Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

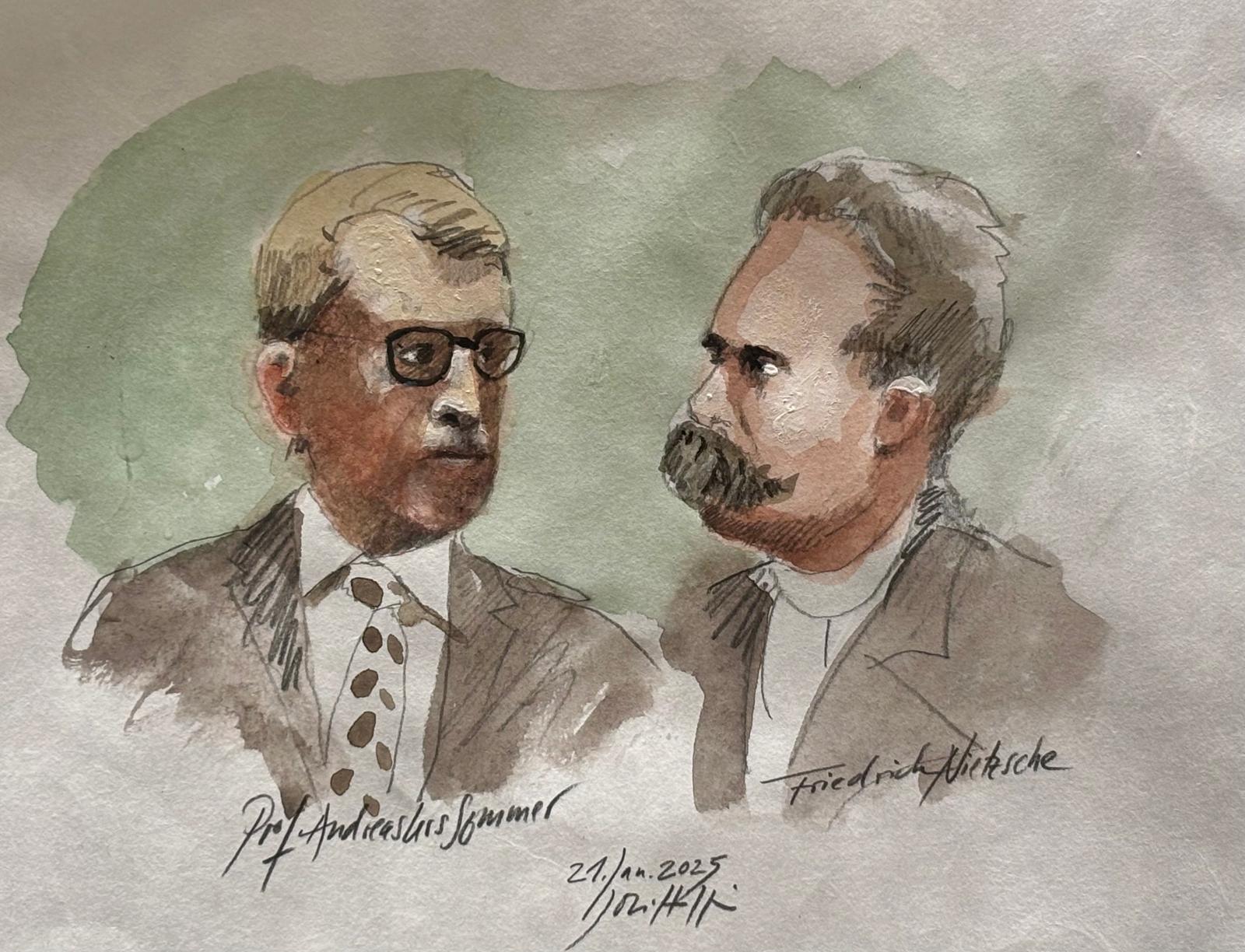

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Turning Moral Weakness Into Power

Nietzsche and the Accusation of Resentment

Strangers seem creepy to many. They immediately fear that these strangers will harm them. Many decent earners think that recipients of citizen benefits are lazy and therefore do not allow them to receive government support. To many educated people, illiterate people appear rude and simple-minded, with whom they therefore want as little as possible nothing to do with, whom they do not trust. Religious people are often afraid of atheists, who in turn are afraid of contact with religion. What you don't know often appears to be dangerous and you prematurely discount that. Such prejudices lead to rejection, which often solidifies to such an extent that counterarguments are no longer even heard. This is resentment that has existed for a long time, but which today makes consensus almost impossible in many political and social debates. This can degenerate into hate and contempt and then into violence whether between rich and poor, right and left, machos and feminists, abortion opponents and abortion advocates, vegetarians and meat-eaters. When one side prevails, it imposes its values on the other, and the resentment even becomes creative. In any case, it prevents you from making an effort to understand the other person. For Nietzsche, resentment has been driving the dispute over what is morally necessary for a long time.

“Resentment” is one of the key terms of Nietzsche's late work. The philosopher is referring to an internalized and solidified affect of revenge, which leads to the development of an overall negative approach to the world. Especially in On the genealogy of morality Nietzsche is trying to show that the entire European culture since the rise of Christianity has been based on this affect. Judaism and Christianity, in their hatred of aristocrats, propagated an ethics of the weak — in this act, resentment became creative. With a new creative ethic, Nietzsche now wants to contribute to a renewed revaluation of values in order to return to a life-affirming aristocratic ethic of the “strong.” In this article, Hans-Martin Schönherr-Mann introduces Nietzsche's reflections on resentment and works out what makes the accusation of mutual resentment so popular to this day.

Since the beginning of modernism in the 18th century, which entailed the dissolution of a uniform Christian approach to the world, the affected European societies have been in a permanent conflict of ideologies and worldviews. The French philosopher Paul Ricœur speaks of a war of interpretations, more precisely a “conflict of rival hermeneutics.”1. In such a situation, resentment makes a career. Because you cannot refute other concepts of the world because they are based on different premises, you often reject them with an emotional intensity that precludes a mutual effort to understand the other person from the outset. This is how resentment quickly builds up on each other.

I. Resentment in today's war of ideologies

The accusation of resentment really took off because the Enlightenment in the 18th century, with its demand for human rights, propagated the idea of seeing people as legally equal. Social equality was added a century later. Both ideas of equality remain unfulfilled to this day. Jürgen Grosse remarks: “A sense of resentment and the concept of resentment are increasingly connoted with questions of social justice, in particular with a frustrated desire for equality. ”2

As a result, people see themselves socially and politically disappointed. Capitalist and conservative views of the world prevent equality, which leads to aversions and political conflicts from a left-wing perspective, so that many feel socially disadvantaged. Max Hartung writes: “There is always a dialectic within the story: the guilty conscience of the hearers and the external determination through the law, the subtle spirals of power and the subjects included in them, driven by resentment without their knowledge.”3.

While in the first half of the 20th century, right-wing and fascist ideologies dominated in many countries and aggressively pursued liberal and left-wing thinking with terror, today's representatives of such worldviews see themselves marginalized, although they have received strong impetus in recent decades. Oliver Nachtwey notes: “Material and cultural status fears are drivers of resentment, negative affects, identitary closure and conspiracy theories — aspects that were identified early on as signs of authoritarian personality structures. ”4

II. Nietzsche's fabulous true world

Nietzsche developed his concept of resentment in a more focused and differentiated way. He was one of the first to recognize that as a result of the war of ideologies, there is no longer a single reality; rather, these are just different interpretations that cannot refute each other. He writes: “We have abolished the real world: what world was left? The apparent one maybe? .. But no! With the real world, we have also abolished the apparent world! ”5

For Nietzsche, the real world has thus become a fable. For this reason, the various views of the world can only be met with rejection, which cannot be justified, except through an enemy image or mutual resentment.

Scientism is now trying to overcome this dilemma with a scientific view of the world. But the sciences do not escape the problem of the difference between language and the world, nor their dependence on methods and the subjectivity of all perception, which cannot be undermined by intersubjectivity. Nietzsche's verdict of the fabulous true world therefore persists.

III. Resentment of the weak towards the strong

For Nietzsche, resentment is not due to a war of ideologies. Rather, it has a more far-reaching origin. Basically, it originates from the conflict between rich and poor back in ancient times. For Nietzsche, however, this is first conveyed by the Jewish priests. He writes: “The very big haters in world history have always been priests, even the most witty haters: — against the spirit of priestly revenge, all the rest of the spirit is barely considered at all. ”6

According to Nietzsche, the priests hated the aristocracy, i.e. the strong and rich, because they were inferior to them. Out of their feeling of inferiority and powerlessness, they developed a reluctance towards them, the resentment from which they took revenge on the aristocracy.

But how did they take revenge? By devaluing their ethical values and replacing them with the values of the poor. Are the latter not always the natural ethical orientations? Not at all, as Nietzsche points out: “They took the Werth, this “value” as a given, as in fact, as beyond all questioning”7.

But only Christianity gave this impression. Originally — i.e. before Judaism and Christianity — ethical goodness was not linked to the poor and weak; it did not originate from their need for help. For Nietzsche, it had a completely different origin when he wrote:

The pathos of nobility and detachment, [...] the lasting and dominating overall and basic feeling of a higher dominant species in relation to a lower species, to a “bottom” — That is the origin of the contrast between “good” and “bad.” [...] It is because of this origin that the word “good” is quite clear from the outset not necessarily linked to “unselfish” actions [.]8

This can be proven by Plato, for whom justice means “that everyone does his own thing. ”9 Good, even ethically good, is to fulfill its nature. If this has made you a craftsman, he should not try to interfere in the business of the powerful and rich. Of course, wealth means nobility and represents ethical goodness. Poverty, on the other hand, is ethically bad and tends towards malice.

IV. The revaluation of all values

According to Nietzsche, it was precisely this relationship that the Jewish priests reversed

who dared to turn back against the aristocratic equation of values (good = noble = powerful = beautiful = happy = loved God) with a terrifying consistency and held on with the teeth of the most profound hate (the hate of powerlessness), namely “the wretched are only the good, the poor, the powerless, the lowly are only the good, the suffering, the sacrificing, the deprived, Sick, ugly people are also the only pious, the only godly ones, there is bliss for them alone — but you, you who are powerful and powerful, are in all Eternally the wicked, the cruel, the lustful, the insatiable, the wicked, you will also be the unfortunate, cursed and damned forever! ”10

It is doubtful whether Nietzsche adequately describes the religious world of Judaism before the beginning of Christianity. The ancient religions, i.e. their priestly representatives, who generally served the rulers, thus participated in power and thus also in wealth. But Nietzsche goes on to refer to Christianity, which was originally a Jewish sect. How does Agnes Heller write: “Jesus was not a Christian, nor was he, of course, a European. ”11

It therefore seems more obvious to associate this revaluation of values, the devaluation of aristocratic morality and the appreciation of the ethics of the weak primarily with Christians, at least in view of their beginnings. As a result, resentment is primarily due to Christians, who also welcomed the poor into their ranks and who were unable to collaborate with political powers during their beginnings, as they were persecuted in parts of the Roman Empire because they carried out missions, which was forbidden to all cults. Nietzsche also continues: “You know who inherited this Jewish transformation. I recall [...] the sentence [...] — that is to say with the Jews The slave revolt in morality starts”12, but which Christians fought successfully to the end in order to interpret and change the world in a sustainable way with a new structure of ethics.

V. Resentment as a creative force

But didn't they leave everything as it was? Because Max Weber will then ask himself how a religion oriented towards poverty could achieve such a development of power and splendor as was felt particularly in Rome at the time. His answer was “due to unplanned side effects.”13, according to his biographer Jürgen Kaube: The monks' poverty rule in monasteries led to the accumulation of immense wealth.

With the moral turn of elevating poverty and weakness to high virtues, while wealth and power are viewed skeptically, and humility takes the place of pride, Christians not only completed the revaluation of all values. Instead, they devalued life itself for Nietzsche, but this resulted in new values. Nietzsche writes:

The morale of slave revolt begins with the fact that resentment becomes creative himself and gives birth to Werthe: [...]. While all noble morality grows out of a triumphant yes to themselves, slave morality says no from the outset to an “outside,” to an “other,” to a “not-self”: and this no is their creative fact.14

With this creativity of resentment, with this change from good to evil and from evil to good, Nietzsche no longer explains morality from himself, in a sense causally — the good from the good or as a story of good — but from its opposite, i.e. genealogically: Today's ethical good springs from evil, as the ancient aristocratic ethic of strength must appear to today's ethics. That is the meaning of Nietzsche's concept of genealogy.

Altruism thus represents ethical good, while egoism does not simply represent evil. Rather, he appears today as if he had nothing to do with ethics at all. Nietzsche, on the other hand, reveals this suppression of the origin of good precisely from this evil. He writes:

Rather, it only happens with a Decline aristocratic claims that this whole contrast “selfish” “unselfish” “unselfish” imposes itself more and more on the human conscience — it is to use my language that Army Instinct, who finally spoke with him (also to Worten) comes. [...] ([...] today there is a prejudice which takes “moral”, “unselfish”, “désintéressé” as equivalent terms, already with the violence of a “fixed idea” and head illness).15

VI. Egoism instead of altruism

Nietzsche, on the other hand, does not want to be an altruist. For him, Socrates's concept of suffering wrong rather than doing wrong is hostile to life and paves the way for the Nazarene commandment, according to which one should love one's enemies. Instead, Nietzsche invokes Buddhism and in its sense propagates egoism, which represents almost the highest immorality for Christian morality and rational ethics following Kant. Buddhism on the other hand

resists nothing more than the feeling of revenge, aversion, resentment [...]. <er>The mental fatigue that he finds, and which is expressed in too great “objectivity” (i.e. weakening of individual interest, loss of heavyweight, of “egoism”), combats with a strict return of even the most spiritual interests to persona. In Buddha's teaching, egoism becomes a duty [.]16

So Zarathustra spoke in the same sense, “that his word the selfishness Blessed, the healthy, healthy selfishness that springs from a powerful soul. ”17

Only egoism does not develop resentment that Nietzsche does not need, because it is initially transformed as self-loathing into the overwhelming Christian love of one's neighbour, the pure will to power the weak. Because anyone who refuses to do so is an evil sinner, on whom resentment is directed, as at the beginnings of Judaism at the aristocrats. As a result of this revaluation of values, resentment has become creative.

The question is, of course, whether egoism is similarly animated by resentment. Nietzsche himself hates Christianity and the “last people”18who turn away from Christianity materialistically: socialists and liberals. Out of egoism and in differentiation from all traditional morality, Zarathustra create new values that push people beyond themselves. Does this not make resentment even more creative? Nietzsche wants to be creative, but medieval Christianity doesn't. In any case, it is a further revaluation of the values that Nietzsche propagates, whether driven by resentment or not.

VII. Accusing each other of resentment

Max Scheler also accuses Nietzsche of resentment towards Christianity. For Nietzsche devalues the highest value, namely the sacred. Nietzsche is not alone for Scheler when he writes: “We believe [...] that the core of bourgeois morality, which began to replace Christians more and more from the 13th century until they achieved their highest achievement in the French Revolution, It is rooted in resentment. ” 19

In a sense, however, he is not so distant from Nietzsche if he accuses his contemporaries not only of materialism. Instead, for Scheler, this devaluation of Christianity is driven by people who lack morality. He writes:

In a sense, however, he is not so distant from Nietzsche if he accuses his contemporaries not only of materialism. Instead, for Scheler, this devaluation of Christianity is driven by people who lack morality. He writes:

There is perhaps no point on which the insightful and well-intentioned of our time are more united than that: that in the development of modern civilization, things [...] Man's Lord and Master have become; [...]. But far too little is it realized that this universally recognized fact is a consequence of a fundamental An overthrow of appreciation is who has its root in the victory of the value judgments of the most vital lowest, [...] and the Resentment is its root is!20

Nietzsche could also formulate the last two half sentences in a similar way. Of course, Scheler Nietzsche would just be one of these “deepest” ones. But just as Nietzsche sees Christians as weak and driven by resentment, Scheler, conversely, regards the enemies of Christianity as such weak. With Nietzsche, they would then have to creatively assert themselves as Christians once did against the aristocrats, not for Scheler, of course.

Sartre, however, would agree with Nietzsche if he did not understand the anti-colonialist struggle, as promoted by Frantz Fanon, as a resentful reaction of the colonized people against their colonizers. Rather, he writes: “As <Fanon>proven, this irrepressible violence is not an absurd storm, not even the resurgence of wild instincts, not even the effect of resentment: it is nothing more than the new person who creates himself. ”21

Here you could hear a reference to Nietzsche's superman in the background; there are interpretations not only in existentialism but also in post-structuralism that draw the proletarian or anti-colonial revolutionary in this direction.

Gabriel Marcel, on the other hand, criticizes the existentialist self-image from an emphatically Christian perspective, as Sartre did, for example, in his novel Maturity period designs. Marcel writes:

And how did you want to prevent this from simulating or parody autarkiaWhich (the human being) gives himself up, degenerates into repressed resentment against himself and results in the techniques of humiliation? There is an obvious path that leads from abortions, where Sartre's customers come and go, to death camps, where torturers pounce on people who are unable to defend themselves.22

Historically, this is probably the first comparison of abortions with the Holocaust, a heavy gun that thus speaks of tremendous resentment.

Hannah Arendt, in any case, protected Nietzsche from every accusation of anti-Semitism and from any resentment towards Judaism when she wrote in 1951, when Nietzsche was still the ancestor of the Nazis for many:

[U] and finally Friedrich Nietzsche, whose so frequently misunderstood remarks on the Jewish question are consistently based on concern for “good Europeanism” and whose assessment of Jews in the intellectual life of his time is therefore so surprisingly fair, free from resentment, enthusiasm and cheap philo-Semitism.23

Item image source

Francisco de Goya: The seesaw (1791/92) (spring)

sources

Arendt, Hannah: Elements and origins of total domination (1951), 9th edition Munich 2003.

Große, Jürgen: The cold rage. Resentment theory and practice. Marburg 2024.

Hartung, Max: Revolution? Revolt? Resistance! Change and how it can be thought of in the work of Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault. Munich 2015 (link).

Brighter, Agnes, The resurrection of the Jewish Jesus (2000). Berlin & Vienna 2002.

Kaube, Jürgen: Max Weber. A life between the ages. Berlin 2014.

Marcel, Gabriel: The Humiliation of Man (1951). Frankfurt am Main 1957.

Nachtwey, Oliver: De-civilization. About regressive tendencies in western societies. In: Heinrich Geiselberger (ed.): The big regression. An international debate on the spiritual situation of the time. Berlin 2017, pp. 215—232.

Plato, Politeia (c. 374 BC), transl. by Friedrich Schleiermacher, works Vol. 3. Hamburg 1958.

Ricoeur, Paul: Hermeneutics and structuralism. The conflict of interpretations I (1969), Munich 1973.

Sartre, Jean-Paul: The period of maturity (1945), Collected works novels and stories Vol. 2 Reinbek b. Hamburg 1987.

Sartre, Jean-Paul: preface to: Frantz Fanon, The Damned of this Earth (1961). Reinbek near Hamburg 1969.

Scheler, Max: Resentment in building morals (1912). In: Ders. : On the overthrow of values. Treatises and essays (1915/1919), Collected works Vol. 3, 4th ed. Bern 1955.

footnotes

1: Hermeneutics and structuralism I, P. 30.

2: The Cold Rage, P. 327.

3: Revolution? Revolt? Resistance!, P. 242.

4: De-Civilization, P. 228.

5: Götzen-Dämmerung, Like the “real world” ...

6: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 7.

7: On the genealogy of morality, Preface 6.

8: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 2.

9: Politeia, 433 a.

10: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 7.

11: The resurrection of the Jewish Jesus, P. 88.

12: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 7.

13: Max Weber — Ein Leben zwischen den Era, P. 143.

14: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 10.

15: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 2.

16: The Antichrist, 20.

17: So Zarathustra spoke, Of the three bad guys, paragraph 2.

18: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, paragraph 5.

19: Resentment in building morals, P. 70.

20: Ibid., P. 145.

21: preface to: Frantz Fanon, The Damned of this Earth P. 18.

22: The humiliation of man, P. 157.

23: elements and origins of total domination, P. 72.

.jpg)