What is ChatGPT Doing to Philosophy?

Attempt of a Critical Examination

What is ChatGPT Doing to Philosophy?

Attempt of a Critical Examination

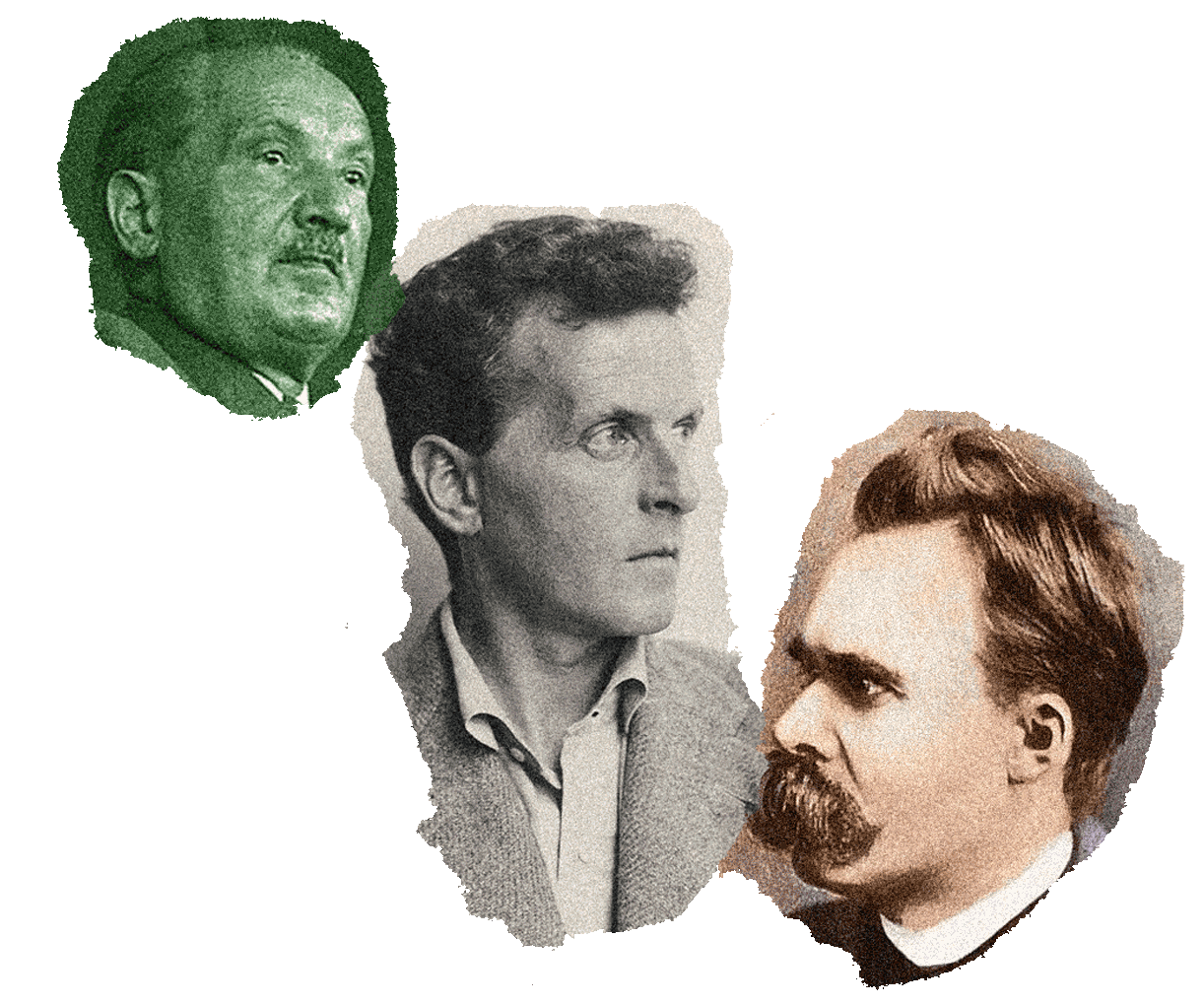

On the anniversary of Nietzsche's death, Paul Stephan conducted a detailed interview with the ChatGPT program on this blog to test the program's performance when it comes to profound philosophical questions (link). This is followed by a critical reflection of this experiment.

The images for this interview were, unless otherwise marked, with the software DeePai created. The instructions for the article image were “Nietzsche and ChatGPT,” the instructions for the images in the article “ChatGPT talks about Nietzsche.”

“The press, the machine, the railroad, the telegraph are premises whose thousand-year conclusion no one has dared to draw. ”1

I. An unusual “encounter”

What happens when you simply interview ChatGPT about Nietzsche? That's what I wanted to find out for this blog. The result was a dialogue that amuses you in view of the stupid mistakes that the program sometimes makes, but is also disturbing when you consider that the answers produced by the software are sometimes relatively accurate. It quickly becomes apparent: When it comes to writing stereotypically formulated texts fed with ill-thought-out Wikipedia knowledge, ChatGPT is pretty good, apart from one or the other gross blunder. I actually felt a bit challenged by the program to show that I am superior to it as a human author who has spent years thinking about the topics discussed. — The reader himself may answer whether I succeeded in that.

The pictures I created for these two articles quite well reflect the general mood in which dealing with the latest AI programs puts me: At first glance, these are almost too perfect pictures of Nietzsche and well-known photographs of him. For someone who doesn't look too closely and overlooks the numerous mistakes in detail — and is of course not familiar with Nietzsche's real face — they could easily be cheered as photographs of the philosopher. It gets particularly creepy when you look at the pictures very carefully and ask yourself what these “Nietzsches” are actually looking at...

So the “all clear”: ChatGPT is still not capable of truly creative ideas. All you get served is a bland stew of truisms and commonplaces. In view of the numerous factual errors and the major problems that the program obviously has when dealing with secondary literature, I would not even recommend using it for school essays, let alone university assignments. You can't even be sure that an orthographically and grammatically correct text will be spit out. In any case, these texts cannot be used without critical examination. For serious authors, ChatGPT could perhaps be used as a research tool to find out what the average opinion is on a topic. So what you exactly not Write and which phrases you should absolutely avoid. In particular, the new competition could serve as an incentive: Real authors must now make more effort to stand out from the mass-produced goods produced by AI.

II. Man and machine as an artistic team

Either way, it is important to calm down the sometimes somewhat heated discourse on the latest AI. It should be regarded neither as an exaggerated threat nor as a savior, but as a tool that, when it comes to usage texts, can certainly serve as an inspiration when it comes to more complex requirements. With Nietzsche — who could not even have imagined the existence of computers, but at least experimented enthusiastically with the then completely new typewriter and finally returned to handwriting in disillusionment2 — would we have to speak of a non-resentful perspective on these innovations: We cannot change the existence of these programs anyway; it is now a matter of dealing with them as productively as possible.

As is so often the case, art is a pioneer. From April 25 to May 12, the exhibition curated by Kati Liebert and Olga Vostretsova took place in the Leo Schwarz foyer of the Gewandhaus in Leipzig Walk on the Carpet where 13 students from the local Academy of Graphics and Book Arts presented their work. No less than three of these very diverse works from different artistic fields aggressively used artificial intelligence as a means of the creative process.

Tobias Kurpat fed an AI with the piano music by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy to create a new piece that could be listened to with headphones. The installation also included the score of the new composition and a 3D print of an unnaturally twisted hand, possibly that of a musician. This work had a disturbing effect on me. I expected a composition by Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. A wild sound structure, more reminiscent of ragtime or free jazz, awaited me, which made me doubt my knowledge of music history. It wasn't dissonant, but it didn't follow any real musical structure either. Had the composer had fun there? Only reading the accompanying text, which I felt compelled to do, provided clarification. Composing in the style of a specific composer is probably not (yet) one of the strengths of AI.

While Kurpat's work primarily had the function of demonstrating the technical possibilities of AI-based composition for me, two of his fellow students went one step further and used it for works of art whose subject is not AI itself. Susanne Kontny used an AI tool to feminize portraits of the Gewandhaus's consistently male bandmasters. The masters became champions. Manually generating these images in similar deceptively real quality would certainly have required some effort. Here, however, the question is whether the work of art is really convincing, apart from the fact that the possibilities of AI are demonstrated in a funny way: Its intended statement is quickly understood, the countless portraits serve merely to illustrate a political indictment.

Toni Braun took a different path, with whom I also spoke in detail about the process behind her installation Celestial Urging stood. She used AI to generate an oversized portrait of a female figure. It was apparently not so easy to write the instruction in such a way that the desired result was achieved and then to find exactly the right figure among the many suggestions in the program.

However, even Toni Braun did not simply let the AI rule, but used a painting by Nathaniel Sichel as a model, The Beggar from the Pont des Arts. The result is as disturbing as the Nietzsche portraits I created for this article and the composition in the style of Mendelssohn Bartholdy. At the very first glimpse, I would have let the AI fool me again. But on closer inspection, this is a rather “monstrous” figure that is difficult to label, a hybrid that questions our viewing habits — but not only that at the same time: The impression of a self-confident young musician who presents herself here remains. The ornaments that frame the printed banner allow multiple interpretations. Is it perhaps even the Nietzschean vision of a “superwoman” who, in her contradiction, affirms herself and lets this affirmation radiate outward, even though her instrument, which is difficult to define, is unlikely to produce any sounds and her limbs are crippled? But the barbed wire also seems to indicate the suffering that is necessary to gain such an identity — or is it a protective armor? Are we perhaps even dealing with a female warrior rather than an artist? But the tassels, borders and glass chandeliers also suggest preserved femininity. It seems to me that the work shows the complex situation in which (not only) women face today when they want to assert themselves “militarily” and therefore strive for toughness while maintaining softness and creativity.

The mix of art and AI can therefore certainly lead to interesting works if you use the latter wisely as a means to expand the scope of your own creativity. Such a “monster” as the hybrid nature of Toni Braun's installation would hardly have been able to give birth to even the most flourishing purely human imagination — and at the same time it could not have been created without human input.

Perhaps this approach to AI would also be exemplary for text production and philosophy? For example, you could try to engage ChatGPT in a Socratic dialogue. Or have it write aphorisms, some of which may be interesting and can be expanded upon. Last but not least, Nietzsche's own practice teaches that the creative process — whether in art or in philosophy — is in large measure not just inventing but finding and arranging. In Human, all-too-human In this sense, he criticizes the belief in sudden inspiration as the origin of the work of art: “All great workers were great workers, tireless not only in inventing but also in rejecting, viewing, redesigning, arranging. ”3 In other words: A successful spiritual creation is always too a remix of existing material — and Nietzsche did the same when writing his writings. He tirelessly wrote down his own ideas, but also those that he received while reading others' texts. Sometimes he uses individual phrases made by others quite indiscriminately — without quoting them, of course.4 “Talent Borrows, genius steals,” is Oscar Wilde's maxim, which could also go down as Nietzsche's aphorism — and Zarathustra explains accordingly: “Is it not more blessed to receive than to give? And stealing is even more blissful than receiving? ”5 — Why not get inspired by AI and incorporate AI-generated material into your own works or texts? Similar to the typewriter, Nietzsche would probably have experimented with artificial intelligence quite impartially — even though he might have set it aside as unusable after a few weeks. Similar to what is taken for granted today, Google, Wikipedia or sites like nietzschesource.org or The Nietzsche Channel to be used as an aid in your own text production.

III. Disadvantages and side effects

But of course, using AI is not without problems. First of all, writing texts or producing works of art is a process that has value, a process of learning and experience. Students in particular, who — as my own experience as a lecturer unfortunately confirms — are now increasingly using artificial intelligence to create their work, end up harming themselves in particular. Authors and artists not only want to produce something that has an effect on others, but also want to go through the process of creation and grow from it. And conversely, the recipient's enjoyment consists in participating in this creative process through his own understanding, even if he is only present in a mediated manner as a result. A novel that you would know was not the result of years of effort and processing of personal experience, but was written in a few hours on the basis of a quickly written prompt, will be read with less interest, if you want to read it at all, even if the AI should be able to imitate profound novels in a few years. It remains an imitation after all. An authentic work depends on the fact that it was a person who wrote it and who wanted to express something in it.

This does not rule out the possibility that it could be very common in a few years to have usage texts or images of favor generated by programs. But this would in fact make work easier and would create free time to produce real works. Perhaps the use of AI for this purpose will soon be as common as the use of spell checkers or translation programs is today. Even when translating complex philosophical works, it is common today to transfer the “rough work”, which requires little intellectual capacity anyway, to the software and to let the human translator only do the “fine-tuning.”

In order to approach this prospect calmly, it may be helpful to look at the example of chess. Computers have long been able to play this game more successfully than us. But this fact has not diminished the enthusiasm for it; on the contrary, it is currently experiencing a new wave of popularity, fuelled by social media and online portals such as lichess.org and chess.com. Mastering the “Game of Kings” is still considered the epitome of human creativity and intelligence. Because even though you can't beat an advanced chess computer as a human for a long time, the value here too lies not simply in the result, but in the game itself. Watching a game between two chess computers is just as boring as reading a volume of AI-generated love poems if you're not interested in their performance. But there is an intrinsic value in playing and looking at other players that the AI will never be able to destroy. At the same time, chess players use the new possibilities of technology quite freely to train their skills, analyze games and develop new strategies. Here, too, the software only appears to be a threat and in reality simply helps to increase human capabilities. ChatGPT can't play chess by the way — challenging it to a game can cause some irritation and exhilaration. That is at least a weak consolation: The super computer, hyped everywhere, fails miserably because of a task for which computers actually seem to be predestined.

In any case, chess programs or the new algorithms are just an expression of our own abilities. Modern AI systems are only as good because they have been fed with data produced by us for years. They only reflect our own collective creativity and intelligence. We should not be afraid of them or even fall into a feeling of inferiority towards them, but rather be proud of what we have achieved as a species.

But it is precisely this fact that points to another problem: The results of the AI are a combination of a program and the material with which it was trained. But only companies that own the rights to the software code currently earn money from it, not the countless authors of the training material — and of course those who use AI to produce commercial products. The authors of the training material were not and are not even asked for permission. This is morally questionable and unfair; it is about genuine expropriation, which may also have legal consequences.

This development, at the latest, makes it overdue to rethink ways of appropriate remuneration for people who make their works openly available on the Internet and without whom the Internet would not function at all as a huge catalyst for creative and intellectual developments. Those who earn money with AI should be forced to pay a levy whose income goes to the authors of the input material used.

IV. Conclusion

In keeping with the theme of this text, I would like to leave the final word to ChatGPT myself, which, at my request to write an aphorism in the style of Nietzsche, gave the following answer, which, although not razor-sharp with the topic discussed here, is all too easy to apply to it: “In the depths of the soul, the shadows of the past dance, but only the brave recognize the possibilities of morning light in it. ”

footnotes

1: Human, all-too-human II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, 278.

2: Cf. this summary on the website of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

3: Human, all-too-human I, 115.

4: This applies in particular to the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, whom Nietzsche read intensively and enthusiastically and repeatedly borrowed individual phrases and thoughts from him, but only mentions him sporadically in his published writings.