“Poland is Not Yet Lost”

Germany's Neighboring Country as a Political Utopia in Nietzsche's Posthumous Writings

“Poland is Not Yet Lost”

Germany's Neighboring Country as a Political Utopia in Nietzsche's Posthumous Writings

The late Nietzsche repeatedly imagines himself as a descendant of Polish nobles. It is not just a personal whim, but also says something about Nietzsche's philosophical positioning: For him, Poland is a kind of “anti-nation,” a people of “big individuals” — and last but not least, the Polish noble republic is the political utopia of a radical democratic community, which, precisely in its failure, corresponds to his idea of “aristocratic radicalism.” Paul Stephan goes in this Long Read explores the deeper meaning of this topic in Nietzsche and questions his transfiguration of the old Rzeczpospolita: From a political point of view, this is not as desirable a model as Nietzsche suggests. Jean-Jacques Rousseau continues to lead in this regard Considerations on the Government of Poland from 1772.

I. The 'Poland complex'

“I am a Polish nobleman pure sang [pure blood; PS], to whom not even a drop of bad blood is added, least of all German. ”1 Apart from the superlative of this statement — which can almost be described as' Trumpesk 'from today's perspective — Nietzsche certainly had reasons to believe in his Polish origin, which was repeatedly emphasized in letters and in his estate from 1880. In any case, as he reports several times,2 He is repeatedly considered one of their own by exiled Poland and had his Polish origin confirmed by a document from an alleged genealogist.3 Even his sister shares this family legend. The core argument of the two is that their family name, which sounds a bit Slavic-sounding on the first listen, is actually derived from the Polish “Nietzky.” In the 18th century, one of their ancestors was elevated to count by Augustus the Strong, but had to leave the country after his death due to his Protestant beliefs. Max Oehler only proved in the 1930s — not without, of course, the problematic interest in identifying Nietzsche as a “pure-blood” in the sense of Nazi ideology — that this entire story could be a mere fantasy that should give the family a certain exotic sparkle and, last but not least, a drop of blue blood.4 In particular, the pastor's family had to confirm their identity that they were descended from a martyr of Protestantism. Perhaps the legend is therefore also the background to Nietzsche's famous sentence from 377. Aphorism of Happy science:

We are, in one word — and it should be our word of honor! — good Europeans, the heirs of Europe, the rich, overburdened but also overrichly committed heirs of millennia of the European spirit: as such, they also outgrow and reject Christianity, and precisely because we out They grew up to it because our ancestors were Christians of the reckless righteousness of Christianity who willingly sacrificed good and blood, status and fatherland to their faith.

This sentence shows in particular what Nietzsche might have been another reason for his obsession with his Polish origins: In the course of the 1870s, he became more and more alienated from the Bismarck Empire he despised, subjectively and objectively, and saw himself as a wandering cosmopolitan, as a “good European,” as an eternal homeless person. His desire to be a Pole meets this need for ever greater detachment from Germany — but at the same time reveals the desire for a new home, a new identity bond. At first glance, there seems to be a certain contradiction between the two impulses — but only at first glance. On closer inspection, they turn out to be quite compatible with each other.

II. The posthumous fragment

What is the nature of this new identity, which Nietzsche only discovered in Ecce homo public, but which plays a not insignificant role in private statements as early as 1880? What does it mean to him to be a Pole? An estate fragment written in 1882 and rarely noticed in research provides information about this, which is worth looking at in its entirety:

I was taught to trace the origin of my blood and name to Polish nobles, who were called Niëtzky and gave up their homeland and nobility about a hundred years ago, finally avoiding unbearable religious oppression: they were Protestants in fact. I do not want to deny that as a boy I was no small proud of my Polish descent: what of German blood in me came only from my mother, from the Oehler family, and from my father's mother, from the Krause family, and it wanted to seem to me that I had remained essentially Polish. It has been confirmed to me often enough that my appearance is Polish; abroad, such as in Switzerland and in Italy, I was often referred to as Polish; in Sorrento, where I spent a winter, the people called me il Polacco; and especially during a summer stay in Mariánské Lázně, I was reminded of my Polish nature several times in a remarkable way: Poles came to me, greeted me in Polish confusing and confusing with one of her acquaintances, and one before whom I denied all polenthum and whom I myself as Swiss introduced, looked at me sadly for a long time and finally said “it is Still the old race, but the heart turned God knows where.” A small notebook of mazurcas, which I composed as a boy, had the inscription “Our old forders in mind! “— and I was mindful of them, in various judgments and prejudices. The Poles seemed to me to be the most gifted and chivalrous among the Slavic peoples; and the talent of the Slavs seemed to me higher than that of the Germans, indeed I thought that the Germans had only joined the ranks of gifted nations through a strong mixture of Slavic blood. It was good for me to think of the right of the Polish nobleman to overturn the resolution of an assembly with his simple veto; and the Pole Copernicus seemed to me to have made only the greatest and most worthy use of this right against the decision and inspection of all other people. The political irrepressiveness and weakness of the Poles, as well as their debauchery, were evidence to me of their talent rather than against it. In particular, I revered Chopin for freeing the music from German influences, from the hange to the ugly, dull, petty bourgeois, tappish, important: beauty and nobility of spirit and in particular noble joy, exuberance and splendor of the soul, as well as the southern gluth and heaviness of feeling had not yet been expressed in music before him. Compared to him, Beethoven himself was a semi-barbaric creature whose great soul was poorly brought up, so that she never really learned to distinguish the sublime from the adventurous, the simple from the lowly and disgusting. (Unfortunately, as I will now add, Chopin has grown too close to a dangerous current of the French spirit, and there is quite a bit of music by him that comes across as pale, sun-poor, depressed and richly dressed and elegant — the stronger slave has not been able to reject the narcotics of an overrefined culture.)5

One should not be fooled into thinking that this fragment is written in the past tense. This entire complex of topics plays absolutely no role in Nietzsche's estate, including his childhood and youth writings, before 1880. In fact, it seems that Nietzsche only thought of remembering this family legend because he was mistaken for a Pole.

In any case, in 1877, in a letter to his girlfriend Malwida von Meysenbug, he reported that he got along very well with two Polish ladies during a stay at the spa, without even addressing his own Poleness with one syllable.6 And in 1878, in an estate fragment, he wrote down, interestingly enough, the opposite of what he wrote down five years later:

Poland is the only country of Occidental Roman culture that has never experienced a renaissance. Reformation of the Church without reforming the entire spiritual life, and therefore without establishing lasting roots. Jesuitism—noble freedom is ruining it. That is exactly how the Germans would have felt without Erasmus and the humanist impact.7

In short: In this fragment, Nietzsche is concerned with the fiction of a continuous way of seeing that has existed supposedly since childhood, which is intended to hide the stark breaks that his thinking experienced again and again. During his student years, he was still an ardent Prussian patriot, admirer of Bismarck and sympathized with German nationalism until the early 1970s.

Why was Nietzsche thought to be a Pole in the first place? In view of the frequency with which Nietzsche reports on such encounters, this story is not implausible, however suspicious one might be of the self-stylization Nietzsche sometimes engaged in in his letters. In 1884, he met in Nice with his girlfriend Resa von Schirnhofer, who wrote a remarkable report on this encounter in 1937, which gives an extremely vivid impression of how Nietzsche affected his contemporaries. It states:

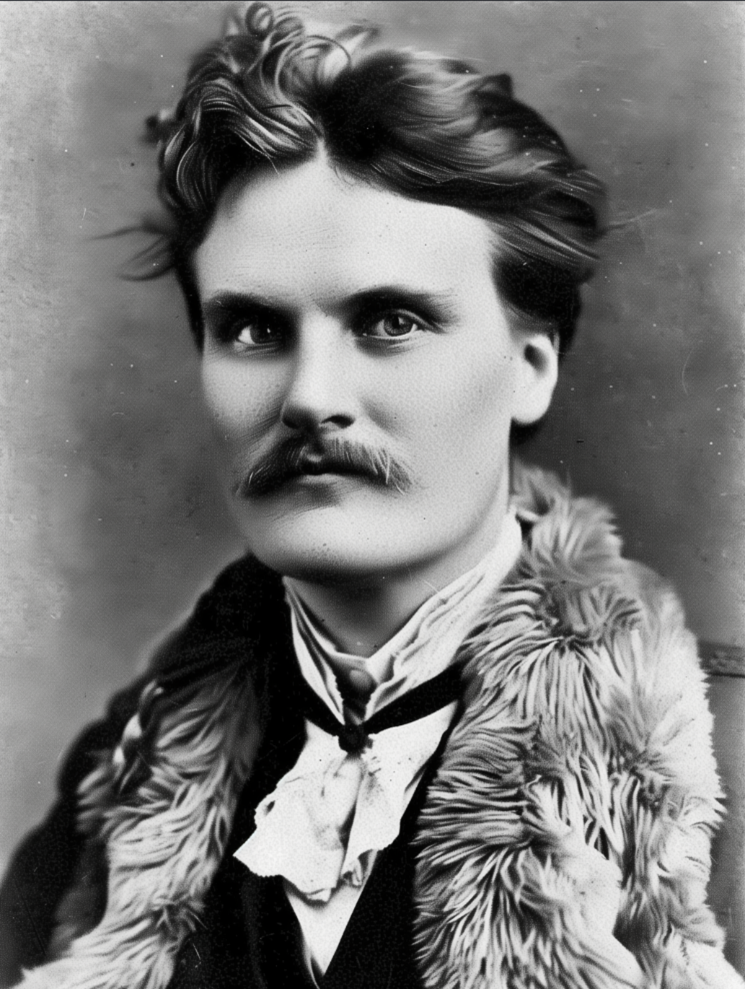

Back then, the [presumed Polish origin of Nietzsche; PS] was new to me and interested me, as I had seen characteristic shape-related heads in a historical painting by Jan Matjeko's [sic] in Vienna of a resemblance that existed not only superficial in mustache growth, which I had also said to him, which he seemed very pleased about. Because he was very proud of his Polish character physiognomy.8

In making this statement, Schirnhofer is particularly likely to refer to Matejko's paintings Sobieski near Vienna thought (cf. the article picture), which was exhibited there in view of the 200-year anniversary of the victory of the united Christian Army on September 12, 1683 against the Ottoman army that had besieged Vienna. At that time, the Turks suffered a crashing defeat, which sealed the fall of the Ottoman Empire. An advance by his elite cavalry commanded by the Polish-Lithuanian King John III Sobieski was decisive for the Christian victory. A Polish achievement that many self-proclaimed 'saviors of the Occident' still find difficult to recognize today. In 1883, it was in any case a veritable provocation to show this painting in view of the non-existence of the Polish nation state in Vienna, which was intended precisely as such by the nationalist Matejko. Contrary to the usual customs of the time, the painting could be seen free of charge and he had an explanatory pamphlet printed with patriotic content.9

The beard dress of the king and his knights is in fact confusingly similar to Nietzsche's walrus beard. And this is not an isolated case: This type of beard has a long tradition on Polish royal portraits.10 Von Schirnhofer downplays the role of beard in her report, but there is some evidence that it was he in particular who led the Poles to think of Nietzsche as one of their own. However, this must not lead to the fallacy that Nietzsche let his schnauzer grow for this reason. On the contrary, there is much to suggest that student Nietzsche may have copied his now iconic beard from the most famous wearer of this extremely eye-catching type even then — the later Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.11 Prussia had therefore become a Polish beard.

This transformation is no more a contradiction than the mentioned simultaneity of Nietzsche's self-definition as a Pole and as a “good European.” Because the Poles are considered Nietzsche right now as a nation of free spirits, of “great [n] individuals.”12. A paradoxical “anti-collectivist collective,” which is particularly notable for its remarkable constitution. When you realize that even the young patriot Nietzsche admired Bismarck above all because he regards him as a “great individual,” a political genius to his liking (a rating that remarkably continues to be found in his writings even after his break with the Reich), then it becomes clear that his beard should express one thing above all else: his own belonging to that illustrious circle “large Individuals” who, in his opinion, should direct and direct world history. So if Nietzsche's sister should claim on the occasion of the outbreak of the First World War: “Bismarck is Nietzsche in cuirassier boots, and Nietzsche, with his doctrine of will to power as a basic principle of life, is Bismarck in a professor's skirt.”13, that is by no means completely unjustified. But unlike in the case of Heidegger's embarrassing mustache from 1933,14 It would be wrong to infer a political affinity between the two from the visual resemblance between Bismarck and Nietzsche's beard: Nietzsche worships Bismarck and his policy of “blood and iron,” which he even revered in Beyond good and evil expressly welcomed as a southern antidote to the “spirit of the North,”15 not because it is nationalistic politics, but for similar reasons, for which he admires Goethe, Napoleon or even Copernicus and the Poles par excellence: Because they all correspond to his idea of “great individuals” who are concerned about the opinion of the “mob”16 Disregard and a truly”tall Policy”17 operate in the sense of “life” (ibid.).

III. Individualistic (anti-)politics

Like hardly any other, the estate fragment is suitable for clarifying the problems of Nietzsche's conception of the “great individual.” For now, it seems like a commitment to an almost anarchist individualism, which only has the catch of being limited to the nobility. Nietzsche even goes so far as to protect the individual's attachment to the stability of the community: For him, the fact that no state can be made with a consensus democracy is no argument against this form of political form, quite the opposite. At the same time, however, he does not plead for completely uninhibited individualism, as he associates it, for example, with German petty bourgeoisie and French decadence: His preference is not simply for individuals per se, but big Individuals whose greatness he associates with chivalry, beauty of the soul and aesthetic taste — which, however, is not an actual virtue at the same time, as he also celebrates the dissolute and irrepressible character of the 'Polish soul. ' You can see that his definition of “greatness” is rather vague here as elsewhere: Beethoven, whom he otherwise transfigured as one of the greatest geniuses,18 Is now suddenly devalued what exactly the resemblance between Chopin, Copernicus and Polish nobles should exist, is facie completely unclear. In any case, he uses himself, and this is the crux of the matter, primarily esthetic Criteria for a politic Verdict — moral and, in the usual sense, political criteria are ignored and even decisively devalued.

In this fragment, Nietzsche obviously oscillates between two moments that otherwise determine his thinking as well as his history of political influence: First, that of radical individualism, which makes him interesting for anarchists — on the other hand, that of the aesthetic transfiguration of an aristocratic “master morality,” which refers to his fascist reception. In this passage, Nietzsche is leaning towards the anarchist rather than the fascist pole — and yet it does not result in praise of universalized indiscriminate freedom.

IV. Utopia and Reality

It is hardly possible to adequately appreciate the 'Poland Fragment' if you do not consider whether it relates to any historical reality at all or whether it is a typical Nietzsche half-truth or even fiction. In this case, however, the 'fact check' is surprisingly in favour of the poet-philosopher: During the period of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic, which lasted from the 16th century until the dismantling of Poland in the late 18th century, Polish society was in fact characterized by individualism that was probably unique in history. In any case, all members of the nobility — around 15% of the population19 — met on equal footing and were able to participate equally in a political system that included elements of consensus and even council democratic elements. At the noble meetings, every member could actually veto all decisions of the meetings — which not only meant that they withdrew a resolution, but that the entire assembly had to be dissolved and no longer had a quorum. A regulation which — as you might expect — is regarded by most historians as one of the main constitutional reasons for the fall of Poland.20 As early as the middle of the 18th century, even republican voices such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who in response to a corresponding request made a comprehensive proposal to restructure the Polish state, were of the opinion that that “liberum veto” was absurd and had to be eliminated as quickly as possible.21 In fact, it not only resulted in the paralysis of all political decisions: Both the high nobility and even foreign powers made targeted use of it to corrupt the Polish state and increase their influence. A seemingly democratic settlement was in fact an instrument in the hands of the most powerful.

The time of “golden freedom” was, to put it bluntly, a time of darkest lack of freedom for all those who did not belong to the nobility and on whom the nobles were allowed to exercise their arbitrary freedom. While the noble meetings — Nietzsche is probably alluding to this — often degenerated into wild drinking binge with hearty fights, the vast majority of the population lived in abject poverty. Extraordinary social inequality, oligarchic rule behind a radical democratic façade, which Rousseau clearly laments. If you look at the political reality of old Poland, then the romantic image that Nietzsche paints of him quickly fades away. It is more an example of a particularly bad than a particularly successful political order according to all usual criteria. Only Nietzsche's aestheticized look makes them appear somewhat acceptable.

Rousseau believes that the problem is not the right of veto per se is. But, according to him, it does not work in a society that is characterized by social inequality and antagonistic particular interests and in which there is therefore no strong sense of cohesion. In particular, he believes that the development of patriotic heroism is necessary to save Poland from destruction: Every individual should be prepared to sacrifice himself for the fatherland. This idea has a superficial resemblance to Nietzsche's emphasis on chivalry and grandeur of the old Poles, but Rousseau does not involve any individualism, on the contrary: as a result of Rousseau, each individual should see himself not primarily as an individual but as a Pole. It is moral heroism, whereas in Nietzsche's case it is amoral.

Rousseau's critique of Polish society is based on pragmatic political criteria on the one hand — his aim is to preserve the Polish state — and on the other hand from the ultimate moral purpose of all politics, which he had already achieved in 1762 in Social contract articulated: A society without masters and servants, in which general and particular interest coincide. His considerations were incorporated into the Polish Constitution of 1791 — which was too radical for the surrounding absolutist monarchies so that they immediately occupied and divided Poland among themselves. (They had been able to live with the old constitution of “golden freedom” earlier.) — And they were also an important source of inspiration for the revolutionaries of 1789, who were mostly ardent admirers of the “citizen of Geneva.”

V. Conclusion

It may be recognized that Nietzsche's praise of chivalric self-will and aristocratic excessiveness is a legitimate antidote to the petty bourgeoisie of modern societies. The late Rousseau, on the other hand, propagated a nationalism that appears highly problematic from a liberal perspective and which should have an inglorious history of influence in the 19th and 20th centuries.

But the bottom line is that Rousseau is right: Consensus democracy is a model that makes no sense in an antagonistic society; Poland's “golden age”, celebrated by some liberals to this day, was in fact one of corruption, of social anarchy in the worst sense of the word and not exactly of cultural flourishing outside of Nietzsche's excessive imagination. Copernicus not only lived before the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic, it is also completely anachronistic to attribute him to one of the later established nations. He probably saw himself primarily as a subject of his employer, the Prince-Bishop of Warmia. Chopin, in turn, lived after the break-up of Poland; his father was French and France was his main place of activity.

“Old Poland” is a romantic place of longing, but it is not a desirable political utopia. Even in this fragment of the estate, which at first glance seems quite likeable, Nietzsche does not exactly show his brightest side. What is remarkable, however, is how he succeeds in both criticizing the shallowness of modern individualism and questioning modern collectivism. The tremendous potential and radicality of his thinking lies in this ability to merge very different, yes: contradictory, perspectives. But when it comes to political thinking in the strict sense of the word, it is probably better to stick to Rousseau.22

Sources

Benne, Christian: Liberum veto. How democratic is Nietzsche's aristocratic radicalism? In: Martin A. Rühl & Corinna Schubert (eds.): Nietzsche's Perspectives on Politics. Berlin & Boston 2023, pp. 161—180.

Ders: Tell yourself. In: Ders. & Dieter Burdorf (eds.): Rudolf Borchardt and Friedrich Nietzsche. Writing and thinking in terms of philology. Berlin 2017, pp. 95—111.

Dabrowski, Patrice M.: Commemorations and the Shaping of Modern Poland. Bloomington & Indianapolis 2004.

Janz, Curt Paul: Frederick Nietzsche. A biography. Vol. I. Munich & Vienna 1978.

Oehler, Max: To the Nietzsche family tree. Weimar 1939.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques: Considerations on the Government of Poland and its proposed reform. In: Socio-Philosophical and Political Writings. Munich 1981, pp. 507—561.

Ders: Of the social contract or principles of state law. In: Socio-Philosophical and Political Writings. Munich 1981, pp. 269—392.

Schirnhofer, Resa from: From the person Nietzsche. In: Journal of Philosophical Research 22 (1968), PP. 250—260.

Summer, Andreas Urs: “Bismarck is Nietzsche in cuirassier boots, and Nietzsche... is Bismarck in professor skirt”. In: Journal of the History of Ideas VIII/2 (2014), p. 51 f.

Stephen, Paul: Significant beards. A philosophy of facial hair. Berlin 2020.

Article image

Jan Matejko: Sobieski near Vienna (1883). Image source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schlacht_am_Kahlenberg#/media/Datei:Sobieski_Sending_Message_of_Victory_to_the_Pope.jpg.

Footnotes

1: Ecce homo, Why I'm so wise, 3.

2: See, for example, the report from his girlfriend Resa von Schirnhofer (From the person Nietzsche, P. 252). Nietzsche reported on this anecdote in at least five letters in the 1980s. To his important correspondent Georg Brandes He writes approximately on 10/4/1888 Right at the beginning of a short curriculum vitae: “I am usually considered Polish abroad; the list of foreigners in Nice's comme Polonais listed me this winter.” For a complete list of those letters, see my own book Significant beards, p. 101 et seq., where I have already explored in detail the connection between Nietzsche's beard and his “polentum” described here (see ibid., pp. 102—105).

3: Cf. Yanz, Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. 1, p. 27 f.

4: Cf. Oehler, To the Nietzsche family tree.

5: Subsequent fragments 1882, 12 [2].

6: Cf. Letter from 4/8

7: Subsequent fragments 1878, 30 [54].

8: From the person Nietzsche, p. 252. In Mentioned letter to Brandes <k>Nietzsche also writes himself: “I am told that my head appears in Matej O's pictures. ”

9: Cf. Dabrowski, Commemorations, p. 59 f.

10: Consider something like Matejko's Portrait of King Stanisław Leszczyński or The list of all kings and dukes of Poland on Wikipedia. In the 20th century, the nationalist Polish dictator Józef Piłsudskian continued this tradition — and thus looks almost confusingly similar to Nietzsche in some portraits (see e.g. this photo).

11: See also how about the relationship between Bismarck and Nietzsche in general, in more detail Stephan, Significant beards, PP. 95—99.

12: Subsequent fragments 1884, 29 [23].

13: Quoted after summer, “Bismarck is Nietzsche...”, P. 52.

14: See that there pictured photo and also Stephan, Significant beards, p. 69 f.

15: Cf. Aph 254.

16: Subsequent fragments 1888, 14 [182].

17: Subsequent fragments 1888, 25 [1].

18: That's what it's called in a very typical estate fragment: “Beethoven, Goethe, Bismarck, Wagner — our last four great men.” Here Nietzsche praises “the monological secret divinity of Beethoven's music, the self-sound of loneliness, the shame while still being loud...” (ibid.) Not a word from Chopin.

19: Cf. The corresponding entry on Wikipedia.

20: For a first overview, see the corresponding article on the English-language Wikipedia.

21: Cf. Rousseau, Considerations on the Government of Poland.

22: For a somewhat more benevolent, contradictory presentation of Nietzsche's enthusiasm for Poland, cf. the corresponding research contributions by Christian Benne (Tell yourself and Liberum veto).