Female Barbarians — When Women Become a Threat

Female Barbarians — When Women Become a Threat

In today's world, which wants to call itself modern and equal, old patterns continue to have an effect — rivalry instead of solidarity, adaptation instead of departure. The essay provocatively asks: Where are the barbarians of the 21st century? It shows the emergence of a new female force — a woman who does not destroy but refuses, who evades old roles and gains creative power from pain. Through examples from reality and literature, the text attempts to show that true change does not start in obedience but in bold “no” — and that solidarity among women could be the real revolution.

We awarded this text second place in this year's Kingfisher Award for Radical Essay Writing (link).

If you'd rather listen to it, you'll also find it read by Caroline Will on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy's YouTube channel (link) or on Soundcloud (link).

I. Introduction

When I finished my studies over twenty years ago, I felt that our time had come. “It's our turn now, girls! “I thought enthusiastically. Educated, courageous and strong, we wanted to create a new reality in which women no longer just play a supporting role, but are creators of their own lives. It seemed to me that all limits of my imagination and possibilities were open.

However, the reality proved to be more complex. Yes, that's right, we women are much more present today than was the case, for example, in the 20th century. There are numerous impressive examples in politics, culture and science. We hold high office, fight bolder for our rights, take to the streets to demonstrate. However, under the surface of emancipatory successes, old structures persist. Social expectations of women — to be perfect workers, mothers and carers at the same time — have not disappeared. There is still a discrepancy between women and men's worlds: qualities that are admired in men (strength, ambition, independence) are often viewed negatively by women. This creates an area of tension: On the one hand, women should be emancipated and self-confident, but on the other hand they should continue to fulfill traditional ideas.

In my opinion, the problem with us women lies in the lack of solidarity with one another. Women were not always brought up in a spirit of community, but rather in a spirit of rivalry and competition, in a constant struggle for recognition and acceptance in a patriarchal world. Yet it is precisely the community that opens up the opportunity to overcome individual weaknesses, release new forces and permanently shift existing power relations.

All too often, we act alone, repeating patterns of rivalry imposed on us. Anyone who only fights against each other weakens their own position and prevents the development of a solidarity movement. On the other hand, the experience of real community — sharing knowledge, strengthening each other, breaking up competition — is our greatest resource. Our greatest strength lies precisely in the experience of the community.

Hence the question: “Where are the barbarians of the 21st century? ”. Can the modern woman become a figure that Nietzsche described as a “barbarian” — not as a destructive force, but as a creative force that breaks old orders in order to make room for new things?

Perhaps this means that the woman of today no longer thinks in the categories that were given to her but is developing her own forms of power, creativity, and community. In this form, women could actually become a historical force that not only demands equality but also redefines the foundations of cooperation.

II. Solidarity as a Force

History shows us that men have perfected the art of working together over centuries. Armies, brotherhoods, trade unions—all of this was based on common goals, clear structures, and unwavering loyalty to the group. Women, on the other hand, mostly acted as individuals in a family environment. We were never really taught that we could achieve more together, that cohesion is not just a virtue but a survival strategy.

But it is precisely this insight that marks a turning point. It is only in community that we discover our true strength. What is a burden in solitude is shared by many shoulders and is therefore borne. What alone sounds like a soft whisper becomes a voice in the community that no one can ignore. Solidarity among women means leaving old patterns of rivalry behind in order to create new order. It is not about imitating men, but about developing your own forms of cooperation — characterized by empathy, creativity and mutual strengthening.

III. Nietzsche and the Figure of the Barbarian

Friedrich Nietzsche used the term “barbarian” in a sense that deviated far from everyday understanding. He did not mean a primitive, wild person, but someone who has the power to exceed the limits of old morality. For him, the barbarian was a creative figure — someone who was not afraid to destroy the existing order in order to make room for new values.

Nietzsche saw barbarians as the answer to modern nihilism. When old value systems fall apart, people are needed who have the courage to venture into the unknown and make sense of the world from the ground up. The barbarian is therefore not a destroyer out of hate, but someone who creates space for the future through refusal and rebellion.

Nietzsche wrote about this in masculine categories — his language is full of figures of warriors and “supermen.” He is often ironic about women, sometimes even misogynous. And yet Nietzsche can be read “against him” and see that his category of barbarian is gender-neutral. It is not gender, but inner strength and authenticity that determine the ability to create new values.

In this reading, the figure of the barbarian — or rather: the female barbarian, the Barbarin — turns into to a symbol of transformation. It embodies the power not only to be part of a story, but to write history yourself.

IV. A Woman — The Barbarin

If we regard the barbarian as a figure of creative refusal, then it is precisely the modern woman who represents a figure of the Barbarin.

For centuries, it was pushed to the margins of patriarchal culture — an edge that enabled exclusion and resistance at the same time. From there, she could not only observe but also learn a new way to question the entire system.

Their “barbarism” consists not of violence, but of refusing to accept roles that silence them. The refusal to adapt to the system that considers them “inferior.” Refusal to smile when obedience is required In refusing to accept the rules of a game she never invented.

A Barbarin is a woman who refuses to be a “better version of a man.” She doesn't play by foreign rules. She doesn't want to be material in someone else's project, but writes her own rules. Their strength comes from pain — from the experience of betrayal, loss, violence and is transformed into the decision not to give up and break through old addictions. She cuts through the old addictions, like a warrior who breaks her shackles. It has a trace of the “outside” — and it is precisely from this that it draws its creative power.

V. Women in the Mafia World

In Alex Perry's novel The Good Mothers Let's get to know the stories of women who are connected to the Calabrian mafia “Ndrangheta”. There, men — fathers, brothers, partners — are not romantic warriors, but cold, organized criminals. In the name of “honor” and “loyalty,” they torture, murder, and destroy the lives of their own families. In this system, the woman should only be a cog in the wheel: obedient, silent, submissive. But it is precisely in this machinery that the cracks occur.

Women like Lea Garofalo, Maria Concetta Cacciola, and others are starting to say “no.” Their resistance is not a heroic pose, but is born of sheer despair. They betray the clans, break the vow of silence, they turn to the state, knowing that this amounts to a death sentence.

In a world where silence means survival, her “voice” becomes the most dangerous weapon. It is an act of creative destruction — genuine barbarism against a sick system.

They have no army, no money, and no power. They only have their word, their refusal, their resistance. Their “no” becomes an act of creative destruction: barbarism based not on blood but on refusal. And that turns out to be stronger than the entire mafia clan. The tragedy is that many of them pay the highest price. But their betrayal is also a departure — a sign that even in a system that requires total control, a break is possible.

Their opposition proves that the biggest threat to the mafia does not come from outside — not from the police or politics, but from the voices of those who have been kept silent for years.

VI. Margaret Atwood's Gilead

Margaret Atwood paints a similar picture — albeit in literary form — in her novels The Handmaid's Tale and The Testaments. Gilead is a totalitarian utopia in which women are reduced to their functions: mother, servant, object of a ritual. Without name, language and freedom, all maids should be available to “redefine” humanity in the project of male rule.

But the first resistance does not come from weapons, but from refusal. June, Emily, Moira — initially intimidated — discover that true strength lies in community. Whispered words, furtive looks, solidarity become the beginning of a revolution. In this sense, their sisterhood is a modern form of barbarism: based not on dominance but on solidarity and a refusal to participate in lying.

Atwood's picture makes it clear that barbarism here is not brute force, but the creative power to escape, to reunite, not to be broken. Gilead thus shows that even in a seemingly total system — in which women are reduced to symbols, fixated on roles, trained for submission — the departure remains possible. Every refusal, every transmission of hope is an attack on the old order. The solidarity of the oppressed becomes a weapon. The “Barbarin” in Gilead is therefore the one who not only survives, but also transforms survival into resistance — and thus opens up space for another future.

VII. Barbarism as a Refusal

The figure of the barbarian of today is not a figure of the warrior with the sword. He doesn't come from outside to break down walls and plunder cities. He is someone who says “no” from within to an order that destroys him. He is an inner figure, a troublemaker who lives in the midst of order — and yet says “no” to a civilization that devours him.

The barbarism of the 21st century is a subtle art of refusal: the refusal to obey, the refusal to live by others' scripts. The refusal to allow yourself to be squeezed into roles that only serve to keep the system stable.

We don't need another utopia today. We need the courage not to serve as raw material for other people's projects. The barbarian is no longer the conqueror but the refuser, someone who says: today? No thanks!

VIII. Personal Perspective

I was born in communist Poland at the end of the 1970s. Women were everywhere — in the fields, in offices, sometimes in politics. They seemed irreplaceable in my childhood. Everyday heroines.

After years, I realized how stuck in old patterns we were. We shouted slogans during demonstrations, but in everyday life we rarely crossed the threshold of real resistance. We still chose the “known evil” instead of taking the risk of building something new. We obeyed instead of refusing.

Today I see that women who have experienced pain have the greatest strength: betrayal, abortion, poverty, violence. They are the ones who can get up again after the hundredth fall. It is they who no longer seek dependency, but choose to refuse. They are the real Barbarinnen — the ones who refuse to participate in the system that is based on complete adjustment.

IX. Conclusions

So where are the barbarians of the 21st century? There are no longer foreign male warriors at the gates, but women who refuse to participate in the old dancing from within. It is they who are on the sidelines and have the power to destroy the foundations of the system. Not through violence, but through refusal, through solidarity, through community.

Barbarism today is not the end of civilization, but the possibility of a new beginning. It is the “no” that becomes the language of freedom. It is the courage not to choose the known evil, but to step into darkness and create something new there — together.

Perhaps this is precisely the paradoxical truth of our time: Women who for centuries have been marginalized, treated as “inferior,” forced into invisibility, are today the only ones who have the courage to be “Barbarinnen.”

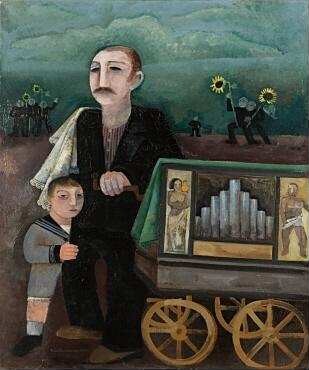

The article image is titled "Barbarin of the 21st century" and was painted by the author herself (painting, acrylic/oil). She herself writes: “The Barbarin of the 21st century does not ask for permission and does not justify herself. Born out of civilizational fatigue, it bears a break — between what is human and what eludes civilization. Her face is a map of modern emotions: anger, irony, tenderness and pain merge into a mask that reveals rather than conceals. It does not look into the past but through us, destroys illusions of harmony and shows that beauty comes from courage and not from order. The figure is not a portrait but a mirror. ”

Olimpia Smolenska was born in 1976 in Zielona Góra, Poland. At the age of seventeen, she went to Neuzelle in Brandenburg to complete her Abitur at a German-Polish grammar school. She completed her diploma in cultural studies at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder) in 2010 with a thesis on the topic Integration via language — taking into account the second language acquisition of Polish high school students in Neuzelle, Brandenburg. She currently works at Goethe University in the office of the Institute of Philosophy.

Literature

Atwood, Margaret: The Handmaid's Tale. Toronto 1985.

Atwood, Margaret: The Witnesses. Toronto 2019.

Perry, Alex: The Good Mothers. The Story of the Three Women Who Took on the World's Most Powerful Mafia. New York 2018.