The Monkeys Dance Inexplicably. Nietzsche and Contemporary Dance Culture

Reflection, Movement, Misery

The monkeys dance inexplicably. Nietzsche and contemporary dance culture

reflection, movement, misery

In addition to hiking, dancing is one of the most prominent soldiers in Nietzsche's “moving [m] army of metaphors, metonymies, anthropomorphisms.” Based on Nietzsche's reflections on the art of movement, Jonas Pohler explores the paramount importance that it plays in our present day. Is the effect of dance primarily sexual? What does dance have to do with technology? What symbolism is the dancing gesture able to convey?

Just no fuss. Dancing and intellectual reflection, they seem to be mutually exclusive. No one will dispute the claim that philosophical and technical ideas are the last thing that makes you a good dancer — but is that so? “The Germans are too clumsy,” postulated an acquaintance with whom I spoke about the topic. Nietzsche would probably have agreed to this. In an exceptionally beautiful aphorism, he wrote about the Germans' enjoyment of art:

When the German really gets into passion (and not just, as usual, in the goodwill to passion!) , he then behaves in the same way as he must, and no longer thinks about his behavior. But the truth is that he then behaves very clumsily and ugly and as if without tact and melody, so that the audience has their pain or their emotion and nothing more: — unlessthat he lifts himself up into the sublime and delighted, [...] — towards a better, lighter, southerner, sunnier world. And so their cramps are often just signs that they danse Would like: these poor bears, in which hidden nymphs and forest gods live their nature — and sometimes even higher deities!1

Is that the reason why the worse half of humanity is so often struggling and is plagued by complexes and discomfort? — That's another story...

I. Dancing on the Internet: Unmanageable Landscapes

The topic seems more timely than ever. This shows the omnipresence of dancing people on social media. Transmitted primarily from the USA, but also affected by it, from all over the world. You can see: “Humanity” is dancing. Anyone who delves a bit deeper into the subject matter comes across choreographies, performances and insights into dance studios; comes across “battles” with stimulating interjections. Movement takes on military form. — Nonsensical next to that: Twerken for the Salvation of Souls. Not a bad joke for many anymore.

The Internet is celebrating its K-pop stars such as the Bangtan Boys (BTS), founded in 2010, or the one born in 1996 Jennie Kim by the also South Korean band Black Pink. It is known from them that these subjects of the “idols” industry go through intensive dance training, which, of course, fairly shamelessly copies US music and dance style trends. American choreographers and record labels are probably working on the so-called “acts” at least around three corners. Dance instructors discipline their clients not only to perfection but also to express themselves freely. Their success undoubtedly speaks for a nerve that they immediately hit emotionally with a mostly female audience. The appearance is favorable, comprehensible everywhere and subject to hardly any social or socio-structural controls.

I can't hide that I was not unimpressed by some trends myself. For example, the dance performance of Disney star Jenna Ortega born in 2002 in the Netflix series Wednesday (2022), the song that dates back to Lady Gaga's at the time Bloody Mary (2011) and the words: “I tell them my religion's you [.] [...] We are not just art for Michelangelo to Carve/he can't rewrite the aggro off my furied heart”2How an alleged autistic woman who plays them dances.

Musically, although less dance-wise, the hype surrounding and early death of XXXTentacion with his sad electro ballad has also Moonlight Many are anything but left cold. Even the almost violent dance choreographies of Jade Chynoweth, the Viva Dance Dance Studio from South Korea, as well as King Kayak & Royal G's brute performance toward Oil it The Afrobeat star Mr. Killa or the very danceable Amapiano classic Adiwele by Young Stunna, in which “the flex,” i.e. the flaunted bragging, and dance seem to intertwine, compelled me some respect.

Unimaginable but true: Dance is advancing to The The form of expression and art of our decades and is perhaps even more, a sign of the anthropology of globalized capitalism. Its increasing importance is derived from various factors, with the most opaque and least edited probably being art, aesthetics, and philosophy.

Undoubtedly, one of his recipes for success is his general accessibility: What has a body can dance and does not require education or professional equipment. The second undeniable element, both for social media and for the advertising industry, in which we repeatedly see dancing bodies (admittedly with products that have nothing to do with it), lies in the fact or appearance of transmitting authentic emotions or affects — for the less subtle, sex and presumption.

Is that so? It's less banal than you might think. Who sexualizes or desexualizes? The hip swing is the symbol of human sexuality; only a stone could remain motionless. — Does the term “sex” even appear in Nietzsche, for example? — And yet a dance can be completely harmless, like an aphorism from Human, all-too-human shows how viewing a work of art produces an immediate surplus of pleasure. The text as a stimulant:

Books that teach dancing. — There are writers who, by presenting the impossible as possible and speaking of the moral and ingenious, as though both were just a whim, a desire, produce a feeling of excessive freedom, as if a person stood on the tips of his feet and had to dance for inner pleasure.2

Even though attempts are made again and again to dedovetail the dance, the solution is likely — as is so often the case — an ambivalent one. One thing is clear: When in doubt, you dance alone in the neoliberal Pleistocene. — Life is what you make it!

II. Technology, Dance and Pop Culture

Electronic music significantly changed dance behavior almost globally. In particular, the technical intensification of bass and the invention of the rhythm machine can be regarded as the most important and substantial interventions. These are technical innovations that reduce, ration and equalize — establish a mere relationship with the naked organic body, less an intellectual or cordial one, such as a symphony orchestra or band.

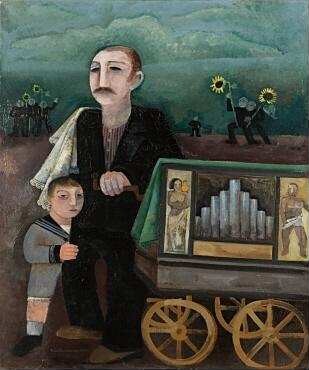

Nietzsche would probably have known more about this than he knew. The forms of illuminated cold crowds that we know from today's club culture with their electronic cult could not yet be known to him. The dance conventions of his time are only beginning to emancipate themselves. Ballroom dancing, folk dancing and ballet dominate the corresponding social fields. Mass culture and exotic pop greats such as Josephine Baker — although variety shows are already gaining in importance in the second half of the 19th century — are only just beginning to become emblems of an emerging popular cultural mass base. As far as I know, Nietzsche did not comment on the variety show.

He writes about Dionysia and Saturnalia, intoxication and theatre. He is looking for the anthropological, the instinctive, and the intense. Let's follow the Dionysian trail: The whole world a dance hall? A ballroom dance, going to work in the morning, then motionless like the stars in the sky and dancing yourself into bed in the evening? The world, the puzzle image of a dove? Dancing hall of the living? How could stars dance? — The well-known and already taunted Nietzsche quote about the chaotic celestial body is central in the Preface His Zarathustra — more specifically, his speech about the “last man.” Following this, the famous tightrope walker in an accident appears. The sentence explains internal chaos as a condition for achieving a highest ideal. The time is decisive: “Woe! There will come a time when humans will no longer give birth to a star. Woe! ”4

In the works published during their lifetime by digitized critical edition The root syllable “dance*” appears in just 69 of 3287 text sections, and only rarely in an explicitly analytical context. In Nietzsche's philosophical reflection, most prominent in the Birth of Tragedy:

Singing and dancing, people express themselves as members of a higher community: they have forgotten how to walk and speak and are on their way to flying up into the air dancing. His gestures speak of enchantment [...]. Man is no longer an artist, he has become a work of art: the artistic power of all nature, to the highest satisfaction of the original one, is revealed here under the showers of intoxication.5

The dance metaphor is less present in Nietzsche than many might assume, and as a whole probably coincides with the concept of “Dionysian,” the phrase for reflectless, irrational affirmation of life, the physical overcoming of thought:

In Dionysian Dithyrambus, man is stimulated to the highest increase of all his symbolic abilities; something sneezing is urged to express itself, the destruction of Maya's veil, oneness as the genius of the species, indeed of nature. Now the essence of nature should express itself symbolically; a new world of symbols is necessary, first of all the bodily symbolism, not just the symbolism of the mouth, the face, the word, but the full dance gesture that rhythmically moves all limbs. Then the other symbolic forces, those of music, in rhythm, dynamism and harmony, suddenly grow impetuously. In order to grasp this total unleashing of all symbolic forces, the human being must already have reached the level of self-alienation that wants to express itself symbolically in those forces: the Dithyrambic Dionysus servant is therefore only understood by his kind!6

III. Symbol of what? Talk for what?

Since we're talking about symbolism, we have to become semiological for a moment: What does a gesture, a movement mean? Decoding the string of an ordinary dance is extremely difficult, and its elements — like hardly any other encodings — are both anthropologically and culturally determined. Even on TikTok, every trend carries a gestural string that, even in frame-by-frame analysis, transports very unclear content, with the form of a social relationship among people appearing to be the most prominent dimension; for example, the practice of imitation or classification. The semiological problem is decisively linked to the immediate transitions, which we call movement, which, as in a symphony, separate the good dancer from the bad dancer. It is similar to the arrow paradox of Zenon of Elea, according to which a movement consists of an infinite number of points of standstill and is therefore questionable how it could even exist. In our case, it raises the problem of whether the individual gesture is the meaningful element of the dance or its change, without which dance as a movement would be impossible.

Nietzsche later put in Human, all-too-human this semiotic dimension is explicitly open:

Sign and language. — Imitating signs is older than language, which takes place involuntarily and now, with a general suppression of sign language and developed control of muscles, is so strong that we cannot look at a moving face without innervating our face [...]. The imitated gesture led the imitator back to the sensation it expressed in the face or body of the imitated person. This is how you learned to understand yourself: [...]. Conversely: Gestures of pleasure were themselves pleasurable and were therefore easily suitable for communicating understanding [...]. — As soon as you understood yourself in gestures, a symbolism of the gesture: I mean, you could communicate using a tone-sign language, so that you sound first and Sign (to which he added symbolically), later only produced the sound. — [...] [W] First the music, without explanatory dance and mimus (sign language), is empty sound, through long habituation to that juxtaposition of music and movement, the ear is schooled to immediately interpret the clay figures and finally reaches a level of quick understanding where the visible movement is no longer at all requires and the sound poet without the same understands. [...]7

Dance is therefore double-coded, self-referential. Behind the code is a code of the conventions of a corresponding media and social field. As far as the side of reflection is concerned, dance has two dimensions: freestyle and practiced movement. The great dancer probably has both, but is ultimately in line with the freestyle. Behind this is the idea of the talented genius who finds the form of a direct transistor just for the sake of expressing his feelings — Poetry of the movement. In addition, speculatively and in the spirit of Nietzsche, dance expresses the unspeakable in a different, visual and subjective code. A second well-known quote that shows this semiotic dimension of the body also comes from the first book ofthe Zarathustra. Nietzsche's prophet proclaims that he “would only believe in a god who knew how to dance.” Interestingly enough, from a passage that About reading and writing acts: “Of everything written, I only love what someone writes with his blood. [...] I hate reading idlers. [...] Another century of readers and — the spirit itself will stink. ”8

IV. Dancer, why can't you speak?

As you can see, there are a lot more questions here than answers. Perhaps reference may be made here recently to Elfriede Jelinek, who with her production A sport piece (1998) brought social movement organizations closer to fascism. There is certainly something to that, because as every good insurance agent knows: “The less you know, the better it sells.” Is this interpretation sustainable? As part of an increasing militarization of the social sphere, its effects can be seen in sports, the gym, and dance, which speaks its silent language and is not always understood. Deleuzes' control company in no way overcame Foucault's disciplinary society,9 But connects with it: Anyone who speaks of control society must ask who should give up the dancer's patron? It is clear who is disciplining him. The dancer wants his own lock, the drill, the authority of the dance teacher. But who controls? — The path leads back: It is the gaze again, the reflection. Because the view on social media is anonymous but gives its judgments automatically controlled by likes, shares, references by admirers and haters, it takes the form of a multi-eyed phantasm that could be described as “common will.”

Since this will is the least real and exists only as a collective and unsystematic, as a familiar implantation — as a supposedly necessary generalization of what dance is, should and can express, especially what it should look like — it presents itself as a protective mechanism against fear (the fear of loss of control), which is called the idealistic smaller or larger communities in their real body, dancing self-Feeling should protect, that is.

In short, the Argus Eye watches over the dancer, but by becoming his own eyeball. (Normal case of training and discipline.) Since it is no longer difficult to let go, the reflection is only suspended.

On the other hand, Nietzsche's cheerful dance songs, which most recipients probably didn't remember, were not among the strongest of modern poetry, incredibly romantic and innocent. So is Zarathustras Dance song Not really one — and The other dance song10 At the end of the third book, a negligible lyrical effusion anyway — but a small reflection on life, “a song of dancing and ridicule on the heavy mind”:

I looked in your eye recently, oh life! [...] [S] you laughed poettically when I called you unfathomable. “That is the speech of all fish, said you; what them It is unfathomable. [...] “[...] But when the dance was over and the girls had gone away, he became sad.11

Perhaps this idealization of dance is memorable and valuable for our consciousness in the end because it shows that it can also be different.

Jonas Pohler was born in Hanover in 1995. He studied German literature in Leipzig and completed his studies with a master's degree on “Theory of Expressionism and with Franz Werfel.” He now works in Leipzig as a language teacher and is involved in integration work.

Footnotes

1: The happy science, Aph 105.

2: “I'll tell them that you're my religion. [...] We're not just art — carving out for Michelangelo [/] — he can't describe the anger from my angry heart. ”

3: Human, all-too-human I, aph. 206.

4: So did Zarathustra speak, preface 5.

5: The birth of tragedy, Paragraph 1.

6: The birth of tragedy, paragraph 2.

7: Human all too human I, Aph 216.

8: So Zarathustra spoke of reading and writing.

9: Editor's note: In the text Postscript on the control companies Gilles Deleuze put forward in 1990 the thesis that what Foucault had described as “disciplinary societies” — i.e. societies such as the modern ones of the 18th, 19th and 20th century, in power is carried out primarily through individual methods of discipline (drill, training, education...) — had been replaced in his present by the type of “control society,” which is less about individually internalized discipline, but the technical based surveillance of the population to punish border crossings. This apparently entails greater scope for individual freedom, but in reality it is no less repressive.