Splendidly Isolated with a Stiff Upper Lip

Nietzsche and the Tragedy of Academic Outsiderhood

Splendidly Isolated with a Stiff Upper Lip

Nietzsche and the Tragedy of Academic Outsiderhood

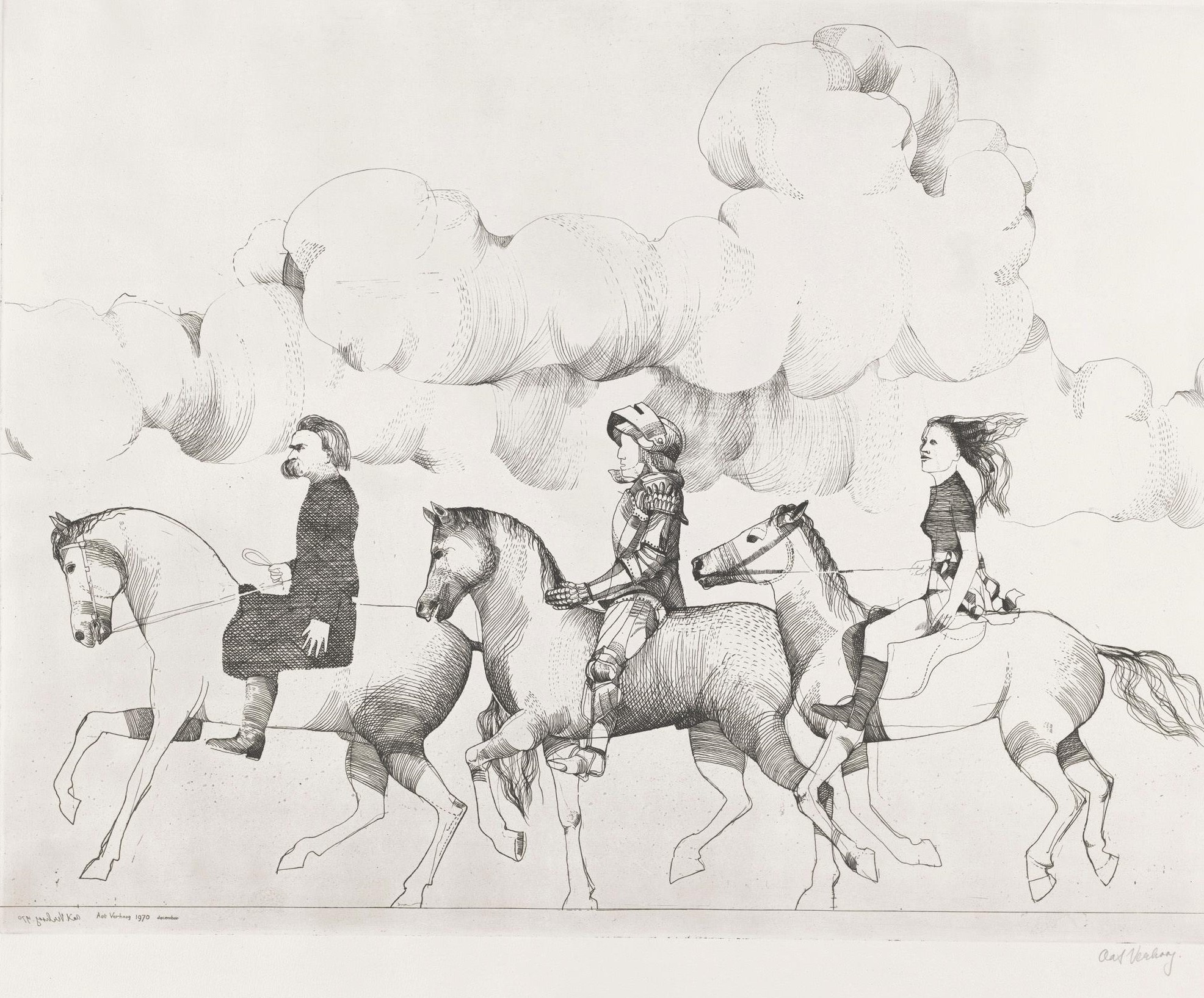

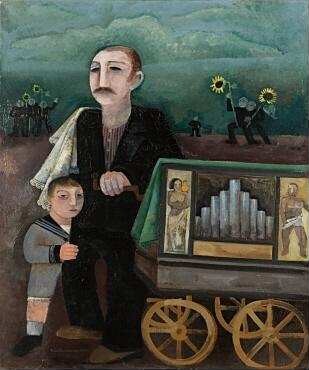

“Keep a stiff upper lip,” they say in England when you want to call on your interlocutor to persevere in the face of danger and to maintain an upright posture. Advice that is certainly often helpful. Such a stoic position must be sought all the more as an academic outsider who, on the one hand, sets himself apart from the scientific mainstream, but on the other hand is also dependent on his recognition. Nietzsche himself, but also many of his admirers, found himself in such a delicate situation. Based on several such outsider figures (in addition to Nietzsche himself, such as Julius Langbehn and Paul de Lagarde), Christian Saehrendt develops a typology of the (perhaps not always quite so) “brilliant isolation” of academic nonconformism.

I. Nietzsche, Lagarde, Langbehn

Who actually belongs to the reputable academic world? And who determines that? Negotiating and defining scientific-academic exclusivity is a permanent problem, because the nature of engagement with the “outside” also shapes academic activity internally. Friedrich Nietzsche knew how to sing a song about it, but other intellectuals of his time also lived and suffered in “brilliant isolation” because they were ostracized from academia as newcomers, unprofessional amateurs, amateurs or impostors.

The comfort and hope of the isolated was and is the fact that their peers succeed in achieving major journalistic successes on a case-by-case basis and attracting strong public attention — which in turn brings them envy and even deeper aversion from the academic sector. This is exemplified by Paul de Lagarde, Julius Langbehn and Oswald Spengler. In the period 1880 to 1930, these cultural critics and bestselling authors played a significant role in determining the humanities discourse in Germany, although they were all academic outsiders and socially isolated eccentrics. Langbehn and Spengler referred heavily to Nietzsche, who was regarded as a science critic and also an academic outsider of his time, and who in turn was impressed by the maverick Lagarde.

Nietzsche also fit perfectly into the pattern of the unsociable, “difficult” private scholar in character, who had neither strong family nor social ties and was largely avoided by academia. While Nietzsche only became famous posthumously, the intellectual outsiders Langbehn and Spengler were able to become both controversial and highly regarded stars of cultural life during their lifetime. In doing so, they surfed on the waves of Nietzsche reception. While Langbehn tried in vain to gain guardianship of the sick Nietzsche, Spengler became an important representative of the established Nietzsche community in the Weimar Republic1. In two biographical sketches, Lagarde is now described as a prototype of the scientific outsider, before Langbehn comes into view as a Nietzsche epigone. In this way, similarities and differences to Nietzsche's way of life become clear.

Paul de Lagarde alias Anton Böttcher (1827-1891) was one of the most famous cultural critics in the German Empire. His main work, published for the first time in 1878 German writings, combined moral criticism of education, culture and customs with extreme nationalism. The roots of his thinking were Protestantism and Prussian ethos, the basis of his writings was a deep cultural pessimism, presented in a “kind of whiny heroism. ”2 He was controversial among scientists because of his antiquated worldview and lack of methodological awareness. He had to wait fifteen years for a chair and in the meantime taught at schools until he received an appointment to the University of Göttingen in 1869. His quarrelsome was considered notorious. He was in correspondence with Richard Wagner, among others. Nietzsche was impressed by Lagarde's writings but also read them critically, while Lagarde showed no interest in Nietzsche.3 In the last decade of his life, Lagarde came closer to the anti-Semitic movement around Nietzsche's brother-in-law Bernhard Förster. In the post-war situation from 1919, a second wave of reception began. Lagarde could now serve as a convenient Nietzsche substitute for all those to whom Nietzsche's statements about the German Reich and Judaism seemed too complex and unpatriotic.4 With Nietzsche, he combined his high standards of himself and his enormous workload:

Of course, Lagarde lacked the philosopher's spirit of experimentation, and his outstanding character traits such as envy, avarice and resentment make us feel his inner hardening. He often carried the grudge against individual colleagues with him for years before he publicly exploded, and he relived long-ago insults over and over again. [...] In the fight against his own inner emptiness, which was expressed in massive exhaustion and exhaustion of life, he spoke of courage to himself in a loud voice [.] [...] Lagarde's fate shows how close psychological damage, targeted self-stylization and charismatic effect can be interrelated.5

Julius Langbehn (1851-1907) had studied various subjects in Kiel and Munich before receiving his doctorate at the age of 29 — an almost “biblical” doctoral age at the time. He then led an unsteady life with changing jobs and residences for about a decade. He was unable to gain a foothold in academia. In 1891, he demonstratively sent his doctoral certificate back to Alma Mater, the University of Munich. His anonymously written essay Rembrandt as an educator. From a German was his only, albeit resounding, literary success. The book spread pan-Germanic sense of mission and combined irrational scientific hate with global cultural missionary zeal. He deliberately had the title as an allusion to Nietzsche's third Untimely viewing, Schopenhauer as an educator, elected. Langbehn adopted ideas from young Nietzsche and integrated them into a German-national world view. He rejected later works by Nietzsche as “aberrations.” Soon after publication, Lagarde, Georg E. Hinzpeter, Wilhelm II's tutor, and even Nietzsche himself, were authors of rembrandt-Buch suspects his aphoristic, contrived style such as “a clumsy attempt to imitate Nietzsche's late prose”6 worked. As early as January 1890, Langbehn came out to Lagarde, whom he revered, as an author,7 before Langbehn's true authorship became generally known, and he received the nickname “the Rembrandt German”. The success of the book was an expression of the mystical expectations of the time, which called for prophets of all kinds, especially from the realm of art. The stylistic and intellectual deficiencies in the text had a beneficial effect under these circumstances: Chaos and absurdity could simulate depth and background, constant repetitions had a hypnotic effect, deviating sentence structure and punctuation suggested an individual “creative” expression, lack of arguments and footnotes corresponded to the writing “genius,” naming recognized artists and historical figures simulated reading and conferring authority. Many well-known reviewers wrote detailed and positive reviews. Langbehn was often seen as the heir of the silent Nietzsche. Langbehn even made an attempt to heal it in the winter of 1889/90. After he had earned his mother's trust, he accompanied Nietzsche on walks for weeks, talked to him, slandered his doctors and friends and finally even called for guardianship of the sick person.8 It was fatal that the spread of Langbehn's ideas coincided with the first notable wave of Nietzsche reception, meaning that both could appear as prophets of an individualistic art religion and Langbehn could even be regarded as the heir of the philosopher and guide through his ideas. Langbehn had brought Nietzsche “far more to the people than had been the case up to then”9, summarized Erich F. Podach as early as 1932.

II. Mechanics of Rejection: Academic Business in Conflict with Outsiders

Based on a number of formal criteria, it is easy to determine whether someone belongs to the established scientific community: academic degree and affiliation, publications in established journals and reputable publishers, presence at scientific conferences, on juries, as reviewers and on appointment committees.

This does not mean that the non-integrated person must not contribute ideas from outside to the company, but it will be much more difficult for him to be heard than someone who is already on the inside. In earlier times, when the fragmentation of disciplines had not yet progressed so far and many were doing science as private individuals, this was even easier.10

Negotiating and defining academic exclusivity is an ongoing process in academia. Dealing with outsiders, minority opinions and laypeople determines his internal climate and ability to innovate. When assessing outsider positions, insiders suffer from a fundamental problem: many researchers — in a positive sense — have a manic fixation, an unconditional will to solve a problem or find an explanation, or a highly focused flow that occurs during experiments and calculations. The psychological energy that flows into research can also involve tunnel vision and the neglect of social contacts and conventions. This sometimes manic or nerdy habit combines the reputable researcher with a psychologically impaired outsider: “However, the same incessant mental work can be observed in any paranoid and it is often difficult to distinguish a brilliant creative person from a jumble head. ”11 In addition, the scientist's working methods require constant refinement and perfection of theories once established, which can lead to a fixation on certain methods and results, which sometimes results in stubbornness that hinders progress in old age:

Recognized and powerful scientists who hold outdated ideas usually try in every way to slow down other scientists and throw clubs between their legs when they have embarked on a new path.12

Unfortunately, there is almost only one biological solution to this problem, as Nobel Prize winner Max Planck once stated:

A new scientific truth tends to assert itself not by convincing its opponents and declaring themselves to have been taught, but rather by gradually dying out its opponents and familiarizing the growing generation with the truth from the outset.13

The rejection of scientific outsiders by established researchers and officials is therefore often based on an “erroneous judgment on the part of the competent person,” who is unable to abstract from his acquired convictions and thus stubbornly insists on school opinion. Professional authorities tend to dismiss positions that contradict their theories as irrelevant or even unscientific. In this sense, they look for mistakes and signs of dubiousness and find what they are looking for in particular in formal or linguistic details, while disregarding the opponent's arguments and theoretical content:

The significance of such minor deficiencies becomes all the more the focus of attention when an idea comes from someone who is only slightly regarded, has little proof of qualification and is perhaps also distinctive in character, unadjusted, excessively aggressive and megalomaniac, or, on the contrary, all too modest and reserved. The scientist therefore allows himself to be misled by his own competence and antipathy and finally makes a negative verdict.14

Because a “crank” (= jumble, lateral thinker) or more elegant “maverick” (= outsider, but also “stray”, i.e. free)

Not part of the scientific corps, publications are difficult, the necessary amateurish presentation and aggressive tone justify a superficial analysis of his ideas and make them more likely to be rejected. What follows is a series of discriminations that make the victim even more aggressive, and the likelihood of being rejected and marginalized as a madman increases significantly.15

III. Typology of the scientific outsider

Endoheretics criticize the scientific community from within because they have a status within it, albeit disputed, while esoheretics approach the scientific community from outside and are generally completely rejected by it. In some cases, endoheretics who left the scientific community through retirement, expulsion or voluntary resignation turned into esoheretics. Nietzsche also falls into the latter category.

If heretics want to continue their research on their own and without the support of academic bureaucracy, this is only possible if private assets or non-university sponsors are available. Nietzsche lived on the pension granted to him by the University of Basel, Lagarde enabled the adoptive mother's inheritance to publish sixteen scientific papers and books in parallel with his teaching activities at schools.16 A small inheritance following the death of his mother had given Spengler the opportunity to give up his teaching activities and pursue his literary ambitions as a freelance writer.17 Langbehn, in turn, had powerful friends and sponsors such as Wilhelm von Bode in the background, who gave him the opportunity to appear as an author.

Ideally, the wealth is so large and the social status is so established that maximum independence from scientific institutions is possible. The English private scholar Henry Cavendish (1731-1810), one of the most important naturalists and richest scholars of his time, was the prototype of the financially independent, eccentric and often interdisciplinary, universalist “Gentleman Scholars” of the 19th and early 20th century. He owned a large library, carried out numerous experiments, but avoided contact with institutions and colleagues and had no interest in publishing his results. He was completely fixated on his studies, lived in isolation on his estate without any social ambitions.

But not all those rejected by the scientific community are as self-absorbed as Cavendish. Most thirst for scientific and social recognition. They are tempted to make themselves heard through self-financed and published publications or through paid advertisements. Some have created publishers, journals, series of editions or even encyclopedias specifically to publish their articles and theses. With the self-publishing platforms, YouTube channels, blogs and book-on-demand options of the Internet age, the opportunities for academic outsiders to present themselves seem to have grown significantly today. However, this in no way guarantees seriousness — on the contrary: self-published material is widely regarded as a flaw in the scientific community, while established publication sites and citation cartels continue to exist that keep scientific outsiders at bay.

The current peer review process, the review of research proposals and journalistic contributions by anonymous academic colleagues, also has a thoroughly disadvantageous effect on the innovative capacity and diversity of the scientific community, because they are often competitors of the applicant. It goes without saying that in this way and in the shadow of anonymity, it is easy for established scientists to sabotage and exclude outsiders and newcomers: “You can be sure that some of the most groundbreaking work would never have appeared in the past if it had been peer reviewed according to today's standards. ”18

Then as now, some of the rejected people lost themselves in parascientific communities and anti-science positions. Without corrective contacts with academic colleagues, they delve into absurd theories. Others are moving into areas of popular science. A few of them can celebrate major successes in the media and on the book market with populist or sensational theses — and then use the symbolic capital they have acquired in order to achieve a certain degree of recognition in academia. In many cases, those rejected by the scientific community were and are driven by the motivation to compensate for the rejection experienced as an insult or even to take revenge for it in a certain way. This explains the sometimes extremely radical content positions and the polemical aggressiveness of language, although this verbal radicalism may be regarded as a specific form of toxic masculinity, for example as a substitute for unexpressed physical aggression:

Spengler is the type of inhibited, lonely and socially isolated thinker who manages to make a monumental work in the midst of his depression. There is hardly a case where the current psychological compensation argument would be more plausible than here: The impotent, fearful and inhibited Grübler creates a vision of the world with bossy language that transcends everything and makes every personal contingency appear meaningless.19

Academic outsiders such as Lagarde and Nietzsche adepts such as Langbehn and Spengler were able to celebrate great successes in Germany more than a hundred years ago — they played a decisive role in shaping the cultural discourse of the time. But their intrinsic motivation, the core of their business model, was based on managing resentment. As poisonous outsiders, they popularized cultural pessimism, anti-Semitism, and hostility to science. It was also a fatal long-term effect of Langbehn's and Spengler's writings that they pushed Nietzsche into the far-right field of discourse and thus prepared for his misuse by fascism.

In the universe of academic idiots and scientific outsiders, Nietzsche also shone as a lonely star. After moving to Basel, Nietzsche became stateless in 1869. From the winter semester of 1875/76, he is also unemployed; the University of Basel gave him leave of absence for health reasons. He had already read through the publication The birth of tragedy Isolated in the philological community, where his approach was considered too artistic. After leaving the circle of Wagner followers and following the final departure from academic teaching due to health reasons and retirement by the University of Basel, Nietzsche led an independent life as an academic outsider and free spirit. He commutes between Italy, France, Switzerland and Saxony and lives quite sparingly in order to be able to finance journalistic projects with his pension: “The ideal of life that, as a young professor, he had praised in his Basel lectures 'On the future of our educational institutions, 'of being able to live alone and in dignified isolation now seems to be fulfilled. '”20

He travels and publishes extensively, but remains without much public response; only a few friends and insiders know his writings. Gentleman scholar Nietzsche endures his Splendid insulation with Stiff Upperlip, and takes comfort in the conviction that you won't be understood until 100 or 200 years from now.21

Article image: Photo of a Swiss mountain landscape by Christian Sährendt

sources

By Trocchio, Federico: Newton's suitcase. Brilliant outsiders who embarrassed science. Frankfurt 1998.

Janz, Curt Paul: Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. III. Munich 1979.

Felken, Detlef: Oswald Spengler. Conservative thinker between empire and dictatorship. Munich 1988.

Gerhardt, Volker: Friedrich Nietzsche. Munich 1995.

Planck, Max: Scientific self-biography. Leipzig 1948.

Podach, Erich F.: Design around Nietzsche. With unpublished documents on the history of his life and work. Weimar 1932.

Sieferle, Rolf Peter: The Conservative Revolution. Five biographical sketches. Frankfurt am Main 1995.

Victory, Ulrich: Germany's prophet. Paul de Lagarde and the origins of modern anti-Semitism. Munich 2007.

Summer, Andreas Urs: Between agitation, religious advocacy and “high politics.” Paul de Lagarde and Friedrich Nietzsche. In: Nietzsche research Vol. 4 (1998), pp. 169—194.

Stern, Fritz: Cultural pessimism as a political threat. Bern 1963.

Vuketits, Franz M.: Outsiders in science. Pioneers — guideposts — reformers. Heidelberg 2015.

footnotes

1: See in detail my article about Spengler on this blog (link).

2: Fritz Stern, Cultural pessimism as a political threat, P. 52.

3: Cf. Ulrich Sieg, Germany's prophet, p. 168 ff.

4: Cf. Andreas Urs Sommer, Between agitation, religious foundation and “high politics”.

5: Victory, Germany's prophet, PP. 355—358.

6: star, cultural pessimism, P. 148.

7: Cf. victory, Germany's prophet, P. 299.

8: For this episode, see Curt Paul Janz, Friedrich Nietzsche, pp. 96-113 and Erich F. Podach, Figures around Nietzsche, P. 177-199.

9: Ibid., p. 197.

10: Vuketits, Outsiders in science, P. 35.

11: Federico Di Trocchio, Newton's suitcase, P. 22.

12: Ibid., p. 244.

13: Max Planck, Scientific self-biography, P. 22.

14: Di Trocchio, Newton's suitcase, P. 100.

15: Ibid., p. 23.

16: Cf. victory, Germany's prophet, P. 73.

17: Cf. Detlef Felken, Oswald Spengler, p. 25 ff.

18: Vuketits, Outsiders in science, p. 36 f.

19: Rolf Peter Sieferle, The Conservative Revolution, P. 106.

20: Volker Gerhardt, Friedrich Nietzsche, p. 48. Cf. About the future of our educational institutions, 5th presentation.

21: Cf. Gerhardt, Friedrich Nietzsche, P. 57.