“Peace Surrounds Me”

An Unusual Christmas Message

“Peace Surrounds Me”

An Unusual Christmas Message

In our last article before the break at the turn of the year, Paul Stephan explores a Close reading A remarkable aphorism of Nietzsche, in which he expresses himself with the famous Christmas blessing “Glory be to God in height and peace on earth and to people! “discusses. As when unwrapping a gift that has been covered several times, he tries to reveal the different layers of meaning in this text in order to make Nietzsche's exact positioning clearly stand out. The reader may decide for himself whether you end up holding a glowing truth in your hand or the box remains empty. In any case, we wish all our readers with Nietzsche: “Peace on earth and good pleasure for each other! ”

I. The “golden loot”

The golden loot. — Many chains have been put on man so that he will forget to act like an animal: and indeed, he has become milder, more spiritual, more joyful, more prudent than all animals are. But now he still suffers from wearing his chains for so long that he lacked pure air and free movement for so long: — but these chains are, I repeat again and again, those serious and meaningful errors of moral, religious, metaphysical ideas. Only when the chain disease has been overcome, the first major goal has been fully achieved: the separation of humans from animals. — We are now in the midst of our work to remove the chains and need the utmost care. Nur the refined man May freedom of mind to be given; to him alone approaches making life easier and anoints out his wounds; he may first say that he is responsible for Happiness Live for the sake of no further goal; and on everyone else's lips his motto would be dangerous: Peace around me and pleasure in everything close to me. — In this motto for individuals, he remembers an old great and moving word, which allen was considered, and that has stood above the entire human race, as a motto and landmark, on which everyone who adorns their banner with it at an early stage — on which Christianity was the basis. Still, it seems Is it not timethat it all People may be like those shepherds who saw the sky illuminated above them and heard that word: “Peace on earth and good pleasure for people in one another.” The time of individuals.1

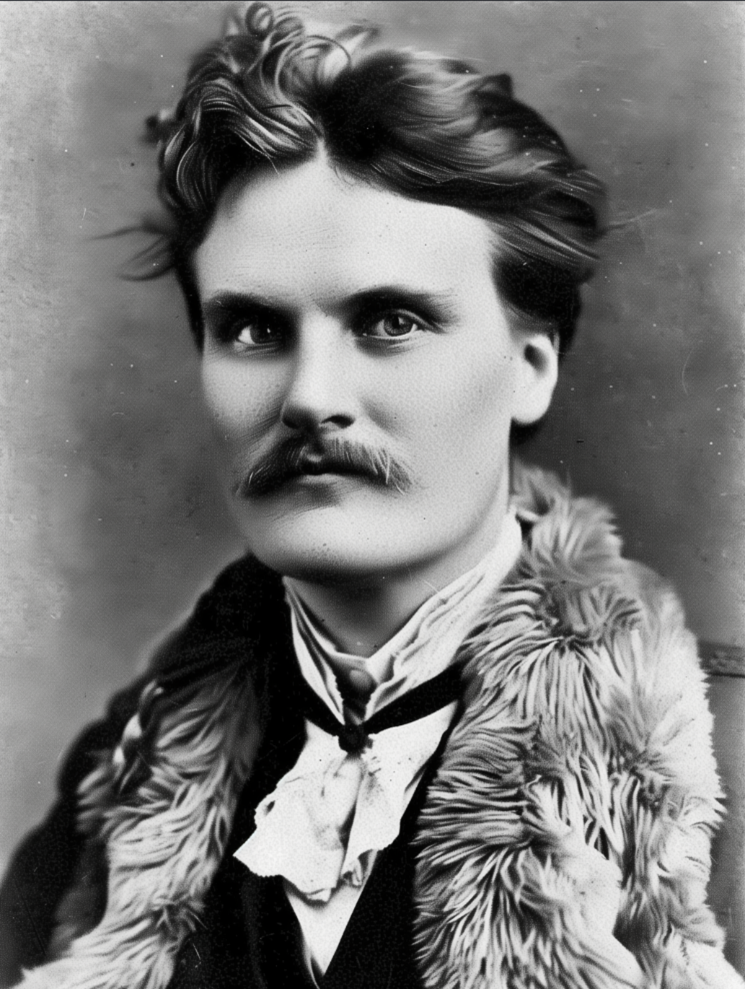

With this aphorism, Nietzsche ends the second part of the second volume of Human, all-too-human, which is overwritten with The Wanderer and His Shadow. Looking back, Nietzsche describes this book as the document of a major personal crisis:

Back then — it was 1879 — I resigned my Basel professorship, lived like a shadow in St. Moritz over the summer and the next winter, the sunniest of my life, than Shadows in Naumburg. This was my minimum: “The Wanderer and His Shadow” was created in the meantime. Undoubtedly, I knew shadows back then...2

It is easy to see that a transformation is taking place in the second volume of his first large collection of aphorisms. The first volume of the “Book for Free Spirits”, which was published in 1878, is still entirely in the light of an enlightened and individualistic intellectual libertinage. The first edition is dedicated to the enlightener Voltaire, who had died a hundred years earlier. In the two supplements to this book — Mixed opinions and sayings And just The Wanderer and His Shadow —, which initially appeared as separate books in 1879 and 1880 and were only published as one book in 1886 together with the first volume, it does in fact strike a different, 'darker' and more thoughtful tone. Self-reflectivity is increasing, the style is becoming more paradoxical. Nietzsche increasingly becomes the doubting “hammer” of his later writings.

However, this final aphorism is now remarkably 'light'. In the first section of the aphorism, up to the second indent, he clearly represents the program of enlightenment humanism. Humans should overcome the animal within themselves and become “milder, more spiritual, more joyful, more prudent.” Zarathustra's ideas of “self-overcoming” and “superman” are suggested here, but without the “dark” twist that Nietzsche would later give them.

This is followed, up to the next indent, by the thesis, which could actually be described as Nietzsche's “basic view” and to which he should remain loyal from early work to late work: that in order to realize his very own potential, man must free himself from the “chains” of traditional metaphysics and morality, which have so far oppressed him and allowed him to remain in a state of animality.

This phrase is surprising, as those “errors” justify themselves precisely by creating a break between animals and humans. The biblical story of the fall of sin already tells of how this break in the world came about. Nietzsche diametrically reverses this familiar perspective here — how is he able to justify that?

Until the next indent, however, there is no answer to this obvious question, but a new twist in Nietzsche's argument by citing another of his core theses: that not everyone should be allowed to liberate themselves spiritually equally in their own sense. This life without moral ties should be reserved for “refined people.” His motto is — this is also a typical Nietzsche stylistic device — a variation of the Christmas Annunciation, as it is still read every year in churches on Christmas Eve.

At the end of the aphorism, this is quoted, although again slightly varied. In the classic wording of the Luther Bible, with which Nietzsche was of course very familiar — here in the 1912 version, which largely corresponds to him — the slogan is: “Glory be to God in the highest and peace on earth and to people! “(Luke 2, 14) It is a collective prophecy of the “multitude of heavenly hosts” (Luke 2, 13) to the shepherds as representatives of the common people.

However — and Nietzsche may have known this — the original Luther Bible follows a reading of the original Greek text that is now considered obsolete. The latest version of this translation from 2017 is therefore somewhat different: “Glory be to God in the highest and peace on earth among people of his good will. “This is therefore no longer a promise of mercy and peace to really all people, but only a promise of peace to those who share God's “goodwill.”

If you leaf forward one chapter in the Gospel of Luke, it becomes clear how this restriction could be meant, because it says in the famous hymn of praise to Mary (translated from 2017): God's “mercy lasts for and for those who fear him. He exercises violence with his arm and disperses who are arrogant in their heart's mind. He knocks the powerful off the throne and elevates the lowly. He fills the hungry with goods and lets the rich go out empty-handed.” (Luke 1, 50-53) The New Testament is therefore not necessarily about a shallow 'God loves all people, 'but a revolutionaries Message: God only “loves” people who believe in him and who are not “arrogant.” In particular, the rich and powerful are excluded here, as in countless other places in the book. — From this perspective, Nietzsche's first reversal of blessing sounds very “arrogant”: The free spirit only wants to yourself Live in peace and harmony with things that him surround.

This also raises questions again. Exactly why is it not yet time for this solution? What would have to happen so that it could be set up as an ideal? And how can it be explained that Nietzsche, on the one hand, proclaims a break with all previous ideals, but at the same time puts them into perspective, insofar as he even approves of the utopian goal of Christianity? — The fact that Nietzsche adopts this goal is underlined by the fact that he uses this formula — “Peace on earth and people to please one another! “— completed a postcard which he sent to his student and confidante Adolf Baumgartner on 23.12.1878.3

II. Peace or Good to each other!

Two estate fragments from the 1880s illustrate that Nietzsche will answer the sensitive questions that this aphorism raises but leaves open by distancing himself from the goal of Christianity more than here. “Peace and good pleasure for people” now appears to him as the slogan of “decadence,” which expresses itself in the inability to resist others, in tolerance, compassion and tolerance. This morality of weakness should now be replaced by an ethic of strength and toughness, which in no way has “peace” and “good pleasure in one another” in mind, except in the sense of the first slogan.4

He now aggressively represents amorality:

“Illness makes people better”: this famous statement, which has been encountered throughout the centuries, in the mouths of the wise as well as in the mouths and mouths of the people, makes one think. In view of its validity, one would like to allow oneself to ask: Is there perhaps a causal link between morality and illness at all? The “improvement of man”, on a large scale, for example the undeniable alleviation of the humanization of the European within the last millennium — is it perhaps the result of a long secretly eerie suffering and misjudgment, deprivation, atrophy? Has “the disease” made the European “better”? Or to put it another way: is our morality — our modern tender morality in Europe, with which one might compare the morality of the Chinese — the expression of a physiological Decline?... One does not want to be able to deny that every passage in history where “man” has shown himself in particular splendor and power of the type immediately assumes a sudden, dangerous, eruptive character in which humanity goes bad; and perhaps it has in those cases where it Wants to seem different<er>, simply lacked the courage or subtlety to delve into psychology and extract the general sentence there as well: “The healthier, the stronger, the richer, more fertile, entrepreneurial a person feels, the more “immoral” becomes.” An embarrassing thought! You definitely shouldn't hang on to it! But assuming that you run forward with him for a short, brief moment, how astonished do you look into the future! What would then pay off on earth for Theurer than just what we are demanding with all our might — the humanization, the “improvement,” the growing “civilization” of humans? Nothing would be more expensive than virtue: because in the end, you would have Earth as a hospital: and “Everyone's Nurse” would be the ultimate wisdom. Of course, you would then also have that much-sought after “peace on earth”! But even so little “pleasure in one another”! So little beauty, exuberance, risk! So few “works” for which it was still worthwhile to live on earth! Ah! And absolutely no more “thats”! All big Works and deeds that stood still and were not washed away by the waves of time — were they not all great immoralities in the deepest sense? ... 5

The rule now is: either peace or “Pleasing one another.” When people behave peacefully when they are weakened, they cannot experience authentic mutual pleasure.

This looks like an attempt at the aphorism The Wanderer and His Shadow to back up argumentatively, at least retrospectively. Christianity failed to achieve its ideal because it made two adversarial demands. Of course, this not only makes it “not yet” realizable, it is never realizable and not even suitable as an ideal. Only the individual requirement of the individual to come into harmony with himself and to value his immediate environment can be regarded as such. But Nietzsche does not want this to be addressed to everyone, but only to strong natures, who are also worth affirming themselves. The weak should calmly deny themselves and live in discord with themselves and their environment — their nature predestines them to do so anyway.

The original revolutionary meaning of the Christmas Blessing only reinforces Nietzsche's reservations. This is obviously about what Nietzsche said in On the genealogy of morality is described as “slave morality”: The strong should be held down and tamed in order to make general peace possible. But Christianity fails to recognize that this only creates a boring, grey, “nihilistic” world in which there is nothing more to affirm about humans. Instead of transcending the animal in humans, people are transformed into pets.

III. Un-Christmassy — all-too-Christmassy?

There is certainly something to Nietzsche's thoughts. Everyone knows social contexts in which everyone is terribly nice to each other, but in fact no real interpersonal resonances can arise, precisely because these include conflict and honesty. They often have a dull, stuffy atmosphere, like at a family party. Many probably experience Christmas in exactly the same way, as the epitome of Christian lies and hypocrisy. Let these people love themselves first and come to terms with themselves before they give others their “compassion”!

But the Nietzsche from The Wanderer and His Shadow It's not as easy as the later one. This is not about naturally strong individuals, but apparently those who have been “ennobled” in an educational process and have therefore truly become master of their secret desires and urges; who are “strong” in the sense that no remnant of unsublimated animality has remained in them. For whom, in Freud's sense, where “it” was, has become “I.” Only they could be truly peaceful with others without having to lie to themselves. So they are peaceful with others not because they should, but because they really want to. However, if this ideal is imposed on everyone, even those who are not yet ready for it, it only leads to hypocrisy and inner conflict. You're nice to everyone, but in reality you're full of aggression — for which you then hate yourself.

In this aphorism, however, Nietzsche still considers it possible and even desirable for all people to “refine” themselves in this sense and be at peace with themselves and their environment in such a way that real peace could reign in the world. Only then could people truly value each other. And peacefulness and appreciation would no longer be something that you would have to morally decree, but what would result from this enlightened, authentic consciousness agreed upon with yourself.

In the end, that would be Nietzsche's “happy message” at Christmas time: Respect, compassion, charity and all other ideals of Christianity cannot be dictated or demanded morally; they must arise out of genuine self-affirmation and self-control. True morality must come from within. Christianity deceives people in Nietzsche's account by promising such morality without any effort of its own. All you have to do is get rid of the 'bad people, 'and then everything is good. But peace can only spread around themselves and truly appreciate others, anyone who has found inner peace through their own efforts and who values themselves. — But is that so anti-Christian at all and doesn't Christianity rather remind Christianity of its own core? In any case, it is a very different message than the one you usually hear at Christmas.

footnotes

1: Human, all-too-human II, The Wanderer and His Shadow 350.

2: Ecce homo, Human, all-too-human 1.

4: Cf. Subsequent fragments 1888 23 [4].