Übermensch Hustling

Nietzsche Between Silicon Valley and New Right

Übermensch Hustling

Nietzsche Between Silicon Valley and New Right

This essay, which we awarded first place in this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing (link), examines Nietzsche's question of the “barbarians” in a contemporary context and analyses how his philosophy is being politically exploited today. Against this background, the text shows how hustle culture, platform capitalism and neo-reactionary ideologies have been economizing the ”will to power“ and have become a new form of subtle barbarism: an internal decomposition of cultural depth through market logic, technocratic myths, and performative nihilism. Nietzsche's thinking, however, can be used precisely to describe these tendencies in their genealogy, to unmask their immanent nihilism, and to present an (over-)humane alternative to them.

“[W]here are the barbarians of the 20th century? ”1

This question from a fragment of Nietzsche's estate still provokes today: Who are the current forces that challenge the existing order — and not out of a desire to destroy, but as an answer to a culture that is increasingly exhausted in resignation and market logic? Who are they barbarians of our time? This essay takes Nietzsche's question as a starting point for a contemporary analysis: Who has anything to oppose the progressive nihilism of our time — and what is at stake when philosophy becomes a tool of political mythology? In order to grasp the scope of this question, it is first necessary to analyse the different interpretations of Nietzsche in political thought of the 20th and 21st century.

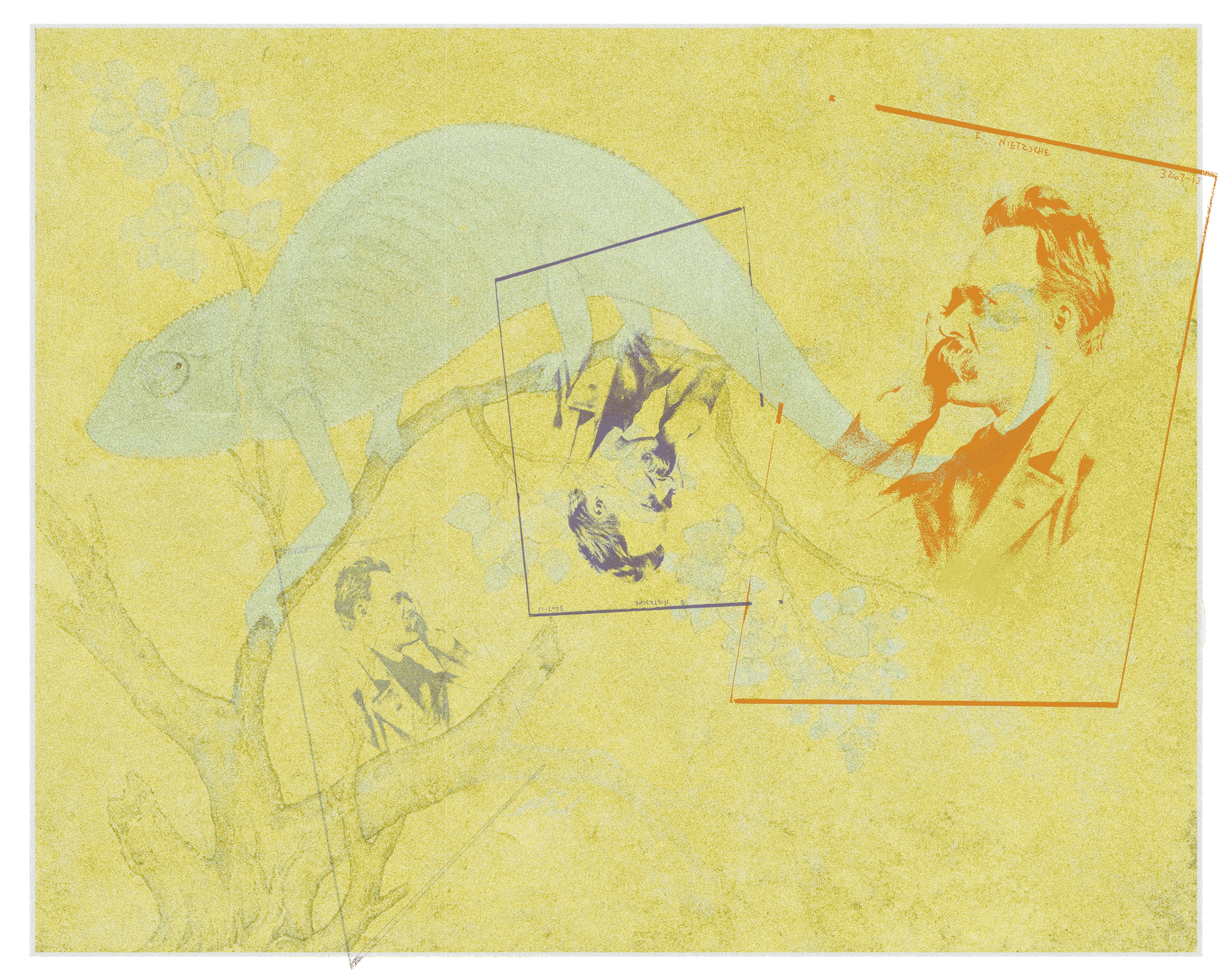

I. Power Mythology vs. Criticism

A clear difference between right-wing and left-wing Nietzsche reception lies in the way his texts are read and understood. Representatives of the New Right tend to take Nietzsche “at his word” and thus interpret it affirmatively. Terms such as”superman“or the”The will to power“are understood here as guiding principles for politics that are intended to justify hierarchy, elitist thinking and a fundamental rejection of egalitarianism. Here Nietzsche appears as a teaching prophet of a new aristocratic order. The appropriation of Nietzsche by right-wing movements represents a continuity and is exemplified by the collection of texts published posthumously by Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche The will to power Understand: Although never authorized by Friedrich Nietzsche himself, it became a reference text for an affirmative right Nietzsche reception — even under National Socialism, Nietzsche was misused as a supposed pioneer of a heroic, ethnic view of the world — even though he himself condemned anti-Semitism, nationalism and all authoritarian thinking. Martin Heidegger therefore initially relied on the falsified edition and reduced Nietzsche to a”Completion of metaphysics“— thus emptied his existential and genealogical radicality.2 In the New Right, from Alain de Benoist to Götz Kubitschek, Nietzsche continues to be stylized as a projection surface of post-liberal elitianism, while his critique of power, morality and resentment is deliberately reinterpreted or simply ignored. This is how an instrumental rather than philosophical reception takes place: pseudo-intellectually operating, ideologically inflated — and is thus at odds with every serious and dialectical, i.e. differentiated and reflecting rather than denying, Nietzsche's internal paradoxes of Nietzsche's work. It is also striking how the right-wing reception of Nietzsche is sometimes combined with neoliberal and libertarian views of the world: Is Nietzsche literally called the prophet of”Willens zur Macht“and read as a critic of egalitarian morality, based on this, a legitimation of unbridled competition and social hierarchy can be derived. The success of the strong — achieved in economic terms, for example by avoiding taxes — is no longer just an economic result, but is increased with the concept of morality: It appears as an expression of natural superiority. An originally cultural-critical stance thus tilts into a neoliberal ideology in which the market as a natural arena of”Supermen“is understood. In this way — paradoxically — morality itself becomes an instrument of domination. Opposite this is a (left-wing) Nietzsche reception, which reveals and criticizes precisely these mechanisms. Instead of reading Nietzsche as a pioneer of a new elite, she uses his thoughts genealogically to show how morality and discourse are misused to stabilize interests of power and profit. This is how the”The will to power“not affirmatively glorified — instead, it is analysed as what drives social norms, institutions and ideologies. Nietzsche's philosophy thus becomes a tool to visualize (“unmask”) rule as a culturally generated, not “natural” phenomenon — and thus to open up spaces for emancipation, solidarity and criticism.

II. Hustling in the Platform World

A literal Nietzsche reading, in which the”The will to power“and the success of the strong is morally transfigured, finds a contemporary equivalent in the”Hustle Culture“, which is being promoted en masse on social media platforms.3 Permanent self-exploitation — the Hustle —, optimization, self-marketing is regarded here as a sign of strength, of drive and, depending on the presentation, almost tips over into a heroic superhumanity. This Hustle Culture Based on Max Weber's analysis of the Protestant work ethic, can also be secularized doctrine of salvation Understand: Salvation is replaced by achievement and productivity thus becomes a moral duty.4 This ideology portrays work and performance pressure as an individual virtue, but deliberately conceals how much it supports existing power relations and ownership conditions at the same time: Because the platforms on which this cult is disseminated — whether on TikTok, Instagram or X (formerly Twitter) — belong to multi-billion dollar tech companies that themselves operate according to the logic of Willens zur Macht act and, by the way, make unimaginable profits from attention, data and unpaid work. Here, left-wing Nietzsche reception reveals the core of the problem: That morality and discourses — and also “self-realization” per se — are being exploited to legitimize platform capitalism and digital feudalism. While a few corporations receive the lion's share of the profits, it is suggested to individuals that they can Hustle for Supermen become — an illusion that cements the status quo instead of questioning it.

Against this background, the question posed at the outset appears as to who the”barbarians“in Nietzsche's sense today, in a new light: the right, often literal reception of Nietzsche interprets the”barbarians“often as a heroic elite who, with their will to power, will overthrow society in order to be able to establish new hierarchies; as”natural“Leaders in the age of decadent crowds. But if you look closely at the current reality of hustle culture, platform capitalism and digital feudalism, there is a clear turn of events: Now the very corporations and platforms appear that are the cults of absolute success, limitless self-optimization and Supermen promote as the actual barbarians; not in a romantic, heroic sense, but as destructive forces that destroy everything underground, everything fragile, everything humane in order to maximize profit. As a result, the mass of self-exploiters, who endlessly produce content on social media platforms and market themselves, are also becoming part of a new barbarism: not because they are the ones who brutally rule, but because they involuntarily reproduce the logic of the stronger and thus sacrifice cultural depth, critical reflection and solidarity. This shows how barbarism today means not only brute force, but also the cold, systematic eradication of difference, of real thinking: In other words, from what culture really means. Die barbarians From today, therefore, they do not (only) destroy from outside, but also act subtly from within when they normalize the rule of platforms and the myth of superman as a self-optimized entrepreneur. The so-called “hustle culture” is not a marginal cultural phenomenon, but an expression of a deeper ideology that also works in the spheres of tech CEOs and their discursive theoretical leaders. Where once Religion, morality and philosophy offered normative orientations, today an (avoidably) depoliticized aesthetic of success takes their place — fed by a technocratically oriented The will to power, who, as Adorno and Horkheimer would warn5 It no longer serves the purpose of enlightenment, but produces its dialectical opposite: myth in the mask of progress. This shift paves the way for trends such as the “neo-reactionary movement,” often abbreviated “NRx” — also known as “Dark Enlightenment” — which are based explicitly on Nietzsche, but in doing so shed all dialectical, historical-critical depth. NRx consistently puts this cult of success, which Hustle Culture stages emotionally on platforms, to the end: as a possibility of inhumanity, as a cybernetic reorganization of rule according to a market economy standard. The “theory” of NRx is based on pseudo-scientific concepts such as”Human Biodiversity”6 — an ethic of the stronger, based on racial ideological fallacies — or a right-wing libertarian understanding of the state as a corporate structure. In doing so, their representatives always refrain from contextualization, historical awareness, or moral reflection. The Dark Enlightenment performs nihilism where Nietzsche wanted to overcome it. Her followers cultivate the gesture of radicalism — but remain stuck in the pose, involuntarily funny. Your barbarian is a caricature: a cybernetic reactionary with a provocative social media profile, not a creative spirit. Anyone who takes the question of the barbarian seriously will have to evade this appropriation of Nietzsche: Are the true barbarians not the ones who deny cultural cynicism? (New) right-wing actors like to present themselves as the”stronger type“, which Nietzsche speaks of in the estate fragment quoted at the beginning: as those who could put an end to the “cosmopolitan chaos of affect and intelligence.” But their revolt is ultimately not aimed at new values (or even: morally based), but at the reactivation of old fantasies of order: authority, hierarchy — in the form of technological rule. They preach disenchantment but conjure up their own myths: the market as a machine of revelation, the code as proof of God, eternal life in the cloud, the CEO as sovereign. In this world, Nietzsche is not read, but utilises: as a (pseudo) aesthetic cipher of a The will to power.

III. A Left-Nietzschean Alternative?

The decisive difference here lies in the fact that Nietzsche's barbarians did not think as functionaries of a new system, but as existentially disruptors: as those who become capable and active of creation within and within themselves through radical work. In Nietzsche, it is the individual who counts, not the elite. “Superman is the meaning of the earth”7, Zarathustra calls out to “everyone and none” — and this superman is not created through technological progress: He is not a cyborg, not a post-human subject, but is capable of revaluation, transformation, artistic self-creation. So the question remains: Are the new tech CEOs really the barbarians Nietzsche was hoping for — or a post-ironic simulation of the same idea? Perhaps they are the caricature of the change that Nietzsche called for: forgetful of the future, strategically arrogant, metaphysically hollow. And yet it is precisely this radical, existential seriousness that is caricatured in the aesthetics of the New Right: What is there as barbarism staged — in podcasts, supposed guerrilla aesthetics and pseudo-intellectual tech-bro attitude — is not an answer to nihilism, but its performative implementation. The New Right and its sympathizers hide behind this mask of “(post) ironic barbarians“: a pose that at the same time rises above seriousness and yet asserts itself as an avant-garde. Her protagonists act like characters from a Kantian parody: They act As if they follow a transcendental maxim only to distance themselves from the character of their own actions in the next moment.8 Kant would not diagnose freedom here, much more heteronomy through cynicism, a moral mistake that Freud would describe as “rationalization”: A cultural superego is simulated, while the will to nihilism has long since reigned.9 Nietzsche would be the harshest critic of this game, because his idea of the barbarian sets a radical “psychological [] nudity” 10 ahead, an existential openness that is not fed by cynical laughter, but by the risk of self-creation. When Nietzsche writes that the”barbarians““the greatest harshness against yourself must be able” (ibid.), then he does not mean cold technocratism, but a critical examination of one's own entanglement in what you criticize yourself. The barbarian It is therefore not the one who ridicules existing orders, but the one who is able, after the collapse, to create a new order that is no longer based on the resentments of the old ones. The New Right, on the other hand, replaces design with the economy of affect: It imitates depth without suffering it. Your”barbarians“are actors in an ideological theatre. The result is not a new myth, but a nihilistic cultural struggle that is intoxicated by the rubble of modernity without thinking of or even building anything new.

The actual question of the “barbarian” thus ultimately leads back to a paradoxical movement: barely asked, this question reveals one's own longing for the outside that does not exist — a symptom of that decadence that one hopes to overcome (and which Nietzsche himself has strongly criticized). This essay here too remains — in addition to an analysis of the status quo — itself part of an order that he questions and continues at the same time. The barbarism of our present day is therefore not the raw outside, but the subtle inside: the total exhaustion that turns every revolt into pose; the boredom of a world in which “being against” also becomes an ornament of the market. The new barbarians do not appear as heroic figures, but as algorithms — which structure our attention while we are still Believe to vote. They are machines of power that mark themselves as progress and liquidate the actual culture in that process. In a state of entropy, becoming remains possible — just think of Deleuze's concept of becoming11: not as a harmonious solution, but as a risky affirmation of difference. Chaos is not only disintegration, but also a condition for creation, a movement within dissolution: the risk of acting without guarantee as an imperative. In the end, neither remains barbarian Still a humanist — just the question of whether it is possible to act differently in the awareness of one's own entanglement without knowing what this “different” can mean.

Tobias Kurpat (born 1997 in Leipzig) studies in the class for artistic action and research at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig with Prof. Christin Lahr. In his work, he explores virtual spaces as ideologically charged territories and analyses the tension between technocratic power structures, artificial intelligence and immersive media. In doing so, he critically examines the myths of Silicon Valley and pseudo-scientific narratives. In essays, painting, and digital practices, he explores how post-digital infrastructures can be designed, instrumentalized and aesthetically recaptured.

Sources

Adorno, Theodor W. & Max Horkheimer: Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical fragments. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer 1969 [first: Amsterdam: Querido 1947].

Dasgupta, Kushan, Nicole Iturriaga & Aaron Panofsky: How White Nationalists Mobilize Genetics: From Genetic Ancestry and Human Biodiversity to Counterscience and Metapolitics. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology 175/2 (2021), pp. 387-398; doi:10.1002/ajpa.24150.

Deleuze, Gilles: Nietzsche and philosophy. Munich: Rogner & Bernhard 1976 [French original: Nietzsche et la philosophie. Paris: PUF 1962].

Deleuze, Gilles & Félix Guattari: What is philosophy? Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 2000 [French original: What is it that philosophy? Paris: Editions de Minuit 1991].

Freud, Sigmund: The discomfort in culture. Vienna: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag 1930.

Heidegger, Martin: Nietzsche. European nihilism. In: Complete edition Vol. 47. Frankfurt a. M.: Klostermann 2004; available at https://www.beyng.com/gaapp/recordband/46.

Kant, Immanuel: Basics of the Metaphysics of Morals. Riga: Hardbone 1785.

Nietzsche, Friedrich: The will to power. Attempt to revalue all values, edited by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Leipzig: Naumann 1901 (retrieved via Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/60360/60360-h/60360-h.htm). [Not authorized by Nietzsche!]

Weber, Max: The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. In: Ders. : Collected Essays on the Sociology of Religion I. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1920 [first in: Social Sciences and Social Policy Archives 1904/5].

Photo Credit

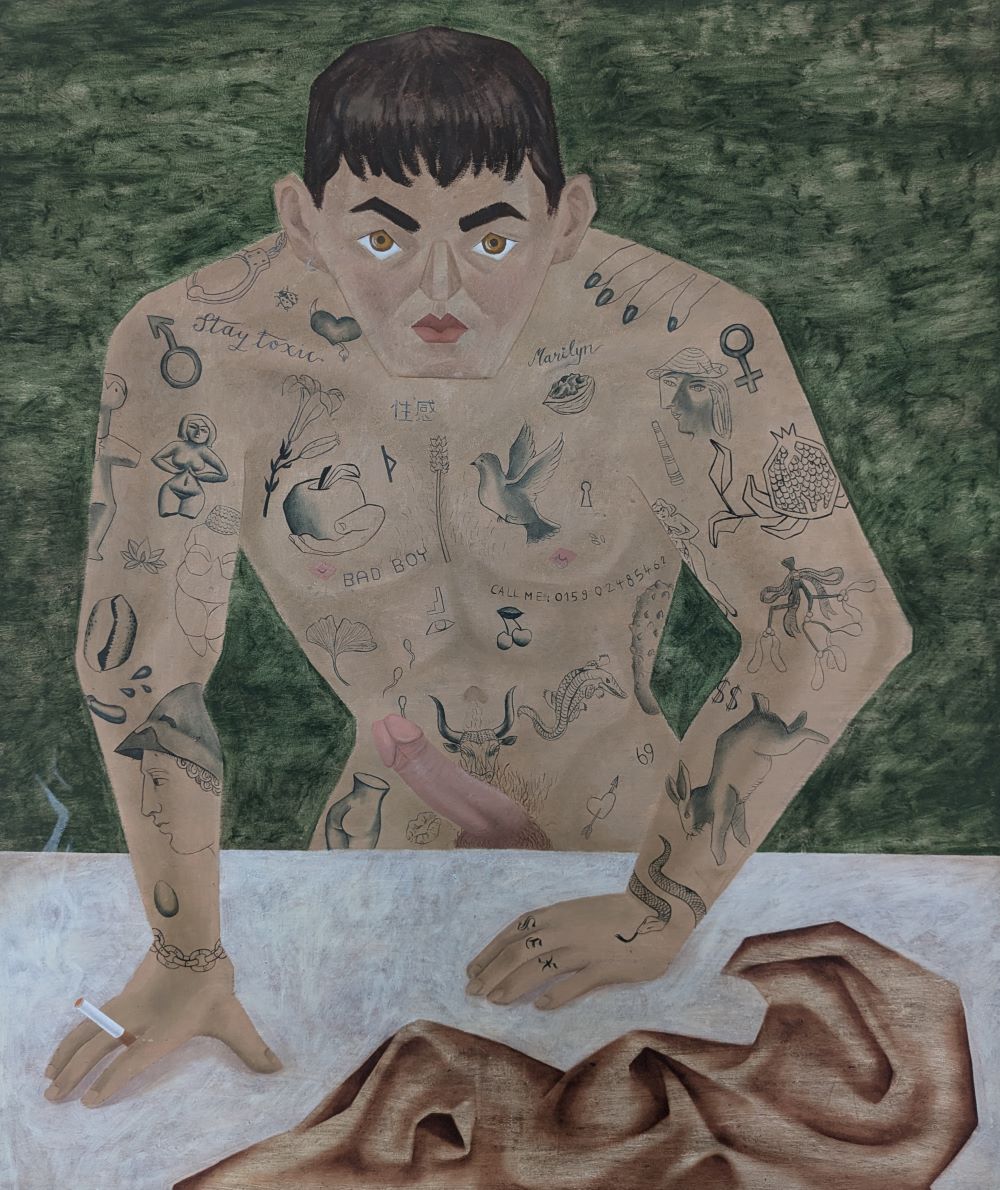

Article images: Excerpts from the installation “Photo album (Made in GDR)” by Tobias Kurpat (photographer: Sven Bergelt)

Portrait: photo by Aaron Frek

Footnotes

1: Subsequent fragments 1887, No. 13 [31].

2: Heidegger, European nihilism, p. 7 f. (§ 1).

3: “Hustle culture” describes a social trend in which constant work, productivity, and professional ambition are glorified. “Hustling” is presented not only as a means to an end, but as a desirable lifestyle, often at the expense of free time, health, and sleep.

4: Cf. weaver, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

5: Cf. Theodor W. Adorno & Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment.

6: Cf. Kushan Dasgupta, Nicole Iturriaga & Aaron Panofsky, How White Nationalists Mobilize Genetics.

7: Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Preface, 3.

8: Cf. Immanuel Kant, Basics of the Metaphysics of Morals.

9: Cf. Sigmund Freud, The discomfort in culture. For an in-depth analysis of this phenomenon using the example of the neo-reactionary “avant-garde” artist collective The Unsafe House, see my article When the avant-garde marches backwards.

10: Subsequent fragments 1887, No. 13 [31].

11: Cf. Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari, What is philosophy? and Deleuze, Nietzsche and philosophy.