#

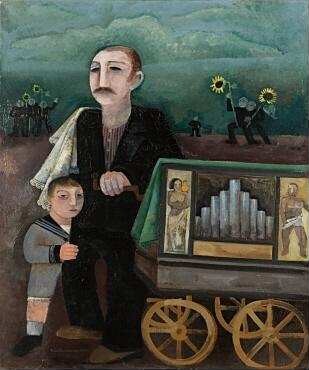

Carl von Gersdorff

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Being a Father with Nietzsche

A Conversation between Henry Holland and Paul Stephan

Nietzsche certainly did not have any children and is also not particularly friendly about the subject of fatherhood in his work. For him, the free spirit is a childless man; raising children is the task of women. At the same time, he repeatedly uses the child as a metaphor for the liberated spirit, as an anticipation of the Übermensch. Is he perhaps able to inspire today's fathers after all? And can you be a father and a Nietzschean at the same time? Henry Holland and Paul Stephan, both fathers, discussed this question.

We also published the complete, unabridged discussion on the Halcyonic Association for Radical Philosophy YouTube channel (Part 1, part 2).

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche‘s Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche's Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Last week, Emma Schunack reported on this year's annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society on the topic Nietzsche's technologies (link). In addition, in his article this week, Paul Stephan explores how Nietzsche uses the machine as a metaphor. The findings of his philological deep drilling through Nietzsche's writings: While in his early writings he builds on Romantic machine criticism and describes the machine as a threat to humanity and authenticity, from 1875, initially in his letters, a surprising turn takes place. Even though Nietzsche still occasionally builds on the old opposition of man and machine, he now initially describes himself as a machine and finally even advocates a fusion up to the identification of subject and apparatus, thinks becoming oneself as becoming a machine. This is due to Nietzsche's gradual general departure from the humanist ideals of his early and middle creative period and the increasing “obscuration” of his thinking — not least the discovery of the idea of “eternal return.” A critique of the capitalist social machine becomes its radical affirmation — amor fati as amor machinae.

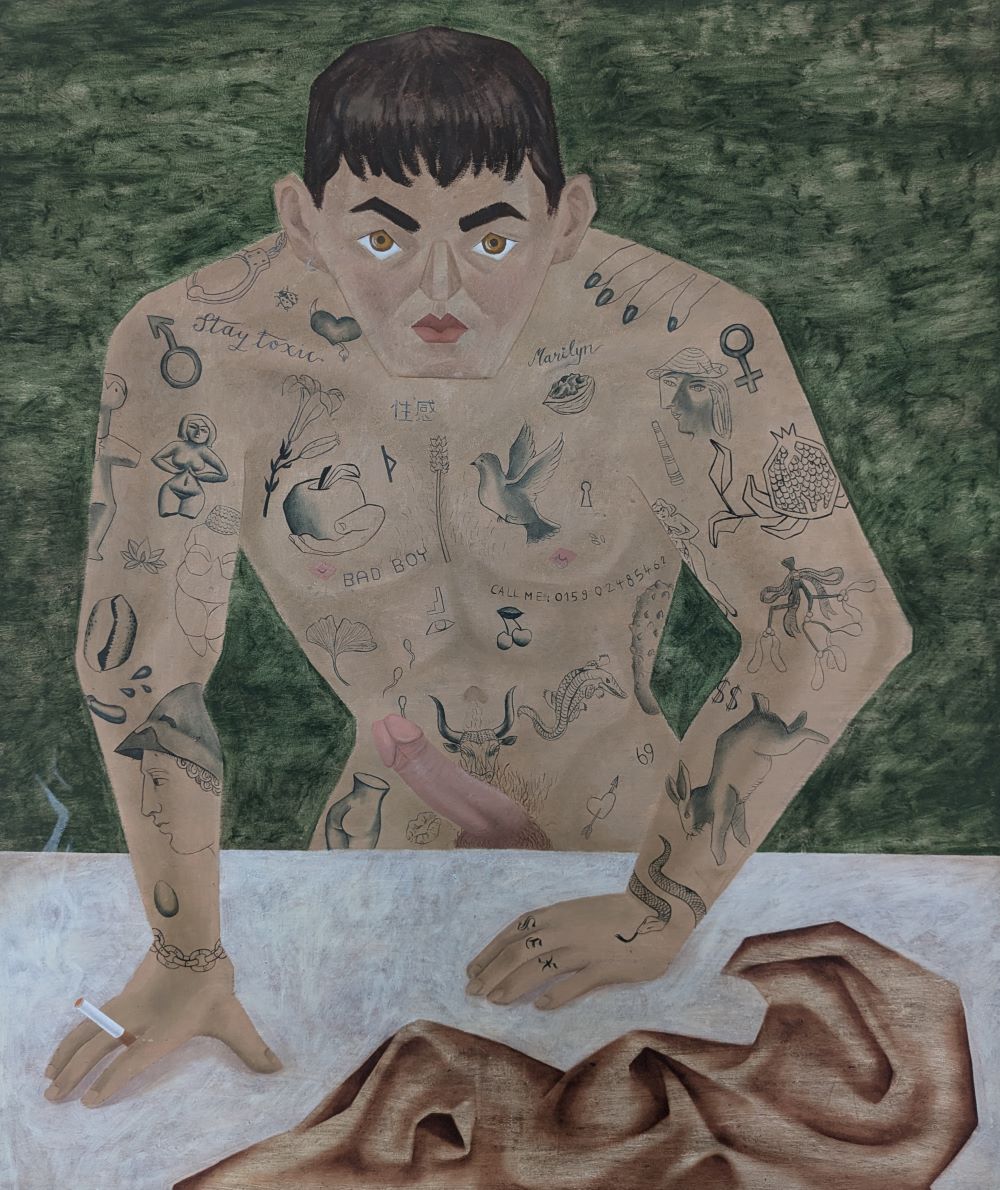

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

It is well known that Nietzsche had a hard time with women. His sexual orientation and activity are still riddled with mystery and speculation today. Time and again, this question inspired artists of both genders to create provocatively mocking representations. Can he possibly be described as an “incel”? As an involuntary bachelor, in the spirit of today's debate about the misogynistic “incel movement”? Christian Saehrendt explores this question and tries to shed light on Nietzsche's complicated relationship with the “second sex.”

The Educator’s Mark

Schopenhauer's Omnipresence in Nietzsche's Philosophy I

The Educator’s Mark

The Omnipresence of Schopenhauer in Nietzsche’s Philosophy I

It is no secret that one of Nietzsche’s most important philosophical references was the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860). That’s reason enough to trace the history of Nietzsche’s reception of Schopenhauer in a two-part article. In the first part, Schopenhauer scholar Tom Bildstein examines how the young Leipzig philology student Nietzsche was first inspired by Schopenhauer’s magnum opus The World as Will and Representation (1818), only to turn into a harsh critic of the Frankfurt “sourpuss” within a few years. — Link to part 2.