Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Nietzsche certainly did not have any children and is also not particularly friendly about the subject of fatherhood in his work. For him, the free spirit is a childless man; raising children is the task of women. At the same time, he repeatedly uses the child as a metaphor for the liberated spirit, as an anticipation of the Übermensch. Is he perhaps able to inspire today's fathers after all? And can you be a father and a Nietzschean at the same time? Henry Holland and Paul Stephan, both fathers, discussed this question.

We also published the complete, unabridged discussion on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy YouTube channel (Part 1, part 2).

I. We as Fathers

Paul Stephan: How can you be a father with Nietzsche? Does studying his philosophy help you be a better father — or not? We want to discuss this topic in a completely open-ended manner below. But perhaps we should first clarify what, apart from the fact that we are Nietzsche researchers, qualifies us to talk about it in the first place. In fact, we will also start from our personal experiences, as we are both fathers too. Henry, you're the one of us who's a “more dad,” so to speak. How many children do you have and what is the personal background from which you look at this topic?

Henry Holland: I am the father of four children who are now between six and 23 years old. That means I first became a father when I was 26. All of these four children come from the same wife, my wife Rebecca, which can of course be completely different these days. There are two boys and two girls. It is also perhaps a bit unusual that we had actually already completed the life phase of having children and raising small children when Rebecca became pregnant again in 2018 and our youngest son Louis was born in 2019. The fact that Rebecca became a mother again shortly before her 42nd birthday is not so unusual these days — it was completely different in Nietzsche's time. But it was still a very nice surprise for us. — But what about you, Paul?

PS: I have to stress first that we will be recording this conversation on October 30 and will only publish it shortly before Christmas. Well, I have a son, Jonathan — he is now three but will be four on November 18th — and I am very excited right now and the topic of “fatherhood” is of great concern to me personally right now because my partner Luise is currently pregnant with our second child. It's still on the way now, but when we publish the conversation, it might be that time already.1 What we already know is that it will be a daughter, which actually makes me very happy. I wouldn't have a problem being the father of two sons either, I would love that too, but at least I imagine it to be another experience raising a girl.

HH: Yes, I can understand that and I was very happy back then that the first child was a girl. This may sound like an essentialist point of view, but when viewed from a constructivist perspective, it means that the children grow up necessarily influenced by existing gender roles — you simply cannot deny that, even if you want it to be different. I myself have tried to provide my daughters with all the freedoms and playrooms that I would have given to a boy — but I still notice in my own milieu: The more 'difficult' children are mostly boys, those who are more likely to stand out or rebel, who do not want to adapt socially, who rebel in the classroom. Even though many of us would like to free ourselves from existing gender norms, it can be assumed that these roles have and will have a long aftermath. Nietzsche articulates this perfectly in the Happy science:

After Buddha died, people continued to show their shadow in a cave—a tremendous dreadful shadow. God is dead: but the way people are, there may be caves in which you show your shadow for thousands of years to come. — And we — we must also conquer his shadow!2

PS: I would like to build on that, even if it takes us away from our actual topic. For me, an important aspect of being a father is that, as a father, you suddenly get to know a lot of other parents who have children of the same age as your own child. And in doing so, you can really make numerous surprising observations and findings. Although, of course, what you already said applies here: We cannot speak for “the fathers themselves.” We are starting from a specific milieu to which we both belong, a middle class intellectual milieu that primarily includes cultural workers and academics. And in this milieu, there is a fairly homogenous view that great care must be taken to educate children as “gender-sensitive” as possible, i.e., whenever possible, one should not make much difference between daughters and sons. I too think this development is generally very good and have set out to do so — but it was precisely against this background that I found it very interesting to observe that even very small children of one or two years, who are therefore still very “naughty”, are uninfluenced and are also brought up by parents who are very careful not to follow any stereotypes, often behave very stereotypically. Just one example: When my son was very young, around 1½, I went to early musical education with him once a week. That was very nice. It was a group of about six, seven children, boys and girls. It was really quite obvious that it was always the boys who roamed around the room, who tried to go outside and discover the room, who were rather loud and made 'nonsense' or even disturbed from an adult's point of view, that is, wild, while the girls were almost always sitting with their parent and were more 'too quiet, 'as opposed to that, insecure and shy.

I could give many such examples now. And of course I also know little girls in my circle of acquaintances who are very 'wild. ' But my average observation is really that you can notice all these cliché differences at a remarkably early stage — even with children whose parents are very 'gender-sensitive. ' This experience has led me to the conclusion that there is perhaps a greater influence of biology, genes, than you often think and claim. Of course, this is difficult to differentiate from the role of the unconscious character you were talking about. You will never be able to clearly differentiate between them and I don't even want to start the basic discussion of 'Nature vs. Culture' here — but the experiences mentioned have given me a somewhat differentiated opinion.

II. Nietzsche's Problematic Understanding of Man and “Woman”

HH: Perhaps this is a good reason to talk about Nietzsche and certainly the worst side of Nietzsche in terms of parenting, motherhood, fatherhood. We could perhaps work our way from his worst to his more witty and interesting statements. It must be emphasized that Nietzsche is hitting the table in some places with biological statements, for example when he writes: “Everything about woman is a puzzle, and everything about woman has a solution: it is called pregnancy.”3. This sentence is really one of Nietzsche's ten worst statements. It really seems — especially when you look at these sentences in isolation, which you shouldn't do — as though for Nietzsche, women are only there to become pregnant and serve the general good through this biological reproduction. And the women who don't do that should just shut up.4 Well, it's a very misogynistic statement. With regard to parenting, how do you deal with this very biological side of Nietzsche?

PS: Yes, I see this page the same way you do. It shows once again the big difference that separates us from Nietzsche. And there are countless places where he accordingly repeatedly expresses the clear view that women should be primarily responsible for raising children and having children, but men should, as is also the case in the passage you quoted from the Zarathustra means being a “warrior” and not worrying about the household and the children. In one sentence: “That is how I want man and woman: warworthy one, childbearing the other”5. And that may lead us to the actual main point of this conversation: Isn't it actually a contradiction to be a Nietzschean and a father in some way? Does Nietzsche even have anything to say to us fathers in the 21st century, who see us in a very different way? I think it is true for both of us and for most members of our milieu that we have a completely different understanding of fatherhood, as no one in the late nineteenth century has ever held: that you actually share the tasks of caring more or less with your mother, even when it comes to the very young children. These are things that might have been completely unthinkable even 30 or 40 years ago, which are perhaps not as widespread in other milieus even today, but which have already become very self-evident in our milieu. If Nietzsche could hear this development, he would probably, to say the least, put his hands over the head and diagnose the final “fall of the West,” the complete “feminization” and “softening.”6 The men, the final triumph of resentment-driven “general Ugliness Europe's”7. Do you feel the same way, Henry?

III. Paternity and Authenticity

HH: It seems to me that we can do that after all, that we can be Nietzscheans and yet be progressive parents in the 21st century. In this regard, I would actually come back to the concept of authenticity again and again — it just comes up again and again. You are much more familiar with this than I am, after all, you have just written and submitted an entire doctoral thesis on this topic. Authenticity is a very central concept for Nietzsche and I believe that what children are looking for primarily in us parents, both in fathers and in mothers, is authenticity. With fathers, however, in a slightly different form, because they tend to be more absent from the relationship and because the child expects this parent to remain authentic. And that means: Not only is static, but strives for authenticity, certainly in the spirit of Nietzsche's idea of selfBecoming as a creative, inexhaustible process of self-creation.

I'll try to make this concrete based on my eldest daughter, Alma. So she clearly shares my left-wing political views with me, which definitely expects, perhaps even as a basic condition, that I do not express myself in a gender-discriminatory or otherwise discriminatory way — and I actually am not, I don't do that. But that is not their main expectation of me that, to put it somewhat flatly, I always express myself 'politically correct', but that I remain authentic in my nature, in my actions, even outside the family, and that this authenticity can be retrieved and verified in some way.

Perhaps to make it even clearer and to build a bridge with my own father, who is still alive: He grew up in the final phase of British imperialism, when there were completely different values. One of the main values was this idea of “service.” You stand, you live life in service The other person — that's what you're there for. So you're there as a family man to earn money by doing a decent job in your outer life. The “self” doesn't come into conversation that much. So there is a certain class of British men, the very last thing they would talk about would be themselves. You hardly talk about it, it's more about this service principle. As a young man and as a young father, I often asked myself: What is my father's authentic self behind this existence in the service of others? What is its authentic core? And that often left me with nothing but a question mark, which is remarkable.

PS: Yes, it's very interesting and we seem to have had a very similar experience there. We came to the point shortly after during the preliminary discussion that it has become very difficult these days to gain an authentic understanding of one's own paternity, because the existing role models, which you could use to orient and work through in your own self-design, have become very fluid. It used to be very clear: The father is the one who earns the money. For example, there is this television series Breaking Bad, where this happens several times: “A man provides,” “a man provides,” even if those he provides don't even respect or love him. He doesn't care much about the kids at all. We are trying today to develop a different understanding of a present and caring, loving father.8

It was now very similar to yours with my father. Perhaps that is also the reason why I am so interested in the topic of 'authenticity. ' You have to know that my father grew up in the GDR. There is this catchphrase of “homo sovieticus”, which the Soviet philosopher and dissident Alexander Zinoviev coined in the 80s to describe the extremely adapted type of person that was called for and promoted in the states of the “socialist world.” As a hyper-opportunistic implementation of Nietzsche's dystopia of the “last person,” who imagines himself at the end of the story; a person without an inner center, who doesn't even strive for authenticity, but is completely absorbed in service to the community.9 I believe that this concept can also be applied to the GDR. Education in the GDR was even more strongly focused on the ideal of “service” than in the West; I think this keyword is very good. You shouldn't start from yourself; there were certain social expectations and you should meet them. I have always perceived my father, who is still alive, as a very inauthentic person. He is still a mystery to me in many ways, he is a very ironic person who hardly ever talks about his feelings and what is actually bothering him. You get the impression that he just doesn't have a good relationship with himself, and I noticed that even as a child and led me, I think, to try to become another man, another father. In this respect, my father actually served as a negative example for me, even though I don't want to blame him for anything. Especially when I was a little boy, he was also a very good father and took care of a lot. But I also felt this deficit, this distance from him, very early on.

And yes, there is indeed a close connection between these topics of “authenticity” and “fatherhood.” In any case, it appears often in my doctoral thesis, more often than I would have thought possible at the beginning of my research paper. But that may lead us to a slightly different understanding of masculinity. As already indicated, there is, on the one hand, this understanding of the man as a servant who sacrifices himself for the community, as Hegel articulated, for example, but then also the understanding of man as someone who completely stubbornly only thinks of himself, who places his own self-realization above everything else. And that is precisely the idea of masculinity that you actually find in Nietzsche, and around which his entire understanding of authenticity revolves — which, in my opinion, represents a huge problem. Just look at the following passage from the genealogy:

In this way, the philosopher perhorres [rejects with disgust] the wedlock Collect what would like to persuade her — marriage as an obstacle and disaster on his way to the optimum. Which great philosopher has been married so far? Heraclitus, Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, Schopenhauer — it wasn't them; what's more, you can't even look at them think As if married. A married philosopher belongs into comedy, that is my sentence: and that exception is Socrates, the spiteful Socrates, it seems, married himself, specifically at just this sentence to demonstrate. Every philosopher would speak as Buddha once said when the birth of a son was reported to him: “Râhula was born to me, a shackle is forged for me” (Râhula means “a little demon” here); every “free spirit” would have to have a thoughtful hour, given that he had previously had a thoughtless one, as it once came to the same Buddha — “closely pressed, he thought to himself, is that Life in the house, a place of uncleanliness; freedom is in leaving the house”: “Since he thought so, he left the house.” In ascetic ideal, there are so many bridges to independence indicated that a philosopher cannot hear the story of all those determined people who one day said no to all lack of freedom and in some desert Giengen: Assume that they were only strong donkeys and completely the counterpart of a strong spirit. So what does the ascetic ideal mean for a philosopher? My answer is — it will have been guessed long ago: the philosopher smiles at the sight of an optimum of the conditions of the highest and boldest spirituality, — he says no not Therefore “existence”, he rather affirms it being Existence and only his existence, and perhaps to the extent that the wicked wish does not abide by him: Pereat Mundus, Fiat Philosophia, Fiat Philosophus, Fiam! ...10

The following therefore applies: Even if the world were to end, philosophy should live, the philosopher should live, I should live. I think this quote contains a great deal of Nietzsche's understanding of freedom and authenticity, which is simply not compatible with fatherhood. The son is only described here as a “little demon” — and there are many such passages from which it is clear that Nietzsche, who was also known not to be a father himself, does not want to know anything about it. He believes that being a father is completely incompatible with philosophical, but also authentic, existence.

IV. Philosophers as Fathers — a Good Idea?

HH: Yes, that is an interesting passage. Although Nietzsche's thesis is, from an empirical point of view, contestable. Hegel had about two legitimate sons and another illegitimate son,11 Marx even had seven children with his wife Jenny, three of whom reached adulthood.12 — Although it is disputed whether Marx was also a good father.

PS: I would like to protect Nietzsche a bit there. It is remarkable that there are so many philosophers who have remained childless, lived partly as bachelors, and in some cases may have had a child.13 Well, you and your four children are definitely noticeable, I would say. Even more these days. But in the 18th/19th century, it was more the rule that you had five or six children, very large families — and philosophers were usually more of an exception. That this is the case has of course also to do with the image that the man should be the provider of the family and of course — as is still the case today, but it wasn't very different back then — it is often very difficult for philosophers to fulfill this duty.

HH: Although I wouldn't describe myself as a philosopher at all, but as someone who is interested in and works with philosophy! — In any case, my answer to this Nietzsche passage would be, in order to approach it a bit more economically and neutrally, that if he had lived in a middle-class household with marriage and children, he simply could not have written. His writing style, the writing process, his texts would have changed. This way of working, which was characterized by very short periods of productivity lasting nights and days, and then long phases in which Nietzsche suffered so severely from his symptoms of illness that he could put absolutely nothing on paper — it was impossible for a father to pull off this' ecology 'in a halfway' normal 'environment. The opposite is the case with the family fathers Hegel and Marx, whose main works came about much more slowly and are therefore much more saturated, have a completely different form and stringency.

Referring to Nietzsche's claim that so many great philosophers remained unmarried, I would simply like to ask the classic Marxist question: Who then did the reproductive work? So not only in terms of having children and raising children, but also: Who cooked lunch? Who cleaned? Who did the laundry? And the answer to this question, even in the case of Nietzsche, will surprise no one: 95% of them were women, mostly unnamed. I am thinking, for example, of Alwine Freytag, the long-time servant in the mother's household, who helped to care for Nietzsche in his last years — who knows her? There are always several people who did all this reproductive work in the background so that the “great philosopher” could write his works.

This may be self-evident to some, but it is often lost in the history of philosophy. And that, I think, is also the reason why we may no longer see works such as Nietzsche's. There is simply no woman or man, no one who could afford such a lifestyle anymore — I don't mean that purely economically, but from the point of view of what you feel responsible for yourself and what you don't.

PS: Yes, Nietzsche was completely dependent on the care of women for many years, as a child anyway and then again when he had mentally changed his mind. I recently attended the last annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society14 A very interesting and entertaining presentation was given by Ralf Eichberg about Nietzsche's failed plan to buy a portable oven. Based on the correspondence between his mother and him, it became very clear that, however, it was also a problem for the reindeer Nietzsche that he could not really afford servants but simply could not cook at the same time — much to his mother's concern. So his position wasn't that privileged — but in principle I agree with you, of course. It is true in general that philosophical work for centuries has largely been based on the work of women in the background, whether as servants, but also as secretaries or even unnamed co-authors.

When it comes to today's philosophy, that is of course the question: Is it progress or perhaps also a step backwards? Yes, Nietzsche's extravagant writing style has something to do with the almost stereotypical masculinity that he not only propagates in his works, but which this style also performs himself. But it is just an immature, puree masculinity. In the speech From old and young women, which, as already quoted, actually shows that women should not only have and educate children, their task is more comprehensive:

The man should be brought up for war and the woman for the warrior's recovery: everything else is foolishness.

Too sweet fruits — the warrior doesn't like them. That is why he likes the woman; bitter is even the sweetest woman.

The woman understands the children better than a man, but the man is more childlike than the woman.

There is a child hidden in ostracized man: he wants to play. Come on, women, and discover the child in the man for me!

A toy is the woman [.]

So in Nietzsche's imagination, the man remains a child all his life and should not grow up at all. And of course: This childishness, this immaturity that you retain, can, as in the case of Nietzsche and in many other cases, release great creative potential. But I do think that it is not bad for philosophy to start from a somewhat more mature and responsible attitude, as a father must automatically display and develop. I would also say the same for my own thinking, for my own philosophical, intellectual work. So becoming a father is of course a loss, not only a loss of time, quantitatively speaking, but also a loss of concentration in terms of quality. You can no longer write through for nights if you are woken up by a child every morning or have to take them to daycare. You are pushed more and more into a responsible and caring position, which, however, is not necessarily a hindrance to thinking, but rather leads to a deepening of thinking, which in particular involves thinking less strongly about yourself, but really engaging in this relationship with the other being — and I actually see this as a great asset both for myself as a person and for myself as an intellectual. It is simply not true, as Nietzsche mantraically asserts, that a “great culture” can only be created in such a way that a small caste of “masters” is unconcerned about the little things in life on the backs of millions of “slaves” and above all “slave”inside“live out — this leads to a castrated culture, this leads to exactly that decadence and alienation of life that Nietzsche so verbally warns about; and knows exactly that he himself is: A typical Decadent, the tragicomic result of a recent flourishing of a culture that was already in decline in its time and was based on exploitation and separation. The way out of cultural decadence can only lie in a non-decadent lifestyle — into production and even reproduction; overcoming the separation of head and manual work — but Nietzsche was only able to glimpse such an option when he jealously looks at the “birthing” ability of women and elevates it to a metaphor of authentic creative creation. As a caring father, he would also have been able to participate in this on a completely non-metaphorical level. — Although I don't want this to be understood as moral criticism, after all, it would hardly have been possible for Nietzsche to live another life in view of his illness.

V. Nietzsche's Personal Experiences

HH: Yes, I would like to take up this keyword of 'thinking about relationships with other people. ' Although I find it difficult to describe Nietzsche's style and attitude as 'immature. ' This is indeed a challenge, because if you didn't have this' halfway 'and' immaturity ', it wouldn't be Nietzsche again, his work would not have the authenticity that makes it so unique. It really is Nietzsches work.

But back to thinking in and about relationships. This deeper thinking in and about relationships with other people or about society, about political forms — I would say, for example, that Hegel has more to say than Nietzsche when it comes to the relationship between the individual and the state, which, I believe, remains an important philosophical issue. Nietzsche is on a genuine Societal thinking Not interested at all, that is not his topic.

As you have already indicated: Nietzsche has just, in line with his teaching of Amor Fati, made a virtue out of necessity. Nietzsche had a very difficult time in human relationships. He hardly cultivated those that could be described as “normal” in any sense, especially if they had any sexual component. This is perhaps most clearly shown by his brief friendship with Lou Salomé. He may simply have lost the ability to have long-lasting relationships, especially romantic and especially erotic ones — and he succeeds in creating an entire philosophy out of this coincidence. This conversion of philosophical coincidences into philosophers seems to me to be a general characteristic of Nietzsche's work. Why not? But that naturally raises the question of what other people can make of it.

Against this background, perhaps we should also talk about Nietzsche's own relationship with his father. That seems to me to be very central to our topic. He died when Nietzsche was five years old, so really early. However, this relationship was quite intense. Little Nietzsche was the only one who was allowed to stay in his father's study while he, a Protestant pastor, wrote his sermons and took care of the written community work. Perhaps because, unlike many other small children, he was very quiet and did not disturb so much. Although that is also noticeable. There are few signs that little Nietzsche played a lot with other toddlers and let off steam. Nowadays, his father might have taken him to the therapist earlier — and the early death of his beloved father has certainly reinforced this unusual tendency in little “Friedrich.”

There is a quote that is very relevant to our topic, about abandonment by one's own father, about his absence and about how much this experience shaped early Nietzsche. It is a childhood memory of Nietzsche, which he wrote down shortly before his 14th birthday, in one of the remarkably numerous autobiographical writings from his youth. It is about the time after the death of his father and the death of his little brother Ludwig Joseph shortly after:

At that time, I once dreamt that I heard organ sound in church just like at a funeral. Since I saw what the cause was, a grave suddenly rose and my father in death-dress emerges from it. He hurries to church and returns shortly with a small child in his arms. The burial mound opens, it climbs in and the ceiling sinks back onto the opening. The rushing organ sound is immediately silent and I wake up. — The day after that night Josephchen suddenly becomes unwell, gets the cramps and dies within a few hours. Our pain was tremendous. My dream was completely fulfilled. The small corpse was also placed in the father's arms.15

Of course, you can't know whether this is a real memory and how much Nietzsche poetically added to it as a teenager in view of his lyrical tendency. But there is still a memory that is about being abandoned and farewell — and it raises the question for me how much Nietzsche has brought to a philosophy that revolves very much around the “strong individual,” in which it is made a virtue that you isolate yourself, that you should not rely on the other person, that as a man you should not marry and not have children. And this seems to me to be diametrically opposed to our understanding of fatherhood, which is primarily about being there for the child, being there for conversations, playing actively with the child, i.e. creating an active relationship with the child.

PS: Yes, the absence of his father is mentioned in almost all biographical texts on Nietzsche as an essential factor in his personal development and I completely agree with that. Perhaps there is in fact also, unconsciously, repressed, a lot of disappointment and anger, spoken with Nietzsche himself: resentment, towards the father. Because as a child, you may experience such an event not so much as a stroke of fate, but as if the deceased parent had deliberately abandoned you. You have to struggle with this experience all your life. And even in the case of Nietzsche, that may be a decisive reason why, it must be said so clearly, he really generally fails in interpersonal relationships.

So what I would also like to emphasize very clearly at this point: I am of course not of the opinion that you absolutely have to become a father in order to enter into a caring, responsible relationship with others as a man; there are of course many other ways of realizing this. Fatherhood is one of them, a romantic relationship of two too, of course, there are many options. But you can certainly say that Nietzsche has generally failed in this regard. So there is no example almost in his life of a really successful interpersonal relationship over a longer period of time at eye level — which is of course absolutely sad, but should also shed some light on his thinking.

And then there is also this somewhat funny story with Lou Salomé. It makes sense to counter Nietzsche: He says that the married philosopher belongs in comedy — but the philosopher, who has had a large number of failed marriage proposals behind him, belongs there much more. In any case, he certainly wanted it for a while. However, you also have to see that letters repeatedly show that he wanted to marry primarily for pragmatic reasons in order to be better provided for materially — or even to have a “free nurse” or assistant, so to speak. Although this is certainly something else in the case of Lou Salomé, he certainly saw her as an exchange partner at eye level and probably also as a romantic-erotic object of desire in some form — although I don't want to address the topic of Nietzsche's exact sexual orientation at all, especially since it has already been discussed extensively on our blog anyway.16 But the pragmatism, sometimes downright cynicism, when it comes to marriage, which he sometimes allows to shine through in his letters, certainly doesn't exactly speak for him.17

But, as always with Nietzsche, there is also a passage in the work on this subject where he represents exactly the opposite. I have found at least one from his middle creative phase, a short note from the estate of 1881, which states:

Having descendants — that is what makes people stable, cohesive and able to do without: it is the best education. It is always the parents who are brought up by the children, and by the children in every sense, even in the most spiritual sense. It is our works and students that give the ship of our life the compass and direction.18

Unless I've overlooked anything, this passage hasn't made it into the published work either, but I think it's really great. It is also much more in line with my own position than the almost somewhat creepy passage from the genealogy, from which I quoted above. The fact that children also “educate the educator,” that education must generally be understood as an interplay, as a maturing process in which parents also mature first — I think that is a very clever idea. From my own experience, I can definitely confirm that this is the case, and I would therefore say that it would have been very good for Nietzsche to be able to take this further step of education. As I said: That is not a moral criticism, it was rather his fate and he certainly understood how to make the best of this fate and then he just ex post thinks of a philosophical justification for this. Just like most philosophers.

I see two possible scenarios. One day, that Nietzsche as a father would have stopped dealing with philosophical topics and really only cared about “providing” — or that he would have continued his philosophy anyway and perhaps even better books would have come out if he had succeeded in, this childish narcissistic aspect, which he definitely has very strong, and a somewhat more responsible view of society, of the big picture, in which you as a Father is almost brought up to bring together. Perhaps then he would really have become the greatest philosopher of the 19th century. It's possible, isn't it?

HH: Yes, it is possible and I really like this mind game. Although I would of course prefer the second option. If he had found someone on equal footing, if he had succeeded, he would certainly have created a very different work, perhaps a much more mature work.

What else I find important to mention at this point: What were Nietzsche's encounters as an adult with small children? There aren't many, all notable meetings took place in the Wagners' household, from 1869, when Nietzsche had just taken up his professorship in Basel and was regularly invited to the Wagners' country estate in nearby Tribschen. At this point, Cosima was still married to her first husband Hans von Bülow, but Richard Wagner and she had already been in a relationship since 1864 and had lived together since 1867, had even begun founding a joint family with two daughters, Isolde (born 1865) and Eva (born 1867). In May 1869, Nietzsche visited Tribschen for the first time and Siegfried, the couple's third child, was born as early as June. And this is where it gets interesting: The biographer Sue Prideaux19 Does it actually mean that Nietzsche was so far removed from life in everyday life that he almost did not notice that Cosima was pregnant when he visited the Wagners in May — which would have been a piece of art, in fact it couldn't have been the case at all. And it was even the case that Nietzsche was there the night Siegfried was born, and he simply did not even notice it, not even the screams that certainly accompanied it. He only realized the birth at breakfast, when the new person present could no longer be overlooked. — That's the version of the events, as Prideaux tells them, anyway. And even though that may be an exaggeration, this anecdote very well reflects something of Nietzsche's great alienation from the world.

PS: Yes, he was certainly not the most emphatic person, always lived something in his own world, you can imagine that very well.

HH: Although Cosima and especially Richard later played seriously with the idea that Nietzsche should take on a kind of teaching role for Siegfried. In 1872, Wagner uttered such simulation games to Nietzsche in two letters, going so far as to bring Nietzsche into the game as a kind of substitute father for “Fidi” — and accordingly Nietzsche himself as Wagner's surrogate son.20 However, Nietzsche showed no interest in this, because both times he simply ignored the request of his “beloved master,” as he still called Wagner during this time.21 So it seems that Nietzsche did enjoy his repeated visits to Tribschen in the midst of a household of young raging children, but that he did not find a way to further expand on this experience in his own biography.

PS: Yes, I think building such a relationship with a child would definitely have been good for Nietzsche. But you also have to see that the Wagners did not always have the best intentions towards Nietzsche. Christian Sährendt speaks in an article about the Nietzsche/Wagner relationship on our blog also from a “terribly nice family” that the young professor went to there. Perhaps this plan was also about simply exploiting Nietzsche — but perhaps he had also felt that it would have promoted Nietzsche to take on a kind of father role.

HH: I think we should start from good intentions, even though bad intentions cannot be ruled out, of course. In any case, it should be noted that there was certainly this phase in which Nietzsche, as the Wagners' 'house friend, 'had regular contact with small children — but it is unlikely that he used this opportunity to establish an intensive relationship, for example with the young Siegfried. Siegfried Wagner will hardly have noticed any kind of father figure in Nietzsche; it stuck to a mind game. — Perhaps this will take us on to address what Nietzsche wrote about childhood in general.

VI. Nietzsche's Affirmation of Childhood

PS: Yes, we should definitely talk about this topic! It is really remarkable that Nietzsche hardly ever had anything to do with real children, but is certainly one of the thinkers who said the best things about childhood and pregnancy.

The pregnancy metaphor is found primarily in So Zarathustra spoke. It has, of course, a misogynistic component in the sense that Nietzsche, as we have already discussed, starts from a strict division of the sexes in this regard and fixes both in a specific role. But it must also be said that Nietzsche also extremely values giving birth and sees it as a metaphor for the ability to create creatively. Men can also be “births” with him and have children, including Zarathustra or himself. Against this background, feminist interpreter Caroline Picart even speaks of “Nietzsche's incurable oath of childbirth [Womb Envy]”22. It is therefore in a certain sense a devaluation, but also an appreciation and there is a whole strand in the female-feminist reception of Nietzsche, in which women relate positively to this side of Nietzsche's work, starting, interestingly enough, with Lou Salomé to the important difference feminist theorist Luce Irigaray.23

But even more important for our topic is the metaphor of the child. There are numerous profound passages in Nietzsche's work here, which have inspired me time and again as a father, and which can only be explained by the fact that Nietzsche remained a “big child” throughout his life, retained a great childishness and was therefore able to write very well about childhood, even though he lacked empirical experience. To give just one of countless examples, I am thinking of this famous sentence from Beyond good and evil: “Man's maturity: that means having rediscovered the seriousness you had as a child while playing. ”24 That's a special term for “maturity,” of course, but when I watch my son playing, he shoots through my head over and over again and he already has a truth. Children are sometimes so incredibly absorbed in their games, they take them so seriously. The adult often makes fun of this and interprets this seriousness of the unimportant as childish and immature — but doesn't he also envy the child for this ability and are we adults so different when we get excited about something?

And there are also countless passages on this aspect in Zarathustra. There is, for example, a passage from the book that Swedish feminist author Ellen Key (1849-1926) also wrote her book The century of the child (1900), a classic of reform education, as the motto:

Yours Kinder Land You should love: this love is your new nobility — the undiscovered one in the farthest seas! After him, I'm looking for and searching for your sails!

On your children shall you Do wellthat you are children of your fathers: everything past shall you thus Redeem! I'm putting this new board above you!25

Interestingly enough, this could even be interpreted as a plea for fatherhood26 But it is primarily to be understood as a plea for childhood. That children's openness and creativity should almost be taken as a role model for a creative, life-affirming attitude. And there are also countless places where the playing child actually acts as a metaphor both for the creative person who is on the way to becoming superman and for the superman himself.27

Sure, that's a romanticizing understanding of childhood that, as a real father, you might not share 100% — and that's why Nietzsche knows that too28 —, but in principle, these are great sentences that should encourage us not to completely lose our own childishness even as fathers and perhaps also to learn from our children to rediscover our own childishness, that is also a side of being a father, isn't it?

HH: Yes, this impartiality or even indignity, this ability to completely lose oneself in the game, which we see especially with smaller children, is also found in many of Nietzsche's texts. I think what sets him apart from many other writers — and I tend to actually compare Nietzsche with particular writers rather than with other philosophers, I see him more and more as an artist and only as a subordinate philosopher: He often has very little self-censorship, just like small children. We experience this time and again with our six-year-old Louis, this complete openness even towards strangers in the message. On the train, for example, he meets a completely unknown person and simply starts talking about details of family life that no adult would ever tell just like that — because the vast majority of adults have internalized a certain self-censorship, we are already thinking pretty carefully about what can and cannot be said. Especially when we write, especially when it is something that goes in the direction of science, then we think even more carefully, then this self-censorship works even more strongly. I often think of George Orwell's insight that this self-censorship is even more powerful than censorship itself, i.e. what we filter out ourselves before we even submit a text.29

And that's the great thing about Nietzsche: Of course, he carefully edited his texts before they were printed, but they still seem as if he were talking straight ahead, as if he were not self-censoring, speaking completely authentically. And that can go both ways, of course — sometimes this openness makes him write terrible things, but sometimes it also leads him to real wisdom and jewels. That is almost the biggest thing we can learn from children.

And I also like this idea from the other quote that children are the educators of adults. It's a really great subject. And I don't find that romanticizing, it's already real. The challenge is simply to live this authentically in everyday life. For example, what our Louis wants to do with me often, less with my wife Rebecca, that is what he called Toy Fight, 'game fight. ' He often wants to do this right after getting up, around half past 7, even before breakfast. Above all, that means jumping on dad pretty wildly. Of course, there are a few rules of the game, so you can't scratch, don't bite, don't pull your hair and you can't hit certain sensitive areas — but apart from these four basic rules, it's relatively random, you can do more or less everything and that's another opportunity to live an uncensored self, which can contribute to the development of an authentic self. I think that is something that we, regardless of whether we are fathers and have children or not, lack in everyday life, because it is so incredibly structured and thoroughly scheduled. And digitization has also failed to bring the hoped-for liberation; rather the opposite is the case. Our time is simply becoming more and more economical; everything should be able to be planned. And I do believe that our children give us the opportunity to free ourselves from it, even if it is only for 20 minutes, to free us again and again — and that is something I would not like to miss.

VII. Once Again: Masculinity and Femininity

PS: Yes, I can only agree with that; I have a very similar experience there. Where I would like to follow up with regard to the topic of gender and gender roles: It is also interesting how children very intuitively assign different roles to parents and raise different expectations of them. It is also the case with us — and this is not possible, at least not consciously, on our part — that very different things are expected of my partner and I. From me in particular this fighting, it's almost exactly the same for us, there is always a lot of “fighting” — but Jonathan almost only wants to do that with me. Sometimes even with Louise — which of course doesn't work particularly well right now that she is heavily pregnant — but above all with me he wants to fight and do 'fighting things, 'which are more stereotypically masculine, while he is more likely to cuddle extensively with Louise, make out and do rather tender things. With him and me, on the other hand, he doesn't necessarily want to do such things and also makes me understand that — which is of course perfectly fine, even if it sometimes offends me a bit.

HH: We also have “toy fighting” just with me, Rebecca simply says “no” and doesn't feel like it — in return she does a lot of other things with Louis. You can speak of “stereotypes” here, but from a philosophical point of view, you could also call it something else. For example, you could bring the term “archetype” into play for her — but then you're moving on thin ice right away. Perhaps to put it more neutrally: Many specific behaviours remain counteracted, whether we like it or not, that is precisely our cultural heritage. A specific example: knitting. Maybe the circles I'm in are the wrong ones and not progressive enough, but I don't know a single man who knits. Of course I've seen photos of such men, but I don't know anyone. On the other hand, I know a number of women who knit — Rebecca, for example, knits very well, she makes insanely great fashionable sweaters and something like that that are almost works of art. She also taught Louis how to knit fingers; for example, he can make small scarves or something like that himself — that is a very real skill, a skill. In other words, these are skills that do not naturally belong to any gender, but which are also assigned only to one gender for cultural reasons and are passed on accordingly.

And perhaps to give another example, even though it may be a bit profane: In Great Britain, there are the “Ladybird Books”, which are small-format books for small children, comparable perhaps a bit to the German Pixi books, which have had a mass edition. So all middle class children in my generation had them, they simply had good quality and very good illustrations — but many were written in the 1950s and 1960s and therefore fall very much into gender stereotypes, both as regards girls and women as well as boys and men. It really uses all clichés. Recently, as a post-modern joke, the publishing house released something called “Ladybirds for Grown-Ups,” for adults, i.e.30 That takes this whole thing on the arm, there is something like a book that simply means The Dad. The father is stereotypically standing at the grill and there is something like — the lyrics are very short, just like in real children's books: “That's the dad. He seems complicated, but he simply lives off beer and sausages. “That's all it says. My wife Rebecca and I actually find that very funny because we know a lot of fathers who are really like that.

What I'm getting at is that this is the dichotomy in which fathers of our generation are stuck, that we still have a strong cultural and social heritage — we're talking about centuries that were very different — and have only been trying to get out of it for about 40 or 50 years, but we just can't do it right away. These simple fathers, who could not or barely show their feelings, let alone talk about them, who were somewhat simple in this regard — they remain in us as an inheritance that perhaps needs to be overcome.

PS: Yes, ten horses wouldn't get me to knit either, even though I enjoyed doing it for a while when I was around eight or nine years old. — But I wanted to say a little counterspeech at that point. Well, let's not go unmentioned, there is also no pure biologism in Nietzsche. There are, for example, in the Götzen-Dämmerung this remarkable sentence: “The man created the woman—from what? From a rib of his god — his' ideal '...”31 And there are many other such places where it is shown that Nietzsche, as a historically thinking person, is already aware that gender roles are absolutely changeable, “socially constructed,” as you would say today.32

The other thing is, as already indicated, that his statements about women are not meant to be derogatory at all. Even in From young and old women Among other things, it also says:

A toy is the woman, pure and fine, like a precious stone, irradiated by the virtues of a world that is not yet there.

May the ray of a star shine in your love! Your hope is: “May I give birth to Superman! ”

Similar to the playing child, it is not only the man as a “warrior,” but also the woman giving birth as a symbol and physical appearance of the superman and Zarathustra and even his own work are repeatedly equated with giving birth — even in this speech himself. And it should also be clear that the notorious “whip sentence” from this speech can also be interpreted in the sense of such constructivism.33 But even reading essentialistically, there are and were numerous women and feminists who have adopted this side of Nietzsche positively, affirmatively and were inspired by it in their definition of femininity.

So my position in this regard is very clear that it is a problem when there are these repressive norms, these stereotypes, and you have the pressure to adapt to them because they simply do not reflect the diversity of the human species and leave little room for deviation. It is a good process in that they are dissolving and becoming more flexible at the moment. But at the same time, you also have to see that these stereotypes are not only arbitrary, but that there is already something called a biological substrate in some form. This is of course difficult to determine; you will probably never be able to define it in its pure form. But there is evidence that this stereotypical behavior can already be observed in small children and therefore cannot be purely educated. This is a fact that, despite all criticism of repressive gender norms, cannot be ignored. It is also undeniable that certain hormones, such as testosterone in particular, have an effect on mental life. It just does something to people when they naturally have higher testosterone levels.34

You just have to be careful, and that's where Nietzsche comes into play again, that you don't replace one repressive morality with another. All people should be equal; as a man, you simply must not behave too masculine, and as a woman you must not behave too feminine. I would say: No, it's okay to live according to predetermined stereotypes. Why should you bend over there? That can certainly be an expression of authenticity.

Quite apart from biology, it also makes sense that there is this division of roles. Interestingly enough, homosexual couples are also often unable to break away from her and one partner is more likely to take on a “female” role in them and the other a more “male” role. This involves dividing up certain tasks, although care should of course be taken to design them fluidly and situationally so that both partners can develop equally.

HH: Yes, I completely agree with you that it makes no sense to replace one repressive morality with another. Although this could be seen as tricky in some circles. This whole topic of Manosphere, i.e. one Bubble On the Internet, which is about creating a new sense of 'real masculinity, 'in contrast to' wokeness' and feminism, and which is often perceived as very sexist and misogynous (and is certainly also in large parts), that has already become a very hot topic. Christian Sährendt has already addressed this topic on our blog in his article on the question of whether Nietzsche was an “Incel”. When there is talk of men and fathers in public discussion at all, it is usually about this topic of “toxic masculinity.” But what if you don't want to become or remain “toxic” — is there a public space to discuss it openly? Some have come to the interesting view that that is precisely why some men are so susceptible to this Manosphere- Get spelled because there are so few models of good, non-toxic masculinity or paternity so far. And it is also striking in this social equality debate — which must continue for good reasons — that a sub-chapter of this discourse is that both the best and poor life results in the global North are achieved by men. As a man, you are therefore more likely to be very rich or successful — but also to commit suicide, to suffer from an addiction, to die young, that you simply won't be able to eat properly, or become long-term unemployed — to name just a few of the worst life events that are particularly strongly associated with men. It's also part of being a father, managing the balancing act of being a good father without ending up with these worst results.

Or, to be more specific: Why do so many of these men and fathers vote for Donald Trump or right-wing populist parties? Of course, women also vote for him, but there are significantly more men. Not because they are all so well protected or privileged — on the contrary, it is the case that millions of them live so precariously that they are outside the social mechanisms and no longer have any confidence in making their own living conditions better; instead, they bet on a 'big throw, 'a 'Trump throw; this idea of being a 'tough man,' a toxic man, who you without any social Insurance gets through.

So it's definitely a bet on our part to publicly discuss such a topic as fatherhood at a time when public discourse about men is primarily characterized by this concept of 'toxic masculinity — I hope this bet turns out well.

PS: Yes, I also perceive that there is a vacuum, an absence of role models of non-toxic, responsible masculinity and fatherhood — which leads to great disorientation, especially among young men, and to the fact that they flock to replace wannabe “supermen” such as Trump, Musk or even Putin. The old “idols” have fallen, but no new ones have taken their place — and, paradoxically, this is leading to a frightening renaissance of such pseudo-archaic “barbaric” figures. But we emancipated men should not mourn this vacuum, in a completely Nietzschean way, nor fall into nostalgia, but as an opportunity for a new cultural start, to create a new, better understanding of masculinity and fatherhood. As fathers, we in particular are called upon not only to preach such an understanding, but above all also to live by, hopefully, to serve our sons not only as negative repulsive figures, but also as role models from which they can grow — and then of course repel ourselves from us again, that is unfortunately also part of being a father.

In essence, my point is that you should simply strive for your own, authentic understanding of fatherhood and masculinity — and, of course, of motherhood and femininity — which is independent of existing stereotypes. But it would also be inauthentic, and simply not particularly healthy, not healing for yourself, to now desperately want to free yourself from these stereotypes at any price — both in terms of your own self-image and in terms of your own educational practice. I already notice such tendencies in my environment that, for example, people want to avoid boys playing with weapons or being interested in war at all costs — and perhaps trying to force girls to do just that. And you get the boys to play with dolls. Well, this is of course an exaggeration, but there are already tendencies of this kind that I cannot approve of.

In general, I do not find this whole discourse about 'toxic masculinity unjustified. ' I think there is. By the way, there may also be a type of 'toxic womanhood, 'i.e. stereotypical female or even maternal behavior that is not particularly healing for those around them. They only appear more subtly, for example in forms of emotional manipulation and blackmail. Although, of course, the question is: What does “toxic” actually mean? Isn't that a very vague term?

So I think it's generally good that such behaviours are being questioned, both among women and men. But at the same time, I also observe a certain insight or even discrimination of typical male behavior, which is definitely At least It is hypocritical, because precisely these behaviours also have their social justification and are in many cases necessary in today's society. Even people who are very upset about typical male behavior may also be happy when there is a tough police officer who defends them in an emergency. And there is now a lot of talk about a “turning point” and rearmament — which I find problematic again for other reasons — but you just have to want both, you can't say that you have these masculine behaviors that you display as a soldier must, are very bad and problematic, but at the same time we need a lot more soldiers and at least everyone men — Why just them? Does this perhaps also have something to do with biology? — should do military service again. So I see a certain contradiction in our society and in the debates on this topic. Speaking in general terms, you should perhaps simply recognize that some of these typically male behaviours are not that bad at all and have their right, unless they are pushed to a certain extreme.

The best example is Nietzsche himself, who was perhaps in some way, if you want to use this term, a “toxic” or at least stereotypical man. We have discussed this and there is a lot to criticize about it, but this attitude in turn also enables him to create his great work. I believe that it would also have been good for the work if Nietzsche had questioned his own masculinity more — but would it really have come about without the infantile narcissism that Nietzsche cultivated?

And even with myself, I notice that, even though this is partly not my nature at all, I am being driven into such a masculine role, which I would define as having a slightly different parenting style, that in certain stressful situations, you are more likely to remain calm and make clear views. I think that is something that is simply needed, which you might then also achieve as a man must. Sure, on the one hand, I fail often enough, and secondly, there are also situations in which my partner takes on this part, but I think that this part, this perhaps slightly “authoritarian” part, is sometimes needed, and then it would perhaps be more important that you take on this male part in a non-toxic and responsible way, but also not completely reject yourself. I think that there is something very infantile about this new 'post-modern post-masculinity, 'that is to say again a' toxic 'masculinity in a different way — in Nietzsche's way. You actually remain a child, you relinquish responsibility, you no longer want to be' authoritarian 'at any price or something like that, you speak very softly, don't spread your legs when sitting... So this infantie It is linked to an extremely moral and self-negative attitude. This is once again a one-sided development, an escape from responsibility and also from authenticity, because I certainly perceive that such men are not in an authentic self-relationship, but rather artificially suppress a side of themselves that they should perhaps live out more strongly. You should learn to appreciate the 'inner man, 'the 'inner father' — that is perhaps our task in the current situation.

HH: Wouldn't that be a good way to end our conversation?

VIII. “Become like the children! ”

PS: I might add something else. We've talked a lot about Lou Salomé and about Nietzsche — it might make sense to talk about the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), who was about a generation younger than Nietzsche and, funnily enough, was not only friends with Lou Salomé, but perhaps succeeded in what Nietzsche dreamed of, i.e. was in a relationship with her. Funnily enough, he took on the role of a 'big child again and Lou a maternal one — that is perhaps not even that rare among poets and thinkers. In any case, there is a great poem by him in which he expresses this attitude of becoming a child in even more lyrical and impressive words than Nietzsche, and I would very much like to end our conversation with that:

Dreams that surge in your depths,

out of the darkness set them all free.

They're like fountains, and they'll fall

brighter, and in the intervals of a song,

back into their basins' lap.

And I know now: become like the children.

All fear is but a beginning;

yet endless is the earth,

and the trembling is only the outward sign,

and longing is its meaning —35

That may be a good final word: “And I know now how the children will be.” But maybe then you also have to take on more responsibility — but that's the philosophical level again.

HH: I really agree with that. Thank you Paul for this enlightening conversation.

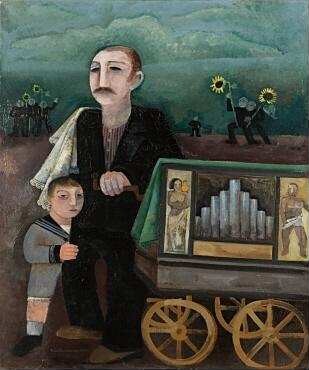

The article image is a painting by Felix Nussbaum from 1931, Leierkastenmann. Photographer: Kai-Annett Becker. Source: https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/6CQPR6PYR3GSAEFLYDCJDO7VC7ZKNCK7

Bibliography

Who is the”Homo sovieticus“? A dialogue of Narthex-Editorial with Vitalii Mudrakov. In: Narthex. Radical Thinking Booklet 6 (2020), P. 56-63.

Diethe, Carol: Forget the whip. Nietzsche and the women. Transformed by Michael Haupt. Hamburg & Vienna 2000.

Key, Ellen: The century of the child. Transformed by Francis Maro. Berlin 1905.

Kimmel, Michael S.: Masculinity as Homophobia. Fear, Shame, and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity. In: Harry Brod (ed.): Theorizing Masculinities. Thousands Oaks 1994, pp. 119-141.

Orwell, George: Animal farm. A fairy tale. Transated by Ulrich Blumenbach. Munich 2021.

Picart, Caroline: Classic and Romantic Mythology in the (Re) Birthing of Nietzsche's Zarathustra. In: Journal of Nietzsche Studies 12 (1996), PP. 40-68.

Prideaux, Sue: I am dynamite. The life of Friedrich Nietzsche. Transated by Thomas Pfeiffer and Hans-Peter Remmler. Stuttgart 2021.

Rilke, Rainer Maria: Poems 1895 to 1910. Works Vol. 1st ed. by Manfred Engel & Ulrich Fülleborn. Frankfurt am Main & Leipzig 1996.

Stephen, Paul: Left-Nietzscheanism. An introduction. 2 vol.E. Stuttgart 2020.

Ders. : “Don't forget the whip! ”. An examination of the metaphor of the “woman” in So Zarathustra spoke. In: Murat Ates (ed.): Interpreting Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Marburg 2014, pp. 85-112.

Wagner, Richard: Letter to Nietzsche v. 25/1872 (No. 333). In: Letters to Friedrich Nietzsche May 1872 — December 1874. Critical Complete Edition Correspondence Vol. II/4. Ed. by Giorgio Colli & Mazzino Montinari. Berlin & New York 1978, p. 29 f.

Ders. : Letter to Nietzsche v. 24/10/1872 (No. 372). In: ibid., pp. 102-106.

Footnotes

1: Status 12/20: Our daughter is still taking her time.

2: Aph 108

3: So Zarathustra spoke, From old and young women.

4: It is also said elsewhere: “We men wish that the woman does not continue to commit herself through enlightenment: what it was like caring for men and protecting women when the Church decreed: mulier taceat in ecclesia! “(Beyond good and evil, Aph 232) And with reference to the mentioned notorious passage from Zarathustra Does he write in Ecce homo: “'Emancipation of women” — that is the instinct hate of the wrongful woman, that is, the womanized woman against the well-behaved” (Why I write such good books, paragraph 5).

5: So Zarathustra spoke, From old and new boards, 23.

6: Human, all-too-human II, Preface, paragraph 3.

7: Beyond good and evil, Aph 232.

8: This concept of masculinity is also found in philosophy, especially in Hegel in his Principles of the Philosophy of Law (1820), this terrible apology of the inauthentic person who finds his “true freedom” in the victim, whether as a “marketplace man” — a term used in critical research on masculinity (see Michael S. Kimmel, Masculinity as Homophobia) —, be as a loyal bureaucrat in civil service, be it, in his highest form, as a soldier who falls for the “fatherland.” The Soldier and the “Warrior” — this is where, strangely enough, Hegel and Nietzsche meet, even though Nietzsche is more about the resolute will to self-actualize. Still in the 18th Century, Just Think of Rousseau's emile (1761), this big plea for an active father as a responsible educator of children, was thought about it in a completely different way — but it was precisely this image of the caring father that Nietzsche turned against when he spoke of the “softening” of Europe!

9: See also Who is the”Homo sovieticus“?

10: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 7.

11: There is also a daughter who died very early. Hegel assumed educational responsibility for his illegitimate son, at least temporarily.

12: There may also be an illegitimate son.

13: The extreme case is perhaps Rousseau, who, as mentioned (see footnote 8), championed the idea of committed fatherhood — ideally only with one child, of course — but without exception gave his own children to the orphanage.

14: See Emma Schunack's report on this blog (link) .1

15: From my life, The adolescent years.

16: It is sufficient to point out here that it is anything but obvious that Nietzsche was interested in women in sexual terms at all. cf. Dionysus Without Eros by Christian Saehrendt and The interview I had with Andreas Urs Sommer about his new Nietzsche biography.

17: On Nietzsche's temporary efforts for a wife, cf. Christian Saehrendt's article Dionysus without Eros On this blog. However, it should be emphasized here that only one application to a woman, the young Russian woman Mathilde Trampedach, is actually clearly substantiated. As the commentator “Rafael” rightly points out, there are legitimate doubts about the thesis repeatedly put forward in research that Nietzsche, depending on the variant, asked Lou Salomé's hand once, two or even three times. There is no contemporary evidence for this story; it is based almost exclusively on Salomé's own autobiography (see also in more detail This blog article). — There is no doubt about Nietzsche's desire to marry, in any case temporarily (see e.g. Bf. to Malwida von Meysenbug v. 25/10/1874). On April 25, 1877, he told his sister about the plan to marry a “necessary [] woman” in order to be able to give up his arduous professorship (link). He Hopes for a Marriage at That Time, So In a letter to Meysenbug dated July 1, 1877, a “alleviation [s] of suffering.” He later writes to Franz Overbeck — ironically, briefly, Before He gets to know Lou Salomé in person, in view of his deteriorating health: “Now my friends have to invent a read-read machine for me: otherwise I will be left behind myself and will no longer be able to feed myself enough mentally. Or rather: I need a young person close to me who is intelligent and knowledgeable enough to work with me Work To be able to. I would even marry two years for this purpose” (Bf. v. 17/3/1882). He later reported to Overbeck that his mother wanted to marry him in order to provide him with a “caring nurse” (Bf. v. 6/10/1885) — but he had already completed this idea at this point, as he wrote to his mother himself at the end of April of the same year: “My dear mother, your son is ill-suited to getting married; Independently Being up to the last border is my need, and I have become extremely suspicious for my part in this Einen Points. An old woman, and even more of an efficient servant, would perhaps be desirable to me” (link). — These letters attest to Nietzsche's rather pragmatic relationship to the subject of marriage, which, as Carol Diethe Argues (cf. Forget the whip, p. 38), such statements always Cum grano salis In His Letters, Nietzsche often shows himself to be a great ironist. He also repeatedly emphasizes that a marriage should be based on friendship and gives his disgust at the usual “convention marriage [s]” (Bf. to Carl von Gersdorff from 15.04.1876) Expression. He is clearly looking for an educated woman and not a 'nice fool. '

18: Subsequent fragments 1881 16 [19].

19: Cf. I am dynamite.

20: Cf. Richard Wagner, Letter to Nietzsche v. 25/6/1872 & Letter to Nietzsche v. 24/10/1872.

21: The fact that he ignored it the first time implicitly follows from the fact that Wagner felt compelled to repeat the suggestion at all. However, in the surviving detailed letter of response to this repeated suggestion, Nietzsche does not respond to this offer with any syllable, as if he had “read over” it (cf. Letter to Richard Wagner from mid-nov. 1872, No. 274).

22: Classic and Romantic Mythology in the (Re) Birthing of Nietzsche's Zarathustra, p. 41. Trans. P.S.

23: In this regard, see Diethe, Forget the whip And also the corresponding chapters in Paul Stephan, Left-Nietzscheanism.

24:Aph 94.

25: From old and new boards, paragraph 12.

26: In general, there is Zarathustra The Ideal of Marriage as a Symbiosis in Order to Realize the Child Together as a Project of Joint “Self-Overcoming” (cf. in particular the speech Of Child and Marriage).

27: See in particular the key speeches Of the three transformations and Of the virtuous.

28: See his rather skeptical considerations in Human, all-too-human, Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, Aph 265.

29: See as a preface to Animal Farm Drafted text Freedom of the press (Link to original).

30: Cf. The publisher's website.

32: None other than Simone de Beauvoir cites this passage, for example, to underpin her constructivist position in The Other Sex (cf. Left-Nietzscheanism, Vol. 2, p. 354) and Judith Butler also repeatedly refers to Nietzsche in her radical constructivism (see ibid., pp. 473-478). Feminisms of all varieties can be recognized in Nietzsche's writings. (See also ibid., Vol. 1, pp. 50-55.) The strange thing about Nietzsche's sometimes essentialist statements on the subject of “man and woman” is precisely that they are in obvious opposition to his basic anti-essentialism — and he knows this when he, for example, In Beyond Good and Evil Underlines that these views are”My Truths” acts (Aph 231).

33: In this regard, see Stephen in detail, “Don't forget the whip! ”.

34: Just think of the relevant reports from people who have undergone appropriate hormone therapy.

35: Poems 1895 to 1910, P. 72.