A New Nietzsche Biography

In Conversation with Andreas Urs Sommer

A New Nietzsche Biography

In Conversation with Andreas Urs Sommer

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche died 125 years ago, on August 25, 1900. We are taking this important date as an opportunity to publish interviews with two of the most internationally renowned Nietzsche researchers, Andreas Urs Sommer and Werner Stegmaier, around this year's anniversary of his birth on October 15, 1844. Freiburg philosophy professor Sommer is currently working on an extensive biography of the thinker, which is why the conversation with him focused in particular on his life; the conversation with his colleague from Greifswald, which focuses primarily on Nietzsche's thinking, will follow shortly (link). It will soon become apparent that the two cannot be separated. Among other things, we asked the expert about Nietzsche's character, his sexuality and if he lived what he proclaimed.

I. From Commentary to Biography

Paul Stephan: Dear Professor Sommer, first of all, thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. It is hardly an understatement to call you one of the leading Nietzsche researchers of all. In addition to many other things, you are in particular the head of the Nietzsche Commentary Research Center at the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and have contributed several volumes to this important commentary yourself.1 Now you are venturing into a new major project, namely a new scientific biography of Nietzsche. Currently, we're starting this email dialogue on 4/4/2025, you're still working on it; by the time you publish this conversation, you'll probably have already completed it, if it hasn't even been published already. Even though you would be a worthy interlocutor on probably all aspects of Nietzsche's life, work and impact, this ongoing project should therefore become the main subject of this exchange.

My first question, which is addressed to you in this regard, may be a bit provocative, but it certainly won't surprise you. I would like to say that there is probably no other philosopher as there are as many biographies as about Nietzsche. In addition to countless popular science accounts of his life, the three-volume scientific biography of Curt Paul Janz has been available for many years — even offside topics such as Nietzsche's sexuality or his possible illness of syphilis have become the subject of extensive monographs. In which areas do you want to stand out from your predecessors? Where do you hope to be able to set new accents?

Andreas Urs Sommer: Unfortunately, I have to reduce the expectations that have now aroused a bit and thank you, dear Mr. Stephan, for the opportunity to interview him, even though his subject matter, the Nietzsche biography, has by no means been completed. It won't be the same even on Nietzsche's 181st birthday on 15/10/2025. In fact, the publisher — it is C. H. Beck in Munich — had originally agreed on a manuscript submission deadline at the end of last year, which I was unfortunately unable to meet due to the various other obligations you mentioned. The quarter-round anniversary of death should not be an occasion to rush with the book, which is supposed to have a hand and foot — and perhaps a few more body parts. C.H. Beck Verlag has kindly given me more time to think and write. Because we are in a very peculiar situation: On the one hand, the international research activities on Nietzsche are immense, and on the other hand, since the work of Curt Paul Janz, which you mention, no comprehensive Nietzsche biography has been published that would actually be drawn from current research. If you wanted to exaggerate it, you could say: Since 1978, all biographers have written off Janz, who has also diligently copied it himself: the first volume of his biography is based on Richard Blunck: Frederick Nietzsche. Childhood and youth from 1953 — a book that was actually finished in 1945 and still had to be denazified, as it was originally written in the Nazi haze.

In short: On the one hand, there is a rich wealth of recent research findings; on the other hand, they have never been synthetically cast into a generally readable biography. In addition, the biography will pursue a decidedly philosophical claim: It wants to encourage people to think.

PS: It is of course very understandable that you do not want to rush such a major project. Especially since Nietzsche also in the Preface to Morgenröthe writes: “Such a book, such a problem, is in no hurry; moreover, we are both friends of Lento, as well as I am my book. It is not for nothing that you were a philologist; you may still be, that is to say, a teacher of slow reading: — at last you also write slowly. ”2 Perhaps that would also be one of the lessons you could learn from Nietzsche? Not to be stressed by the demands of an overheated and hectic present and yourself seine Take time to learn, in accordance with the own Speed to live?

AUS: You can certainly include this advice in the recipe book of successful life — and Nietzsche would certainly have done it too, like many thinkers before him. Cheerful composure in the face of the supposedly super-urgent demands of the day should never be wrong. However, as an art of life oracle, Nietzsche is often just a caricature of himself, especially when you assign commonplaces to him. He himself did not follow the advice of slow reading — he read superficially, quickly, criss-cross and always focused on his own intellectual needs. Still to the advice of slow writing. He likes to describe how he — for example at So Zarathustra spoke — got into an eruptive writing frenzy.3 Readers with background knowledge often notice the breathlessness, even the hasty nature of his writing activities, while he then gets into “più lento” in phases. Nietzsche does not secrete a continuous flow of writing — he ticks wild when writing.

PS: Yes, Nietzsche repeatedly encounters a huge discrepancy between life and work, between the myth that Nietzsche especially in his supposed “autobiography” Ecce homo created around himself and which continues to be spun on and on to this day and for what he really was. How do you deal with this obvious contradiction when writing your biography? Is it even possible to go beyond the thicket of anecdotes and legends to an “authentic Nietzsche”? And does the established Nietzsche image have to be completely revised in some parts in the light of recent research? Is it time to finally apply Nietzsche's famous “hammer” to perhaps his most stubborn creation: the “Nietzsche brand”; the “idol” of himself that he and after him created his countless disciples and enemies?

AUS: Since he invented himself writing as a child and as a teenager, Nietzsche has been engaged in constant autobiographical self-reflection: We have countless testimonies about him in which he describes his life, even from very early times, when there was apparently no life at all to describe. The biographer is well advised to be suspicious of these personal testimonies — in particular of the parade horse in the stable of Nietzsche's autobiographical work complex, created in 1888 Ecce homo. This work is not simply an “autobiography,” but a text with a crystal-clear objective, namely to prepare the world for the destructive lightning of the “transformation of all values,” which Nietzsche wrote with The Antichrist Hoped to complete. Accordingly, there is pretty much the opposite of an accurate objective reflection of a life's journey. One should therefore not get on Nietzsche's autobiographical statements prematurely and simply take them at face value. Rather, it is always necessary to ask what the author intended with their placement. And fortunately, the biographer has a variety of other documents at his disposal which make it possible to contextualize these autobiographical statements. In general, contextualization is a central task of a Nietzsche biography. He is simply not the lonely thinker at a peak in the history of ideas, but is often intertwined and entangled with his time and with his contemporaries. Even my biography will not present “objectively” a “true Nietzsche.” But it tries to give a rich, differentiated picture.

II. Nietzsche as a Person — and His Sexuality

PS: How do you actually have to introduce yourself to Nietzsche as a person? In films such as the adaptation of the novel And Nietzsche cried by Irvin D. Yalom (USA 2007) or Lou Andreas-Salome (D/OE 2016) he is shown as a driven eccentric. In my own research, however, I repeatedly came across statements from third parties that portray him as rather polite and reserved. A common image of a “typical Nietzschean” would probably be a kind of Klaus Kinski4, who is peaceful at times, but then suddenly becomes angry and quick-tempered without regard for those around him. Could Nietzsche himself be like that?

AUS: According to everything we know of his contemporaries, Nietzsche acted cautiously in his social environment; seizure of transgression excesses in Kinski style were probably alien to him and remained alien to him when he observed them in others. The self-cultivation prompt from Morgenröthe (1881) he has apparently made himself his own:”The good four. — Redlich Against us and what else is a friend to us; valiantly against the enemy; magnanimous against the defeated; politely — always: that is what the four Cardinal Virtues want us to do. ”5 Nietzsche upheld politeness and refinement not only theoretically but also in practice: Social behavior determined by politeness produces the least amount of friction. In contrast, the fact that he could be berserk on paper (which led to the assumption that he had also been so in life) is another story in the truest sense of the word. But he seems to have had no trouble distinguishing one sphere from another. In fact, politeness included leaving others as they are. In a recording from 1880, he even forged a “new canon for all individuals”: “Be different from everyone else and be happy when everyone is different from the other”6. However, this maxim has remained buried in the estate; Nietzsche never included it in a published work.

PS: Whether he then had occasional outbursts of emotion in the absence of his acquaintances or, when he was unobserved, will probably never be able to reconstruct. But I agree with you absolutely: The image of the Nietzschean as a choleric eccentric doesn't really fit in with what Nietzsche writes about adequate social interaction. But let me now address a perhaps somewhat sensitive topic that also concerns Nietzsche's unobserved private life, but which also concerns many of our readers and has already caused discussion on our blog7: I mean Nietzsche's sexuality. It seems to me that hardly any philosopher speculation about this is so widespread — although this topic is often circumvented in serious research. If I remember correctly, it doesn't play a particular role with Janz, for example. As far as I can see, there are three common competing stories: Firstthat Nietzsche was very inhibited and clumsy when it came to women, although he longed for them — and, according to the myth, he also became unfortunate with syphilis during his only physical intimate encounter with a Cologne prostitute.8 Secondthat, despite his possible infatuation with Lou Andreas-Salomé, he was in reality homosexual and even maintained contacts with young male prostitutes — as Rüdiger Safranski argues in his well-known Nietzsche biography from 2002 and, last but not least, Joachim Köhler in his extensive investigation The Secret of Zarathustra, which was published in 1989 but is largely ignored in research. Thirdlythat he was a sadomasochist with a strong masochistic tendency towards dominant women. The key witness here, curiously enough, is none other than Lou Andreas-Salomé — who is often accused of a certain sadism in dealing with men — herself, who hinted at this variant in her Nietzsche biography of 1894 and published posthumously in the diary of her extended stay in Vienna in 1912/13 with Sigmund Freud even of Nietzsche as “that sadomasochist on yourself”9 spoke. Who, if not she, would have to know, you might think, even though the exact nature of her relationship with Nietzsche is also very controversial. Köhler took up this assumption in the chapter “Knight, Death and Domina” of the book in question and argues, for example, that Nietzsche must have known Leopold of Sacher-Masoch's novels. However, in my opinion, his argument is somewhat stuck, as he identifies suppressed homosexuality and heterosexual masochism in a somewhat kitchen psychological manner.10 — We are certainly touching on speculative territory again, as Nietzsche was unfortunately less open-hearted in this regard than, for example, his arch enemy Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It seems to me that he struggles with the Puritanism of his time and his milieu without therefore pleading for a complete disinhibition of sexuality. There is almost always talk of “smelly normal” heterosexual sexuality, but piquantly enough, there is a noticeable tendency in Nietzsche to think pain and pleasure together — Köhler, for example, interprets the famous “whip sentence” in this sense as a commitment to the whip The woman! —, but also occasionally approving passages about ancient boys' love.11 As a biographer, how do you deal with this? And which side do you take in the dispute over Nietzsche's intimacy?

AUS: The undeniable interest in Nietzsche's sex life reveals a lot about the audience who asks about it and the cultural environment in which this audience lives. For most Westerners and people socialized in the 20th or 21st century, the topic of sex is of eminent importance — which in turn is very worth considering in terms of cultural philosophy: What does it say about a culture and its idea of the formability of one's own way of life when an ideological predominance of sex, i.e. of the tending to be unmanageable, prevails in it? But that is of course not the question you wanted to ask. Looking at Nietzsche, we can therefore simply state soberly: The idea that gender, drive, sexual desires could possibly not have been a capital problem for a philosopher of a previous century is outrageous, even unbearable, for today's audience. This audience must almost compulsively assume that the former person has suppressed something — the essentials — or (possibly even worse) lived it out secretly without cheekily sharing it with posterity.

The biographer therefore feels compelled to comment on this. You're hoping for keyhole stories, new “revelations.” Joachim Köhler made perfect use of this business model as early as 1989 with thin evidence in the realities and texts. I cannot rule out the possibility that Nietzsche Sacher-Masochs published in 1870 Venus in Fur read because he used to consume a lot of literature — so why not Sacher-Masoch, who, by the way, comes across as much more harmless and bourgeois than the “masochism” formed after him would suggest. What I can rule out, however, is that this possible reading has left any verifiable impression in Nietzsche's written legacies. In any case, the parallel position evidence that Joachim Köhler wants to teach about this does not convince me. By the way, Nietzsche actually mentions Sacher-Masoch once, namely in a letter to his publisher Naumann, in a long list of magazine editors who wrote a review copy of Beyond good and evil should get (link). Sacher-Masoch was on this list not because Nietzsche had something particularly piquant about him, but because he saw him as an ordinary journalist among other journalists — if he actually noticed him.

Unfortunately, I can't come up with sparkling erotic revelations in the biography, although these would certainly incite audience interest. Despite certainly better sales figures, I defy the biographer's temptation to inflate trivia about events. In the The genealogy of morality Nietzsche thinks about what philosophers should think about ascetic ideals. The argument is aimed at making use of asceticism: philosophers appear to be radical advocates of their own interest in remaining undisturbed. They want to keep themselves free of irritation, both in terms of external distraction and in terms of their own sensuality: “Peace in all basements; all dogs nicely put on a chain; no barking of enmity and shaggy rancune”12.

He never revealed exactly what dogs Nietzsche thought were in his basement. And today's speculation about dog species reveals something in particular about the disposition of the respective biographical speculators. There is something involuntarily funny about wanting to have the “dispute over Nietzsche's intimacy” today. Anyone who adheres to biographical honesty will follow the methodological guidelines set by Nietzsche in antichrist ”Ephexis in interpretation”13 says: You should abstain from a judgment where reliable material is missing in order to be able to form a verdict.

PS: Yes, what I actually find sad about this whole discussion is that they absolutely try to squeeze Nietzsche into some kind of drawer of today's defined sexual identities. Michel Foucault should tell us with his study at the latest Sexuality and Truth (1976) have proved otherwise: This entire modern category apparatus (homosexuality, masochism, sadism...) and the idea of sexuality as an “actual”, “authentic” identity are historically very recent and Nietzsche will certainly not have located himself within this framework at all, but simply followed his needs — and probably saw himself primarily as a philosopher, philologist, free spirit, not primarily as a sexual being, even though he repeatedly expresses the instinctive character of Thinking emphasizes14. We must indeed be very careful not to be blinded by the reign of “King Sex” (Foucault), which is also very repressive and impoverishing as far as our possibilities of being are concerned. In any case, the end of the 19th century, which was supposedly so bourgeois, was open enough to recognize an author like Sacher-Masoch as a reputable writer. He was a bestselling author, not an eccentric nerd. — Perhaps it is precisely in our obsession with the sexual that we are stuck in this regard? But today there is also serious discussion on the Internet about whether Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar were homosexual...

What can hardly be denied, however, is, as it seems to me, that Nietzsche, when you only start from his lyrics and ignore everything else, repeatedly refers to the topic of sexuality.15 Even for his teacher Schopenhauer, the “will to live” was not least an omnipresent will to procreate. Freud later based his psychoanalysis on this idea and was also inspired by Nietzsche. The already mentioned Lou Andreas-Salomé, for example, was later also a student of Freud and wrote several important contributions to psychoanalytic theory and the theory of eroticism. He was later perceived by many as a prophet of a Dionysian liberation of sex, especially in its' perverse 'dimension, I am thinking of Georges Bataille, Antonin Artaud, the first Freudo Marxist Otto Gross or even sex-positive feminism (starting at the turn of the century with Hedwig Dohm, Lily Braun or Helene Stöcker, for example). There is also evidence of a certain Nietzscheanism in the notorious Wilhelm Reich and later in Herbert Marcuse. Numerous other names could be mentioned here, but what I'm actually getting at is: Do you think this strand of Nietzsche reception is purely a projection effort or is it not based on Nietzsche's criticism of the puritanical hypocrisy of his perhaps not so humble time and his concept of Dionysian?

AUS: That is the remarkable thing about Nietzsche: He invites to a wide variety of and often adversarial receptions, all of which refer to him with a certain right. On the one hand, he appears as the great thinker of physicality, who ridicules any shift of heavyweight into an ethereal, pure spiritual world. The Dionysian intoxication seems to find a lawyer in him. On the other hand, it stands for “pathos of distance”16, the great disillusionment, the great cold that evades all physical constraints. If for some he is the philosopher of orgiasm, for others he is the philosopher of the strictest philosophical asceticism — not asceticism for himself, but for the sake of merciless knowledge. But can you, if he continues, really want the insight? Why a will to truth and not much rather a will to falsehood?

If we call on Nietzsche as a witness for this or that, he will evade very quickly. He is a highly unreliable witness in every way. Perhaps it would be wiser to renounce his testimony, his patronage for this or that. And not to hope for his help — neither during the sexual revolution nor in all sorts of counterrevolutions. At best, Nietzsche is helping himself.

III. Could Nietzsche Help Himself?

PS: I have nothing to add to that. There is just one last quick question that comes to mind for me. What would you sum up after all your years and decades of intensive engagement with Nietzsche's life and work: Was it a person who yourself was able to help?

AUS: A remarkable question! In fact, he was a person who always knew how to help the people who could help him. He had an amazing ability to use other people for his purposes and at the same time pathetically maintain the fiction that he was there all alone, abandoned by all over the world. That would be an indication that he could very well help himself — through others — in matters related to life. And even beyond instrumentalizing others, I tend to attest to him great talent for self-help. Philosophically anyway: Dead ends into which he maneuvered — starting with Schopenhauer and Wagner to Lou Andreas-Salomé and Paul Ree to all sorts of disease overloads and late self-deification — proved to be reciprocal experiences that he was able to make use of, usually not according to the rules of consistent closing, whether through daring horse jumps, whether through daring horse jumps through Kess-ironic Volten. If helping himself means cooking up a coincidence, then he has succeeded surprisingly often. It shows the power of philosophizing.

PS: Thank you very much for this informative conversation.

AUS: It was a pleasure. Let us keep trying with the power of philosophizing.

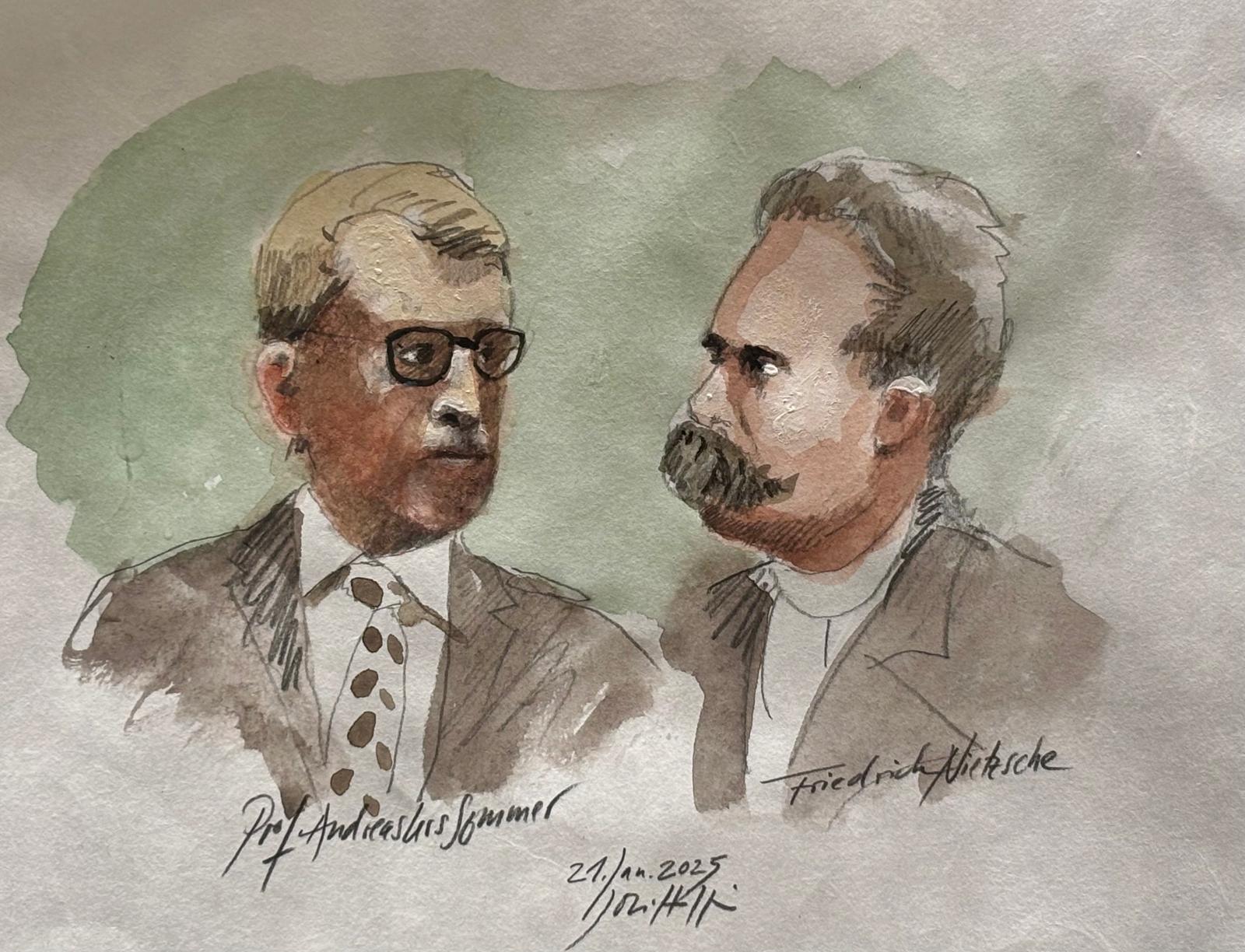

Andreas Urs Sommer, born on July 14, 1972 in the Swiss canton of Aargau, has been a professor at Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg since 2016 and managing director of the Nietzsche Research Center based there since 2019. He completed his Habilitation in 2004 under the supervision of Werner Stegmaier with a study on the philosophy of history with Kant and Bayle at the University of Greifswald. Since 2014, he has been head of the Nietzsche Commentary Research Center at the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and has contributed several volumes to it himself. Among other things, he published the monographs Encyclopedia of imaginary philosophical works (Frankfurt am Main 2012), values. Why you need them even though they don't exist (Stuttgart 2016), A democracy for the 21st century. Why the people's representation is outdated and the future belongs to direct democracy (Freiburg, Basel & Vienna 2022) and the excellent introductory volume Nietzsche and the consequences (Stuttgart 2017).

Sources

Andreas-Salome, Lou: Friedrich Nietzsche in his works. Vienna 1894.

This. : At school with Freud. Diary of a year 1912/13. Taching am See 2017.

Blunck, Richard: Frederick Nietzsche. Childhood and youth. Basel & Munich1953.

Foucault, Michel: The will to know. Sexuality and Truth I Frankfurt am Main 1977.

Janz, Curt Paul: Frederick Nietzsche. biography. Munich 1978/79. 3 vols.

Koehler, Joachim: Zarathustra's secret. Friedrich Nietzsche and his encrypted message. Reinbek near Hamburg 1992.

Niemeyer, Christian: Nietzsche's syphilis — and that of others. A search for clues. Baden-Baden 2020.

Safranski, Rüdiger: Nietzsche. Biography of his thinking. Munich & Vienna 2000.

Yalom, Irvin D.: And Nietzsche cried. Transacted by Uda Strätling. Munich 2001.

Source of the Article Image

Johannes Hüppi: Andreas Urs Sommer & Friedrich Nietzsche (2025).

Footnotes

1: See Jonas Pohler's report on the annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society dedicated to this commentary in 2024 on this blog (link).

2: Morgenröthe, Preface, paragraph 5.

3: See in particular the section dedicated to this work in Ecce homo (link).

4: Cf. Paul Stephan's articles Mythomaniacs in a short time. About Klaus Kinski and Werner Herzog on this blog (link).

5: Aph 556.

6: No. 3 [98].

7: See in particular Henry Holland's article With Nietzsche and Marx in the round of inheritance (link) and Christian Sährendt's contribution Dionysus without Eros. Was Nietzsche an Incel? (link).

8: This story was recently updated by Christian Niemeyer in his extensive study Nietzsche's syphilis — and that of others.

9: At school with Freud, P. 134.

10: A “diagnosis” which, however, also formulated Andreas-Salomé with reference to Nietzsche, who also spoke to the philosopher about this topic (cf. ibid.).

11: However, these can be counted on the fingers. The most important are Human, all-too-human Vol. I, Aph 259, Morgenröthe, Aph 503 and Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, Aph 47.

12: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 8.

13: Paragraph 52.

14: See e.g. Subsequent fragments 1883, No. 7 [62].

15: For example, he criticizes Christianity primarily for its rejection of sexuality (see, for example, AC 56 &law) and even the lack of sex education among “distinguished women” (FW 71) and denounces the hypocrisy of monogamous marriage (cf. MA I, 424). The “intoxication of sexual stimulation” is the “oldest and most original form of intoxication” (GD, rambles, 8), although he also spoke of an original “lust for cruelty” (GM II, 7) and also repeatedly associates it with sexuality (see already GT 2).

16: See, for example On the genealogy of morality, paragraph I, 2.