#

friendship

From Denier to Conspiracy Theory to Ghosting

Nietzsche and the Social Upheavals Caused by Today's Widespread Resentment

From Denier to Conspiracy Theory to Ghosting

Nietzsche and the Social Upheavals Caused by Today's Widespread resentment

After Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann has already dealt with Nietzsche's concept of resentment in two articles on this blog (here and there), he now addresses the question of how it can be applied to the current social situation.

His thesis: The current political landscape is characterized by many divisions based on resentment. They are due to the weaknesses of their own arguments. This is how critics are defamed as “corona” or “climate deniers.” The objections are often branded as conspiracy theories. You can't ask 'Cui bono?' anymore. Or you break off contact without comment to protect yourself. This is not only in line with Nietzsche's understanding of resentment in many places, precisely because he himself is not free from it, but is looking for ways out of it.

“What is the topicality of Nietzsche's analysis and critique of 'resentment'?“ is also the question of this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing, in which you can once again win up to 750 Swiss francs. The closing date for entries is August 25. The complete tender text can be found here.

If you'd rather listen to the article, you can find an audiovisual version on the Halcyonic Association YouTube channel, read by the author himself (link) and a listening-online version on Soundcloud (link).

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Nietzsche certainly did not have any children and is also not particularly friendly about the subject of fatherhood in his work. For him, the free spirit is a childless man; raising children is the task of women. At the same time, he repeatedly uses the child as a metaphor for the liberated spirit, as an anticipation of the Übermensch. Is he perhaps able to inspire today's fathers after all? And can you be a father and a Nietzschean at the same time? Henry Holland and Paul Stephan, both fathers, discussed this question.

We also published the complete, unabridged discussion on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy YouTube channel (Part 1, part 2).

Abonimably Married, With Children

Nietzsche as the Wagners' house friend in the “Tribschen Idyll”

Abonimably Married, With Children

Nietzsche as the Wagners' house friend in the “Tribschen Idyll”

Richard Wagner lived on Lake Lucerne for six years. In April 1866, he was able to rent the Landhaus of the Lucerne patrician family Am Rhyn, which had been built in a beautiful scenic location on the Tribschenhorn. Nietzsche had been a frequent guest there at that time and enjoyed the family connection. For him, it was an episode that shaped him throughout his life, so that the confrontation with Wagner — in its entire range from unconditional adoration to rude rejection — can perhaps even be regarded as the heart of his thinking. Today, the building houses the Richard Wagner Museum. His current special exhibition focuses on the composer's anti-Semitism.

On Dubious Paths ...

An Outline of Nietzsche's Concept of Wandering

On Dubious Paths ...

An Outline of Nietzsche's Concept of Wandering

Perhaps it is Nietzsche's main philosophical achievement that he described thinking as a process that happens in person. For him, reflection is a cooperative tension of body and mind. The mind is grounded in the nervous cosmopolitanism of the body. Nietzsche's conversion of Christianity: The flesh becomes word. This shows thinking in gestures. The following is intended to provide a sketch which indicates the main types of these reflexive gestures. This is intended to illustrate what it means when Nietzsche repeatedly describes himself as a wanderer. An intellectual tour that leads from standing and sitting as basic modes of traditional philosophy to walking, (out) wandering and halcyonic flying as Nietzsche's alternative modes of liberated thought and life.

“Peace Surrounds Me”

An Unusual Christmas Message

“Peace Surrounds Me”

An Unusual Christmas Message

In our last article before the break at the turn of the year, Paul Stephan explores a Close reading A remarkable aphorism of Nietzsche, in which he expresses himself with the famous Christmas blessing “Glory be to God in height and peace on earth and to people! “discusses. As when unwrapping a gift that has been covered several times, he tries to reveal the different layers of meaning in this text in order to make Nietzsche's exact positioning clearly stand out. The reader may decide for himself whether you end up holding a glowing truth in your hand or the box remains empty. In any case, we wish all our readers with Nietzsche: “Peace on earth and good pleasure for each other! ”

A Philosophical Serenade About Grayness

A Summer Evening with Sloterdijk at Gütchenpark in Halle

A Philosophical Serenade About Grayness

A Summer Evening with Sloterdijk at Gütchenpark in Halle

One of the most important philosophers of our time, Peter Sloterdijk (born 1947), visited Halle at the beginning of July. The thinker, who was heavily influenced by Nietzsche, shared his thoughts about “gray” there and impressively showed the heights to which philosophy can rise.

“A Gods’ Table for Divine Dice Throws and Dice Players”

Nietzsche's Superman Visits the Start-Up Scene

“A Gods’ Table for Divine Dice Throws and Dice Players”

Nietzsche's Superman Visits the Start-Up Scene

Nietzsche's superman is dead. Hardly anyone can do anything with this obscure idea anymore. You'd think so. And yet, in the current startup environment, you encounter numerous set pieces from Zarathustra's promise. What is it all about? — On the occasion of Nietzsche's 180th birthday, Natalie Schulte dedicates herself to this peculiar continuation of one of the philosopher's best-known concepts. A plea for taking a closer look at Nietzsche's idea despite its past and present misinterpretations.

Editor's note: We have translated longer English quotations into German in the footnotes ourselves.

In the House of Semblance

Preludes on the Connection Between Architecture and Thought in Nietzsche with Constant Reference to a Book by Stephen Griek. A Review

In the House of Semblance

Preludes on the Connection Between Architecture and Thought in Nietzsche with Constant Reference to a Book by Stephen Griek. A Review

A fruitful method within philosophy can be addressed seemingly minor, everyday topics. For example, the relationship between thinking and architecture, as this text is based on the newly published book Nietzsche's architecture of the discerning By Stephen Griek tried to show. With Nietzsche in mind, according to Michael Meyer-Albert, protecting a dwelling — both literally and figuratively — from the chaos of reality is essential for a successful world relationship. He neglects this in Greek's post-modern approach, which aims at maximum openness and wants to replace clear spatial structures with diffuse nomadic networks. Architecture as an art of non-violent rooting thus becomes unthinkable; the “house of appearance” that supports human existence collapses.

The Artist as Egomaniac

A Reckoning?

The Artist as Egomaniac

A Reckoning?

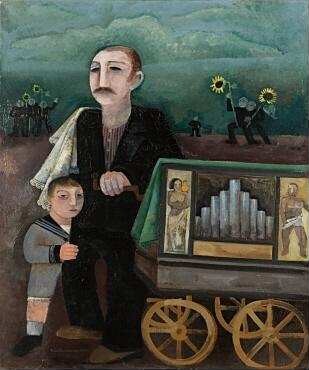

Artists often do not come off well in Nietzsche’s work. They represent the prototype of the dependent, truth-hostile and reality-denying person who is at the mercy of his own moods without self-control. A childish, dramatizing, hot-tempered and generally ridiculous creature, an egomaniac whose actions and demeanor are aimed solely at courting the applause of others. Or is Nietzsche not taking his word for it here? Should this really be his final verdict about the creative spirit?

He develops much of what Nietzsche describes about the artist on the figure Richard Wagner, with whom he has a brief, intensive, but ultimately disappointing acquaintance. The artist and the thinker could have been the ideal friendship for Nietzsche for a while. But after breaking with Wagner, Nietzsche has a lot of derogatory things to say about the artist as a type. How different — for comparison — is the friendship between artist and thinker in Narcissus and Goldmund by Hermann Hesse, who deals extensively with Nietzsche.

Determining Nietzsche

Determining Nietzsche

Does Nietzsche have clear philosophical doctrines? There is still a fight with Nietzsche's ambiguity today. When does he mean what he says? In her essay, Natalie Schulte explores the question of where, in the midst of assimilating ambiguity through ideological programs on the one hand and academically savvy dispersal of Nietzsche's thought structures into indiscriminate and incoherent fragments and perspectives, on the other hand, today's engagement with Nietzsche has to locate its decisive challenges. Between the dangers of confusing his philosophy and the limitless relativization of his theses, she is looking for a fruitful third way of dealing with the question of the “actual Nietzsche.”

Nietzsche and Music

Nietzsche and Music

For hardly any other philosopher, music was as important as it was for Nietzsche. “Without music, life would be a mistake”1, he wrote. Christian Saehrendt goes for Nietzsche PopArts The question of how this high appreciation of sound art was manifested in his life and work. He talks about Nietzsche's own compositions as well as one of the most iconic aspects of his life: his friendship with Richard Wagner. He shows that the music for Nietzsche is almost erotic It was important — and in this respect he was not so “out of date” at all, but a typical child of his time.

“Je suis Nietzsche!”

A Dialogue about Bataille, Freedom, the Economy of waste, Ecology and War

“Je suis Nietzsche!”

A Dialogue about Bataille, Freedom, the Economy of waste, Ecology and War

Paul Stephan talked to Jenny Kellner and Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann about the interpretation of one of the most important Nietzsche interpreters of the 20th century: Georges Bataille (1897—1962). The French writer, sociologist and philosopher defended the ambiguity of Nietzsche's philosophy against its National Socialist appropriation and thus became a central source of postmodernism. Based on Dionysian mythology, he wanted to develop a new concept of sovereignty that transcends the traditional understanding of responsible subjectivity, and criticized modern capitalist rationality in the name of an “economy of waste.” With all this, he provides important impulses for a better understanding of our present tense.

What Does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

What Does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

Our regular author Christian Saehrendt reports in his contribution to the series “What does Nietzsche mean to me? “about how he discovered Nietzsche as a teenager and has regarded himself as a fan of the philosopher ever since — precisely because of his contrariness.

The Desire for Waste

The Desire for Waste

What significance can a practice of waste have in today's advanced rationalization? Shouldn't we rather do everything we can to increase our efficiency and productivity if we want to meet the challenges of this crisis-ridden time? But when we turn to the thinking of Friedrich Nietzsche and his ardent admirer Georges Bataille, we are sometimes exposed to an emphasis of waste that shakes our moral principles and perhaps opens us up to a new and different kind of politics than the one that seems to impose itself on us today as having no alternative.

What does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

What does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

In the series “What does Nietzsche mean to me? “ over the next few weeks, our regular authors will each present their personal approach to Nietzsche and his thinking. Our senior editor Paul Stephan makes a start and reports on how he discovered Nietzsche as a teenager — and no longer necessarily sees himself as a “Nietzschean.”