What Does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

What Does Nietzsche Mean to Me?

Our regular author Christian Saehrendt reports in his contribution to the series “What does Nietzsche mean to me? “about how he discovered Nietzsche as a teenager and has regarded himself as a fan of the philosopher ever since — precisely because of his contrariness.

I became a Nietzsche fan at the age of sixteen or seventeen — that is the age at which you absolutely want to be a fan of something or someone, a fan in the sense of superficial admiration and a demonstrative will to confess. Back then, I only had a vague idea of Nietzsche as a gloomy, dazzling and, all in all, somewhat eerie figure. In this regard, Nietzsche suited my passion for haunted and scary characters, horror, musical hardcore and various “Monsters of Rock.” Dealing more closely and systematically with Nietzsche's work — back then I lacked the intellectual discipline and ultimately the will: because as a young fan, you might not even want to get too close to your idols. Perhaps you would rather see them at an unreachable distance or cultivate nebulous projections of your own juvenile ideas of grandeur? And it was also important for Nietzsche to keep a certain distance from the fans: “You have to know how to darken yourself in order to get rid of the swarms of mosquitoes from overly annoying admirers.”1, he wrote down about it.

That Book from the storage room

Well, I didn't have Friedrich Nietzsche star cut posters in my pitched youth room, but I would still have described myself as a Nietzsche fan. His often loud-mouthed and presumptuous aphorisms impressed me as a “half-strong”; his philosophy seemed perfect for anyone who doubts authority — parents, teachers, priests. Young people must do this in order to be able to mature into an independent personality at all; contradiction and doubt are good and necessary in principle. However, there is a downside to rebellion and dissociation: self-doubt, loneliness, sadness. You long for soul mates, they are not always at hand, so imagination comes into play. In the preface to Human, all-too-human Nietzsche wrote:

So once, when I needed it, I also had the free spirits invented[.] [...] [D] equate free spirits do not exist, did not exist — but back then I needed them to society in order to remain good things in the midst of bad things (illness, loneliness, strangers, Acedia, inaction): as brave journeymen and ghosts with whom you talk and laugh [.]2

This is a genuine artistic concept that sounds familiar to me from my own experience, albeit in a mild version, from my youth: The escape into an art world, which, however, is on the verge of delusional world if you go too deep into it. You invent characters, equal friends, dream of a community of like-minded people. In this way, isolation and powerlessness can be endured, but not permanently, but only as a phase of latency until the real outbreak takes place, until the search for real spiritual relatives and comrades begins. It is a well-known phenomenon in the late phase of adolescence: Now self-esteem develops, but sometimes oversteps the mark. As a result, overconfidence is felt right up to the point of delusions of grandeur. A phenomenon that has obviously proved its worth in terms of evolution, because it produces courage and, under certain circumstances, inspiring enthusiasm. You feel incredibly strong, beautiful, irresistible, witty and visionary in this state — ideally the natural state of all artists. On the one hand, young people and artists are therefore linked by intoxicating overconfidence at the moment when they feel themselves, when they discover their self-effectiveness, be it physically, mentally, creatively. On the other hand, both also know the feeling of misunderstanding, of being misunderstood. Nietzsche summed up this ambivalence:

The artistic genius wants to make you happy, but when he is at a very high level, he easily lacks the people who enjoy it; he offers food but you don't want it, his pipe sounds, but no one wants to dance. Can that be tragic? Perhaps it is.3

If Nietzsche were still alive and would go on reading trips with stops at various Thalia or Orell-Füssli branches, I would hurry over and present him with a specific book asking for an autograph. It is a paperback edition of Human, all-too-human out of the series Goldmann's Yellow Paperbacks, published in Munich in 1960. I discovered it in 1985 on a remote shelf in my parents' house, in a book cemetery, where what had been read or never read was collected. My parents bought it at the beginning of the 1960s during the prime economic miracle period, when intellectual hunger became noticeable as the legendary feeding wave subsided, or became a status symbol as education and bookshelf. My parents never talked about philosophy; Nietzsche wasn't a topic of conversation with us. The book must therefore have arrived in our household out of educational commitment or as a gift. I took it off the shelf, it looked unread, even though the cheap paper was already brownish. I read it and kept it to this day. It is not a beautiful book, a haptic or visual experience. I would present Nietzsche with a visibly inexpensive book for signature today, the cover is somewhat rubbed and dusted, a strangely colorful psychedelic cover motif would light up at him, individual pages are cracked and come off the adhesive binding, bent side corners, so-called dog-ears, threaten to break off. The spine of the book is missing and has been replaced by brown package tape. In the book, there are numerous passages marked by my hand, pencil and ballpoint pen were used hastily to underline, wild paintings of neon highlighters, fading in passages back to rosé, mint green and Naples yellow, traces of an unsystematic, discontinuous and erratic, yet at the same time disturbing reading!

It was Nietzsche's fault that I wanted to be an artist.

Nietzsche was and is regarded as an advocate of art and a Dionysian artistic lifestyle — even though he himself probably dreamt of it rather than practising it. He wasn't known as a party animal. Apart from extroverted fame and intrinsic creativity, it was also the artistic lifestyle itself that attracted people to art. Bohemians and free spirits, artist colonies and the life reform movement have stood for an alternative way of life since the beginning of modernity. “Become an artist” promised an escape from stuffy confinement, provincial stink, military drill and bureaucratic routine. Nietzsche became popular back then as a pillar saint for artists and all who would like to be. For over 150 years, his writings have inspired people for art — and many from the middle class and the petty bourgeoisie in particular felt appealed to many. I was one of them too. Nietzsche was one of the sources of inspiration that led me to want to turn my hobby into a career, to study at an art academy in Hamburg in faith in my “genius” and later to live as a visual artist in Berlin for a few years. Once I also picked up the brush to paint the philosopher myself — lying in a bed that his sister would have screwed together for him.

Today, it seems to me that I was a latecomer in my Nietzsche enthusiasm. We realized that today's artists rarely deal with Nietzsche. In my opinion, there are several reasons for this. First, the changed self-image of this profession: The transfiguration of Nietzsche as an apostle of heroic and megalomaniac artistry is a thing of the past. At that time, his writings offered the ideal legitimacy for the new self-image of avant-garde artists who did not want to tolerate any more traditional authority over themselves. On the one hand, Nietzsche was regarded as the key witness of the liberated, creative individual, and on the other hand as the catchword for an elitist (and potentially) totalitarian world betterment: The artist as the advancing herald of the future, the artist as a demiurge. In that “age of extremes,” aesthetic modernism was constantly in the tension between totalitarianism and democracy; it fluctuated between an aristocracy of spirit and collectivist visions of society. Today's artists, on the other hand, avoid pathos and fantasies of omnipotence so as not to appear too narcissistic. At that time, Nietzsche impressed many artists with his critique of science and rationality. To an ossified and misanthropic rationality, he set art as the last “stimulant of life” still effective in present-day nihilism4 opposite. In principle, this may be flattering and acceptable to every artist, but it still seems outdated today, as many artists are currently seeking to join forces with science: Instead of Dionysian intoxication, it urges them to engage in boring “artistic research,” bureaucratic third-party funding and applying for project funding. Contemporary artists are now regarded as so-called interface actors who mediate between art and science, aesthetics, technology and consumption, largely obeying regulatory and scientific authorities in order to “save the climate” or produce “queer” and “post-colonial” statements. Today's artists must always think of sponsors, customers and competitors, of new markets and fashions. They are often masters at identifying new consumption patterns and social trends. Nietzsche would not be able to win a majority among current juries, funding institutions and sponsors — which is why art avoids him.

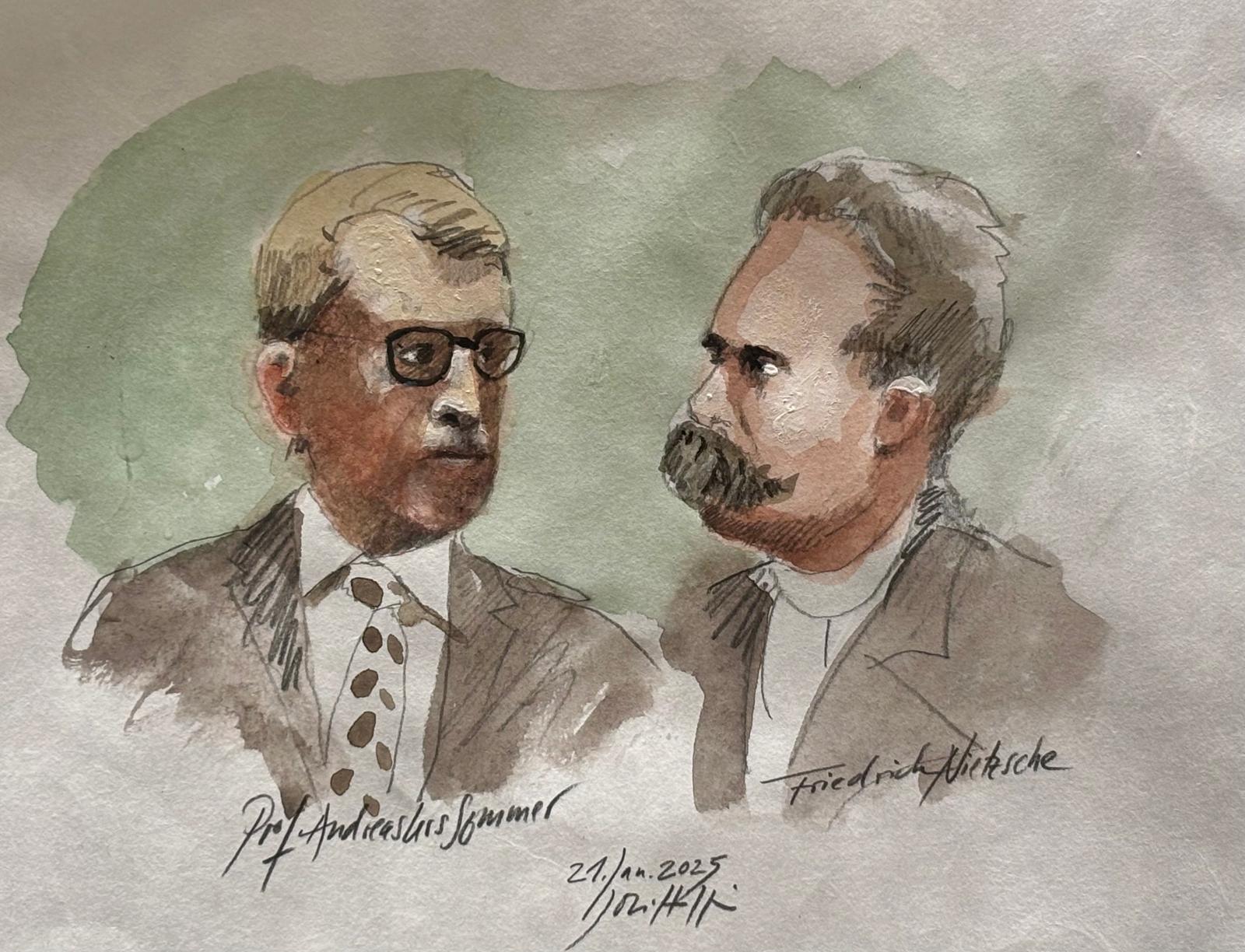

One important reason for this is that Nietzsche is not part of the canon of left-wing thinkers. Paul Stephan has pointed out that Nietzsche is almost impossible for leftists to adopt because he was convinced of the inequality of humanity and actually assumed that social inequality was a social necessity.5 Instead, Nietzsche in Central Europe is still under general suspicion of being the godfather of far-right ideas. Defining him as a “house philosopher” of the New Right or the AfD may, however, be regarded more as a journalistic prejudice.6 According to Andreas Urs Sommer, however, Nietzsche can certainly be described “as a politically incorrect thinker”: “He takes very fundamental political self-evident principles, such as the idea of equality that we have of people, he questions the values of the French Revolution and also of the Enlightenment that precedes this revolution. ”7

In a weird fan club. So what?

In order to understand this ambivalent relationship between today's society and Nietzsche, let's look at which VIPs are publicly committed to Nietzsche. For example, who visits his grave in the Röcken Memorial near Leipzig, and which prominent cultural figures and politicians can be seen here? There are only a few. In the 1990s, the then Minister-President of Saxony-Anhalt, Reinhard Höppner (a Protestant and ecclesiastically engaged SPD politician), Joseph Fischer (THE GREENS, then foreign minister on an election campaign tour) and Wolfgang Wagner (grandson of Richard Wagner and then director of the Bayreuth Festival). Only a few other celebrities identify themselves as Nietzsche readers; former President of the Protection of the Constitution Hans-Georg Maaßen was an exception here. While on duty, he had a copy of Edvard Munch's Nietzsche portrait hung in the study and, looking back, was disappointed that many visitors, especially politicians, had not recognized the philosopher.8 Widely avoided in Central Europe and particularly in the left-liberal milieus of the cultural sector, Nietzsche, on the other hand, is receiving more attention in Asia and America, for example in China, where a first wave of Nietzsche reception was already observed during the reform phase of 1978,9 And in South America, in recent years, people could almost speak of a Nietzsche boom. In 2014, the recipient of the “Leipzig Book Prize for European Understanding”, Pankaj Mishra, contacted the memorial in Röcken at his own request. Mishra, who flirts with anti-democratic resentment in his books and rejoices about the imminent “decline of the West,” asked himself to remain alone at the grave for ten minutes. In 2016, there was a strange appearance by the then Prime Minister of Saxony-Anhalt, Rainer Haseloff (CDU), who let himself be seen at Nietzsche's grave on an election campaign tour — accompanied by tableau-Newspaper. In 2018, the Russian oligarch Vitaly Malkin made a pilgrimage to Röcken to confess Nietzsche and his book Dangerous illusions to advertise. The German press speculated about his motivation: “Is Malkin's book a megalomaniac method of setting yourself a memorial? In addition to yacht, luxury apartment, family foundation? And: Why exactly does this rich Russian love Nietzsche so much? ”10 Nietzsche is therefore still surrounded by an aura of the uncanny. The fact that it is often somewhat strange people who openly profess Nietzsche contributes to this. In the Nietzsche fan club, you sometimes meet strange company, even though you can hardly blame the philosopher for this. Nietzsche was occasionally called upon as a godfather by nihilistic perpetrators of violence, such as the high school assassins at Columbine: “I simply love Hobbes and Nietzsche”11. Or by Norwegian mass murderer Anders Breivik. In his manifesto 2083 — A European Declaration of Independence He mentions Nietzsche in ten places.12 The accumulation of Nietzsche quotes and references in Norway's violent black metal scene also fits into this pattern.13 In this context, it is not very reassuring that former American boxing legend Mike Tyson has also been committed to Nietzsche for several years: “Most philosophers are so politically incorrect — challenging the status quo, even challenging God. Nietzsche's my favorite. He's just insane. You have to have an IQ of at least 300 to truly understand him. ”14 Admittedly, as a Nietzsche fan, I'm in strange company. And yet I can say from the bottom of my heart: I had the right instinct back then. To date, I feel fully confirmed in my life as a fan. The more I learned about Nietzsche's work, life and reception, the clearer it became to me that he is still THE godfather of all intellectual outsiders. His equally sharp criticism of science and religion, his relentless struggle against resentful philistines, bigots and duckmice, his insight into the inevitability of loneliness and sadness, his heroic-tragic pathos — all of this is difficult to communicate in today's society. And yet it is highly topical. The fact that Nietzsche receives occasional applause from the wrong side doesn't bother me because I have the suspicion: Not all of these strange Nietzsche fans seem to have understood him correctly or want to understand him correctly. Nietzsche had foreseen this. In 1878, he wrote down under the heading “Im Strome”: “Strong waters sweep away a lot of rock and scrub, strong spirits many stupid and tangled heads. ”15

Source of the Article Image

Christian Saehrendt, Self-portrait as an artist, Oil on MDF, 100cm x 100cm, 2001, owned by the author.

Footnotes

1: Human, all-too-human II, Mixed opinions and sayings, 368.

2: Human, all-too-human I, Preface, 2.

3: Human, all-too-human I, 157.

4: Subsequent fragments 1888, No. 17 [3].

5: Cf. Paul Stephen: What is left-wing Nietzscheanism? Speech by Helle Panke Berlin 26.4.2018.

6: Cf. Sebastian Kaufmann: Nietzsche and the New Right. Also a continuation of the Conservative Revolution. Presentation at the conference “Nietzsche and the Conservative Revolution” (Ossmannstedt Nietzsche Colloquium of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, June 12-15, 2016 at Wielandgut Ossmannstedt).

7: “Nietzsche was a politically incorrect thinker”. Discussion between Andreas Urs Sommer and Korbian Frenzel, Deutschlandfunk Kultur.

8: Cf. Der Spiegel 30/2019, p. 38 f.

9: Cf. Felix Wemheuer related contributions to the panel discussion Is China closing itself off again? An inventory 40 years after the start of the reform and opening-up policy (Berlin 22/11/2018).

10: Hannah Lühmann: This Russian oligarch now wants to save Europe. world.

11: Jordan Mejias: I hate you guys. FAZ.

12: Cf. Daniel Pipes: The left is twisting Breivik's mental world.

13: Cf. Lukas Germann: The rest is just humanity! Black metal and Friedrich Nietzsche. Presentation at the conference “Pop! Goes the Tragedy. The Eternal Return of Friedrich Nietzsche in Popular Culture” (Zurich, 23/24/10/2015).

14: Mike Tyson: On Reading Kierkegaard, Nietzsche. Genius.com.