Nietzsche and Music

Nietzsche and Music

For hardly any other philosopher, music was as important as it was for Nietzsche. “Without music, life would be a mistake”1, he wrote. Christian Saehrendt goes for Nietzsche PopArts The question of how this high appreciation of sound art was manifested in his life and work. He talks about Nietzsche's own compositions as well as one of the most iconic aspects of his life: his friendship with Richard Wagner. He shows that the music for Nietzsche is almost erotic It was important — and in this respect he was not so “out of date” at all, but a typical child of his time.

Torn between philology and art, between word and music, Nietzsche is also not immune from the religious exaltation of art typical of the time. He becomes a fan of Richard Wagner and temporarily tries himself as an amateur composer. For Nietzsche, the “unfinished composer” — a name attributed to Gustav Mahler — music was an essential theme of his life, but he chose the word as a vocation, as a weapon and as a tool.

In the Middle Ages and in some cases up to modern times, art and artists were at the service of religion. The church acted as a client; the artists and musicians had to decorate monasteries and cathedrals with paintings or to enrich the service with compositions. The artist was therefore an (anonymous) instrument of God. The better his works came to him, the greater was the love of God that was expressed in them. The view that all great art is praise of God has been held even into modern times, for example by the Catholic writer Marcel Proust. At a young age, Nietzsche also sees music primarily as a gift from God:

“Forever thanks be sung by God of us, who offers us this wonderful treat,” wrote Nietzsche in 1858 as just under fourteen years old:

God gave us music so that we firstly, are directed upwards through them. The music combines all qualities, it can uplift, it can dance, it can cheer us up, yes it is able to break the most raw mind with its soft, wistful tones. But its main purpose is that it guides our thoughts towards higher things, that it elevates us, even shakes us.2

_kleiner.jpeg)

The new art religion in the 19th century

In the Romantic period, the praise of God became a hymnal veneration of nature and art. In venerating historical and contemporary masterpieces, people now paid homage to a genius who lived in an inaccessible distance, although human. Art night and art enthusiasm were now an expression of a quasi-religious veneration of art. A well-known example of this was the collection of essays The heartfelt outpouring of an art-loving monastery brother by Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenröder and Ludwig Tieck. They told the life stories of “the great blessed art saints” in the style of hagiographies. At the beginning of the 19th century, also as a result of the French Revolution, the desire for originality and community spread. The reliance on emotional connection led to a new appreciation of feelings. Even in the final phase of the Ancien Régime, there was a countermovement to the rationality of the Enlightenment. Called “Sturm und Drang” in Germany, the Romantics opposed courtly authority and stiff formal traditions and instead focused on personal feeling and experience. Intimacy and enthusiastic goodness were now celebrated as the driving forces of private life and friendship. The love marriage became a bourgeois ideal, but friendly men also hugged and kissed each other intimately, wrote each other sentimental letters and swore eternal loyalty to each other. What would have been unthinkable in aristocratic court culture based on the French model became very popular in theatre, music and literature in the following decades. According to Nietzsche, the great popularity of the opera at the time was the layman's protest “against cold music that had been taught,” which was intended to regain a soul with the “revived polyhymnia”: “Without that profound religious change, without the abatement of the inner excited mind, the music would have remained taught. ”3 The cultivation of the emotional world, a now expressive, authentic language and a spiritually based veneration of art formed the basis of the new “art religion” of the 19th century. It transferred the spiritual-religious needs of the bourgeoisie to the arts, especially opera and symphony, primarily theatre and ballet, followed by poetry and the visual arts. Nietzsche recognized the scope of this historical trend: “Art rears its head where religions subside. She adopts a number of feelings and moods generated by religion, puts them close to her heart and is now becoming deeper, more soulful herself... “According to Nietzsche, religion is stronger than art, not the other way around, as some secular cultural people would like: “The wealth of religious sentiment that has grown into electricity breaks out again and again and wants to conquer new empires.” According to Nietzsche, In addition to politics and science, above all, art: “Wherever there is a higher level of human endeavor If you notice gloomy colors, you can assume that ghost gray, incense scent and church shadows have stuck to it. ”4

As part of the religious movement typical of the time that had swept over cultural life, opera and theatre became the ultimate artistic disciplines in a “Gesamtkunstwerk” -like, multi-sensual production. Renowned composers and virtuosos were revered as geniuses and treated as stars. Parallel to this enthusiastic mood in cultural and social life, however, hard-hitting capitalism changed the world. The natural sciences, in particular biology and medicine, experienced a strong upswing. The new art religion was used against the now rapidly advancing profanization, rationalization and scientification of all areas of society. One of their prophets was Richard Wagner. Wagnerianism soon polarizes the public as a new quasi-religious movement, and the young Nietzsche enthusiastically joins in. After a concert visit in autumn 1868 — the tristan-Prelude and the Meistersinger-Overture was on the agenda — Nietzsche switched entirely to the Wagnerian camp. Nietzsche gets to know Wagner personally in Leipzig, and he visits him at his house near Lucerne within the next three years 23 (!) Times — peak phase of that “star friendship” that Nietzsche started in The happy science alluded.5 Wagner also appreciates the admirer, who is 31 years younger. In 1872, he sums up: “Strictly speaking, after my wife, you are the only profit that life has brought me. ”6

Wagner may have exploited his young fan from the start and with long-term calculation. After Werner Ross, Wagner hires Nietzsche de facto as an academic PR powerhouse and ensures that he receives a professorship in Basel. Wagner needs an intellectual who certifies the high quality of his musical project. He uses his young wife Cosima to keep Nietzsche happy with many and long letters. Nietzsche praises in lectures and in his first publication The birth of tragedy from the spirit of music Wagner in heaven, sees him as a “reformer” and innovator of Dionysian Greek culture comparable to Luther. In a letter to Nietzsche, Wagner sees himself as an “prevented philologist,” while he describes Nietzsche as an “prevented musician.” Wagner dictates to Nietzsche the division of labor between the two: “Now remain a philologist in order to be conducted by music as such. ”7 Nietzsche fulfills the task by postulating that the Greek drama was created from original Dionysian music. Although this was destroyed by Socrates and Co., thanks to Wagner's genius, it is now possible to build on these original traditions after 2,000 years. The birth of tragedy, Nietzsche's first important work, contained a preface to Richard Wagner and was explicitly dedicated to him. At the time, Nietzsche presented him as a possible new founder of a culture comparable to Greek and, as an avowed Wagnerian, at the same time distanced himself from scientific philology. As a result, his further scientific career was blocked — as a philologist, Nietzsche was ruined from then on. The friendship, which was fragile and charged with expectations from the outset, lasted ten years and finally turned into harsh criticism:

We were friends and became strangers to each other. [...] That we must become strangers is the law about us: by doing so, we should also become more venerable! It should also make the thought of our former friendship holier! [...] And so we want to believe in our star friendship, even if we must be enemies of each other on Earth.8

Musical achievements and music criticism

In the 19th century, art entered unimagined spheres that were previously reserved for the sacred. At the same time, however, modern music criticism is also developing. Back then, music may have reached the height of its historical appreciation — both in sensory experience and as an object of analytical thought. Nietzsche's thinking about music should also be considered against this background. Throughout his life, but without systematics, he has been involved in music theory discussions. He is also increasingly critical of Wagner's work — and dedicates a brilliant polemic to him: “My biggest experience was a recovery. Wagner is just one of my illnesses. ”9 On a practical level, Nietzsche worked as a veritably talented pianist from childhood, and he also started attempts as an autodidactic composer. In addition to more conventional song compositions from his youth, his later Manfred meditations relevant, which were created under the influence of Wagner music and were probably also intended for performance before Wagner. However, Nietzsche made the mistake of asking Hans von Bülow, the composer and Wagner conductor, for a professional opinion. This is indiscriminate: “An imagination tumbling in remembrance of Wagnerian sounds is not a production basis. ”10 In fact, Nietzsche's compositions show little innovation that could point to music of the future. As a musician, Nietzsche remains more conventional. It is not surprising, the NZZ once summed up,

that Nietzsche, who boasted in letters that there had never been a philosopher who was a musician to the extent and to the extent that he was himself, had barely any effect due to his musical convictions. Today, over a hundred years after his death, the philosopher Nietzsche is a European figure of undeniable significance, and the “unfinished composer” Nietzsche is a historical episode.11

What did music really mean to him?

Nietzsche made numerous commitments to music — especially in his youth, but also in the last conscious years of his life. But how intensely Nietzsche really perceived the music remains an open question in the end. What did he particularly appreciate about music?

Was it pure sound enjoyment, a purely formal, concrete musical experience, so to speak? Or wasn't the religious charge of listening to music more likely to create feelings of grandeur? So was the combination of listening to music with educational background, with lyrics (poetry) and with a historical-religious context decisive for enjoyment? “Music is not in and of itself so meaningful for our inner self,” writes Nietzsche, but only poetry has “placed so much symbolism in rhythmic movement, in strength and weakness of sound, that we think it speaks directly to the interior and comes from within.” It was therefore only the intellect that “put meaning into the sound.” ”12 Some current authors speculate that music has enabled him to reach and express deeper layers of unconscious feeling.13 But this positive attitude in his youth is soon overshadowed by suffering from the contrast between science and art. Nietzsche sees the need to “escape from rapid changes in artistic tendencies into a haven of objectivity,” as he writes in an autobiographical review from around 1868.14 Nietzsche notes elsewhere: “[N] he lives with some peace, security and consequence only by forgetting himself as a subject, and indeed as an artistically creating subject.”15 He attempts this agonizing contrast through his theses in his first work The birth of tragedy to overcome. “As a musician, Nietzsche is certainly a romantic in general,” Curt Paul describes Janz Nietzsche's dilemma, but after “as a thinker he begins to overcome Romanticism, Schopenhauer's romantic musical criticism, he must fall silent as a musician and alienate himself from Wagner. ”16

Little is known of Nietzsche's sex life and sexual orientation. It is entirely conceivable that the excitement of music also had an erotic component in him. Once, Nietzsche notes down a “ranking” that appeals to him the most. First place: “musical improvisation in a good hour”, then: listening to certain pieces by Beethoven and Wagner, third: thinking while walking in the morning, the fourth is “Vollust”, which ends the list. “When he fears the lust of sexual intercourse — not that of desire — and flees, he experiences his music and the inventive wandering of his mind voluptuously, with sensual intensity,” concludes Werner Ross in his book The Wild Nietzsche, or the Return of Dionysus.17

There are apparently three sources of energy that recharge and intensify Nietzsche's love for music: religion, poetry and Eros. According to Nietzsche, music and the other arts needed a particular “physiological precondition,” the intoxication, especially the “frenzy of the festival.”18. According to Nietzsche, creativity can only develop uninhibited from a state of excitement in which clear thinking and rational consciousness have been switched off or dampened. Thinking further: The works of art created in intoxication are particularly good and successful works of art when they in turn can make viewers and listeners feel intoxicated. Nietzsche is obviously very enthusiastic about intoxication and its numerous variants. He raves about the “intoxication of sex,” but also about the “intoxication of celebration, competition, bravura, victory, all extreme movement; the intoxication of cruelty; the intoxication of destruction.” The motive for the conspicuous praise of all sorts of Dionysian debauchery may be found in his education, but above all in the lack of “debauchery” actually experienced. Here, the music experience certainly also offered an opportunity for sublimation. And so the realm of music served him as an overflow basin for the powerful floods of instincts and feelings.

Literature

O.A.: Life without music is simply a mistake. Online: https://www.nzz.ch/articleDLWL3-ld.38202.

Figl, Johan: Feast day cult and music in the life of young Nietzsche. In: Günther Pöltner e. a. (ed.): Nietzsche and music. Frankfurt am Main 1997, pp. 7—16.

Janz, Curt Paul: Nietzsche's Manfred Meditations. In: Günther Pöltner and others (ed..): Nietzsche and music. Frankfurt am Main 1997, pp. 45—79.

Nietzsche, Friedrich: [From the years 1868/69]. In: Works in three volumes. Munich 1954, pp. 148—154.

Ders. : About music, in: From my life (1858). Online: http://www.thenietzschechannel.com/works-unpub/youth/1858-fmlg.htm.

Ross, Werner: The Wild Nietzsche, or the Return of Dionysus. Stuttgart 1994.

Footnotes

1: Götzen-Dämmerung, Sayings and arrows, Aph 33.

2: About music.

3: Human, all-too-human I, Aph 219.

4: Human, all-too-human I, aph. 150.

5: Cf. The happy science, Aph 279.

6: Cit n. https://www.wagner200.com/biografie/biografie-1866-1870-exil.html.

7: Quoted by Werner Ross, The wild Nietzsche, P. 59.

8: The Happy Science, Aph 279.

10: Quoted by Curt Paul Janz, Nietzsche's Manfred Meditations, P. 52.

11: OP., Life without music is simply a mistake.

12: Human, all-too-human I, Aph 215.

13: See, for example, Johan Figl, Feast day cult and music in the life of young Nietzsche, P. 12.

14: [From 1868/69], p. 148.

15: About truth and lies in an extra-moral sense, paragraph 1.

16: Janz, Nietzsche's Manfred Meditations, P. 47.

17: P. 114.

18: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, Aph 18.

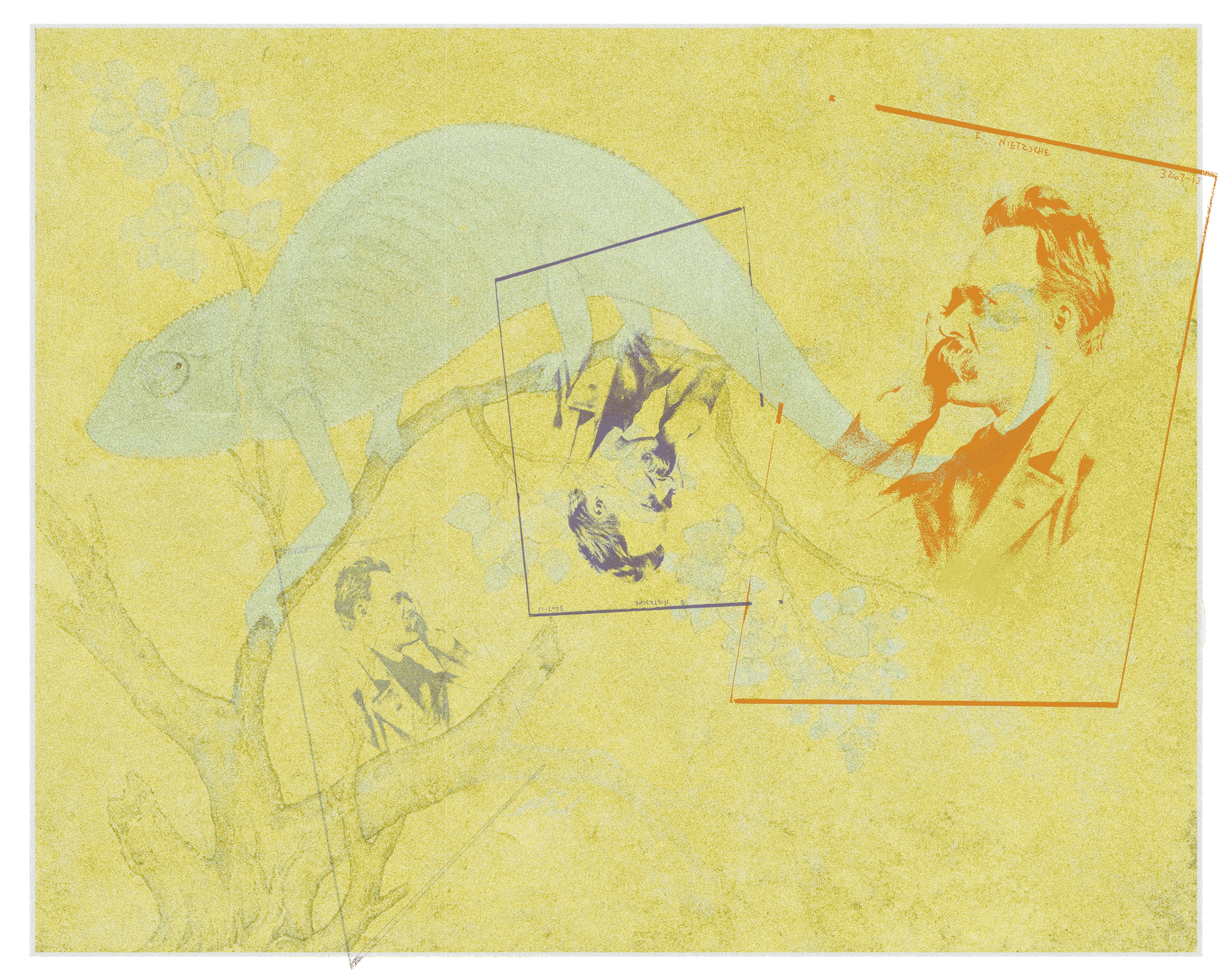

Source of the Article Image

Jens Fläming, A Nie-Na-Nietzschemann is dancing. Oil on canvas, 1984. Nietzsche Documentation Center Collection in Naumburg. (Image courtesy of the artist.)