Mythomaniacs in Lean Years

About Klaus Kinski and Werner Herzog

Mythomaniacs in Lean Years

Über Klaus Kinski und Werner Herzog

Werner Herzog (born 1942), described as a “mythomaniac” by Linus Wörffel, and Klaus Kinski (1926—1991) are among the leading figures of post-war German cinema. In the 70s and 80s, the filmmaker and the actor shot five feature films that are among the classics of the medium's history. They are hymns to tragic heroism, in which the spirit of Nietzsche can easily be recognized. From “Build Your Cities on Vesuvius! “will “Build opera houses in the rainforest! ”.

Truth has no future, but truth also has no past.

We want to, we will, we may, but we cannot give up the search for it.

(Werner Herzog, The future of truth, P. 110)

I wasn't great, I wasn't adorable. I WAS MOMENTARY, I WAS EPOCHAL.

(Klaus Kinski according to Werner Herzog, Everyone for himself and God against all, P. 92)

Nietzsche spent a lifetime on the subject of a “new myth” — the practice was provided by the congenial duo Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski, among others, several decades later. After a brief introduction to Nietzsche's vision of a new myth, it will be shown that cinema can be understood as a precise implementation of Nietzsche's vision of a tragic work of art that once again confronts people with a view of real grandeur. Herzog and Kinski's joint work marks, as will be shown in the second part of the article, a culmination of this development.

I. Zarathustra between cynicism and magic

For early Nietzsche the Birth of Tragedy It is clear: The biggest problem facing the West since the rise of the rational spirit in the form of Socrates is its loss of myths. The optimistic spirit first of Platonism, then of Christianity and finally of modern science and enthusiasm for democracy has the “myth-building spirit of music.”1 Silenced. This new spirit no longer knows tragedy, no more heroism. Only in Richard Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerke does the young philosopher see the hope of a revival of tragic heroism, a Dionysian worldview, which he harshly opposes the omnipresent modern rationality. He dreams of “overcoming knowledge by Myth-building powers”2 with Wagner as a revered “Mythologue and Mythopoet”3.

In the course of his general departure from Wagner and Wagnerianism, Nietzsche saw things much more complex just a little later. Under the influence of philosopher and psychologist Paul Rées, Nietzsche mutates into a “free spirit,” which “arbitrariness and confusion.”4 Sharply criticizes mythological thinking and shows time and again how much seemingly rational thinking is still entrenched in him. The critic of the Enlightenment becomes a relentless radical enlightener who takes the last blow: “The 'unfree will' is mythology: in real life, it is only about strong and weak Will. ”5

Of course, Nietzsche will always return to the big theme of his early writings, never completely shake off the dream of 're-enchanting the world. ' His Zarathustra mocks the mythless and ideless “last person”6 and appeals to a young man who has become cynical: “But with my love and hope, I implore you: Don't throw away the hero in your soul! Keep your highest hope holy! ”7

But Nietzsche is not himself “a cheeky, a mocking, an annihilator.”8When, looking back, he is proud of Human, all-too-human writes:

One mistake after another is calmly put on hold, the ideal is not refuted — It freezes... Here, for example, “the genius” freezes to death; a nook “the saint” continues to freeze to death; “the hero” freezes to death under a thick icicle; in the end, “faith,” the so-called “conviction,” also “compassion” cools down significantly [.]9

But Nietzsche doesn't want to stop there. The reckless negation is not intended to prevent a new affirmation, but to prepare it — to make it possible in the first place. In the dead of midnight, a new light should awaken: The flame of a new myth, whose exact shape Nietzsche is silent about, is supposed to be a myth of the future: “Premonitions of the future! Celebrate the future, not the past! Write the myth of the future! Live in hope! ”10

This hope is linked to the emergence of a new type of person, whom Nietzsche completely uncritically described as”barbarians of the 20th century”11 referred to. The modern person — “the most intelligent slave animal, very hard-working, basically very humble, curious to the point of excess, maniacal, weak-willed — a cosmopolitan chaos of affect and intelligence”12 — should be replaced by “a stronger Type”13 be replaced by their “will [s] to simplify, to strengthen, to the visibility of happiness, to dread, to psychologically nudity”14. The “blonde beast” is to be resurrected, about whom it is in the The genealogy of morality means:

At the bottom of all these noble races is the predatory animal, the magnificent wandering for prey and victory blonde beast Unmistakable; this hidden reason requires unloading from time to time, the animal must come out again, must return to the wild [.]15

Nietzsche sees the dialectic of nihilism and Renaissance at work here too: The general weakening and decadence will produce, on the one hand, an army of passive slaves who only thirst for new masters; hardened in the fight against modern slave morality, a new master caste will emerge victorious, which is also ready to take on this mission. In this respect, the following applies to him: “The adjustment For European people, this is the big process that cannot be hampered: it should be accelerated even more. ”16 The extreme, most thorough, radical nihilism should also turn into its opposite in this respect: “Midnight is also noon”17.

Nietzsche has therefore never given up the dream of a new myth; it has only become more complex, more complex. The remythologization, yes: rebarbarization, of the world can only succeed if it no longer harshly opposes modern irony and skepticism, but uses it as a means. The skeptical insight that there are no more truths, no more pillars of world orientation — as in the case of Zarathustra's “Shadow.”18 — a reason for despair but for the greatest joy, as it enables the creation of new values, new wisdom, new myths precisely on the basis of that skepticism: “[E] ndly the horizon appears clear to us again, set itself that it is not bright, finally our ships may sail again, sail at any risk, every risk of the discerning person is allowed again, the sea, our The sea is open again, perhaps there has never been such an 'open sea' . ”19 And Nietzsche confidently calls for departure: “Get on the ships, philosophers! ”20

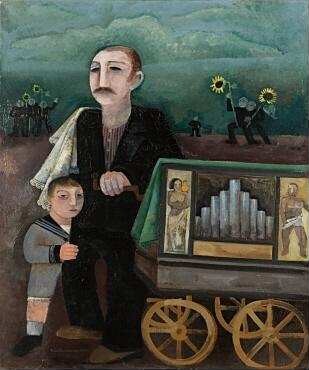

II. Cinema as a place of worship

Numerous performers have followed Nietzsche's appeal — but, unsurprisingly, interpreted it in very different ways. Even more than philosophers, Nietzsche has inspired artists not to be swayed by moral and rationalistic prejudices in their work, but to follow their instincts and imagination. Since the youth movement around 1890 at the latest, we have been dealing with ever new waves of remythologization, which repeatedly find an advocate in Nietzsche. While Hegel around 1800, arguing against Romanticism, which was similar to Nietzsche, called for people to accept that tragedy, heroism and individualism had just come to an end, and to submit to the state and its bureaucracy,21 Nietzsche and his colleagues repeatedly hurl a defiant “no” at him. The story isn't over yet: “There are so many dawns that haven't lit up yet. ”22

Of all the arts, cinema is the most suitable way to give this' Reconquista 'an aesthetic form. Wagner's operas can be interpreted as direct anticipations of film and it is no coincidence that his compositional methods — such as the use of leitmotifs and the primacy of mood over harmonic logic — are almost ubiquitous in film music. The powers of all arts are combined and bundled here to literally captivate the audience with all their senses and take them away to another world. Adorno and Horkheimer observed this historically new fascinating power of film as early as the Second World War and saw Wagner's operatic art as a direct precursor to the manipulative “cultural industry.”23

If you still wanted to argue like this today, you would put yourself in the unpleasant situation of a monk who, around 1650, would have warned of the dangers of printing and would have praised the faded beauty of the handwriting. Today would be more the magic of the classic cinema hall versus the isolated binge watching To defend against a home tablet. The great era of film and its myth-making power is probably over. Real tragic stories have been replaced by stage-produced film series, which draw their 'shine', if at all, from overwhelming technical effects and barely allow a big moment that is not immediately returned by the obligatory Comic Relief would be leveled. Each of these strips is obviously calculated to include as many as possible sequels and spin-offs allow and maximum merch-to be fit. Serious artistic engagement with interesting topics was systematically based on a crude mixture of commercial calculation and the effort to signal, depending on the target group, Wokeness or 'realness'replaced. In its weak moments, as it was called in the work of the exiles committed to the principle of despair, cinema may have been “mass fraud” — today it is a means of blatant mass delusion.

III. Lonely giants

It was only a few decades ago that it was different. The cinema was a magical place, a last bastion of heroism in a completely “managed world,” as the Adorno and Horkheimers critically described post-war society in the spirit of Nietzsche. Not only the auteur films of avant-garde cinema, but also the popular productions, there was an authentic magic, the effect of which was not only obfuscating and numbing, but also inspiring and in some cases perhaps even enlightening. Cinema not only compensated for the loss of the stolen individuality, but also encouraged people not to simply put up with it. The cinema answered Nietzsche's prophetic question “[W] o are the barbarians of the 20th century? ”24 Both defiant and trivial: Here, on the screen.25

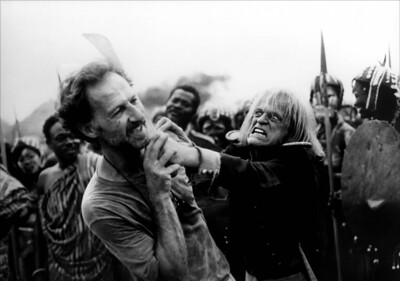

The joint work of Klaus Kinski and Werner Herzog is located at the interface between author and popular film, in the midst of this classic period of cinema. The actor and the universally responsible “filmmaker” acting in Wagner's tradition, who had already met in Munich in the 1950s26 produced in that golden age of feature films with Aguirre, the wrath of God (1972), Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night (1979), Woyzeck (1979) — probably the best film adaptation of Büchner's material that exists —, Fitzcarraldo (1982) and Cobra Verde (1987) five highlights of post-war German film, which, apart from Cobra Verde, are undoubtedly masterpieces.27 There the calm, sober head, there his quick-tempered, wild organ, both possessed by the same delusions of grandeur: creating the perfect film, giving shape to the tragic myth on the screen. We're actually not dealing with an “actor” or a mere “filmmaker.” “I'm not playing, that's me”28, Kinski announced and Herzog continued: “He wasn't an actor. [...] He was the only genius I met. ”29 He himself, however, announced: “My films are what I am”30. They are artists who claim to be identical with their work. There is no irony, no skepticism, no calculation here — there is only the absolute will to be authentic, to sacrifice for the complete work of art.

Even visually, Kinski is predestined to play the “blonde beast” over and over again, actually playing the same role, himself, playing the insane psychopath in different facets in the fight against the modern world: “With Herzog, Kinski is the person who goes to the extreme, at the edge of the world, perception, language and life. ”31

The saga begins with Aguirre. This is where the archetype makes its first appearance. The film tells of a Spanish conquistador's desperate search for the golden land of El Dorado. With growing despair, the title hero, who has acted as a choleric dictator from the start, becomes more and more insane. He whips his followers across the Amazon. They die or are killed. In the end, he is left alone. A squirrel monkey is his last companion. The only one is driven along the stream with his remaining property, little more than a capsizing raft. The fury of Aguirre is unforgettable, the pictures shot with great effort of crossing the Andes at the beginning of the film and the rainforest, unforgettable is the final monologue in which Aguirre promises himself a bright future. The Dionysian myth is beamed onto the screen in the spirit of early Nietzsche and therefore ends with the demise of the hybrid hero. Everything in the film consistently goes down the drain, better: down the river, but he firmly adheres to his dream of fabulous wealth and endless fame until the very end.

However, it may mark the peak among the highlights Fitzcarraldo.32 Kinski doesn't play one, he is The opera enthusiast Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, known as Fitzcarraldo, who is obsessed with the crazy dream of building an opera house in the middle of Peru's rainforest, in the city of Iquitos, struck by rubber fever. He sets off on a boat trip in the middle of the jungle to buy rubber to finance this plan — but to do so he has to cross a mountain with his steamer. Through his charisma, he is able to convince the indigenous people living there to help him. He achieves the unbelievable. After a few accidents, however, Fitzcarraldo has to be content with having a single opera performed himself on the deck of the damaged ship.

Who watched the documentary My favorite enemy (1999), produced by Herzog himself, gets the impression that the film tells its own story. Herzog himself notes in his diary during filming that “my task and that of the character have become identical.”33. During the two-year adventurous ordeal, for the most part in the middle of the rainforest, several of Herzog's employees almost died, there were repeated conflicts with the indigenous people involved, and Kinski's choleric tantrums further complicated the situation. Apart from the financing difficulties for this mammoth project.

The battle of the white man with the wilds of the rainforest — that is also the defining theme of Aguirre and Cobra Verde. In the latter, however, it is repeated, in accordance with the famous formula of Marx,34 Tragedy as a farce. Brazilian bandit Francisco Manoel da Silva is sent to Africa by a sugar baron to acquire new slaves there. There, da Silva takes on a local king and overthrows him with the help of an army of half-naked black Amazon warriors drilled by him. Kinski as a sadistic leader of an army of bare-breasted African women who captivate them solely by his exuberant masculinity: A man's imagination is turned into the absurd in such a way that the film, in the absence of any ironic break, simply seems involuntarily funny. After all, Herzog succeeded in creating what is perhaps the most grotesque, not intended as such, image in film history. It is only logical that the cooperation between the two ended afterwards: The material had exhausted itself, the inadequate had already become an event.35

Separated from each other, neither Kinski nor Herzog ever succeeded in rebuilding this zenith of their work. Kinski died a few years later and left behind the film Paganini (1989), for which he himself took on the role not only of the title hero, but also of the screenwriter and director. A barely visible work in which he plays himself one last time, the eccentric “original genius” who captivates women into sexual ecstasy through his demonic violin playing.36

Herzog continued to create major films such as the documentary Grizzly Man (2005) and Queen of the desert (2015), which, however, only vary the theme already set — rebellion against the wilderness and failure. The latter film is remarkable because it is now a white woman who is moving to the Middle Eastern desert. It is based on the real life story of the protagonist Gertrude Bell, a young British woman who flees the narrow world of Victorianism to live a lonely life as a desert researcher. Unlike her male counterparts, however, she does not act brutally and exploitatively, but learns the languages of the natives and criticizes British imperialism. A successful memorial to an emancipated woman of fin de siècle? Or not a sexist orientalist male fantasy that repeatedly descends into kitsch? In any case, the film is no longer as convincing as it is still Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre actions. The obvious question “Where are the barbariansinside? “— Wouldn't a 'rescue of the Occident' be the responsibility of emancipated women rather than men, who, like Nietzsche, are far too entangled in patriarchal structures to become truly free spirits?37 — in any case, remains open.

IV. Genius and Kitsch

But anyone who wants to create a new myth in the modern age must be constantly on the line between kitsch and grandeur. Nietzsche's texts also often move on her — and even exceed them. He saves himself through the permanent use of ironic breaks and withdrawals. Herzog and Kinski are probably turning from size to kitsch again and again because they completely dispense with these stylistic devices. Queen of the desert The orientalism of the end of the 19th century does not simply quote, the film celebrates it, it revels in these long-stale dream worlds in a completely unironic way and it depends on the viewer whether he likes to get involved with it or not — a successful production would not require such a decision at all. In Cobra Verde Approving identification with what is shown would even require the complete abandonment of aesthetic judgment and self-deception; greatness is shown in great failure.

The distance to Nietzsche, who is actually much closer to historical German Romanticism in this aspect of all things, is reflected not least in the fact that he does not play a major role in either Kinski's or Herzog's frame of reference. Kinski, who celebrated his breakthrough around 1960 as a reciter of major literary works,38 Read only a few poems by Nietzsche over and over again with the same powerful, creaky trained actor voice. There is no irony here, no withdrawal, just pure pathos. Sometimes Kinski's voice turns into screaming, screeching, screeching.39 Here, too, involuntary comedy, which shows that he may have read little about Nietzsche apart from those poems.

Neither in the relevant Kinski biography by Peter Geyer nor in that of Christian David is Nietzsche mentioned even once. In Kinski's own autobiography I need love Almost any reference to any philosophers is missing, but there is even more talk of sparkling women's stories. However, this also applies to Herzog, who in his memoir Everyone for himself and God against all It doesn't seem as though reading any philosopher has decisively shaped his life path.

In the case of Herzog, this is certainly surprising, as he propagates a thoroughly Nietzschean view of the world in his films, which he has repeatedly set forth explicitly in numerous writings, in particular in his book of essays worth reading The future of truth — but without mentioning Nietzsche in a decisive place. Rather, it is noticeable that, in contrast to many other philosophers, he just not mentioned.40

As Kristina Jaspers and Rüdiger Zill also points out in the preface to their anthology Werner Herzog. At the borders note and convincingly substantiate them on the basis of a few Nietzsche quotes,41 Herzog's view of cinematic truth has strong references to Nietzsche. It circles, as it is contained in that volume, for example Minnesota Declaration from 199942 explains, therefore, that the usual 'realistic', factual documentary is missing the actual reality right now. This applies with the aim of “enlightenment”43 of the viewer, using completely different methods: “In film, the truth lies deeper and there is something like poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and difficult to grasp; it can only be learned through poetry, invention, stylization.” (ibid.) Herzog is concerned with the authenticity of the self-experienced, directly experienced as opposed to the simply prechewed and known. In a few words in the style of a Nietzsche sentence: “Tourism is sin, traveling on foot is virtue.” (ibid.)

Just like in the Birth of Tragedy For Herzog, reality is therefore not reflected in ordinary everyday experience, but in crossing borders and excess — and to represent them requires mythical images, a tragic hero of the likes of Kinski, in whose failure the audience learns a deeper existential truth.

Like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, this truth is gloomy, normally, i.e. without an aesthetic veil, hard to bear. For him, it is particularly evident in the confrontation with untamed nature, whose epitome is the rainforest. This is particularly in Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo Almost the true protagonist of the films. Herzog's artistic greatness is particularly evident in the way he stages the landscape in these films. Even more than the music, it is here the Ur—Wald The sounding board on which the Dionysian myth can unfold. He gives birth to the hero and devours him again, even if he gives him in Fitzcarraldo — perhaps for this reason a more successful film than Aguirre — in the end, cunning cheats, triumphant in failure, laughing in doom.

This understanding can be found in particular in the mentioned documentary My favorite enemy remove. For Herzog, the rainforest is an anti-idyll that shows the brutality and absurdity of being. In manifesto It says accordingly: “The moon is dull and stupid. Nature doesn't call or talk to anyone, but occasionally a glacier farts. Just don't listen to the 'Song of Life. '” (p. 164) And:

Life in the deep sea must be hellish. A limitless, merciless hell of constant danger. So hellish that some species — including humans — have crawled out of it in the course of evolution and have escaped to the dry land of a few small continents, where the lessons continue in darkness.44

And the same goes for Kinski. This is how Peter Geyer leaves the band Kinski with a quote from I need love start:

Wind force twelve. No one is outside. I sit on the rock by the sea, from which I always look at the departing ships. The surf rages over fifteen meters high. The storm whips the salty spray all the way to my face. The thunder causes the sky to collapse and the lightning to shake me. I've never been happier than I've ever been in my life.45

Both attitudes — warning against Dionysian primal truth and ecstatic dedication to it — are also found in Nietzsche.

But even though it is the landscape photo rather than the music that acts as a Dionysian sounding board in Herzog's films, it still plays a key role in his self-image: “In my films, music is never an event in the background, but transforms the images into elementary visions. ”46

This also puts us right in the middle of the program of Birth of Tragedy And it is hardly surprising that Herzog shares his love for the 'great opera' of the 19th century with his fictional character Fitzcarraldo and the philosopher. Herzog is also an opera enthusiast and has staged several operas, including some by Wagner. For him, the opera is almost even more “realistic” (in his sense) than the film:

The feelings of opera are absolutely condensed, but they are true for the audience because the power of music makes them come true. The feelings of grand opera are always like axioms of feelings, like an accepted truth in mathematics that you can no longer reduce, concentrate, explain.47

Nietzsche's absence is all the more surprising since Herzog and Kinski are trying to resurrect the 19th century.48 Whether in her films or in her other work: Time and again, the 19th century is a central point of contact. This is no accident, as it was the heyday of modern individualism. The bureaucracy of the modern state was not yet complete, the market still allowed real competition before monopoly capitalism, the world was not yet managed. There was still unmapped territory, both literally and figuratively, where isolated heroism could ignite.

But it is precisely in this “big gesture” that the limitations lie — that of the more reflective duke less than that of Kinski. Anyone who just enters their name on YouTube quickly realizes that in his permanent desire to market himself as a rebellious 'original genius' of the 19th century, he crossed the line not only into kitsch, but also into ridiculous and embarrassing. Because you realize all too quickly that he is an actor after all and this is a production based on specific effects, never pure authenticity. As Herzog notes in his memoirs, the voice, the entire style of Kinski, is the product of days of excruciating exercises49: He wasn't born as Klaus Kinski — in the very literal sense of the word, because his birth name is less sonorous Klaus Günter Karl Nakszynski — he set out to do so.

Nietzsche and Herzog reflect that the relationship between masquerade and authenticity is not so simple, that authenticity necessarily always goes hand in hand with masking — in his anachronistic reenactment The cult of genius of the 19th century escapes Kinski. Perhaps this is the real tragedy of his life. He didn't always just play so much yourself — he played Always just yourself. He merged so much with his own role that he was left with no self at all. It is precisely this obvious lack of reflection that awakens foreign shame when you look at some of his interviews: Unable to save himself in irony like Nietzsche, he tries cynicism and insists, in all seriousness, that he is not interested in the artistic value of a film, it is only about the amount of the fee for him.50

In fact, Kinski's gigantic filmography of over 130 films comprises a good portion of trash films to erotic films of dubious level. Since he couldn't handle money, he was plagued by monetary concerns throughout his life and was therefore willing to shoot junk films when the pay was right. But he also rejected film offers that did not appeal to him artistically. The production as a cynic affects But undoubtedly more “authentic” than truly honest self-disclosure — and it gets Kinski in particular more attention.

But tragically, all of this does not seem to have been calculated for him. He seems “crazy” insofar as he has lost himself in the role of a madman, inasmuch as he really believes that he is — a cynical psychopath — without actually being one. His excentricity on display should prove this to himself and to the world time and again: I am not like you, I am a person of the 19th century. He would not be an authentic person, but an inauthentic person par excellence, one in which self-image and reality of life, as with everyone, not only diverge but diverge to such an extent that the delusional self-image becomes second nature — a 'nature' whose status, of course, remains precarious and which therefore has to be re-staged, reconfirmed and proven anew at any moment.

However, this does not involve Kinski's tremendous driving energy. His compulsive self-alienation suggests an early childhood trauma that haunted him for a lifetime and not only made him a unique actor and feared choleric, but also culminated in drug excesses, several psychiatric visits and addictive sexuality. I need love It is not by chance the title of his autobiography: He sought love, but since the experience of real love would have meant leaving the role, which was impossible for him, he was only able to seek a substitute for love — recognition, power, sexual enjoyment without fulfillment, drug intoxication in order to somehow avoid the inner emptiness. What he lacked was the experience of real resonance, of real love: “If only the sea would be a bit quieter! I'm not afraid, it's too huge, too overwhelming. Almost as protective as a mother. Like love. ”51

A fate that is not only pitiful, but of course also led to Kinski behaving just as recklessly and violently as his film roles, even in his 'real life, 'when you are allowed to speak like that. In recent years, the revelations surrounding the sexual and emotional abuse of his two daughters — which is even hinted at in his autobiography — have been particularly striking.52 This dark side of his actions cannot be excused even by Kinski's own traumatization, which he passed on directly through his despicable behavior towards them.

But Kinski's failure also has to do with the fact that he lacked a real social sounding board. Georg Seeßlen attributes Kinski's — tragic — ridicule primarily to the fact that he never met with a right response in the bourgeois, small-minded West German post-war society, as “the sad ghost of the German superman.”53 had to remain nothing more than an admired but at the same time despised nerd, an individual archist in the spirit of Stirner,54 In which, however, there is also a collective fate; Kinski as “[e] in the German archetype, an archetype of the German, and always above all their parody.”55. In probably no figure of the German post-war period intersect such 'genius' and madness, kitsch and ridicule56, “size” and triviality — and that probably actually makes Kinski a kind of “super-German,” just like Herzog with his accent in the USA as Edgy German is celebrated. — All this causes great discomfort, but in the sense of Nietzschean self-expression, it would probably be important not to avoid this gruesome reflection, but to recognize it as part of one's own self; especially in order to be able to embark on a different path.

V. The anti-robot

In spite of everything, I don't want to lose my enthusiasm for the work of Kinski and Herzog. Without ambitious people like them, the world would be worse than it already is. We may think they are crazy and morally condemn their personal behavior — in the end, we must admire the greatness of their work and should use it as an incentive to produce something great ourselves, even though we may not want to be so reckless in doing so. Or is at least a certain recklessness towards oneself and others not necessarily part of the work?

In any case, shortly before his death, Kinski received a last anonymous letter from a fan, published on the back of the first edition of his autobiography I need love, which summarizes well what remains of Kinski. It is hardly necessary to mention that almost every sentence can be interpreted as an allusion to Nietzsche:

... They are the opposite of the robot, the programmed computer, the metal structure and the reinforced concrete... Yes, you live and breathe like a free animal... you are the human-animal, the animal that you have denied in order to submit to the machine... You are the vibrant life that we have forgotten... You have the lion's mane, the eagle's gaze, the wolf's smile, the harsh beauty of the raging sea and the wild ugliness of melting lava, blood-red, like a bleeding heart, on the slopes of a gloomy volcano... You are the man from whom You'll talk again and again, but that no one can remember anymore... the legend... of being human...57

“Build your cities on Mount Vesuvius! ”58, Nietzsche famously recommends. Whether Herzog and Kinski read this or not — they certainly lived it59 and in doing so made the world richer by some inspiring big myths. “Look for Eldorado! ”, one would like to add: “Build opera houses in the rainforest! ”

sources

Adorno, Theodor W. & Max Horkheimer: Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical fragments. Frankfurt am Main 2006.

David, Christian: Kinsky. The biography. Berlin 2008.

Geyer, Peter: Klaus Kinski. Frankfurt am Main 2006.

Ders. & Oliver A. Krimmel: Kinsky. Legacy, autobiographical, stories, letters, photographs, drawings, lists, private matters. Hamburg 2011.

Hegel, George William Frederick: Principles of the Philosophy of Law. works, Vol. 7. Frankfurt a. M. 1986.

Ders. : Lectures on aesthetics, Vol. II works, Vol. 14 Frankfurt a. M. 1986.

Herzog, Werner: The future of truth. Munich 2024.

Ders. : Conquering the useless. Munich 2013.

Ders. : Everyone for himself and God against all. Frankfurt am Main 2024.

Jaspers, Kristina & Rüdiger Zill (eds.): Werner Herzog. At the borders. Berlin 2015.

Kinski, Klaus: I need love. Munich 1995.

Ders. : Paganini. Munich 1994.

Kinski, Poland: Children's mouth. Berlin 2013.

Presser, Beat: Kinski. Berlin 2000.

Worffel, Linus: Mythomaniac Werner Herzog. Work — effect — interplay. Bielefeld 2024.

footnotes

1: The birth of tragedy, paragraph 17.

2: Subsequent fragments 1872 19 [62]. See also another programmatic fragment from the same period (link).

3: Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, paragraph 3.

4: Human, all-too-human I, Aph 12.

5: Beyond good and evil, Aph 21.

6: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 5.

7: So Zarathustra spoke, From a tree on a mountain.

8: Ibid.

9: Ecce homo, Human, all-too-human, paragraph 1.

10: Subsequent fragments 1883, 21 [6].

11: Subsequent fragments 1887 11 [31].

12: Ibid.

13: Ibid.

14: Ibid. Our essay prize this year is dedicated to the precise interpretation of this fragment and its current relevance (link).

15: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 11.

16: Subsequent fragments 1887 9 [153]. For this motif, see also Beyond good and evil, Aph 242.

17: So Zarathustra spoke, The Nightwalker Song, paragraph 10.

18: See my corresponding remarks in the second part of the essay Between Monsters and Abysses(Link).

19: The happy science, Aph 343.

20: The happy science, Aph 289.

21: See in particular Hegel's exclamations of the “end of art” in comedy (cf. Lectures on aesthetics Vol. II, p. 219 f.). Hegel's anti-individualism is most blatantly expressed in Principles of the Philosophy of Law, where he unbridled the slaughter of individuals for the civil service state: “The courage of the animal, the robber, the bravery for honor, the chivalric bravery are not yet the true forms. The true bravery of educated peoples is the willingness to sacrifice in the service of the state, so that the individual is only one among many. The important thing here is not personal courage, but classification into the general.” (addition to § 327; p. 495)

22: That is the motto of Morgenröthe (link).

23: Cf. Dialectic of Enlightenment, PP. 128—176.

24: Subsequent fragments 1887 11 [31].

25: Waiting for the Barbarians Accordingly, the title is one of the chapters of Herzog's autobiography (cf. Everyone for himself and God against all, pp. 260—264) and also the title of a novel by J. M. Coetzee, which Herzog wanted to film temporarily (see ibid., p. 260).

26: Even then, young Kinski stood out for his eccentric behavior and in particular his outbursts of anger. Cf. the vivid description of this period in Herzog's autobiography Everyone for himself and God against all (PP. 92—95).

27: Herzog, who had a proud filmography of 79 films in 2024, is one of the few internationally successful German filmmakers (see Linus Wörffel: Mythomaniac Werner Herzog, P. 9).

28: Quoted by Wörffel, Mythomaniac, P. 179.

29: Beat Presser: Kinski, P. 17.

30: Quoted by Wörffel, Mythomaniac, P. 179.

31: Georg Seeßlen in Presser, Kinski, P. 35.

32: According to Wörffel, the film also represents the zenith of both Kinski's fame and Herzog's recognition in Germany (cf. Mythomaniac, P. 9).

33: conquering the useless, p. 158 (entry dated 18 February 1981).

34: “Hegel noticed somewhere that all major world historical facts and people happen twice, so to speak. He forgot to add: one time as a tragedy, the other time as a farce.” (The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte; link.)

35: “According to Klaus Kinski, after Woyzeck, 'everything was said. ' There is something to it,” notes Seeßlen accordingly (in Presser, Kinski, p. 35), even though afterwards Fitzcarraldo came. On the corresponding negative contemporary reception of the film, see Peter Geyer: Klaus Kinski, p. 107. In Herzog's more recent texts, there is a general tendency, very often about Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo to talk about him, but hardly ever about him.

36: “This Satan who dominates the horny dreams of the female sex” quotes the cover of the film book in a lurid but authentic way (see Klaus Kinski, Paganini). Appropriately, at the end of the book, the publisher promotes various “erotic novels and stories” with titles such as rainforest. Chaos of Desire.

37: Interestingly enough, one of Kinski's first major successes as a stage actor was a “rock role”, as was still common back then, in fact, he played the female protagonist of Jean Cocteau's one-person play La voix humaine (see Peter Geyer & Oliver A. Krimmel: Kinski, PP. 32—39).

38: After a cult around him in the 1950s as Enfant Terrible of German theatre, he reached one million viewers with his readings in 1961 (see Geyer & Krimmel, Kinski, p. 7), he was “Germany's most successful [r] reciter with an audience of millions and 32 speaking plates between 1959 and 1962” (ibid., p. 73).

39: This is particularly clear in his reading of An den Mistral And also from After new seas. These poems are included on the CD's Kinski talks, “Hauptmann & Nietzsche” and Klaus Kinski: Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Baudelaire, etc.

40: I actually didn't come across a single mention of it. In the presentation About the Absolute, the Sublime and Ecstatic Truth (in: Kristina Jaspers & Rüdiger Zill: Werner Herzog. At the borders, pp. 165—174), for example, he instead also talks about Blaise Pascal and Homer, who were also appreciated by Nietzsche. In The future of truth A list of great thinkers on the subject of the book Nietzsche of all things is missing (see p. 23).

41: Cf. p. 9 — this is, of course, the only mention of the philosopher in the entire volume!

42: Cf. p. 163 f.

43: Ibid., p. 163.

44: Ibid.

45: P. 4.

46:Everyone for themselves, P. 308.

47: Ibid., p. 310. See also his remarks in Jaspers and Zill, Werner Herzog, p. 170 f. Herzog's love for opera was apparently only awakened by this film and not vice versa. According to his own admission, he had never seen an opera from the inside before filming Fitzcarraldo (see Geyer, Klaus Kinski, P. 105).

48: “I consider the 20th century as a whole to be a mistake,” Herzog writes accordingly in Everyone for himself and God against all (P. 124).

49: Cf. Everyone for themselves, P. 94.

50: Cf. Seeßlen in Presser, Kinski, P. 32.

51: I need love; cited by Geyer & Krimmel, Kinski, p. 382 ff.

52: And also in Paganini Rape and affection for underage women and girls are addressed quite openly. — According to her autobiography, he abused his older daughter Pola Kinski Children's mouth Sexually and raped her several times; his younger daughter was more likely to be the victim of emotional abuse by him, even though he also approached her in an unacceptable way.

53: In: Presser, Kinski, P. 31.

54: See ibid., p. 31 et seq.

55: Ibid., p. 32.

56: A ridicule that comedian Max Giermann in particular has shown in his Kinski parodies in recent years.

57: Geyer & Krimmel, Kinski, p. 71 (original omissions).

58: The happy science, Aph 283. See also the detailed interpretation of this passage by Natalie Schulte on this blog (link).

59: Several of Herzog's films are even dedicated to the topic of “Encountering the Volcano”, most recently The inner glow (2022).