Determining Nietzsche

Determining Nietzsche

Does Nietzsche have clear philosophical doctrines? There is still a fight with Nietzsche's ambiguity today. When does he mean what he says? In her essay, Natalie Schulte explores the question of where, in the midst of assimilating ambiguity through ideological programs on the one hand and academically savvy dispersal of Nietzsche's thought structures into indiscriminate and incoherent fragments and perspectives, on the other hand, today's engagement with Nietzsche has to locate its decisive challenges. Between the dangers of confusing his philosophy and the limitless relativization of his theses, she is looking for a fruitful third way of dealing with the question of the “actual Nietzsche.”

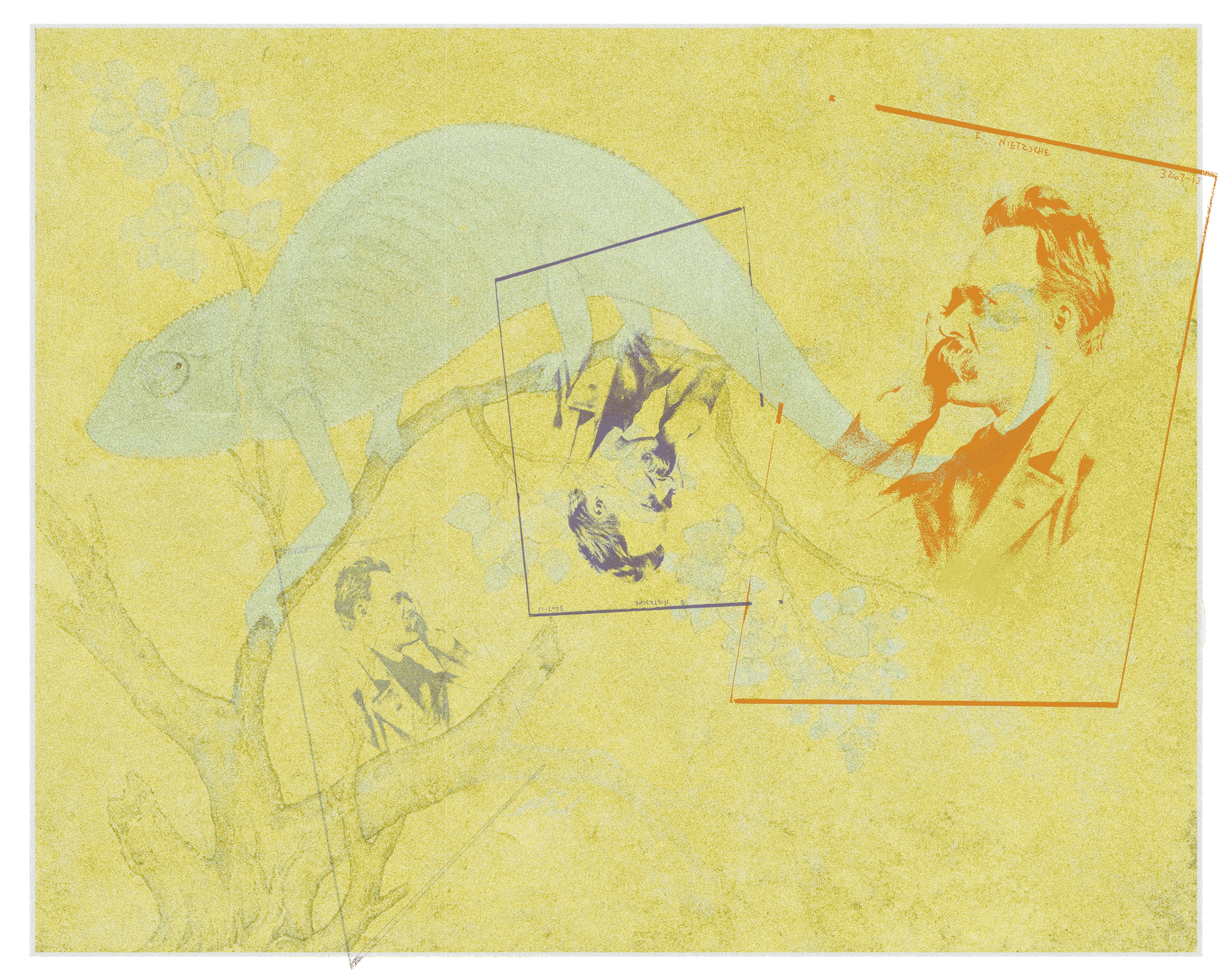

The accusation that Nietzsche can be claimed for and against all views has long been popular because he constantly contradicts himself in his works and both represents and attacks any opinion, so that there is no “actual” Nietzsche left — at most the one that the respective reader wishes for himself as a friend or, depending on the case, as an enemy. Nietzsche a white wall? A projection screen for wishes? Kurt Tucholsky probably put this in the strongest possible terms:

Who can't make use of Nietzsche! Tell me what you need and I'll get you a Nietzsche quote in return. [...] For Germany and against Germany; for peace and against peace; for literature and against literature — whatever you want.1

Anyone who deals with Nietzsche for a long time cannot help but ask themselves whether Tucholsky did not speak the most appropriate word with it. For in the never-ending hunt for Nietzsche's actual philosophy, a lot of contradictory things have already been said: that it prepared the spiritual ground for National Socialism, that it culminates in the three main doctrines of “superman,” the “idea of eternal return,” and the “will to power,” that her critical potential should be rated higher than her affirmative, that she is an “artist metaphysics” “It is only considered an individual philosophy that the “tragic idea” is the common thread of Nietzsche's entire philosophy Go through — just to pick out a few interpretations here.

We could also venture to assert that no position has hitherto been absurd enough not to find a role model in Nietzsche and not at least one quotation as proof in his work. Nietzsche a womanizer and enemy of emancipation? Not so hastily — how much room for development does he give women, and couldn't his genealogical method become an important tool of feminist theory? Nietzsche regrets that Protestantism brought an end to so many Catholic excesses — but not Christianity? Well, somehow all aversion makes you feel Nietzsche's secret admiration for Luther and his attitude of “I'm standing here and I can't help myself.”

Nietzsche on the right and a Chauvi, a reactionary, anti-liberal, anti-humanist block of wood? By no means, the only thing missing was a tender father's hand, so that the male fantasies of power overshot the mark here and there. But with a bit of fine work, we chisel out the more subtle and, excuse the repetition of the word, “actual” principles and recognize, lo and behold: Nietzsche is a leftist, a flawless democrat, a philanthropist. Incognito perhaps even for ourselves, but in the service of the “good cause” (whatever it is), and our purpose as a good and foolhardy interpreter will be to use the red thread not to shimmy out of the maze into freedom, but into the heart and mind of the philosopher.

Surrender to incoherence

But let's put the irony aside. Nietzsche is rightly regarded as an unsystematic philosopher, and naming the core ideas of his philosophy can be quite a headache. In view of all the opposing attempts to determine the essence of his philosophy, it might seem advisable to be more modest and simply to prove that all the previous provisions prove to be reductions that are far more in line with the interpreter's wishes than Nietzsche's philosophy. Because always — always (?) — it would be possible to find a counterexample or a subtle counter-interpretation that casts doubt on every statement, no matter how clear. We therefore no longer claim that there is a core of his philosophy or a vein that splits into many small, rich secondary veins, but which all draw blood and life from the same center. We try to make Nietzsche more questionable and dive into a game of references and references, as serious researchers we name sources and delve into reading traces of Nietzsche's own reading. An overall picture looks outdated, requires a central perspective that we have already switched off the light a long time ago, while we claim that Nietzsche is more like one of those interchangeable images in which you see either a woman or a vase. And if we really still wanted to stick to the metaphor of the maze, then it would probably be painted by Maurits Cornelis Escher and would have neither entrance nor exit, neither heart nor center, but only a multitude of Minotaurs who draw themselves from two-dimensionality into a strange three-dimensionality, as if they themselves were still underlining that they were simply handmade.

In a sense, those who first set out in search of Nietzsche's actual philosophy have already mapped out the further path of Nietzsche research. With each fixed portrait, the tilted image had to be negated and shown that it was ironically broken, or just an independent attempt, or could be embedded into the overall picture. This method of initially particular undermining was finally perfected, universalized and finally scientified by parts of recent Nietzsche research. But now every statement about his philosophy slips into our fingers. In a gigantic process of corrosion, his philosophy runs the risk of dissolving into individual atoms, and there is more space from aphorism to aphorism: “Will we still find a bridge? Is there another way over? Is there another place to go? “May we ask that with a bit of Nietzschean tragedy

Philosophy as a fragmentary hodgepodge

Or, as a sober mind might object, is there no danger at all? Isn't the magic of Nietzsche's enduring modernity precisely in the fact that every time creates its own Nietzsche? In the age of ideologies, it was naturally a Nietzsche of Zarathustrian doctrines, today a cuddly ambivalent philosopher of the one-side—on the other hand, not to arrest, always one step ahead, always dazzling, never reaching for. With a superior smile, we can watch new experts beginning Nietzschein interpreters still hailing for a firm statement. Well, they may not yet know the first sketch or the second revision before the published aphorism. If we multiply the interpretation options by each amended article per section, let's try inverting the signs once and remember that minus multiplies minus plus. A comma shakes up recent research today more than the question of whether Nietzsche rejected the idea of the Second Coming as a failure.

But what is dealing with Nietzsche's philosophy other than an ingenious gimmick in a hermetic academic space in which experts knowingly play the balls to each other? You don't take anything seriously yourself anymore. And doesn't the academic discourse at our universities suffer from this? They no longer believe: that truth can be named, that morality is enshrined in heaven, that philosophy changes the world. Clarified, philosophy now appears as the product of a completed digestive process of recent history, socio-cultural framework, established mentality and politics, which the rest of the population can confidently ignore. A philosophy that is about to give up its essential claims to knowledge becomes a mere archive, an increative institution that no longer dares to search for truth at all, but simply presents new aspects of an ingenious chronology of interesting ideas.

But even this criticism is perhaps too short-sighted and does not do justice to the current state of philosophy. Which philosophical school could still be convincing? Who seriously and wholeheartedly wanted to call themselves a Kantian? And anyone who has ever met a Heideggerian knows that they would rather not become one either. This raises the question: What can an established philosophy be for our future thinking? And how can we approach a philosophy like Nietzsche's today?

Philosophy as critique

We can fairly barely avoid appreciating recent Nietzsche research for the fact that, as a corrective, it puts an end to the many simplifications in Nietzsche interpretations and refutes precisely those who brag loudest about his name: The self-optimizers and shallow life counselors and, of course, as ever, the political right who cannot refrain from making Nietzsche their own with a handful of keywords.

From his philosophy, we can certainly learn skepticism about closed philosophical systems. It is tempting to defend a thought-building, once painstakingly constructed, against the doubters to the best of our ability. But it's all too easy to become a prisoner of the architecture that you brought into the world at 35. In Nietzsche, we find an authentic certificate of thought that shows how to move away from the past without worries, and throw away what appears too tight and outdated. In this respect, with and through Nietzsche's philosophy, we learn how to think independently, but not a closed teaching system. Of course, this does not avert the risk of arbitrariness. The attempt to find a far-reaching perspective in Nietzsche cannot be insignificant, and stimulates an intellectual effort that turns out to be far more exciting than the self-righteous agreement that allows Nietzsche's thinking to break down into atomistic individual statements that only stand alone and could at most be placed in a subjective context.

Finally, however, we return to the question posed at the beginning: Can we arrest Nietzsche? Or, as Tucholsky claims, can it be used to justify everything, attack everything? Let us briefly look at the strategies with which certain statements from Nietzsche's philosophy are undermined, or at least put into perspective, so that Nietzsche, thought to the extreme, could not be pinned down to a single passage that “means something as it stands there.”

Resolution strategies and objections

That the opposite of every thesis can actually be found That's what it's called. This is a strong claim, but it has the advantage that examples are easy to list. Whether these contrasts remain opposites when interpreted more precisely remains to be seen at this stage. But is there an opinion that is never contradicted if you understand it in the simplest way? Lo and behold, self-determined death, for example, suicide, to name just one example, enjoys unrestricted affirmation in Nietzsche. He contrasts it strongly and unequivocally with the mental and physical sickness he criticizes, which comes to an end in natural death. A counterthesis to this is sought in vain.

Some statements must be understood biographically in such a way that they can be practically subtracted from Nietzsche's philosophy. The old woman who gives Zarathustra the uncharming advice to bring a whip when men go to women is, for example, just a persiflage on Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth. No misogynous attitude could therefore be derived from this position. But even if this is true, a philosophy stands for itself, and we interpreters study the perspectives that arise from it, and not Nietzsche's psyche of any kind. Psychologization, which initially served as a strategy to create a more pleasing and well-rounded Nietzsche, leads, when applied consistently, to the levelling of his philosophy, as virtually every statement can be interpreted biographically and psychologically. But then you finally have to come to the conclusion that his entire work can only be regarded as a biography of thought, which is philosophically irrelevant because it applies to no one but the individual who wrote it.

The philosophical speaker can be broken down into countless experimental figures. Based on the justified objection to hasty interpretations that simply equate Zarathustra with Nietzsche, and the recognition that experimental figures such as the “great person” cannot easily be identified with Nietzsche, the practice of completely removing the ground from a coherent “speaker ego” has become established. Is this “I” really the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche or is there a philosophical type, an experimental figure or even a distorted image? Are there perhaps as many Nietzsche as I in his texts? Well, then we can turn our backs on any attempt at a Nietzsche interpretation that is even halfway coherent, because there is simply no Nietzschean philosophy that could be characterized on the basis of content. This strategy can certainly be applauded; it is delicate and clever. Any collection of Nietzsche can thus be shattered, as it is barely possible to get hold of him. But why should we dedicate time to a philosopher who has only tried out positions without considering their veracity? Starting from an exciting, dazzling ambiguity, Nietzsche's philosophy slips into arbitrariness that you can walk past with a shrug.

Certain statements are meant ironically. This is quite obvious, but it also requires interpretative reasons such as the presentation of several clues. And if she receives this, an irreconcilable contradiction does not necessarily have to arise. Nietzsche could, for example, pay tribute to the “sovereign individual.”2 meant ironically because he only equipped it with a single skill, namely to be able to promise. However, this “freedom” to commit to something came from the worst system of coercion — the severe corporal punishment of anyone who breaks his promises. Yes, the irony is that the sovereign individual, who brags about his freedom, has forgotten the dark, barbaric period from which it was rescued. And yet, for Nietzsche, it is freedom that unironically marks a new step in human development. The irony here therefore proves not to be an indissoluble contradiction, but as a metaperspective of the person who sees both — their dark background and their proud face.

And lastly, we have the subtle interpretation, which applies his own critique to terms that Nietzsche uses seemingly natural, understandable in everyday life. Is this what he is saying as truth? But hasn't he removed the basis of the concept of truth itself? He talks about a ranking of perspectives, but who ranks them? He says that nature, the world is immoral in itself — when he has already thrown all statements “about himself” to pieces?

Integrative power

And this is exactly where we should not stop and simply state succinctly that a certain contradictory character is an integral part of Nietzsche's philosophy, but try to relate the apparent and actual contradictions, the various interpretations, to one another and to weigh them. How much can our interpretation of Nietzsche's philosophy integrate, this could become a yardstick for evaluating it. However, we should become careful and suspicious of ourselves if a round, self-contained philosophy actually emerges in which you suddenly and in good old tradition claim that all contradictions prove to be only apparent when you only use a key to interpret them. At some point, the mere interpretation of Nietzschein comes to an end and it is our own arguments that wrestle with certain aphorisms. It is our own positions, tastes, perspectives and values that we see attacked by him and that we try to defend, not least with the strategies he has learned. We have arrived in the thicket of a philosophy with which, if we dare, we can wrestle with and perhaps even find a way out. The fact that this outcome leads us out into our freedom and not into the heart and mind of the philosopher only makes thinking the adventure that it “actually” is in Nietzsche's sense.

Literature

Tucholsky, Kurt: Miss Nietzsche (1932). In: Mary Gerold-Tucholsky & Fritz J. Raddatz (eds.): Collected works, Vol. 3. Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 994.

Footnotes

1: Tucholsky, Miss Nietzsche, P. 994.