Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Individualism, even egoism, is frowned upon in all political, religious and social camps. They are attributed to liberalism and capitalism. Such people are not committed to others, are not involved politically or for the environment. They also do not respect a common understanding of the world and therefore behave irresponsibly. The Nietzschean is not impressed by such verdicts. She dances — not only!

“The whole world revolves around me/Because I am only an egoist/The person who is closest to me/Am I, I am an egoist,” Falco sings in 1998.

“Love your neighbor as yourself! ”

What does Nietzsche say about this in 1888? “You live for today, you live very quickly — you live very irresponsibly: this is called 'freedom' right now . ”1 Being irresponsible and being able to do what you feel like doing right now, not getting married and certainly not having children, not making any commitments, that is La dolce vita.

Selfishness is not the same as individualism. Historically, egoism precedes individualism. The Old Testament contains the famous commandment “You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), which does not reject self-love, in fact bases charity on self-love.

When Christianity strengthens this commandment, namely “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44), there is not much left of self-love. There is nothing more to be seen of self-confident egoism when the Church Fathers around 400 demand absolute obedience from believers and the confession of all sinful thoughts, not just actions: The end of egoism!

From individualist Leonardo to capitalist egoism

Individualism only emerged in the Renaissance: The aim of people is their all-round education and the development of their abilities. This personifies Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), an illegitimate child from a middle class, not noble background. The self is now given its own touch, as a result of which the person begins to free himself from the constraints of faith. Leonardo was an atheist and homosexual. “What people call love is in reality nature's always the same smear comedy”2, according to Volker Reinhard, Leonardo assumes. With this individualism, ancient egoism is rehabilitated in a moderate form.

Selfish individualism reaches its climax when John Locke (1632-1704) attests inalienable natural rights to humans as individuals. The most important of these is the right to own property. The primary purpose of the state is to protect this. In Calvinism, wealth is even regarded as a sign of divine mercy. Bernard de Mandeville (1670-1733) writes in plain language when he describes economic egoism as a private vice, but it leads to public benefit, i.e. promotes the general good.

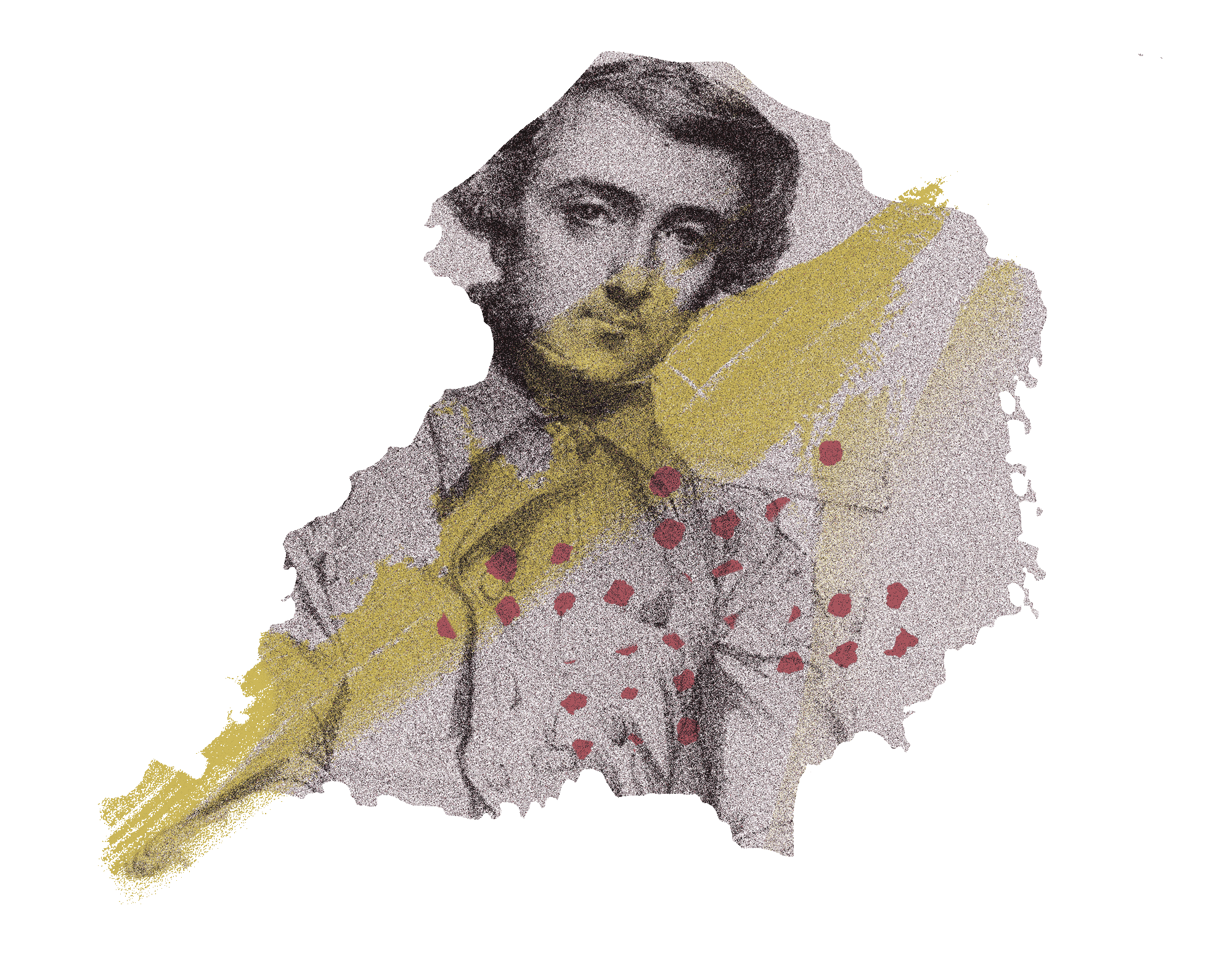

Religiously conservative criticism of individualists: Tocqueville

This lays the foundation for severe criticism of individualism when liberalism elevates capitalism to the political economy of the bourgeoisie. The harshest critics of liberal individualism initially came from the religious-monarchical camp. One of the main representatives is the French politician and political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859).

This is how he writes in 1835 in About democracy in America: “The poor” — compared to the nobility, this includes the citizens — “has retained most of the prejudices of his ancestors, but without their faith, their ignorance without their virtue; he has made the doctrine of private interest the guideline of his actions without knowing its scientific basis, and his egoism is as free of education as his devotion once was.” (p. 30) Such individualism when people their Faith as they have given up their morals pursues material benefits alone without regard for others and So without regard to the state.

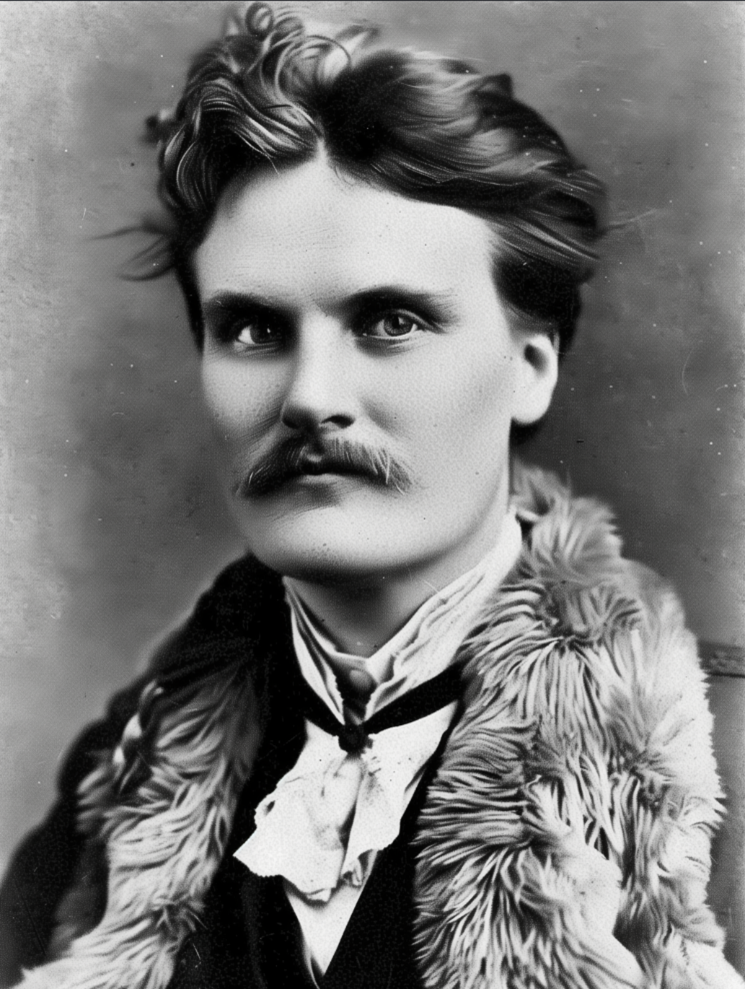

Nietzsche: “Who still wants to obey? ”

Did Nietzsche, who was only two generations younger, write off almost 50 years later? In his corpus, Tocqueville appears twice, and praises it.3 Denn So Zarathustra spoke: “Who still wants to govern? Who else obeys? Both are too cumbersome. Not a shepherd and a host! Everyone wants the same thing, everyone is the same”4. Even for Nietzsche, most citizens only care about their private interests and do not like it at all when the state and society get involved in this.

The bourgeoisie does not want to govern in this way; they prefer to leave it to the nobility. At the end of the 19th century, liberals such as the hard-working Nietzsche reader Max Weber (1864-1920) doubted that the bourgeoisie was even capable of doing so; until the French Revolution, the nobility ruled almost everywhere. Because the bourgeoisie is only interested in the economy and individual advantage, they have no view of the whole thing. How can it then take care of the community and the common good? The king, on the other hand — according to Tocqueville — had taken care of exactly that.

Such a lawsuit can also be found today and in almost all political camps: Liberalism is extremely unpopular, individualism all the more so and it is accused of egoism. Both are held jointly responsible for the fact that people no longer engage in politics and instead withdraw into private life, that they no longer serve the state or society, but only want to take advantage of it — even refuse military service.

Nietzsche shares Tocqueville's critique of individualism, but not his orientation towards the common good, which Nietzsche questions, while Tocqueville focuses on it. For Nietzsche, the common good is a bourgeois illusion. What does it say in the 1887/88 estate: “'The good of the general requires the dedication of the individual. '. But lo and behold, it Gives No such general thing! ”5

Decline of values and the “last person”

Tocqueville, on the other hand, not only notices that there is, of course, a common good, but that it is precisely democracy that particularly requires people's commitment to the common good, as he had observed on his journey through the USA in 1831. Because democracy in particular includes various commonalities among citizens — women had no civil rights at all — which he misses in France. He writes:

It seems as though the natural bond that connects opinions with tendencies, action with thought has been broken; the harmony that can be felt at all times between man's feelings and ideas seems to have been destroyed, and one is almost inclined to say that all laws of moral responsibility have been abolished.6

To this day, religious, conservative and right-wing circles complain about the disintegration of common moral values and demand a “spiritual and moral change.” Tocqueville was one of the first to provide the arguments for this. Disbelieving himself, he nonetheless criticizes the widespread disbelief, as for him the common religious faith has a stabilizing effect on every state. But when people are no longer religious, they are no longer bound by such a bond.

A similar lawsuit, which of course drifts in a different direction, is also found in Nietzsche when he describes the mass of his contemporaries as “last people” because they only pursue materialistic interests. Nietzsche writes: “Look! I'll show you The last man. “What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is star? '— this is how the last person asks and blinks. The earth has then become small, and the last person who makes everything small jumps on it.”7, and pays homage to mass individualism.

But while Tocqueville conjures up the return of religious values, Nietzsche wants to leave them behind, but demands new ethical values that need to be invented. For Nietzsche, this is not just the task of the superman, but of those who should follow his doctrine and proclaim it. This is where the paths of Tocqueville and Nietzsche separate. Because Tocqueville actually believes that traditional values are correct, while new values that people invent themselves are an expression of individualism.

But there are other similarities between Tocqueville and Nietzsche. Because even this one certainly does not simply leave all traditions behind. Tocqueville blames individualism for breaking up family ties, because even within families, money is all that matters and the willingness to make sacrifices for the family decreases.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, broadened his criticism from the outset. Where Tocqueville primarily individualism, not liberalism per se, since he shares certain basic liberal assumptions, Nietzsche criticizes liberalism itself, which includes the individualism of the “last people,” but not that of the heralds of the superman, who are not affected by what he writes in the following quote:

For institutions to exist, there must be a kind of will, instinct, imperative, anti-liberal to the point of malice: the will for traditions, for authority, for responsibility for centuries, for the solidarity of gender chains forwards and backwards in infinity.8

Of course, that is no longer the case. Nietzsche also laments the decline of the institution of the family as a result of bourgeois individualism, similar to Tocqueville. On the other hand, he is also a critic of the family. How does Zarathustra say: “This is what a woman said to me: “I broke up, but broke up first — me! '”9

Freedom of speech as a weakening of the state

For Tocqueville, individualism also leads people to imagine that they can make judgments about everything and everyone themselves. However, this promotes mutual distrust. Authorities are no longer recognized by the public. For Sarah Strömel, Tocqueville is already anticipating the state of democracies today. She writes:

This profound mistrust in the findings of others, no matter how established or proven experts, and also the general lack of trust in others, jeopardize cohesion in democracy. The excessive hubris that goes with it also makes individuals blind to their own ignorance.10

As early as 1872, Nietzsche criticized educational institutions in a similar way that they would educate people to have their own opinion and thus contribute to overconfidence, as Strömel complains. He writes:

Here, everyone is readily regarded as a literate being who has their own opinions about the most serious things and people should, while a right education will only strive with all zeal to suppress the ridiculous claim to independence of judgment and to accustom the young person to strict obedience under the scepter of genius.11

Education should help people recognize authorities, Nietzsche's brilliant people, and their opinion leaders and adopt their views without questioning them. Nietzsche thus radicalizes Tocqueville's assessment when in 1886 he spoke about “the introduction of parliamentary nonsense, including the obligation for everyone to read their newspaper for breakfast.”12, laments.

When it comes to democracy, Tocqueville is divided, as he is leaning towards monarchism. Unlike Nietzsche, however, he recognizes the democracy that has spread in the contemporary state. For Tocqueville, a common view of the world is absolutely essential for democracy. In the absolutist monarchy before the French Revolution, Catholicism did this. Nietzsche doesn't see things completely differently. He wrote in 1888:

There is no other alternative for gods: either Are they the will to power — and for as long as they will be gods of the people — or But powerlessness — and that's when they become necessary well.13

As a result, religion loses its guiding power and is no longer able to generally enforce faith and supreme ethical values. Søren Kierkegaard criticizes the churches in 1850 for proclaiming a dear God who can only be a punishing god. Nietzsche has a similar view, while Tocqueville complains of a loss of faith, but not yet, in the sense of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, the transformation of the punishing God into a merciful one.

From monarchy to democracy

Tocqueville notes that the general situation in the Ancien Régime was constantly improving. But dissatisfaction grew all the more. “Reform frustrates and makes rebellious,” writes Karlfriedrich Herb and he adds that Tocqueville notes “how reducing social inequality increases discomfort about remaining inequality. ”14 According to Herb, the “Ancien Régime” for Tocqueville is “a revolution before the revolution. ”15 In fact, the monarchy understood governance better; in particular, it was friendlier towards its subjects than democracy.

Because in the monarchy, the king's power was significantly more limited than in democracy, through tradition, the co-governing nobility and through the institutions. Tocqueville states: “No monarch is so unlimited that he could combine all forces of society in his hands and overcome all opposition in the same way that a majority can with the right of legislation and law enforcement. ”16 In democratic states, there are indeed various forms of separation of powers between legislative, executive and judicial branches. However, the division of powers has only prevailed with regard to the judiciary and only partially. In the USA, Hungary and Poland, attempts are even being made to undermine the autonomy of the judiciary.

In his later writing L'Ancien Regime et la Revolution Dating from 1856, Tocqueville values democratic institutions while distrusting citizens. After Herb, Tocqueville also doubts that democracy will prevail. Herb writes: “A liberal end to the story thinks Tocqueville is illusory. ”17 For this reason, Francis Fukuyama's dream in 1989 that the world will become democratic after the end of the Soviet Union cannot come true; because, according to Fukuyama: “The liberal state is necessarily universal.”18th In fact, it doesn't look like it anymore at the moment. Democratic systems are more likely to be under pressure today. That would probably be no problem for Nietzsche. Tocqueville, on the other hand, predicts such a development, which he would have regretted.

From democracy to dictatorship

Tocqueville sees the centralization of states as a threat to both monarchy and democracy. He writes: “For my part, I cannot imagine that a nation can live or prosper without strong government centralization. But I believe that a centralized administration is of no use but to weaken the peoples subject to it, because it unceasingly reduces the spirit of citizenship in them.”19 and thus intensifies the retreat into private life.

Without centralization and bureaucratization, no state can be created. But both restrict the scope of monarchy and democracy. This disappoints citizens, who are no longer politically involved. This is how they experience themselves as isolated individuals. You could think of today's People's Republic of China.

For Tocqueville, on the other hand, everyone in the monarchy is unequal, but is integrated into a network that gives them support and meaning. For Nietzsche, there is a similar but even more radical rejection of equality. He wrote in 1888:

The doctrine of equality! .. But there is no more poisonous poison: because they seems preached by righteousness itself while they termination who is justice. “The same, the unequal, the unequal — That The true message would be justice: and, as a result, never make unequal things the same. ”20

For Nietzsche, too, equality individualizes people with the result that they no longer recognize authorities. It's just that Nietzsche doesn't regret the damage that democracy is doing in the process. Rather, this opens up the opportunity to find his way back to a monarchy, which he certainly wants to be led by a brilliant king, whom he cannot recognize in Wilhelm II towards the end of his waking life in 1888.

Nietzsche's dancers as individualistic elite

But there is still a clear difference with Tocqueville. Nietzsche is no simple opponent of individualism and egoism like Tocqueville. Nietzsche sees this in a more differentiated way. Yes, he even praises the egoism, which he individualistically expands, which can be found today primarily in the media world. So Zarathustra spoke:

And it happened back then too — and truly, it happened for the first time! — that his word is selfishness Blessed praise, the healthy selfishness that springs from a powerful soul: — from a powerful soul, to which the higher body belongs, the beautiful, victorious, refreshing thing around which becomes a mirror: the supple persuasive body, the dancer whose likeness and excerpt is the self-loving soul. Such body and soul self-lust is called itself: “Virtue. ”21

Ergo: Let's Dance (RTL)? But Nietzsche doesn't mean women. It is not yet the time of Marilyn Monroe or Claudia Schiffer — two of the many super beauties among movie and model stars. But whether in Nietzsche's “the beautiful body of the dancer” or the extensive sexiness in the RTL dance show, both require that you apply makeup and style your body, although for Nietzsche, this is more due to liveliness.

Nevertheless, for conservative Tocqueville, this would probably be outside of what he acknowledges — as the Conservatives called for a spiritual and moral change in the 1980s. But Tocqueville could not yet have foreseen that. Nietzsche, on the other hand, is more open to this.

Beauty presents the individual as something special who is not only different from others, but also stands out. This is where individualism and egoism or selfishness meet. Striving for one's own beauty realizes egoism in individualism. This is how Jean Baudrillard writes:

The Church Fathers understood this well, as they scourged it as something that belongs to the devil: “Taking care of one's body, caring for it, putting on makeup means posing oneself as God's rival and contesting creation. ”22

Nietzsche would have no problem with that. But he would attribute the media noise of a Friday night dance show to the ambiance of the “last people.” But Nietzsche is not only concerned with the beautiful soul, but also with the beautiful bodies, which today owe less to nature than to techniques. With their individualism and egoism, the heralds of his teaching, who today of course include female proclaimers, belong to a small elite beyond the media market.

Afterword: individualism that is unpopular everywhere

Tocqueville, on the other hand, would attribute Nietzsche's entourage to apolitical individualism, which poses a threat to democracy. But he would have many advocates. Warring states in particular emphasize community-oriented values, truly not just Russia with its large family. Nazi-ruled Germany awarded the mother cross in bronze for four or five children for their Aryan and morally sound mother. In accordance with its policy program, the Alternative for Germany wants to increase the birth rate through financial incentives. Tocqueville thus finds himself in an unpleasant neighborhood, from which Nietzsche frees himself through his followers and thus also from a past reading of his works as a Nazi philosopher.

sources

Baudrillard, Jean: Of seduction (1979). Munich 1992.

Fukuyama, Francis: The end of the story — Where are we? Munich 1992.

Herb, Charles Frederick: Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old State and the Revolution (1856); in: Manfred Brocker (ed.): History of political thought. The 19th century. Berlin 2021.

Reinhardt, Volker: Leonardo da Vinci — The Eye of the World — A Biography. Munich 2018.

Strömel, Sarah Rebecca: Tocqueville and individualism in democracy. Wiesbaden 2023.

Tocqueville. Alexis from: The old state and the revolution (1856). Munich 1989.

Ders. : About democracy in America (1835/40). Stuttgart 2021.

footnotes

1: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, 39.

2: Leonardo da Vinci, P. 272.

3: Cf. those position in the estate and those Letter to Overbeck.

4: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 5.

5: Subsequent fragments 1887/88, no 11 [99].

6: About democracy in America, P. 31.

7: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 5.

8: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, 39.

9: So Zarathustra spoke, From old and new boards, 24.

10: Tocqueville and individualism in democracy, P. 97.

11: About the future of our educational institutions, presentation 2.

12: Beyond good and evil, Aph 208.

13: The Antichrist, paragraph 16.

14: Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old State and the Revolution, P. 455.

15: Ibid., p. 450.

16: About democracy in America, P. 180.

17: Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old State and the Revolution, P. 446.

18: The end of the story — Where are we?, P. 280.

19: About democracy in America, P. 76.

20: Idol twilight, rambles, 48.

21: So Zarathustra spoke, Of the three bad guys, 2.

22: Of seduction, P. 128.