the painting has for her. In his different kind of fascination, Allan does not address the flood of dark philosophems and simply asks whether the lady happens to have time for a date on Saturday. She replies — apparently her existential pessimism is more serious — that she cannot on Saturdays, she would commit suicide on that day. Allan is not discouraged by this and asks somewhat desperately whether a meeting could then be set up on Friday. — One of the following scenes shows the two naked in an apparently post-coital situation in bed. Shy and nervous, Allan asks how she found sexual intercourse. Her answer: “It was Kafkaesque. ”

In this passage, Allen's film profoundly shows how Franz Kafka's inheritance collapsed into a phrase. In a jargon of absurdity1 It functions as a kind of marker for the vocabulary of a negative worldview, which, thanks to its automatic fluency, skips over into inappropriate situations in a context-insensitive way. “Kafkaesque” connotes the fundamental absurdity of life. While in Kafka the absurdities of life usually express a gloomy surreal hopelessness, Allen's film points out that existential absurdities may well take a different direction. Sex instead of suicide. The following sections aim to promote this Nietzscheanization of Kafkaesque in a philosophical way. For a poetic approach with a similar thrust, reference is made to the work of Wilhelm Genazinos, which describes the “overall strangeness of life” in humorous detail.

II. Kafka's Wound

Kafka is one of the key witnesses of modern philosophy, which despairs of modernity. His work is regarded as a collection of evidence for the dark truth of the “managed world” (Adorno). The fact that art must serve as a guarantor of this truth can, however, be regarded as an indication that philosophy alone no longer dares to say what is. But as a volunteer maid of art, thinking only appears at first glance in a new modesty. Philosophy as a queen maker reserves the right to have the last word on what art actually does best. This role of hermeneutical decipherment is also predestined for the development of works of art in modern times under the convention of the unconventional, which descend into ever more cryptic originals. Philosophy becomes a priesthood of aesthetics. Through the detour of art, she regains the consecration of metaphysical truth. Modern art also benefits from this, whose manic enigmatics can now imagine that it is of transcendental origin. A tongue-in-cheek reference to the show of the show ranges from Plato ion up to Sigmar Polkes: “Higher beings ordered: paint the upper right corner black! ”

In addition to Heidegger, it was Adorno in particular who wanted to save philosophy about the interpretive sovereignty of significant works for the truth again. After an attempt to valorize itself as an understanding, not just positivistic, intellectual science, as a form of interpretation of art, becomes new. In addition to Beckett and Schönberg, for Adorno Kafka, from whose work he wants to derive legitimacy, it is the modern world In bulk to defame it as the demiurgic hell of the “existing”.

The tragedy of Adorno's philosophy is that her stupendous sensibility is manipulated by her dogma of world pain. Her negation of abstract worldviews does not protect her from once again propagating a deeply resigning worldview, which is transmitted indirectly through repeated patterns of interpretation that interpret what is as a great misfortune overall. Adorno thus instrumentalizes Kafka as a confirmation of his gnostic2 prejudices. He thus disguises himself with an enriching look at Kafka's work. And this despite the fact that he made it more accessible with sentences like this, which testify to his great aesthetic sensitivity: “Every sentence speaks: interpret me, and no one wants to tolerate it. ”3

With a socio-psychological approach, Kafka's wound could be understood in a more metaphysical way. It quickly becomes clear: Kafka had Daddy issues, eExemplically readable in The verdict in the form of Georg Bendemann or also in Letter to Father. The conflict is easy to understand: Kafka's father came from very simple backgrounds, the son of a butcher from a village of 100 people, who then sought his fortune in Prague and founded a gallantry shop there with the help of his wealthy wife. As a successful entrepreneur who wanted to and did it, he had no sympathy for a son who wanted to live for literature alone.

Kafka's father problems become philosophically demanding when interpreted in terms of cultural history. The figure of the father then figures as an educational authority that continues the act of birth in extended dimensions. The father as the complementary mother introduces society and cultural spaces. His authority thus appears not only as a diffuse form of imperious power, but as a superior pattern of competence. Seen in this light, Kafka's work is not indicative of the world of bureaucratic forms of rule, but is also a sign of the abysmal effects that occur when the connection between generations is no longer conveyed through traditions that can achieve sufficient plausibility for descendants. Kafka's diary is a hodgepodge of evidence of a placeless existence:

Without ancestors, without marriage, without descendants, with wild lust for ancestry, marriage and descendants. Everyone reaches out to me: ancestors, marriage and descendants, but too distant for me.4

I'm more insecure than I've ever been, I just feel the violence of life. And I'm pointlessly empty. I'm really a lost sheep at night and in the mountains, or like a sheep running after that sheep. Being so lost [...].5

I'm completely empty and pointless, the passing electric has more vivid meaning.6

When authorities, as plausible patterns that can be imitated and varied, are only experienced as alienating powers, the learning of a halfway extensive coming to the world fails: “My life is hesitation before birth. ”7

Kafka's work thus shows the first phase of this termination of a cultural tradition8 as a result of a generational process that was characterized by two world wars and resulted in the prevailing mood of universal helplessness.

In the second phase, the Joseph Ks are mobilized by more aggressive reddish brown heresies, which can name the alleged culprits for his plight and show him radical ways out. Dostoyevsky's scariest novel The demons (1872) narrated this basic tension, which was to become so dominant for the 20th century, in a prophetic deep psychology. It is exactly the preform of this tension that the monkey Rotpeter in Kafka's story A report for an academy describes in the following words: “No, I did not want freedom. Just one way out; right, left, wherever; [...] . ”9

III. Nietzsche's possible notes on Kafka

There are no explicit records of Nietzsche in Kafka. However, it is said from Max Brod, Kafka's childhood friend, that his first acquaintance with Kafka took place in an intensive discussion, during which Kafka criticized Brod's advocacy for Schopenhauer with a reference to Nietzsche.10

Nevertheless, Nietzsche allows us to deepen a socio-psychological view of Kafka's work by taking a step towards a metaphysical perspective. It does not describe Kafka's literature as supposed theology in the sense of modern Kabbalah11 read, but as an excavation site for philosophical archaeology that clarifies the trace effect of cultural concepts. With this view, two paradigms of suffering can be distinguished in Kafka's dark narrative universe. His two major works of novels may represent this. This is how thematized The castle Implies the platonic remoteness of being, which starts from a melancholy distance between the earthly world and the eternal good. Despite all traces and attempts at rapprochement, the best remains inaccessible. The sirens are silent. The novel The process In turn, you could read as an update of the Augustinian doctrine of hereditary sins — which moralizes Plato's distance from being — in the guise of modern bureaucracy. An inexplicable sense of guilt determines life like an anonymous force. All efforts in a bureaucratic process to obtain information about the character of this guilt, clarification and justice ultimately fail. The Kafka wound is therefore not an indication of the “managed world” (Adorno), but the trail of powerful metaphysical traditions that massively shape basic understandings and moods in the modern age.

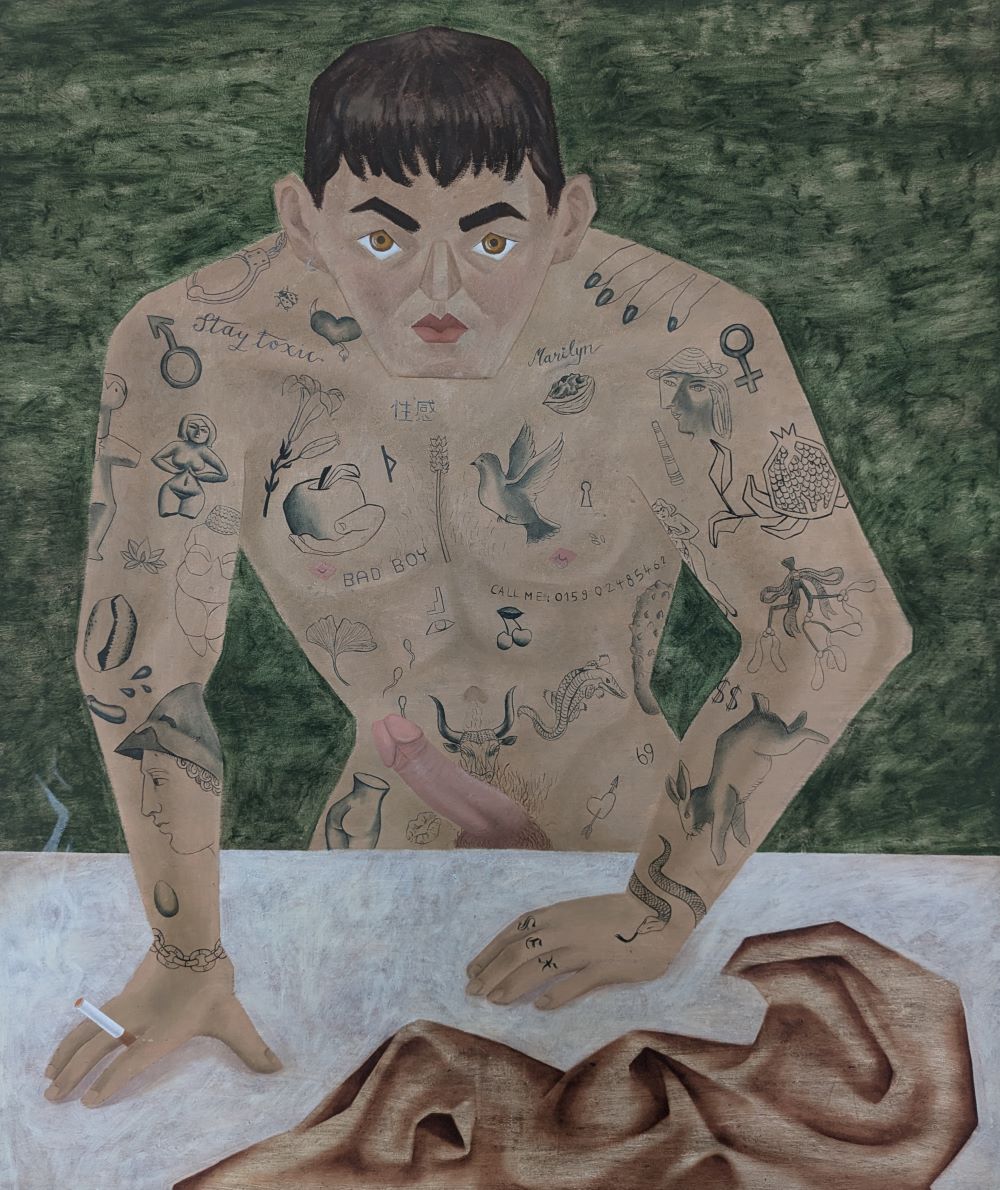

If you follow this reading, the unnecessarily masochistic of Platonic Augustine existentialism in Kafka — presumably conveyed primarily by Kierkegaard — presumably conveyed primarily by Kierkegaard — is revealed in a variety of details. For example, when the starving hunger artist is juxtaposed with the “joy of life” in the form of a panther — “that noble body equipped with everything necessary to just about tearing it apart”: “He lacks nothing. ”12

IV. Beautiful mystery

Kafka's works, however, are more than mere footnotes to Plato or Augustine. My suggestion is to read his literary work as an implicit existentialism that highlights the contingency of being in a modern way.

For a positive connotation of existential contingency, Nietzsche has found the liberating perspective of understanding life as an “experiment of the discerning.” However, this requires that you learn to say goodbye to the central ontological paradigms of Western culture. There is no being as a central center of origin that radiates to the margins and there is no justifying Advent13, who will one day be in a better world. Not a philosophy of history, not an entirely different one. The “non-identical” (Adorno) and the feeling of “abandonment” (Heidegger) are chimeras that arise from the fact that the contingent is unnecessarily resubstancialized into an emergency, against which inaccurate aggression is then released again. Kafka's poetic project could be combined with Nietzsche's philosophical project in the idea of an Apollonian transfiguration:

Could we ourselves an incarnation of dissonance think — and what else is a human being? — so this would dissonanceIn order to be able to live, you need a wonderful illusion that covers a veil of beauty over your own being.14

Kafka's Apollinism, however, is latent second-level Apollinism. His prose shows ways of making a minimal residual effort to the unlivable dissonance with the world through its portrayal as an unlivable dissonance. The explication of hermeneutical perspectivism is central to this. In Kafka's texts, the puzzle world is objectified through failed objectifications of the protagonists. Often, entire systems of understanding are continued, their autopoietic15 Dynamics contrast with the situation they are responding to. There is no confirmation. The whole thing is the strange thing that makes reflection fail: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” (Beckett) What is more bizarre than Gregor Samsa, who mutates into a “tremendous bug” but is primarily concerned about the inconvenience that his absence from employment causes? In this way, Kafka's texts look like legends that do not explain the inexplicable with the gesture of explanation. Indirectly, the uncanny is thus transformed into something strange. A world that is too incomprehensible becomes more understandable by understanding its understanding as remaining incomprehensible. Each sentence speaks from an ordinary point of view, but everything remains unusual.

This not only continues the eternal conversation with and about the overall puzzling nature of the world, but also makes it possible, because its questionability is now more prominent due to the inadequacy of understanding. In these attempts to implicitly transform the disharmonious into the enigmatic, Kafka's works are, from a cultural functionalist point of view, representations of provisional attempts to merge horizons. Their irritations harmonize because they illustrate an understanding that becomes understandable when not understood. Demonstrated insanity creates an irony to make sense, but this must be the case. Kafka's prose is an exculpatory propaedeutic for the dissonance that we are. It transfigured the glorification. Contingency is felt in the ambivalence of an underlying mood of “beautiful stranger” (Eichendorff).

V. The tired wound

Kafka's enigmatic objectifications of the enigmatic also have cultural-philosophical significance for Nietzsche readers. In an in-depth way, they explore the idea of being doomed to transfiguration. In addition, they show traces of what it means to no longer be obscured by God's shadows. It is not Kafka's wound, but the mysterious nature of Kafka that stimulates awareness of the attractive mystery of life called for by Nietzsche in the medium of philosophy, a little too cocky and slogans. Explication of the enigmatic stimulates mental vitality. Something interesting can now be found in everything. The futility of understanding is converted into a license to poetize. Through Kafka's art, the enigmatic character of the world becomes clearer as an opportunity for plural participation in the expression of hermeneutical diversity. Freedom can be when understanding becomes a game through failure. Especially without a king's message, the individualized couriers of the modern age are no longer miserably senseless at the mercy of their talk of reports. It is not an oath of service that obliges them to live, but an increased availability for the outrageous events tempts them to tell an encouraging story of the eternal novel World and a new engagement on their stages.

This transformation of the uncanny life process into an unforeseeably interesting mystery has the effect of cultural therapy peripety16. Kafka narratively shows what Nietzsche philosophizes about. In the midst of the fictionalization of permanent self-charges, which are based on an incomprehensible sense of guilt (cf. The process) and paranoid uncertainty (cf. The building) and the latent idea of a depressing, irrevocable distance to be fulfilled (cf. The castle), there are unKafkaesque passages here and there in Kafka that suggest emancipatory changes in the Platonic Augustine powers. The self-feeling of being a nobody without authority from the very top is released from the urge for redemption through grace and recognition, not to mention from the heroic desire to win and revolutions. Kafkaesque could become the contingency of existence for an honest “will to serve life” (Thomas Mann), to which the absurd was conveyed as a nice arbitrariness and possible beginnings of victories over banality. Nothing must, everything can. Angelus Silesius's well-known slogan would have to be reversed: Man, become irrelevant. An idea of a cocky contingency that honors chance as a source of opportunity is conveyed, for example The trip to the mountains:

“I don't know,” I shouted without a sound, “I don't know. If no one comes, then no one comes. I've done no harm to anyone, no one has done anything bad to me, but no one wants to help me. No one at all. But that's not the way it is. Except that no one helps me — otherwise no one would be pretty. I would really like — why not — to go on a trip with a company of no one. Into the mountains, of course, where else? ”17

Also for the paranoid mole in Kafkas The building Are there phases in which he lucidly distances himself from his incessant “defense preparations”: “Until, gradually, with complete awakening, disillusionment comes, I barely understand the haste, deeply inhale the peace of my home that I have disturbed myself, [...] . ”18

Kafka evaluates Kafka most clearly in the parable prometheus The values of the West. Prometheus, an ancient Christ on the cross, experiences a resurrection through the healing power of time, causing “the whole tragic Prometheia of all discerning people”19 Like a sandcastle on the seashore, disappears in the waves. No wound distracts from the puzzle of mere existence anymore:

The legend tries to clarify the inexplicable; [...] Four legends report about Prometheus. After the first, because he had betrayed the gods to humans, he was forged into the Caucasus and the gods sent eagles that ate from his ever-growing liver. [...] After the fourth, people became tired of what had become baseless. The gods got tired, the eagles. The wound closed tired. What remained was the inexplicable rocky mountains.20

sources

Adorno, Theodore W.: Notes about Kafka. In: Collected works 10/1: Cultural Criticism and Society. prisms. Without a mission statement, Frankfurt am Main 1977.

Kafka, Franz: narratives. Stuttgart 1994.

Ders. : Diaries. 1910-1923. Stuttgart 1967.

Oschmann, Dirk: Skeptical anthropology. Kafka and Nietzsche. In: Thorsten Valk (ed.): Friedrich Nietzsche and the literature of classical modernism. Berlin 2009, pp. 129—146.

footnotes

1: Analogous to the “jargon of authenticity” that Adorno emphasized in Heidegger and his epigones.

2: Editor's note: “Gnosis” means the conviction that the world in which we live is not the creation of God, but of a subordinate, vicious “demiurge.”

3: Adorno, Kafka notes, P. 255.

4: Kafka, diaries, p. 402 (January 21, 1922).

5: Ibid., p. 236 (November 19, 1913).

6: Ibid. (November 20, 1913).

7: Ibid. p. 404 (January 24, 1922).

8: Editor's note: The implantation of the early form of the embryo resulting from the fertilized egg into the lining of the uterus.

9: Kafka, narratives, P. 202.

10: Cf. Oshman, Skeptical anthropology. Kafka and Nietzsche, P. 129.

11: Editor's note: Mystical tradition of Judaism.

12: Kafka, narratives, P. 235.

13: Editor's note: In addition to the first advent of Christ, the term “Advent” describes his return.

14: The birth of tragedy, Abs. 25.

15: Editor's note: “Autopoiesis” describes the process of self-creation and maintenance of a system.

16: Editor's note: In literary theory, the turning point of an action.

17: Kafka, narratives, P. 22.

18: Ibid., p. 468.

19: The happy science, Aph 300.

20: Kafka, narratives, P. 373.