Caught in the Crossfire of the Culture Wars, There Stands Nietzsche

Comparing Two Current Perspectives

Caught in the Crossfire of the Culture Wars, There Stands Nietzsche

Comparing Two Current Perspectives

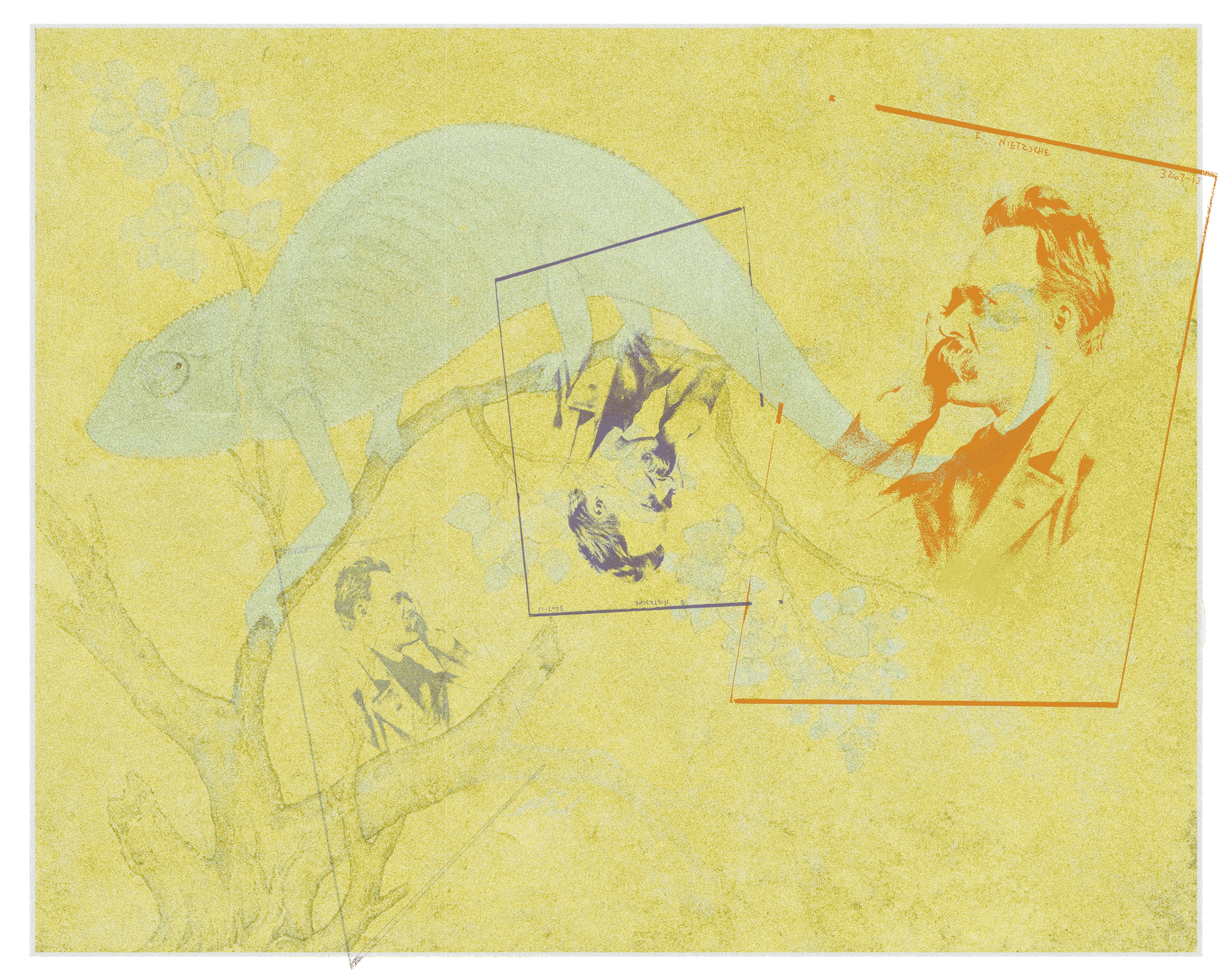

It is well known that Nietzsche's history of influence has been read and absorbed across all political camps. But what about our present tense? Paul Stephan examines the writings of two authors who are about the same age as himself, in their mid/late 30s, and whose perspectives on Nietzsche could hardly be more different: While French journalist and YouTuber Julien Rochedy declares Nietzsche a pioneer of a right-wing cultural struggle, the German philosopher and political scientist Karsten Schubert attacks him for a left-wing identity politics. Both positions do not really convince our authors; rather, they are entirely within the framework of the prevailing simulation of politics as a cultural struggle, which would need to be countered by focusing on the really pressing life problems of contemporary humanity.

Synopsis

Nietzsche placed himself on political issues in an extremely diverse and contradictory way. It is therefore no wonder that his thinking was subsequently adopted by a wide variety of political factions, from anarchists to Nazis. This has changed little to date, as two recent publications underline: Nietzsche — the contemporary by Julien Rochedy (2020/2022) and Praise for identity politics by Karsten Schubert (2024). While the former Front National politician and journalist Rochedy sees in Nietzsche a politically incorrect critic of left-wing identity politics and a thought leader of the right, the declared “left-wing Nietzschean” Schubert sees him precisely as an inspirer of a left. Remarkably, both are united by their strong reference to late Nietzsche and his power-theory analysis of the dualism of “master” and “slave morality” in the The genealogy of morality, from which, however, draw completely different consequences: Rochedy pleads for a new men's morality, Schubert reveals the criticism of slave morality.

Based on his own study Left-Nietzscheanism. An introduction (2020), in which he himself argues for left-wing Nietzscheanism, Paul Stephan compares these two approaches and highlights their respective weaknesses. Despite all efforts, Rochedy fails to sufficiently distance himself from historical fascism and the Conservative Revolution as its intellectual vanguard; he remains completely stuck in a particularist position. Schubert's alternative proposal of “particularist universalism,” however, suffers from the fact that he is unable to present a truly radical alternative to right-wing particularism. It remains in the same logic of identity-political cultural struggles, the simulation of politics as a spectacle of symbols, that afflicts our present day. Contemporary right and left Nietzscheanism is proving unable to present a radical alternative to existing global capitalism and even to ask the essential questions of humanity's future. They thus fall short of the level of Nietzsche's “big politics” on the “guideline of the body.” Political realism today means feeling, acting and thinking utopian and not participating in the “eternal return” of “master” and “slave morality.”

Full article

I. Nietzsche between the chairs of political modernity

As is well known, Nietzsche attempts in his writings to adopt an unpolitical, yes, anti-political position. Regardless of whether they are conservatives, socialists, feminists, liberals, nationalists, anti-Semites... they all get their fat off equally and become victims of “modern ideas.”1 branded. However, this does not prevent him from repeatedly making positive proposals to solve the pressing political questions of his time or at least from outlining approaches to political utopias, which, however, remain vague and therefore ambiguous in their political content: from “superman” to wild fantasies of new social hierarchies, “a new slavery.”2, up to the transfiguration of the Polish noble republic of the early modern period into an ideal anarchic state.3 Paradoxically, Nietzsche thus becomes highly compatible with almost all political ideologies of modernity: Because he distances himself equally from everyone, everyone projects their own ideas into him. You have to think of a coveted — or rather: desiring — woman; or in the words Nietzsche puts in the mouth of the feminine figure of “life”: “[I] her men always present us with their own virtues — oh, you virtues! ”4 Nietzsche as a seducer.

In recent times, the broad debate has been dominated by a relatively “moderate” image of Nietzsche as an individualist and critic of all ideologies — which, however, once again adapts him very much to the current post-modern zeitgeist, which the “great stories” Jean-François Lyotard spoke of as early as 1979,5 declared abolished and prefers to stick to pragmatic realpolitik in the name of values that are as non-binding as possible. Nietzsche as a “tame and civilized animal, [...] Hausthier”6 of the left-liberal mainstream. The “outdated” of yesteryear became the contemporary of today.

On the other hand, it is more exciting — and possibly: closer to Nietzsche's own intentions — to target Nietzsche for radical political projects that are directed precisely against this mainstream. How plausible is that? What potential does Nietzsche's writings have in this regard? And does Nietzsche lead us more to the right or to the left in this regard?

I myself have a two-volume book with the humble title in 2020 Left-Nietzscheanism. An introduction publishes that seeks to answer exactly such questions on the basis of an examination of Nietzsche's own writings (volume 1) and his history of influence, right and left (volume 2). There I tend to hold back with an unequivocal position of Nietzsche, but refer to the potential that he could have for left-wing theory and practice of the present day, for example in his plea for heroic individualism, in his accentuation of man's corporeality and dependence on nature, in his critique of resentful, small-minded left-wing in the form of “slave morality,” in his encouragement of departure and utopian thinking (keyword: “superman”), in his sharp diagnosis of modern nihilism culture, in its appreciation of authentic passion and carefree creativity. And much more. For me, “left-wing Nietzscheanism” cannot be an ideology — hence the indent — but rather an attitude that combines individualism and free-spiritedness with the struggle for universal values — which Nietzsche often, though not always, rejects (“universalism” — for me, in essence, being left-wing7). An attitude which, as the history of left-Nietzscheanism shows, can lead to a wide variety of practical and theoretical consequences, whether in the form of the anarchist approaches of Gustav Landauer and Emma Goldman, the Nietzschean Marxism of Ernst Bloch and the Frankfurt School, or the “left-Dionysm” of Georges Bataille and the Surrealists. In any case, the individualism of the left-Nietzschean actors is central, their striving for the combination of individual and collective liberation, which repeatedly brought them into conflict with the mainstream of left-wing parties and institutions.

In the meantime, two other remarkable works on the same subject have been published. What unites us is that we belong to roughly the same generation, even though our career paths are very different, and ask ourselves the same question: What follows from Nietzsche's philosophy for political theory and practice in today's social situation? And what unites us is that we are striving for answers that differ from the above-mentioned left-liberal mainstream. But that's where the common ground stops. Karsten Schubert demands in his recently published book Praise for identity politics based on his numerous articles published on this subject area in recent years8 Out of his “left-wing Nietzscheanism” (without a line), exactly a party for what I would describe, at least in parts, as the “resentment left.” For the French journalist, Julien Rochedy, a leading member of the National Front Youth Organization, in his book Nietzsche — the contemporary, originally published in French in 2020 and 2022 into German, it is clear that Nietzsche was a right-wing and therefore a pioneer of a completely different kind of “identity politics.”

II. A new far-right Nietzsche from France

Rochedy's book is a fairly compact introduction to Nietzsche's thinking, a popular philosophical work that largely does not contain references and also contains factual errors in some places.9 It is based on the three-hour presentation Nietzsche: Life and Philosophy, which Rochedy kept on YouTube in 2019 and reached 1.5 million viewers (link). As you can see, the former leading FN official, who generally has a very strong presence on social media and has published further books in the meantime, is not an intellectual loner, but a popular and influential figure in the milieu of the young radical right, whose theses should be taken note of for this reason alone, even if you disagree with them.

The book is easy to read and captivating, especially as Rochedy repeatedly interweaves anecdotes from his life and strong statements on current issues. He retells the most important stages in Nietzsche's life and talks about the content of his writings. However, it is noticeable that he, from the Birth of Tragedy Apart from that, the writings up to Happy science Just roam casually. He can probably still do something with the Dionysian aestheticism of the first work, but little with the Untimely Considerations and with the enlightenment pathos of the first three volumes of aphorisms10, they don't quite fit into his Nietzsche image. He even claims that Nietzsche dedicated the first volume of Human, all-too-human Voltaire was meant ironically11 which Untimely Considerations he dismisses as “premature considerations” (p. 35), which “are firmly based in a temporal context and are anything but “timeless” (ibid.). Nietzsche only really becomes interesting for Rochedy from Happy science and especially in his late work, for which he decidedly also includes the controversial collage edited by Nietzsche's sister and her collaborators The will to power counts. This is Nietzsche's, albeit “unfinished”, “main work” (p. 65), from which Rochedy extracts a “metaphysics of the will to power” (p. 68).12 He also gives a particularly detailed presentation of the core theses of The genealogy of morality.

Rochedy's guiding principle: You should recognize the “will to power” as an essential basic principle of all being and develop a power-affirming way of life on this basis. For him, “anti-racism, feminism, progressivism and socialism” (p. 97) are nothing more than “degeneration [s] and perversion [s]” (p. 74) of the same, ideologies which promise a rule-free society but must always introduce new hierarchies. He concludes: Get rid of hypocrisy — and demands a new European sense of power, an ethic of masculinity and strength in order to be able to counter the surrounding major powers and escape “decadence” within.

Rochedy is thus decidedly based on the Nietzsche interpretation of the “Conservative Revolution,” which includes right-wing intellectuals who, during the Weimar Republic, used similar arguments against it and who once more and less openly advocated a fascist overthrow of the hated democracy, such as Julius Evola, Martin Heidegger or Ernst Jünger. But there are also clear allusions to Thomas Mann's nationalist writings during the First World War, Alfred Bäumler and last but not least Oswald Spengler, who, like Rochedy, prophesied the “fall of the West” if there was no “life-affirming” renaissance of “men's morality.”13.

Of course, Rochedy is trying to distance himself from the “old right.” He promotes a united Europe — admittedly in decisive differentiation from the EU's “decadent” project — and criticizes imperialism and militarism, even speaks of the “absurd violence in two world wars” (p. 111). Rochedy wants to present an alternative to communism and left-wing ideology in general, but also to post-modernism, without therefore representing a fascist position.

However, this distinction from historical fascism is rather half-hearted in view of the obvious ideological proximity to it. How does Rochedy also want to criticize him when he rejects all modern values — human rights, democracy, social justice, etc. — as phenomena of decadence and excesses of “slave morality”? He dreams of exactly the same eruption of violence and archaic masculinity controlled by civilization. In the “new Europe,” white heterosexual men should clearly be at the forefront and everyone else should be granted inferior status at best. And when you then read sentences like “Is [...] a cleanly executed Uppercut Is it necessarily less' clever 'on the opponent's chin than the verbal counterargument? “(p. 154), there are really doubts about the serious bourgeois image that Rochedy is clearly striving for in his public self-presentation. His “new Europe” must be imagined as a copy of Putin's Russia, an authoritarian democracy in which perhaps basic civil rights — at least those that serve to maintain the capitalist economy — and formally even democratic institutions continue to exist, but in reality everything is done to keep a small elite of “masters” in power.

III. Nietzsche as a pioneer of left-wing identity politics

It is not surprising that left-wing identity politics and everything associated with it — political correctness, Wokeness, Cancel culture etc. — Rochedy is a particular thorn in the side. For him, Nietzsche is a politically incorrect person par excellence, whose “timeliness” results precisely from helping us to immunize ourselves against this ideology and to organize decisive resistance. One enemy image Rochedy repeatedly uses is the current intellectual left-liberal post-modern elite, whose alleged bodyhostility and physical neglect he repeatedly makes fun of when he writes, for example:

Nowadays, people like Plato [who is said to have been a broad-shouldered athlete; PS] in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, on Sciences Po or around Rue d'Ulm in Paris would undoubtedly be looked at with disparaging looks, because no one can believe anymore that the figure of a boxer could be more enlightened and clever than a slender sociologist or sloppy journalist with an egg-headed.14

Doesn't resentment itself speak from such sentences? — And this is just one of many examples of verbal provocation in Rochedy's book.

In any case, the doctorate in philosopher and political scientist Karsten Schubert is likely to appear to Rochedy as an exemplary member of this “elite” (which of course not It should be said that I would just like to start with Rochedy's polemic here!15). He has had a solid academic career so far and is currently working as an associate researcher at HU Berlin, with decidedly left-wing positions. His latest book Praise for identity politics In every respect, it reads as a diametrical alternative to Rochedy's theses.

It starts with the form: Schubert's book is written quite dry. His aim is not to captivate the reader with wit and polemics, but to convince him with good arguments. Schubert makes an honest effort to make a sober argument and in the book spends a lot of space on clearly defining his terms and fairly reflecting the positions of his opponents. The target group of the book is obviously an academically educated audience. His laudatory speech is surprisingly dispassionate. If Rochedy has to put up with the accusation of imobjectivity, Schubert's monograph is rather the opposite, often coming across as too instructive due to her academic style and thus missing its purpose of persuasion.

The point of Schubert's book is that he takes up numerous legal Nietzschean arguments also presented by Rochedy and also discusses them in detail in his study. However, he uses them in the sense of an avowed “left-wing Nietzscheanism”: He partially agrees with the Nietzschean critique of the universalism of modernity and, just like Rochedy, refers in particular to the The genealogy of morality and the power-theory considerations of late Nietzsche — always viewed from the perspective of Michel Foucault, arguably his most important thought leader — but picks up on these ideas to promote a redefinition of universalism. The classical universalism of Enlightenment philosophy and liberalism was in fact too blind to power relations and to the particular standpoints of individuals. Schubert now wants to overcome this limitation through a “particularist universalism,” which is about “grounding” classical universalism by repeatedly questioning the extent to which it really meets its claim and does not in fact only support the existing privileges of powerful groups. Schubert openly admits that this “left-Nietzscheanism,” in contrast to right-Nietzscheanism, is a rather loose connection to Nietzsche, based on the classics of post-structuralist theory.16

For Schubert, “identity politics” means the continuous and basically inexhaustible effort to “democratize democracy.” In the spirit of a “radical theory of democracy,” ever new oppressed groups should receive their fair share of democratic discourse and thus contribute to a continuous transformation of democratic institutions, which should become ever more inclusive. For Schubert, “identity politics” is therefore definitely the particular struggle of certain social groups (women, homosexuals, blacks, queers etc.) for more democratic participation and cultural recognition, but since these are the groups that have so far been neglected by the prevailing discourse, in this case, the particular struggle is also universal. For Schubert, not every interest policy is equally good; he distinguishes between a regressive “interest policy” that serves to expand and maintain one's own privileges — this would include the renaissance of “men's morality” sought by Rochedy — and a true progressive “identity policy,” which at the same time submits itself to certain normative standards with regard to its design and strategy. Schubert wants the real existing identity politics with his “praise,” i.e. decidedly none.”carte blanche“(p. 167), but rather develop criteria for how they can be criticized from within on the basis of their own claim — while at the same time it is clear that Schubert uses most forms of real identity politics, including language regulations (political correctness), Cancel culture and other often criticized problem areas, approves.

Against moral criticism of identity politics understood in this way, Schubert argues precisely that identity politics ultimately serves moral purposes on the one hand, but on the other hand, decisive power politics are necessary in order to enforce the concerns of the marginalized groups even against the will of a privileged majority. He makes no secret of the fact that identity politics in many cases means taking something away from members of privileged groups — but this is precisely necessary in line with the goal of “democratizing democracy” in order to overcome the much more serious oppression of disadvantaged groups. Schubert reflects very clearly that identity politics must therefore provoke sometimes angry defensive reactions, “resentment,” from the privileged.

What Schubert has explained in this context is the critique of “slave morality,” which for him is based on a false naturalistic understanding of “strength” and “weakness” and only serves to legitimize the privileges of the privileged. What Nietzsche calls “slave morality” is actually not a problem, but “actually forms the general core of politics” (p. 72). In truth, there are neither life-affirming masters on the one hand nor life-denying slaves on the other, but simply constellations of power to be considered soberly, whose change in the sense of a deeper democracy is important — and where planing is done, chips fall.

IV. Beyond correct and incorrect

Schubert and Rochedy's approach to Nietzsche is remarkably similar. At first, they both interpret Nietzsche as theorists of power, based primarily on analyses of late work and, last but not least, the The genealogy of morality. Against mainstream moralism and its transparent illusions, they plead for a decisive power struggle to push their own identity: Here the white “West” with clearly defined gender role models, there the “queer” otherness. There is, of course, a central difference: Schubert firmly adheres to universalism, to the left-wing project, and Rochedy does not want to know anything about all this. In Schubert's analysis, he pursues regressive interests, not emancipatory identity politics.

As different, yes: opposite, these views may be, they are based on a shared experience that is undoubtedly also that of late Nietzsche: the devaluation of all values in a reality seen as nihilistic, against the background of which the official moralisms appear to be hypocrisy. Of course, and also in agreement with Nietzsche, neither Schubert nor Rochedy draw the consequence of cynicism: rather, they both want to stick to values, in one case decidedly particularist, in the other case universalistic. “Gentlemen's morality” is also a moral. In this general attitude, both rightly claim the title “Nietzschean” and express an attitude towards life that is likely to be widespread. A feeling of disorientation and the search for new orientation — which, from the point of view of both, can only be achieved through submission to a collective ideology and through participation in a community. Both are equally opposed to the fashionable individualism of our time and the corresponding Nietzsche guidebooks for household use.

What I am now designing myself in the book I mentioned appears to me to be a qualitatively different alternative to these two approaches. Both Schubert and Rochedy are completely in the intellectual cosmos of late Nietzsche and his metaphysics of power — however broken experimentally and in perspective. Both are realistically moving in the paths of the existing society, whose adequate ideological expression is this metaphysics. They bring about the eternal return of the struggle between “master morality” and “slave morality.” Their fight is ultimately aimed at making “their own people” a better position within the hierarchy within the existing system: here the decent European boys and girls, there the cosmopolitan queers. But these are not all well-trodden paths Role modelsthat are suggested to us by the cultural industry itself? The woke intellectual and the “brave” politically incorrect as fake opponents whose mirror fencing can only be escaped by putting the fight in a completely different kind of arena.

What both Schubert and Rochedy lack is an insight into the economic roots of alienation, in one word: Marx. In Rochedy's book, he doesn't even play a role as an antipode; Schubert must somehow unify him as a leftist, but in this process he is forced to turn the critic of capitalism Marx into the pioneer of working class identity politics, i.e. completely reinterpret him.17 Unlike Nietzsche, they are also not interested in the materialistic questions of corporeality and ecology.18 They are, in the bad sense, culturalists and thus reflect the real problem of current politics: That it is never really about the really decisive issues — economic distribution, ownership, ecology — but rather side scenes that scratch the surface, but then political discourse revolves solely around (immigration, gender language, quota regulations, norms of political correctness...). Nietzsche himself wrote:

All questions of politics, social order, education are falsified down to the ground in that they took the most harmful people for big people — that they taught to despise the “small” things, that is, the basic matters of life themselves...19

This is not to say that the topics mentioned per se They are of secondary importance, but it is important to analyze them in the overall context of capitalist world society and not against the background of the culturalist analytical framework “Nihilism vs. Saving the West” (Rochedy) or “Privileged vs. Unprivileged” (Schubert), which, in their rude, contribute little to a precise understanding of these conflicts. It is obviously not only a small minority that is affected by the oppression of women, but it is important to determine exactly which economic interests the forced opening of the labour market for women serves and what additional burdens this leads to, instead of blindly taking the side of “women back to the stove” versus “women on the labour market.” The situation is similar with global migration flows, which can only be understood as part of the continuing exploitation of the global South by the North and the simultaneous “craving” of the industries of the capitalist states for workers. If you stick to the thinking template of “closing borders” vs. “open borders for all,” you lose the opportunity here too for a differentiated and nuanced analysis of this issue — and especially the development of convincing real political strategies on this issue: The right-wing perspective ignores the fact that mass immigration certainly corresponds to a certain economic necessity and must first show how it actually imagines maintaining the prosperity of Western nations without it; which Perspective of radical left-wing liberalism suppresses the fact that it serves very specific capital interests, which must first be understood above all questions of moral or political evaluation.

This culturalist self-dumbdown is a necessary expression of the apparent powerlessness in which we find ourselves: The general framework of the capitalist mode of production in its neoliberal form is more or less accepted without question,20 At best, agency is still experienced in the face of such cultural issues and moral skirmishes. In this respect, Schubert and Rochedy must equally be accused of failing to achieve their own claim to stimulate consistent power politics: rather, they are satisfied with the “small politics” set, without really the dimension of the “big politics” called for by Nietzsche, of radical utopias and alternatives,21 to look at. They both get stuck in what Nietzsche did in Zarathustra as the “noise of great actors”22 describes and admonishes: “They all want to go to the throne: it is their madness — as if luck were sitting on the throne! ”23

You don't have to be a conspiracy theorist to see in exactly this opposition of “political incorrections” and “woken” a spectacle that ultimately benefits one person in particular: the truly powerful. A banal example: Current feminism is just tearing itself apart in bitterly fought, often to the point of physical violence, between followers of queer feminism and traditional feminism, which starts from a biologically determined root of sexuality. In these, as you will assume, Schubert also locates himself in a very polemical and one-sided way on the side of queer feminism24 — and if Rochedy were to position himself in this conflict at all, his preference should be clear. But without this dispute having been artificially instigated for this purpose, it is clear that it objectively only amounts to dividing, weakening and rendering the feminist movement unable to act. And the same mechanisms can be observed in all sorts of other areas.

On the other hand, what needs to be done would be creative and life-affirming visions of a non-capitalist (and of course also: non-patriarchal, non-racial, reconciled with nature...) life that are strong and convincing enough to overcome the isolation and cultural division that is so characteristic of our time and which lead us to address the really important questions — the so-called by Nietzsche to focus on “small things.” Nietzsche is one of them: “Nutrition, location, climate, relaxation, the whole casuistry of selfishness”25, which for all People care about “basic issues of life,” which global capitalism threatens more today than ever before in history: Even in core capitalist states such as the USA and Great Britain, hunger and malnutrition — not to mention the absurdly simultaneous problem of mass obesity—are becoming mass problems again,26 Ever greater resources are being expended to forcibly maintain the repressive border regimes in the face of steadily increasing emigration pressure, the consequences of climate change are becoming ever more obvious, the cultural industry is shifting the capitalist pressure to perform more and more “into” our dwindling leisure time, “selfishness” is only welcome if it is that of the rich...

I do not mean any kind of alliance policy, but rather the cognitive and, above all, emotional focus on more important issues than those dictated to us by left and right identity politics (whether the latter is a “real” identity policy or not). I dream of such a movement; left and right identity politicians are torpedoing it in equal measure.

Nietzsche writes in the Happy science clairvoyant:

When I think of the desire to do something, as it constantly tickles and spikes the millions of young Europeans, all of whom cannot bear boredom and themselves, I understand that there must be a desire to suffer something in order to derive from their suffering a probable reason to do something, to do something. Emergency is necessary! Hence the cries of politicians, therefore the many false, fabricated, exaggerated “emergencies” of all sorts of classes and the blind willingness to believe in them. This young world demands From outside Should — not luck — but misfortune come or become visible; and her imagination is busy in advance to form a monster out of it so that she can fight with a monster afterwards. If these needy addicts felt within themselves the strength to benefit themselves from within, to do something to themselves, they would also understand how to create their own, self-own emergency from within. Their inventions could then be finer and their satisfactions could sound like good music: while they are now the world with their cries of distress and therefore all too often with the Nothgefühle Fill it up!27

Based on this, I would draw from Nietzsche's writings the essential lesson for our time to ask ourselves — each and every one of us in dialogue and dispute — the question of what for us real necessities are. It cannot be a question of authoritarizing what is essential and insignificant, but about entering into this process in the first place and the question Throw it up afterwards. I am, of course, confident that such a process, if it even got off the ground, would reveal certain answers that we could all agree on; major human problems that lie completely outside of what contemporary Right and Left Nietzscheanism is equally trying to praise us as the “most pressing” questions. Perhaps such a perspective would be conceivable that really lies beyond master and slave morality; a “master morality of slaves.”

For the background of the article image, those photograph was used.

Literature

Lyotard, Jean-François: Post-modern knowledge. A report. Vienna 2019.

Rochedy, Julien: Nietzsche — the contemporary. Dresden 2022.

Schubert, Karsten: Praise for identity politics. Munich 2024.

Stephen, Paul: Left-Nietzscheanism. An introduction. 2 vol.E. Stuttgart 2020.

Footnotes

1: See e.g. The happy science, Aph 358.

2: The happy science, Aph 377.

3: See the latter aspect my corresponding article on this blog.

4: So Zarathustra spoke, The dance song.

5: Cf. Lyotard, Post-modern knowledge.

6: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 11.

7: A minimal definition that Schubert and Rochedy also share. — In today's language, the terms “left” and “right” are unfortunately often used arbitrarily and based on mere lifestyle issues — and then, of course, declared obsolete after they have been emptied to the point of unrecognizability.

8: I won't go into detail about these articles, as the book is largely based on them. On the author's website Are they listed.

9: For example, Rochedy uncritically shares the Nietzsche family legend of the Polish origin of the name (see p. 22 f. & my article mentioned in footnote 3), claims that Richard Wagner only changed into a “nationalist, anti-Semite and Christian reactionary” (p. 35) in 1872 and presents it in such a way that academic German philosophy was still in the 1870s from Hegelianism and not from the New Kantianism was dominated (see p. 38).

10: Human, all-too-human, Morgenröthe and The happy science.

11: Cf. P. 38.

12: In reality, Nietzsche stopped working on that “major work” and the sister's falsifications are far more serious than Rochedy admits. See the relevant notes here.

13: Cf. the corresponding article by Christian Sährendt on this blog.

14: P. 47.

15: Why should it be particularly “body-affirming” to make a desperate effort to build a boxer's figure? And unlike in Rochedy's portrayal, the current cultural elite seems to me to be more characterized by their extreme efforts at “fitness” and hedonism. It is really body affirming to free oneself from such body images. — And it is obvious anyway that Nietzsche Rochedy's ideal type of boxing intellectual did not match. By the way, the left-wing anti-fascist Jean-Paul Sartre of all people was a passionate boxer.

16: Cf. P. 69.

17: Cf. p. 25. At the end of the book, he then pleads for an extension of identity politics around the axis Class (see pp. 183—187).

18: With Schubert, these topics are only marginally present or the body only from the limited perspective of Foucault's analysis of power, which must necessarily deny his pre-social life of itself (cf. also his mentioned rejection of psychology). — Rochedy talks a lot about a return to corporeality, but it only has the “strong”, trained body in mind, even if he is about an overly naive body cult alla Arno Breker distances (see p. 143). He briefly discusses ecological issues (see p. 156 et seq.), but more important to him than mentioning climate change is a critique of the harmful consequences of the “so-called [n] contraceptive pill” (p. 157).

19: Ecce homo, Why I'm so smart, 10.

20: At one point, Rochedy even praises the American author Ayn Rand, one of the most important thought leaders of radical neoliberalism (p. 142).

21: Cf. Ecce homo, Why I am a fate Am, 1.

22: From the flies of the market.

23: From the new idol.

24: Cf. p. 169 f.

25: Ecce homo, Why I'm so smart, 10.

26: In June 2023, 17% of all households in the UK were affected by moderate to severe food insecurity (spring), 13.5% of all households in the USA are hungry in 2023 (spring).

27: Aph 56.