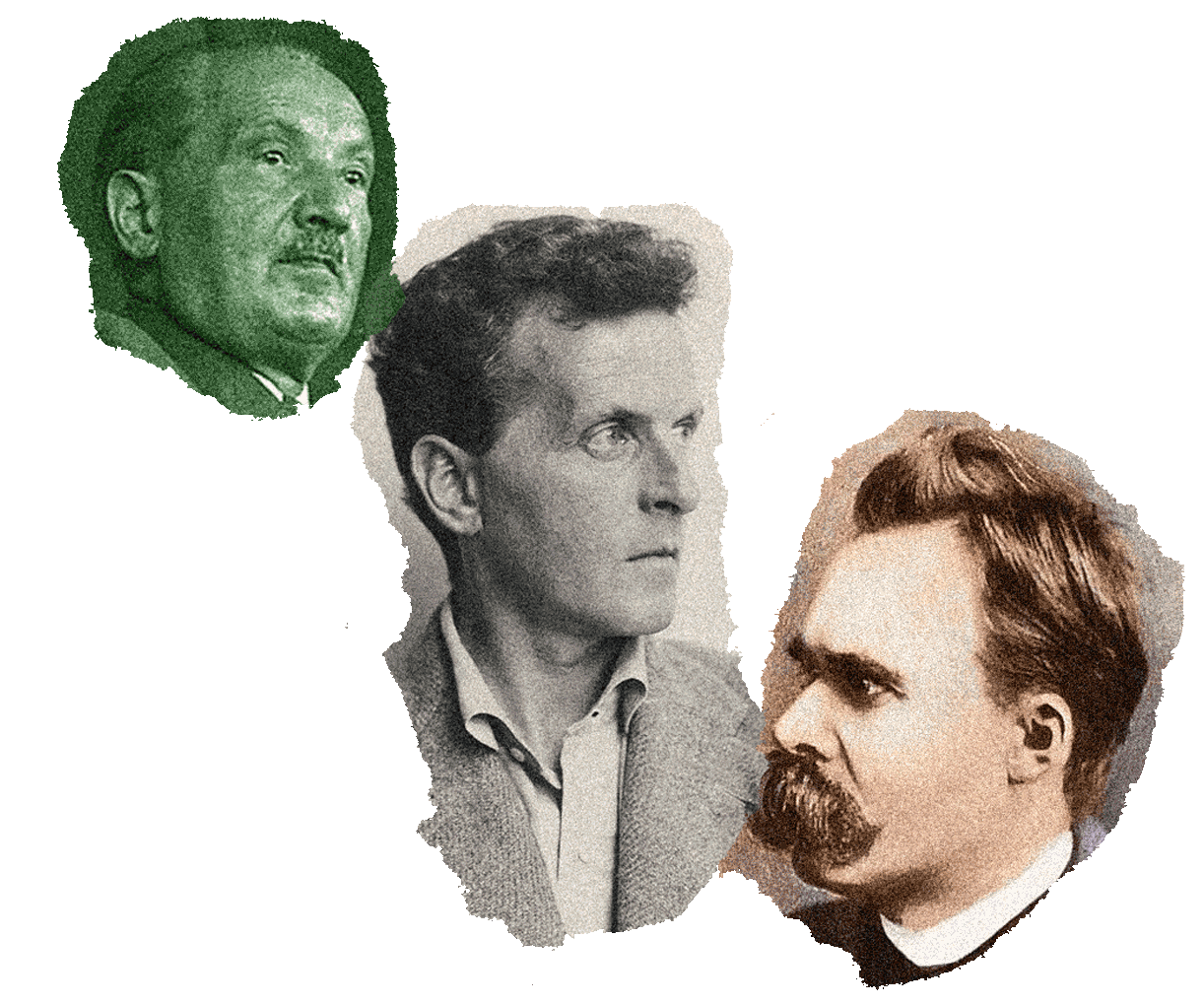

Nietzsche Against the Body’s Naysayers

A Conversation with Philosopher and YouTuber Jonas Čeika

Nietzsche Against the Body’s Naysayers

A Conversation with Philosopher and YouTuber Jonas Čeika

After discussing Jonas Čeika's book How to Philosophize with a Hammer and Sickle and bis YouTube channel (CCK Philosophy) (link), Henry Holland interviewed the American about the blockages of academic philosophy, Nietzsche's relevance as a thinker on the “guideline of the body,” and about tensions between his claim as an anti-philosopher and his social position.

Henry Holland: Jonas, could you tell readers here in Germany and Switzerland, who may not know your influential philosophical YouTube channel, about your career and how it came about that you now write and explain about Nietzsche and the Left? In your book published in 2021 How to Philosophize with a Hammer and Sickle, which unfortunately has not yet been translated into German, you are exploring the question of why today's academic philosophy is so dominated by a depersonalized approach. And you even trace this trend back to the 1950s, when “[Senator Joseph] McCarthy's academic henchmen [...] pushed academic philosophy away from the more ambitious task of a critical and reflective self-image. ”1 Here, a depersonalized philosophy was deliberately used as a method to reduce the risk of left-wing “subversion” of the Academy. Do you also see your decision six years ago to invest your time in building up your now highly regarded YouTube channel instead of giving preference to a conventional academic career in the same context? Did your understanding of the decision depend on how academic philosophy lets people down today?

Jonas Ceika: I started my YouTube channel during my bachelor's degree in philosophy at NTNU [Technical and Natural Sciences University of Norway]. Back then, I was interested in both left-wing politics and cultural theory written in the 20th century — and my channel only began to become popular when I created a Video response to Jordan Peterson's understanding who produced postmodern philosophy.2 Without the knowledge and insights I gained in the academic world, my channel would certainly have been impossible, because it was only there that I dealt with political philosophy and cultural theory.

Yet I am frustrated by this tendency towards hyper-focused thematic concentration in academic philosophy — a symptom of the general trend towards specialization in the late capitalist division of labor. The overwhelming flood of available information forces scientists to specialize in a very limited field. Certainly, this is often a necessary step; but with the reduction of all scientists to their role as highly differentiated specialists, there is little room left for analyses of social totality and broad-based social conditions, as carried out by Marx and Nietzsche. These two personalities were not subject to the usual academic constraints. Specialization often comes at the expense of the larger context.

A more significant problem, however, is the isolation of academic intellectuals from the wider society. Here too, Nietzsche and Marx are exceptions, but even highly academic philosophers of early modernity, such as Kant and Hegel, had immense influence on the thinking of the wider society. Today, philosophers rarely achieve this kind of influence, and when they do have it, it is often due to factors outside the academic world. In the 2020s, scientists — partly due to the very narrow focus mentioned above — tend to write almost exclusively for other scientists. Specialists therefore write primarily for other specialists. This creates fenced academic bubbles into which people without a higher university degree can hardly find any way into. But when you research the writings of philosophers who sought a comprehensive transformation of society or culture, it seems like a falsification to simply allow their work to become the subject of an academic niche. Presenting theory via YouTube enabled me to reach millions of people, which would have been highly unlikely in the ordinary, formal role of a scientist. In addition, this medium freed me from the academic constraints of a restrictive specialization. This is not to say that YouTube doesn't have its own constraints and pitfalls, for example due to the algorithm used there or because of the other mechanisms that determine the reach of individual videos. But being able to reach a larger audience than usual still gave me a different sense of the importance of my philosophical studies than I would otherwise have had.

HH: The publication in English of Domenico Losurdo's monumental intellectual biography of Nietzsche in 2020 was a major event in recent Anglophone Nietzsche research and was only one year before the publication of your own book. (The German translation, Nietzsche, the aristocratic rebel, was published by Argument Verlag back in 2012.) Even though you don't directly address Losurdo's arguments in your book — as they were not yet available in the main phase of writing the book — has Losurdo's work brought about changes in the way you read Nietzsche in the meantime?

JC: There is no end to secondary literature on Nietzsche. When I first became aware of Losurdo's book, I was already in the final stages of my writing and did not have the time to organically integrate a replica of Losurdo into my book.

I admire Losurdo's Nietzsche research, but at the same time find it quite reductive. Every philosopher is a kind of multiplicity that can be approached from a variety of perspectives, and what is classified as essential or even random with regard to a philosophy depends on the perspective that you take at a particular point in time. Losurdo tries Nietzsche on one to reduce this starting point, namely to his rejection of socialism and working class politics. Certainly that is one productive point of view, but by no means the only one, and something is always lost as a result of such a reduction, especially with such a multi-faceted philosopher as Nietzsche. An example: Losurdo contextualizes Nietzsche's career in light of his reaction to the Paris Commune, which, in Losurdo's opinion, gave all his later works an essentially anti-socialist character. The idea is that anti-socialism is not just one of many aspects of his work, but is the basis for all of Nietzsche's mature works. But that falls short. In one of Nietzsche's notebooks from 1877, which he wrote a few years after the events of the Paris Commune, Nietzsche spoke positively about socialism, which he described as “the highest morality.”3 At the time, he did not use the term “morality” in a pejorative sense. From Losurdo's point of view, this note can only be rejected as incoherent or inconsistent with the rest of his body of work, but that is exactly what makes such an approach reductive. He is just one of several possible perspectives and is therefore unable to fully grasp the meaning, effect and possible uses of Nietzsche's writings.

Presenting the entirety of Nietzsche's philosophy as a specifically anti-socialist philosophy is more than just reductive. It also limits the new and creative possibilities offered by Nietzsche's works. As I described elsewhere, my Nietzsche book is intended more as an event and less as a presentation. And the events that his writings can produce far exceed their original political context.

HH: Early in Hammer and Sickle Do you describe Nietzsche as a philosopher of individual, human bodies. You suggest that this focus makes Nietzsche an exception among canonical Western philosophers, who have mostly ignored or spoken ill of the body. And although you point out that French philosophers, following on from 1968, did successfully bring the body into philosophy, you also emphasize how the Anglo-American tradition largely overlooked this innovation. You portray this latter tradition as one in which the body rarely acts as the center of agency or agency is understood. Do you like something about the interfaces between Nietzsche, the body and agency Tell me? And also something about how do you react when you introduce Nietzsche as a philosopher of the body to contemporary polemics and debates? For example, the trans* policy, which is primarily fought at universities in the Global North, is also a politics of the body. How do you reconcile this phenomenon with your understanding that the Anglophone university milieu continues to marginalize the body as such?

JC: Although the body in broad parts of Anglo-American academia is thoroughly theorized, it is important that a large part of this theorizing comes from Literary Theory Departments4 or sociology institutes, not from institutes of philosophy. Sometimes this theorizing even comes from faculties of art or from political activism on university campuses. Many changes are also taking place in the sedate philosophy institutes. But there is still a great deal of support among Anglo-American philosophers for the idea that philosophy is ultimately an incorporeal enterprise. Many subject areas that focus on Anglophone, analytical philosophy continue to operate fairly intellectually — at least in terms of which style and content are actually allowed.

The trans struggle is interesting because it is to be interpreted as an interface between body and “gender”: here, gender is understood both as a set of social gender norms and as an ideology. This struggle is particularly fruitful when it is related to material concerns, and concerns of particular social classes. For example, when it comes to access to healthcare and housing for trans people. Here, the body acts as a kind of transmitter to metaphorically represent the social situation, which combines particular interest (gender identity) with universal interests (the need for health and shelter).

HH: Both for you and for leftists who are on “the other side” of the Nietzsche debate, it remains instructive what this philosopher can tell us about wage labor and the concerns of specific classes. You summarize, for example, that Nietzsche's pension — received from the University of Basel from the age of thirty-five after he left his job there due to illness — “enabled him to spend the rest of his life without having to engage in paid work or commerce. ”5 You also suggest that this position “outside” of the payroll system and the business world gave him extraordinary insights. Sue Prideaux, author of the Nietzsche biography published in 2018 I am Dynamite!, however, points out that Nietzsche only received this pension for six years, i.e. until 1885, and that it was substantial but not a fortune: 3,000 Swiss francs a year.6 This limited reference period prompted William Schaberg to the thesis that writing for Nietzsche was after all contract work, which he promoted commercially.7 His main publishers, Ernst Schmeitzner and E.W. Fritzsch, paid Nietzsche a flat fee of usually 30 or 40 Reichsmarks per printed sheet, in addition to his royalties from sparse sales.8 According to Schaberg, this piecework fee, which was the equivalent of around 37 francs at the same time, or roughly over 1% of his annual pension, offered Nietzsche a great incentive to write. Nietzsche's “meager sales figures” were also far higher than those of most US or German university philosophers during their lifetime in the 21st century: 22,900 copies of Nietzsche's works were sold by 1893.9

Do such misunderstandings contribute to a mischaracterization of Nietzsche as an extraordinarily privileged person who was not affected by the restrictions on wage labor? And would you like to position yourself on Daniel Tutt's claim that Nietzsche is primarily

appeals to a class of readers who have an ambivalent and often disparaging relationship with the working class and the class struggle in a wider sense. Nietzsche tends to address those who are collectively referred to as the petty bourgeoisie in Marxist class theory, and who assume a contradictory class position defined by their non-relationship to productive work.10

This claim is apparently contrary to the survey carried out in 1897 for the Leipzig Workers Reading Room. This revealed that Nietzsche's texts were borrowed by workers far more frequently than those by Marx, Lassalle and Bebel.11 Do such compulsive intra-left debates, which play off productive work against non-productive work, harm the building of wider alliances for the abolition of capitalism? And could you trace the same debate back to Nietzsche?

JC: It is true that Nietzsche's pension was nowhere near the end of his life. But when he received no further payments from 1885, he only had three years of his career as an author with regular publications ahead of him. So we can say that most of his career was supported by his retirement — and that this privileged position contributed to the socially distanced nature of many of his writings. Even after his pension expired, he was financially supported by friends and family. So he never had to seriously worry about his livelihood.

From his personal perspective, it is probably true that Nietzsche earned more than just symbolic sums from selling books. Nevertheless, these sales figures occasionally remained so poor that his work could not arouse any interest among publishers. For example, in the fourth part of Zarathustra, who was not interested in his publisher because he rated the book's commercial opportunities as extremely low. That is why Nietzsche repeatedly invested his own money in publishing his books. And he usually sent free copies to a small circle of readers known to him personally. It testifies to the value he attached to his writings that he was willing to lose money in order to circulate them.

Although I have no doubt that Nietzsche's royalties were of great importance to him personally, they were certainly not a capital investment. For these reasons, Nietzsche would certainly not be considered a productive worker in the strict Marxist sense — although he could be regarded as a merchant of goods! But that in no way makes his work less important. Perhaps even the opposite. His very unconventional writing required a high degree of independence and benefited from the fact that it was neither necessarily profitable for publishers nor was it commissioned by capital.

As you correctly note, Daniel Tutt's claim of the dominant petty bourgeoisie of Nietzsche's first readers, given how popular Nietzsche's works were among the workers. I also doubt the validity of Tutt's characterization of the petty bourgeoisie as a class that is “indiscriminate from productive work.” The petty bourgeoisie is very well able to do productive work and can therefore relate to it in the same way as the upper bourgeoisie.

In Anglophone Marxist circles, there is a very heated debate about productive as opposed to unproductive work. The most damaging way to conduct this discussion is a moralizing one, which transforms these economic categories into value judgments. This transforms them from categories used by Marx and Engels to explain how capitalism works into categories of moral evaluation. This often leads to a reactionary imitation of wage labor. Productive workers are those who create added value — not less, but also no more. It has nothing to do with categories of justice or nobility. And so-called non-productive workers, as well as unemployed people, play a positive role in class struggle and emancipatory politics in many cases.

HH: To bring together our many threads of conversation: Do you regard philosophy and other peer-to-peer education, which is taught via YouTube videos, as a microcosm of accelerationism? Could this medium overcome the traditional contradictions of learning in capitalist societies? To this day, a tiny number of permanent professors have had a major influence on philosophical and socio-political debates. While most students and laypeople experience these discourses, through which they should educate themselves, as such in which they can never have a voice — and which they therefore do not need to master. Can you talk about your experience building your Patreon community of now around 1,000 members who contribute one or five or ten dollars a month to help you earn a living while researching and producing the videos? How would you compare this model with Nietzsche's own experiences and strategies in building his community of readers? Are the intellectual freedoms that this working model offers you your primary motivation for the choice? Or are you primarily motivated by the experienced opportunity to reach hundreds of thousands more people than you would have achieved in a traditional role as a university teacher or professor?

JC: In Hammer and Sickle I describe the “technological sublime” as a new potential that capitalism has made available to us.12 And I have no doubt that the speed of communication made possible by this is incredibly valuable and has opened up new educational, cultural and aesthetic opportunities — including new spaces for philosophy and theory that are not tied to a territory or an academic institution. You can compare my Patreon community to Nietzsche's community of readers, but they are clearly differentiated by the speed of feedback and the pace of interaction between author and audience. In some situations, even due to the more diffuse border between transmitter and receiver, which is temporarily abolished. When working on the Internet, I really like the fact that I can immediately follow the thoughts and discussions that my contributions initiate. These in turn serve as inspiration for new videos. That is why I see myself as much more influenced by my audience and less isolated from them than Nietzsche, which has both positive and negative consequences.

Even before the development of the Internet, some social theorists imagined a future horizontal form of communication and cultural exchange in which the border between sender and recipient would be abolished in favor of social reciprocity. The Internet has made this possible on a larger scale than ever before. However, this entire emancipatory potential has been blocked and concentrated on a few powerful multinational corporations which, in alliance with various governments, have focused all this immense potential on advertising, data collection, and surveillance. I think we can barely imagine what opportunities a socialized Internet could create for us.

Jonas Ceika is a writer living in Norway. He studied philosophy at NTNU (Norwegian University of Technology and Natural Sciences) and in 2018 founded the “CCK Philosophy” channel on YouTube, which is now subscribed to by over 283,000 interested people. Čeika also works as a screenwriter and producer for his channel. In addition to numerous videos about the interfaces between politics, philosophy and critical theory, his book and other publications include How to Philosophize with a Hammer and Sickle: Marx and Nietzsche for the Twenty-First Century (London 2021).

Henry Holland (born 1975) is a literary translator, from German into English, and lives in Hamburg. He also writes and researches the history of ideas and culture and published in 2023 on Ernst Bloch and Rudolf Steiner in German Studies Review. Together with religious scholar Aaron French (University of Erfurt), he is working on a critical biography of Steiner in English. You can find out more about Holland's scientific work and cultural policy on his blog, German books, reloaded, or in Print newspapers. He is a member and board member of Hamburger Writers' Room: The working space for literary writers in Europe.

Sources

Ceika, Jonas: How to Philosophize with a Hammer and Sickle. Nietzsche and Marx for the Twenty-First Century. London 2021.

Pancake, August: What does the German worker read? Answered based on an enquiry. Tübingen 1900.

Prideaux, Sue: I am Dynamite! A Life of Nietzsche. London 2018.

Schaberg, William: The Nietzsche Canon. A Publication History and Bibliography. Chicago 1995.

Tutt, Daniel: How to Read Like a Parasite. Why the Left Got High on Nietzsche. London 2024.

Footnotes

1: Ceika, How to Philosophize, P. 40.

2: Note HH: Čeika's “Peterson” video has been viewed over a million times since its release in 2018.

3: Note HH: Nietzsche's complete sentence, however, also leaves open contradictory interpretations: “Socialism [sic] is based on the decision to equate people and to be fair to everyone: it is the highest morality” (Subsequent fragments 1876, No. 21 [43]).

4: Note HH: not identical to German-language literary faculties, but similar.

5: Ceika, How to Philosophize, P. 71.

6: Cf. Prideaux, Dynamite, chapter 10, e-book location 16.55.

7: Schaberg's book contains numerous examples of how Nietzsche renegotiated the fee for each publication with his publishers and repeatedly expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of fees. Cf., to mention just two such examples, The Nietzsche Canon, pp. 48 and 56.

8: For example, Schmeitzner Nietzsche wrote on September 21, 1883 (see Schaberg, The Nietzsche Canon, p. 96) that he should receive 40 Reichsmarks for each of the 7.5 printed sheets that”Zarathustra II“would contain. At this point, it helps to remember that a printed sheet generally comprised 16 book pages.

9: For more information on selling Nietzsche's books, see the review of Schaberg's book here.

10: Daniel Tutt, How to Read Like a Parasite, P. 153.

11: Cf. August pancake, What does the German worker read?

12: Cf. Ceika, How to Philosophize, P. 209.