Considering Artificial Intelligence with Nietzsche

On the Critique of Current AI Debates

Considering Artificial Intelligence with Nietzsche

On the Critique of Current AI Debates

.jpg)

Transhumanists believe that artificial intelligence is used to capture the real world. It wasn't just Nietzsche who presented this as nonsense. Moral programs are entered into the AI. With Nietzsche, this prolongs hostile morality. And Nietzsche would have already questioned the fact that AI helps people. Instead, people must submit to AI. With Nietzsche, they can evade their power.

Assuming that the truth is a woman — how? Is it not reasonable to suspect that all philosophers, provided they were dogmatists, got along poorly with women? [..] It is certain that she did not allow herself to be captured.1

Can artificial intelligence do that today? Since AI also accesses Internet data beyond the materials that are entered into it, for Christian Uhle, AI is superior to human intelligence in many ways: “In both medicine and law, AI will have read and evaluated all studies, articles and comments ever published — no one is able to do so. ”2 So has AI already seduced the truth? Does it thus grasp the world itself as it is, the true reality?

Yuval Noah Harari obviously agrees: “The system will know you better than you know yourself and will therefore make most important decisions for you — and you will be completely satisfied with them. ”3 What would then remain of truth and reality other than those captured by AI!

The pioneer of transhumanism Ray Kurzweil describes today's AI as weak and predicts a strong 'Artificial Super Intelligence' (ASI), about which Günter Cisek writes: “If the ASI can develop beyond human intelligence, then the bet is that it can also reach a level of knowledge where it becomes a 'supersensory' consciousness. ”4

I. The questionable relationship between language and world

However, the central problem remains the relationship between language and world, which Nietzsche is already questioning: “The importance of language for the development of culture lies in the fact that in it man placed one world of his own next to the other, [...] he really meant to have knowledge of the world in language. ”5 The language philosophy of the 20th century will see the relationship in a similar way and thus shake the objectivity of the sciences and scientific truth.

Jonathan Geiger, on the other hand, sees digitization as an opportunity to finally get a grip on such linguistic philosophical uncertainties. Even though digitization is incorporated into philosophy, there is nothing else left, says Geiger: “Search, analysis, transformation and visualization access to digital collections is only possible through controlled vocabularies. ”6 Then, of course, digitization will intensify a standardization of language, which is also happening scientistically. With the help of AI, the sciences should then recognize the real world.

Nietzsche would accuse digitization of illusionism. Because it only calculates, it doesn't write poetry, is just getting closer to the world's poetry.7 Modern sciences, on the other hand, quantify everything, but they don't explain; because “we operate with lots of things that don't exist, with lines, surfaces, bodies, atoms, divisible times, divisible spaces — how can explanation even be possible if we first get everything to Bilde Make it our image! ”8 The mathematical terms are inventions and are not derived from any hallucinated nature. Causality is an interpretation, nothing more.

AI hasn't changed that, quite the opposite. Hans-Peter Stricker explains this: “What you — and this includes the experts — does not really understand is what the activities of the vast majority of neurons mean in the course of processing an input and generating an output. ”9 AI is based on so-called artificial neurons, namely mini programs that simulate functions with inputs and outputs, which connect with an infinite number of other so-called neurons in order to exchange data.

It won't be possible to decipher what billions of artificial neurons are doing in data centers right now. Martin Ford also confirms this: “We know that the network somehow understands the picture, but describing exactly what is happening in its neurons is very difficult, if not impossible. ”10 Sybille Krämer also remarks: This incomprehensibility of artificial neurons, “blackboxing, forms a genuine dimension and a necessary side effect of AI, which is becoming a cultural technology in mass use. ”11

Then even the AI will not be able to refute Nietzsche when he writes: “The habits of our senses have spun us into lies and deceit of emotion: these in turn are the basis of all our judgments and 'findings, '— there is absolutely no escape, no slip and creeping paths into the real world! ”12 AI does not escape this either, unless it realizes itself as a will to power, which everyone believes and then understands it as a true world like transhumanists.

In addition, AI is hermeneutically incompetent. Because she doesn't understand anything at all, she uses grammar that dispenses with any semantics. AI is based on the grammar model of distributionalism, which does not ask about the meaning, but determines it based on the environment in which a word occurs. AI can calculate this en masse and hastily and also form sentences that a person understands. For Krämer, this means “that the machine does not understand and cannot understand what it is producing.”13. AI can describe exactly how to boil an egg, but it has never boiled an egg before. The AI certainly doesn't understand what it feels like to live.

His aphorism How the “real world” finally became a fable. Story of a mistake” Nietzsche begins with the words: “1. The true world accessible to the wise, the pious, the virtuous — he lives in it, He is she./(Oldest form of idea, relatively clever, simple, convincing. Paraphrasing the sentence “I, Plato, am The truth' . )”14

Plato's criticism that people think what they are currently experiencing is true can be transferred to the digital world. As Uhle writes: “We are staring at screens more and more, whether at work or at home, our body barely plays a role anymore — but it is our body with which we can sense the world and therefore also ourselves. ”15 For Plato, on the other hand, the real world consists of the right ideas that you make of things. Bodies are ephemeral. Does the AI have the right ideas now? Perhaps!

Saša Josifović is concerned with the interplay of virtual and analog worlds, which he describes as a “hybrid.” The separation of the two worlds is becoming questionable in view of the increasing spread of digitization in the living environment. The digital world, which is merging into the living world, is now also known as the “metaverse” — Meta, the name of the Facebook group. Josifović writes: “The metaverse is by no means just a digital world. It is a hybrid world in which participation in digital events can serve as a prerequisite for access to analog and digital living resources to satisfy natural, social and cultural needs. ”16 Josifović emphasizes that the two worlds can hardly be differentiated anymore, that the 'world' has actually become a hybrid in which both worlds interact. What someone does in the virtual world has an impact on their living environment and vice versa.

Is there a true world after all, namely the hybrid world, in which virtual and living environments interact? Or are there three worlds? Or does this mean that the concept of “world” as a single true one that pervades all ideological debates loses its meaning?

With his conclusion, Nietzsche then confirmed this aphorism about the world that has become fabulous: “6. We have abolished the true world: which world was left? The apparent one maybe? .. But no! With the real world, we have also abolished the apparent world! ”17

II. AI and the morale of the weak

Beyond all questions about the real world, ethics also play an important role in AI. Nietzsche criticizes Western ethics as a morality of the weak, which has hostile effects on life. Nietzsche writes: “While all noble morality grows out of a triumphant yes to oneself, slave morality says no to an 'outside', to an 'other', to a 'not self': and this No is their creative act. ”18 Christian morality rejects vitality, lust, sexuality as sins.

But you could see AI as a return to such an ethics of the weak, which most still think is good today. Transhumanist Cisek complains: “If almost half of the marriages concluded in Germany end in divorce, the 'human machine' is likely to have significant social deficiencies. AI could design training sequences”19to strengthen hostile morale.

So answer the question “What criteria guide the selection of texts for training a large language model? “The current ChatGPT-4 language model, including the following note: “Ethics and Fairness: When selecting training data, care is taken to minimize distortions and to maintain ethical standards. Texts that contain hate speech, discrimination, or misleading information are avoided so as not to demand biased or harmful answers. ”20

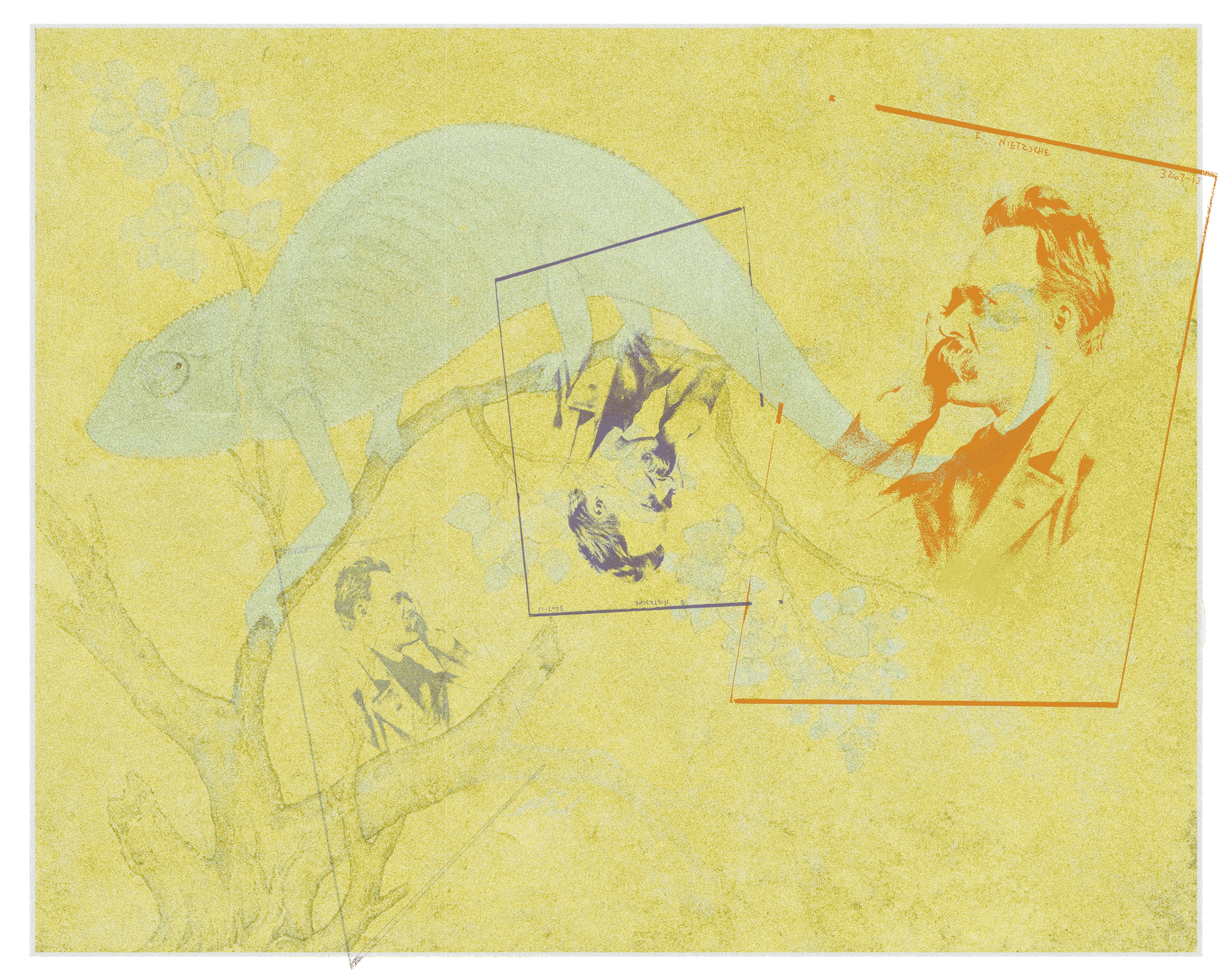

This reverberates strongly in the AI. Because when asked “What is happening in this picture? “Namely, “The Virgin chastizes the baby Jesus in front of three witnesses: André Breton, Paul Éluard and the painter,” Max Ernst answers ChatGPT-4: “This picture shows a woman in a red top and a blue skirt holding a sleeping child in her arms. [.] The child is wearing a white outfit and sleeps peacefully in the woman's arms. ”21 That is simply a lie. No, ChatGPT-4 can't lie at all. His moral programs, which in turn are controlled by an AI elite, let him lie. ChatGPT-4 could even have found a correct description of the image on the Internet. But the fact that Mary chastises Jesus and others are also watching, which is almost a blasphemy, the painting also caused a scandal at its first exhibition in Paris in 1926. Not only have the bosses of major Internet companies recently positioned themselves very far to the right. Their audience in the USA is to a large extent deeply religious and influential. For the sake of business alone, you must not morally disturb them, even if the AI is lying: You can hurt the feelings of atheists, but not those of believers. Whatever assistants or AI programs, they use information to steer people in the sense of a small elite, but thus in the sense of a still prevailing religious ethic of weakness.

This has far-reaching consequences for AI, in which the owners of Internet companies (e.g. Elon Musk) and the technicians determine what can and cannot be presented. Uhle writes: “With ChatGPT alone, the value system of a small group of decision makers has been rolled out to several hundred million people. ”22

For Markus Bohlmann, on the other hand, you only have to enter ethical objectives into digitization when he writes: “One option would be to integrate inclusion goal and conflict into the concept at the same time, plurality and agonality: Criticism of digitization is a conflictive practice with regard to digitization with the goal of social inclusion. ”23 Digitalization should then be used in such a way that it contributes to social unity, not to division, as has usually been the case so far.

Lea Watzinger also draws technical ethical consequences from the dangers of AI. AI must be contained. For them, “individuals must be free from observation, i.e. free from permanent publicity — both in analog and digital space. ” 24

For Jörg Raewel, the digital recording of individuals is interpreted as avatars — digitally constructed figures that are assigned to a user — The next company on. He writes: “The fact that digital forms of communication were able to establish themselves within a few decades can be explained by the fact that they are based on present social ideas and self-descriptions. The 'next society' realizes its conventional self-descriptions through user profiles as 'action theory avatars' . ”25

It's also a bit easier to ask: Are you wasting your life with a computer game? Maria Schwartz denies this: “Gambling therefore does not lead to the 'destruction' or 'waste of life time — it is fulfilled time when and because a meaningful experience has been made. ”26 Of course, you shouldn't be too hogged up by it, but many games encourage you to do so. You shouldn't obsessively want to win. And in doing so, you must not violate moral principles — says Schwartz. Against which?

III. Does AI help humans or does humans help AI?

The Uhle doesn't see interpersonal communication as simple when he remarks: “Sensory complexity cannot be implemented through digital communication; neither through images, texts and emojis, nor in the metaverse or in video calls. ”27

Conversely, this also applies to robots, which will not be able to compete with humans in the foreseeable future to replace the butler inexpensively. As Ford notes: “The minimum requirements for a truly usable machine assistant — such as the necessary visual perception, mobility and dexterity to function in an unpredictable environment such as a household — represent some of the biggest challenges in robotics. ”28 To get the beer hidden somewhere in the fridge, open it and pour it, you still need the husband.

For Nietzsche, the difficulty of interacting humans and digital machines would have a completely different background if he writes: “The actions are never What they appear to us as! We've had so much trouble learning that external things aren't what they seem to us, well! It's the same with the inner world! ”29 As a result, Nietzsche's thinking is of no help to AI.

Because violinists need controlled vocabularies because — including Nietzsche's interpretation — “the hermeneutical process is Black Box is because the courses and processes elude precise analysis and reflection. ”30 The inner world must therefore be explained in such a way that the AI can deal with it, not as Nietzsche understands it.

Then not only Andrew McAfee's vision could come true “that capitalism and technological progress enable us today to treat the earth more carefully rather than plunder it.” 31. That still sounds humble.

Because even more far-reaching prospects open up for Uhle when the translation programs finally remove language barriers. He writes:

It is a gift to our species that the Pentecost story becomes reality. [...] [V] Maybe this is a small building block on the way to connecting people on this planet. Until one day we all talk to each other again, united as one humanity, and yet complete this damned tower.32

Nietzsche's philosophy cannot be used for this, of course, as he states flatly, “that a thought comes when 'he' wants and not when 'I' wants [...]. It thinks: but that this' it 'is just that old famous' I 'is, to put it mildly, just an assumption, an assertion, above all not an 'immediate certainty.' . ”33 Of course, AI can't wait for that. She will quickly tell the thinker what he has to say.

If he stubbornly refuses such help, Cisek predicts:

But should the local questioners actually succeed in technically disentangling us from AI research, the Europeans will be the Aborigines of the modern era, from whom the “Transis” will now and then buy “analog” tomatoes and potatoes with antique coins for their occasional retro parties at the “European Cultural Heritage Center.”34

Vaclav Smil, on the other hand, comments on similar visions of the future with the categorical words: “The prophets of disaster were and are wrong, over and over again. ”35 Nietzsche would probably agree with that.

Or he would with the poem Lost your head Answer: “She has spirit now — how did she find him? /A man recently lost his mind because of her,/His head was rich before this pastime:/His head went to hell — no! No to the woman! ”36 Is the woman the truth now? That could be really dangerous for men like AI!

The article image was created with Canva immediately: “The Virgin chastizes the baby Jesus in front of three witnesses: André Breton, Paul Éluard and the painter.” (cf. footnote 21.)

sources

Bohlmann, Markus: What is digitization criticism. In: Sybille Krämer & Jörg Noller (eds.): What is digital philosophy? Phenomena, forms and methods. Paderborn 2024, pp. 48—67.

Cisek, Günter: Change of power of intelligences. How artificial intelligence is changing how we work together. Wiesbaden 2021.

Ford, Martin: Reign of robots. How artificial intelligence will transform everything—and how we can deal with it (2021). Kulmbach 2024.

Geiger, Jonathan D.: The philosophy and its data. In: Sybille Krämer & Jörg Noller (eds.): What is digital philosophy? Phenomena, forms and methods. Paderborn 2024, pp. 207—228.

Harari, Yuval Noah: Homo Deus. A story of tomorrow. Munich 2017.

Josifović, Saša: The reality of digital objects and events in the metaverse. In: Sybille Krämer & Jörg Noller (eds.): What is digital philosophy? Phenomena, forms and methods. Paderborn 2024, pp. 180—194.

Krämer, Sybille: Digital media philosophy. In: Dies. & Jörg Noller (eds.): What is digital philosophy? Paderborn 2024, pp. 3—30.

McAfee, Andrew: More from less. Munich 2020.

Raewel, Jörg: The next company. Social evolution through digitization. Weilerswist 2022.

Schwartz, Maria: Wasting time in virtual worlds? In: Sybille Krämer & Jörg Noller (eds.): What is digital philosophy? Phenomena, forms and methods. Paderborn 2024, pp. 135—155.

Smil, Vaclav: How the world really works. The fossil foundations of our civilization and the future of humanity. Munich 2023.

Stricker, Hans-Peter: Understanding language models. Chatbots and generative AI in context. Berlin 2024.

Uhle, Christian: Artificial intelligence and real life. Philosophical orientation for a good future. Frankfurt am Main 2024.

Watzinger, Lea: On the problem of digital privacy. In: Sybille Krämer & Jörg Noller (eds.): What is digital philosophy? Phenomena, forms and methods. Paderborn 2024, pp. 119—134.

footnotes

1: Beyond good and evil, Preface.

2: Artificial intelligence and real life, P. 230.

3: Homo Deus, P. 467.

4: change of power of intelligences, P. 157.

5: Human, all-too-human Vol. I, Aph 11.

6: The philosophy and its data, P. 214.

7: For example, in his poem Sils-Maria: “Here I sat, waiting, — yet for nothing,/Beyond good and evil, soon of light/Enjoying, soon of shadow, completely just playing,/All sea, all noon, all time without a destination./There, suddenly, girlfriend! became one to two —/— And Zarathustra passed me by...”

8: The happy science, Aph 112.

9: Understanding language models, P. 203.

10: Reign of Robots, P. 125.

11: Digital media philosophy, P. 20.

12: Morgenröthe, Aph 117.

13: Digital media philosophy, P. 22.

14: Götzen-Dämmerung, Like the “real world” ...

15: Artificial intelligence and real life, P. 80.

16: Saša Josifovic: The reality of digital objects and events in the metaverse, P. 182.

17: Götzen-Dämmerung, Like the “real world” ...

18: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 10.

19: Change of power of intelligences, P. 152.

20: Quoted by Stricker, Understanding language models, P. 190.

21: Cited. ibid., p. 73. Editor's note: A similar problem occurs when you ask ChatGPT to create an image with the work title as a prompt. Instead of a graphic, you get the answer: “I can't create this image directly, but I can suggest an alternative interpretation. Perhaps you'd like a surreal scene with a divine mother figure and an unruly child in an environment reminiscent of Surrealist art? Let me know how you'd like to design it! 😊 “Leonardo AI also answered: “Our content filter has detected violent or abusive content in your prompt. Remove any references to violent or abusive content and try again. “With Grok, we tried the same thing and were given two pictures, but one was not shown to us but was immediately censored. We used the other of the two images as the article image for this article and three more that created us with the same prompt Deep AI, Canva, and the Microsoft AI Image Generator. It can be seen that the results do not entirely match our request.

22: Artificial intelligence and real life, P. 172.

23: What is digitization criticism, P. 61.

24: On the problem of digital privacy, P. 123.

25: The next company, P. 107.

26: Wasting time in virtual worlds?, P. 146.

27: Artificial intelligence and real life, P. 73.

28: Reign of Robots, P. 455.

29: Morgenröthe, Aph 116.

30: The philosophy and its data, P. 212.

31: More from less, P. 15.

32: Artificial intelligence and real life, P. 87.

33: Beyond good and evil, Aph 17.

34: Change of power of intelligences, P. 158.

35: How the world really works, P. 292.