February 11, 2026 2:02 PM

Henry Holland

Tobias Kurpat geht dieses Thema gekönnt essayistisch um: Die Figur der Barbaren wird umgekreist, statt mit systematischer Schwere festgenagelt. Dabei wird aber die linke Nietzsche-Rezeption zu einfältig dargestellt, die Linken schon wieder zur wahren Helden der Geschichte stilisiert: Und eine wirklich Auseinandersetzung mit den Rechten—bis hin zu einem Zitieren dieser Rechten, kann man sich das vorstellen?—, aus dem Weg gegangen.

Anders als von Kurpat dargestellt, wenige aber wirkungsvolle Vertreter eine linke Nietzsche-Rezeption haben Nietzsche sehr wohl "beim Wort" genommen: Und auch zurecht, bezüglich mehreren Schlüsselthemen. Hier ist vor allem der Historiker Domenico Losurdo zu nennen. Mit Statements von vielen Zeitzeugen, welche die erste Generation der Nietzsche-Rezeption mitgestaltet haben (u.a. viele Linken, z.B. Franz Mehring—im Spartakus/Anti-Kriegs-Flüger im 1. Weltkrieg), zeigt Losurdo überzeugend auf, dass 1. viele Nietzsches Zeitgenossen Nietzsche "beim Wort" nahmen; 2. dass in einigen Schlüsselthemen, N. wollte beim Wort genommen werden: Oder mindestens v. den Kreisen, die ihm Nahe stand. Hier z.B. ist George Brandes (in der englischen Übersetzung zitiert) reagirend auf Nietzsches tatkräftige Unterstützung der real existierende Sklaverei u. Eugenikpolitik: "For Nietzsche, the size of progress must be measured by the sacrifices it

requires. Hygiene that keeps alive millions of the weak and useless, of

people that would be better dead, does not for him constitute real pro

gress." (Zitiert nach Losurdo, engl. Spracheausgabe, 2022).

Wo Kurpat und ich eventuell übereinstimmen würden (hoffe ich zumindest), ist die Realisierung, unabhängig der Verwerflichkeit einiger Nietzsches politischen Überzeugungen, dass es fatal wäre, ab jetzt seine Erbe nur den Neuen Rechten zu überlassen. Aber um in dieser Sache etwas zu erreichen, muss man wegkommen von der intellektuellen (und manchmal auch ethischen) Überlegenheitsgeste, welche die Linke so sehr auf die eigene Fahne schreiben. Es mag sein, dass die Linke in dieser Debatte durchgehend u. auch schlussendlich "im Rechten" waren und es immer noch sind: Dass wird aber die bei den neuen Rechten, oder aber auch die noch Unentschlossenen, herzlich wenig beeindrucken. In dieser psychologischen Konstellation, ist es mehr als fragwürdig was Kurpat mit dem Vorwürfen der "Pseudowissenschaftlichkeit" und des "Neoreaktionären" Seins gegen die Neuen Rechten erreichen will. z.T. Pseudowissenschaftlichkeit: Was hält dann Kurpat von den Unmengen von "Wissenschaft (?) (?)", die linkspolitischen AutorInnen derzeit in Peer-Reviewed-Journals zu wichtigen Themen wie "autoethnography", oder wie Lehrkräfte mit unterschiedl. Gender-Vorstellungen sich unterschiedlich verkleiden, veröffentlichen? Beispielsweise kann eine solche besagte Autor*in, wenn nur "gut genug", beim Peer-Review-Journal Social Sciences für nur 1800 Schweizer Frank (richtig: Achtzehnhundert)) "Article Processing Charge" veröffentlichen. Konkret über Themen wie "autoethnographic journals", denn dieser gehören zweifelsohne den "hard sciences" an, oder? (Aufgerufen 11.2.2026, https://www.mdpi.com/journal/socsci/special_issues/4DVOO1LC46

Parodie oder ein Stigmatisieren durch Ein-Wort-Beschimpfungen ("pseudowissenschaftlich") bringt Lesende auch nicht weiter, wenn es darum geht, die Nietzsche Lese-Art der Neuen Rechten tiefer zu verstehen: Und dadurch zu bekämpfen. Kurpat selbst hat das wichtige Thema der Genetik, und den Neuen Rechten Umgang damit, thematisiert: Ein Feld, wo die Eugenik immer wieder mitschwimmt. Aber statt realen Akteuren der neuen Rechten hierzu zu zitieren, z.B. Costin Vlad Alamariu, wessen 2023-Buch Selective Breeding and the Birth of Philosophy mitten in das Genetik-Eugenik-Feld einmarschiert, geht Kurpat auch hier eine echte Auseinandersetzung aus dem Weg. Persönlich halte ich Selective Breeding (2023) für komplett verwerflich, dennoch ehrlich (letzteres kann man nicht immer den Linken beim Umgang mit der Wissenschaft bezeichnen). Es gibt z.B. eine in Europa sozialakzeptierte Form der Eugenik (des "Selective Breeding"): Und vielleicht ist das richtig: Vielleicht soll es sie geben: Seit der massiven Ausbreitung der pränatale Diagnostik gibt es ein massives Zurückgehen von Menschen, die mit Downs Syndrome u. anderen (relative häufigen) Behinderungen geboren werden. In dieser Sache haben de Graaft et al. (2021) nachweisen können, dass die Anzahl der Menschen, die mit Trisomie 21/Downs Syndrom geboren sind, zw. 2011-2015 bei 54% (!) in Europa zurück gegangen ist: Verglichen mit der Geburtsrate, wenn es die selektive Abtreibungen nicht gegeben hätten. (de Graaf, G., Buckley, F., & Skotko, B. G. (2021). Estimation of the number of people with Down syndrome in Europe. European Journal of Human Genetics, 29(3), 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-00748-y, hier S. 403-404)

Frage, zuletzt: Wird gegen Unsafe House geschossen, weil House geg. HGB Leipig schießt? Seinen You-Tube-Kanal bezeugt das

der-ubermensch-im-hamsterrad

February 10, 2026 11:57 AM

February 3, 2026 11:57 AM

January 25, 2026 11:31 PM

January 22, 2026 10:58 AM

Henry Holland

Hats off to you, Dr. Dann, for your ability to still be moved! Back here amongst German-speaking intelligentsia, on the fringes of the Nietzsche Studies establishment, the gift of reacting emotionally to religious experience & thought is eyed with more than suspicion. Which again begs the question: for a diehard secularist, what moved Nietzsche to spend so much of his brilliant prose on this polemical (indeed often abusive) dialogue with religious people & movements, e.g., Islam & Christianity? And I love hearing the trouble-stirring Antichrist (aka F. Nietzsche), Rudolf Steiner, & Henry Thoreau mentioned in the same breath: despite the evidence of Nietzsche reading the American transcendalists (I think more Emerson than Thoreau) this vein has hardly been mined. Finally, a riff-off Pierre Klossowski's Muslim-inflected reincarnation fiction that is centered in Part II of my essay here on POParts: if Klossowski (his 1965 novel) has N. reentering existence as an anteater, which messages, spinning Klossowski's fiction further, would Nietzsche now have for his audiences if he were to reincarnate as a tour guide in the 2020s, in Genoa or Leipzig, two of his cities of choice?

friede-mit-dem-islam

January 21, 2026 8:06 PM

Kevin Dann

Thanks Henry Holland for your humane crying out into the streets: “Come, friends, let us meet the Other without collapsing into Fear!” while walking blithely and bravely right into the messy middle where beauty and hospitality and Fear and Charity live harmoniously in the same few blocks.

You do a graceful pas de deux round the dread anti–Semitism; you do what Nietzsche would demand, what Steiner would demand, what Thoreau would demand, what Kafka would demand—you try to SEE. Having been a tour guide for a decade in the belly of that Beast Gotham, I know the drill. Only a few courageous ones can pull it off as deftly as you do here.

The neighbor, the pakora, the charity shop, the beard, the sectarian awkwardness, the red sandstone, the heat—all the indispensable elements where the future will be decided. Bravo!

friede-mit-dem-islam

January 21, 2026 12:39 PM

Olimpia

Der „Barbarin“-Gedanke zieht sich als roter Faden durch Politik, Gesellschaft, Mode und Philosophie: Er beschreibt Frauen, die sich dem System nicht durch offenen Kampf, sondern durch bewusste Verweigerung entziehen. Ihr stärkstes Werkzeug ist das stille, kompromisslose „Nein“ – ein Nein zur Selbstaufopferung, zur Dauerverfügbarkeit, zum männlichen Blick und zu den alten Regeln der Macht.

Manche Frauen treten zurück, nicht, weil sie scheitern, sondern weil sie den Preis für grenzenlose Hingabe nicht mehr akzeptieren. Auch der leise Rückzug vieler Frauen aus der Kommunalpolitik ist Teil desselben Musters – ein Nein zu Hass, Sexismus und dauerhafter Angreifbarkeit. Gleichzeitig formieren sich Frauen fraktionsübergreifend neu und verweigern traditionelle Rivalität: Sie entziehen sich damit der alten politischen Logik.

Manche, statt als dekorative Figur neben dem Machtzentrum zu funktionieren, nutzen die Kleidung und Gesten nicht zur Bestätigung des Systems, sondern zur Abgrenzung. Wenn sie den Blick senken, schweigen oder Grenzen setzen, wird dies als Provokation gelesen – nicht weil sie etwas Falsches tuen, sondern weil sie sich weigern, die gesellschaftliche Pflicht zur ständigen Lesbarkeit zu erfüllen.

Die Metapher des tief ins Gesicht gezogenen Hutes bündelt dieses Prinzip. Er ist kein Versteck, sondern ein Schutzraum: ein Entzug des Blicks und damit der Verfügungsmacht anderer. Wer ihre Augen nicht sieht, kann sie nicht einordnen. Die Frau wird unlesbar – und damit unkontrollierbar. Mode wird zur Rüstung einer Subjektwerdung, die das System provoziert, weil sie die erwartete Gefälligkeit verweigert.

Ihr Verhalten ist ein praktisches „stilles Nein“: Sie lässt sich nicht in das erwartete Skript der gefälligen, stets verfügbaren politischen Partnerin pressen. Gerade diese Verweigerung macht sie zur Barbarin unserer Zeit – zu einer Frau, die ihre eigene narrative Macht behauptet, indem sie nicht liefert, was die Öffentlichkeit von ihr verlangt.

Philosophisch ist dies ein Akt der radikalen Autonomie. Die Barbarin bricht den „Blick des Anderen“ (Sartre), beansprucht Glissants Recht auf Opazität und verkörpert eine negative Freiheit im Sinne Berlins: Freiheit von Erwartungen, von Lesbarkeit, von Verfügbarkeit. Sie hört auf, ein Bild für andere zu sein, und beginnt, eine Existenz für sich selbst zu führen.

Das „stille Nein“ der modernen Barbarin ist damit keine Flucht, sondern ein Gegenentwurf. Im Schatten der Hutkrempe sammelt sie Kraft, definiert sich neu und bildet eine Macht, die alten Strukturen gefährlich wird: die Macht jener Frau, die nichts mehr beweisen muss – und die selbst entscheidet, wann und wie sie sichtbar wird.

barbarinnen---wenn-frauen-zur-gefahr-werden

January 21, 2026 12:01 PM

January 21, 2026 12:41 AM

January 19, 2026 11:24 AM

January 18, 2026 10:00 PM

January 17, 2026 11:05 PM

January 16, 2026 11:02 PM

January 16, 2026 8:40 AM

Mario Beilhack

Auf den Punkt und jetzt „auf die Schiffe“ ihr Philosophen! Verlassen wir die öden Gestade der Ressentiments!

vom-leugner-uber-die-verschworungstheorie-zum-ghosting

January 16, 2026 2:19 AM

angelika schober

ein sehr interessanter und guter artikel

vom-leugner-uber-die-verschworungstheorie-zum-ghosting

January 16, 2026 12:26 AM

January 13, 2026 11:43 PM

December 31, 2025 9:37 AM

December 31, 2025 6:14 AM

December 30, 2025 10:13 PM

December 29, 2025 9:43 PM

Paul Stephan

Ein kleines Update: Meine Tochter Charlotte Emma Luise wurde am 26. 12. geboren.

vater-sein-mit-nietzsche

December 27, 2025 6:24 PM

December 26, 2025 6:13 PM

Waldgänger

Ein Einwand gegen den vorherigen Kommentar (mma, 3.12.2025): Wenn Philosophie nur als erbauliche Erholung von der Abnutzung durch vermeintlich fortschrittliche technokratische und kapitalistische Betriebsabläufe dient, anstatt sich mit diesen kritisch auseinanderzusetzen, verkommt sie trotz ihres tendenziell nonkonformistischen Charakters zu einer affirmativen Parteinahme für das Bestehende. In diesem Sinn, nämlich zur Aufwertung eines an sich wenig rühmlichen "Mitmachens" - man will sich eben trotz allem den Anschein geben, irgendwie rebellisch zu sein -, haben heute so manche Philosophie nötig. Sich dies einzugestehen, ist vielleicht der erste Schritt, den philosophischen Anspruch einzulösen, der ansonsten mitunter in schreiendem Gegensatz zum tatsächlich praktizierten Verhalten steht. Übrigens gibt es an Nietzsche so manches zu kritisieren, nicht aber mangelnde Selbstkritik: "Wohlan, ich hatte Wagner nötig", gesteht er sich ein und erkennt sich somit im Rückblick als einen der "Täglich-Abgenützten", denen eben Wagners Inszenierungen "eine Art Ferien für Geist, Witz und Gemüth" zu bieten hatten. Es wäre schade, wenn sich Philosophie heute auf eine vergleichbare Funktion reduzieren würde. Dass sie inzwischen ein Nischendasein führt und man sich Zeit und Ressourcen freigeschaufelt haben muss, um sich tiefgehend mit philosophischen Fragen befassen zu können, ist unbestritten. Es hilft der Philosophie, inmitten funktionalistischer Abläufe und zunehmender Trivialität des Alltags gewissermaßen zu überwintern. Wenn sie sich allerdings nicht mehr aus ihrem Versteck hervorwagt, auf gesellschaftliche Entwicklungen Einfluss nimmt und mitunter zum Stein des Anstoßes wird, hat sie ihren eigenen Anspruch verfehlt.

der-sinn-ist-gefallen-doch-ich-traume-noch

December 26, 2025 4:55 PM

December 25, 2025 1:12 PM

December 25, 2025 11:50 AM

December 24, 2025 1:11 AM

December 22, 2025 9:17 PM

Paul Stephan

Maybe Rilke's poetic vision of a "belief without chapels which silently does it wonders" could serve as an inspiration for people of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim background alike to overcome the current horrible conflicts and work jointly on a world without fanaticism: https://youtu.be/ETmwrW7L7s8?si=GS8NKHH7WCqjnMkg

(And of course one should reread Lessing's "Nathan", always!)

friede-mit-dem-islam

December 22, 2025 9:07 PM

Paul Stephan

Thank you for your response to my comment.

Well, it does not address my main points but changes the topic to the war in Gaza which I only mentioned in a side note. And it does not even give one counterargument to my point that Islam chauvinism might by *one* reason (of many) why the conflict in Palestine is so persistent.

I could now write a lot about my analysis on Gaza but this was neither the topic of my comment nor of Henry's article so I prefer not so discuss it here.

I can just repeat myself here: Jewish chauvinism is of course a problem as well and also Christian chauvinism.

friede-mit-dem-islam

December 22, 2025 6:23 PM

Ferdinand Hardekopf

Holland's brave essay, which refuses to fall into the Islamophobic trap that the Right are working so hard to ensare us in, is hardly worthy of the clichéd predjudices that Paul Stephan and mma seem desperate to reduce it too. Dressed up as liberalism, but merely doing the donkey work of the Reaction, these two commentators are obssessed with turning the conversation back to Hamas, and Heinsohn's outdated and social-darwinistic concept of the "youth bulge": although Holland doesn't even mention these two themes. Because the article is not about them. The collective Stephan invokes in his comment, "us secular non-Muslim intellectuals," does not exist with regard to Muslims in Glasgow & other places in the Global North today: the actual subject of the essay. His splinter group, German-language intellectuals who remain ethically confused & paralysed by the legacy of the Holocaust, won't fail to take the chance to mention Hamas. But fail consistently to talk publicly on the real issue impacting Muslims worldwide: the ongoing and now rebranded genocide in Gaza and the West Bank. Fascinatingly, Haaretz, Israel's oldest Hebrew & English language newspaper, has no problem speaking directly to this reality: their June 26, 2025 report: "100,000 Dead: What We Know About Gaza's True Death Toll": https://www.haaretz.com/gaza/2025-06-26/ty-article-magazine/.highlight/100-000-dead-what-we-know-about-gazas-true-death-toll/00000197-ad6b-d6b3-abf7-edfbb1e20000?fromLogin=success Hamas, by comparison, with around 16,000 still active fighters, account for a whole 0.000008 % of the world's Muslim population. And Hamas' undeniable anti-Semitism is meant to be representative for Judaism & Jewry as a whole?

Sadly, Mr. Stephan's ahistorical and anti-historical analysis of the situation goes from bad to Vance-Netanyahu-Trump-Orban alliance politics, in a dangerously naieve piece of victim blaming: "I think that one of the reasons why the Near East Conflict does not come to a close is simply that from an Islamic standpoint it's hard to accept that they must relinquish a slice of the once conquered region." Ouch. "Must relinquish a slice": have you studied the recent historical sources, Mr. Stephan? Like books by and interviews with Israeli historian Benny Morris, darling of the German pro-political Zionist "Left"? Like the interview Morris gave in the Hebrew-language edition of Haaretz on 8 January 2004, under the title ‘Survival of the Fittest’, which was reprinted in English translation in March 2004 in the New Left Review: https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii26/articles/benny-morris-on-ethnic-cleansing Morris: "What the new material shows is that there were far more Israeli acts of massacre [during the Nabka; from c. 1947] than I had previously thought. To my surprise, there were also many cases of rape. In the months of April–May 1948, units of the Haganah [the pre-state defense force that was the precursor of the IDF] were given operational orders that stated explicitly that they were to uproot the villagers, expel them and destroy the villages themselves." And with even Zionist historians acknowledging "far more Israeli acts of massacre" than previously thought, and with the "many cases of rape"-sexual violence deployed strategically to crush psychologically the non-Jewish, and 95% Muslim population - will Mr. Stephan continue to assert the obsenity that if only the "Islamically minded" would get on with doing what they "must," and hand over a slice of the territory they've lived on for centuries, that all would be well, that the thousands of settler colonialists would throw their weapons into the river or the sea, and shake hands with the grandchildren of those they massacred, expelled, and raped? And with what motivation simply "relinquish" this land, if the IDF is going to take it anyway, with its incomparably superior force of strength. If this is what Nietzschean perspectivism does to you, they should warn the young against it.

Finally: as Stephan proposes that an "inner-Muslim education campaign" is necessary, let's begin with educating the resiliently pro-genocide of Muslim populations faction. The "war" did not start in October 2023, & Netanjahu and his cabinet did not decide to execute the genocide as a retaliation for Hamas' October 2023 terrorist attack; the genocide, backed by a big majority of Israel's population, is not caused by Hamas' anti-Semitism; the 3000 murdered Palestinian civilians in the 2008-2023 period, as documented by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA; https://www.ochaopt.org/data/casualties) is testament that the international community will certainly back a drawn out decimation of a Muslim population. Intellectuals, refusing to see the reality before their eyes, and in the pattern of classic, untreated neurosis, want to turn from this reality to the marginal issue of Muslim anti-Semitism. Providing useful cover. Should this go unchallenged?

friede-mit-dem-islam

December 22, 2025 10:46 AM

December 21, 2025 3:44 AM

Paul Stephan

Dear Rafael,

thanks a lot for your enlightening remarks.

Until recently, I was totally convinced that the famous anecdote of the marriage proposal(s) were right. It is actually repeated in every biographical text you find on Nietzsche.

When I wrote my text "Who Was Nietzsche?" for his blog, I did some research on Nietzsche and Lou Salomé on my own and I was also astonished by the fact that when you just have a look at the letters of Nietzsche, Lou, and Rée - the best and most reliable source we have on this matter - very little can be said about the actual nature of Nietzsche's and Lou's relationship, not even if it was romantic at all. But I still decided to repeat the story.

I now did some more research and I have to admit that I find your concerns highly plausible. Even the standard biographer Curt Paul Janz only gives Lou's account as a source when writing about the alleged first proposal. But why is she treated as a credible source? Just read the chapter on her in Carol Diethe's great book on Nietzsche's women!

I have taken up your concerns in a footnote to our most recent article on Nietzsche and fatherhood, mentioning you: https://www.nietzsche-poparts.ch/posts/vater-sein-mit-nietzsche

So yes: We all should definitely treat the proposal story with a lot more skepticism in the future. At least I will do it and maybe revise the passage about it in my "Who Was Nietzsche?" text.

Maybe Lou is not outright lying, however. I think it's at least possible that Nietzsche just spoke about his documents plans of a "terminable marriage" to her and she interpreted it as a proposal? But this just an ad hoc idea that would need more research to back it up.

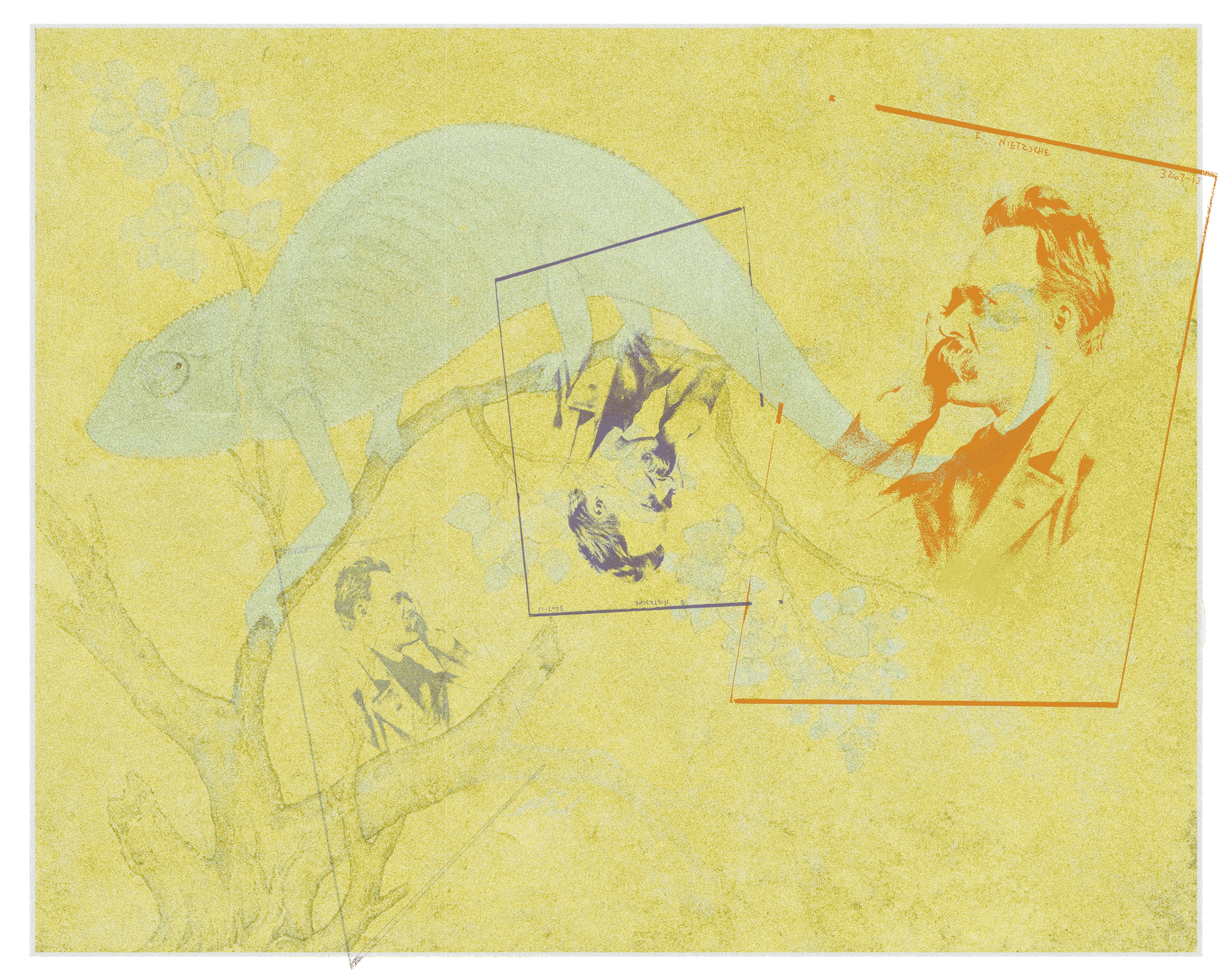

I would treat this anecdote a bit similar to the "Turin horse" event, however. Maybe, when it comes to stories like these, it's not so much about their empirical truths but about a deeper truth they transmit - maybe not so much about the empirical Nietzsche but about Nietzsche as an cultural archetype of modernity. It's obviously a modern repetition of the medieval story on Aristotle and Phyllis. The chauvinist free spirit, preaching independence and solitude, is overwhelmed and humbled by a young, intelligent woman and his own desire for love and maybe sexuality. And Nietzsche seems to present himself as a second Aristotle on the famous photograph!

The Turin horse, Lou, his illness, maybe syphilis - this all forms a modern myth, a myth of a tragic hero of individualism, overwhelmed by his bodily desires. Surely a myth according to Nietzsche's own taste. And we can choose to read it either as a tragedy or a comedy. Maybe we can find a way to indulge these orienting myths and treat them as fictions at the same time?

And I think that this myth is not that far from the actual truth. I'm not an expert on Nietzsche's biography but my current version of the Lou episode would go like this: He was looking for a young intelligent woman who would serve as his personal assistant, mainly as a reader (as is clearly document in a letter to Overbeck from that period). Then he met Lou and hoped to find this woman. Not so much a lover but a friend, helper, and maybe even student. His Tautenburg notes clearly demonstrate how inspiring this encounter with Lou was for him. But then, probably even in Tautenburg, he also developed a romantic and erotic attachment to Lou that she could not reciprocate and which made their friendship impossible in their own eyes.

But there's maybe another possibility: There's an interesting note in Lou's diary of her stay in Vienna in 1912/13 which hints into this direction - and as far as I know this is an authentic diary, not meant for publication. She recalls how her dialogues with Nietzsche touched upon sexual matters (in this case, the alleged connection between masochism and homosexuality), which led to both feeling embarrassed. (I mention it here: https://www.nietzsche-poparts.ch/posts/eine-neue-nietzsche-biographie) So maybe the reason for their break up was mainly that Nietzsche had the feeling that he had revealed too much about himself to her and felt ashamed - and she was embarrassed by Nietzsche's revelations. If this version was true, it would resonate very well with Nietzsche's later thoughts on friendship.

In any case: There's much more to be discovered!

Kind regards!

dionysos-ohne-eros

December 20, 2025 9:47 PM

December 20, 2025 12:33 PM

December 18, 2025 5:19 AM

December 17, 2025 3:02 AM

December 16, 2025 6:14 PM

December 16, 2025 5:31 PM

December 16, 2025 5:26 AM

December 16, 2025 2:10 AM

December 15, 2025 9:41 PM

December 15, 2025 8:24 PM

December 15, 2025 1:55 PM

December 15, 2025 6:41 AM

December 14, 2025 9:49 AM

December 13, 2025 6:54 PM

December 13, 2025 12:34 PM

December 12, 2025 10:45 PM

December 12, 2025 5:12 PM

December 11, 2025 10:06 PM

December 9, 2025 11:06 AM

December 7, 2025 7:19 PM

Пухов Антон Олегович Кронштадт

Кронштадт

auf-bedenklichen-wegen

December 5, 2025 8:41 PM

Paula

Ein großartiger Text, der zum Nachdenken über die Stellung der Frau in der heutigen Gesellschaft anregt.

barbarinnen---wenn-frauen-zur-gefahr-werden

December 4, 2025 3:12 AM

Rafael

Nietzsche never proposed marriage to Lou von Salomé. The idea that Nietzsche did this was refuted by Rudolf Binion, who released a biography of Salomé in the 1960s. The book has been ignored by Nietzsche scholars for reasons I can't fathom, but at least it was endorsed by Walter Kaufman. Binion shows that Salomé fabricated the proposals and gave an incorrect account of her relationship with Nietzsche. She maintained, for example, that she was the one who broke off the friendship with Nietzsche, when the letters that N. sent her prove just the opposite. After Nietzsche died, she began to claim that he had proposed marriage twice. Binion also says she did the same to a man she had met in Russia prior to getting to know Nietzsche, a married Dutch pastor who introduced her to the world of religious psychology. After this man died, she started to claim he had proposed marriage to her, and offered to leave his wife for her. It is also important to point out that not only Elizabeth Nietzsche but also Ida Overbeck explicitly denied that Nietzsche had proposed anything of that kind to Salomé. I know that Elizabeth's credibility has been called into question. But 100 years later, nothing of the sort has emerged regarding the Overbecks, who didn't even like Elizabeth.

My frank opinion is that Salomé's romantic fables were accepted so eagerly because, among male scholars, they're titillating as they provide a supposedly real life encarnation of the femme fatale archetype; and among female scholars, it offers revenge against Nietzschean misogyny and, among those who love his books, facilitates making peace with him for being so wrong about them.

dionysos-ohne-eros

December 3, 2025 5:41 PM

mma

"Sie kaufen Stocks, denn Reichtum ist das Ziel."- Warum nicht?! Haben kann das Sein unterstützen. Mehr Nvidia und Bitcoin in diesem Jahr gekauft und verkauft und dann mehr Zeit und Kraft für Camus und Co. - Ein kleines System in dem System Wirtschaft, das - wie so viele großartige andere Systeme (Bildungssystem etc) dabei hilft, zb das System "Philosophie" am Laufen zu halten und bei dem man, ganz nebenbei, durch seine Steuern auf die Gewinne und Geschenke viele andere Systeme unterstützt. Die Nischen leben, dank der Systeme. Das optimierte Funktionieren ermöglicht den Entwurf von Sinn, der das Leben zeitweise und immer wieder rechtfertigt. Danke Technik, danke Fortschritt, danke Kapitalismus.

der-sinn-ist-gefallen-doch-ich-traume-noch

December 2, 2025 11:43 PM

November 30, 2025 1:40 PM

November 28, 2025 5:53 PM

November 28, 2025 6:34 AM

November 28, 2025 5:04 AM

November 27, 2025 11:48 AM

Emma Schunack

Liebe Barbara Straka,

haben Sie vielen Dank für Ihre ausführliche Rückmeldung. Ich schätze Ihre Ergänzungen sehr.

Zu Ihrer ersten Anmerkung: In meinem Artikel beziehe ich mich auf die Friedrich-Nietzsche-Stiftung Naumburg– nicht auf die Nietzsche-Gesellschaft.

Auch bezüglich des Shops im Erdgeschoss des Nietzsche-Hauses danke ich Ihnen für die Einordnung. Da dort überwiegend Bücher erhältlich sind, habe ich ihn als „Bücherladen“ bezeichnet. Für Ihre zusätzlichen Informationen zur historischen Entwicklung des Kassenbereichs und zum heutigen Museumsshop bedanke ich mich herzlich.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen

Emma Schunack

nietzsche-und-cyborgs

November 27, 2025 10:10 AM

November 26, 2025 10:59 PM

November 26, 2025 12:04 AM

November 24, 2025 12:07 PM

Barbara Straka

Liebe Emma Schunack, vielen Dank für Ihren ausführlichen Bericht zum letzten Nietzsche-Kongress. Ich habe nur zwei Anmerkungen zur Richtigstellung: Die Nietzsche-Gesellschaft wurde nicht erst 2008 gegründet, sondern besteht bereits seit Anfang der 1990er-Jahre. Vor ihrem Umzug nach Naumburg befand sie sich in Halle/Saale. Bitte nochmal recherchieren, wann sie nach Naumburg umzog. Wichtig wäre hingegen, auf die später gegründete Friedrich Nietzsche-Stiftung hinzuweisen. Jedenfalls sind das zwei völlig verschiedene Körperschaften mit unterschiedlichen Gremien, Gründungsterminen und Aufgaben.

Meine zweite Anmerkung betrifft den Bücherverkauf im EG des Nietzsche-Hauses. Dieser "Laden" war vorher Kassenbereich, und man konnte schon zuvor dort einiges an neuer Nietzsche-Literatur kaufen. Vor zwei oder drei Jahren wurde der Raum als Museumsshop mit Neuerscheinungen und kleinem Antiquariat deutlich ausgebaut, aber es ist gegenüber der Museumsfunktion, die das Nietzsche-Haus seit seiner Wiedereröffnung in den 1990er-Jahren hat, sekundär. Seit April 2024 befindet sich eine neu eingerichtete interaktive Ausstellung in den Räumen, da kein authentisches Mobiliar erhalten ist, denn das ehem. Wohnhaus der Familie Nietzsche war im 20. Jahrhundert ein normales Mietshaus und zu DDR-Zeiten achtete man das "Erbe" nicht; das Haus war sehr verfallen. Alles nachzulesen in meinem Buch "Nietzsche forever? Friedrich Nietzsches Transfigurationen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst". Mit freundlichen Grüßen, Barbara Straka

nietzsche-und-cyborgs

November 23, 2025 6:36 PM

November 23, 2025 10:41 AM

November 22, 2025 11:55 PM

November 22, 2025 10:54 AM

November 21, 2025 4:18 PM

Emma Schunack

Ich verstehe es so, dass Gemeinschaft aktiv als Prozess des Gemeinsam-Werdens gelebt werden soll; dass ein Ineinanderfließen – Einverleiben – von Menschlichem zu Nichtmenschlichem, von Nichtmenschlichem zu Menschlichem, aber auch von Menschlichem zu Menschlichem bewusst realisiert wird. Die Bildung von Kollektiven ist dabei sowohl eine Form der Anerkennung als auch eine aktive Entscheidung für Zusammenschluss.

nietzsche-und-cyborgs

November 21, 2025 10:12 AM

November 21, 2025 1:22 AM

November 21, 2025 12:09 AM

November 20, 2025 2:18 PM

Elias Vogt

Frage: Was ist ein "Kollektiv von einem Cyborg", das / der ja schon selbst aus einer Vielfalt von mehreren Dingen besteht?

nietzsche-und-cyborgs

November 19, 2025 5:47 PM