Nietzsche’s Monkey, Nietzsche’s Varlet

The Oswald Spengler Case

Nietzsche’s Monkey, Nietzsche’s Varlet

The Oswald Spengler Case

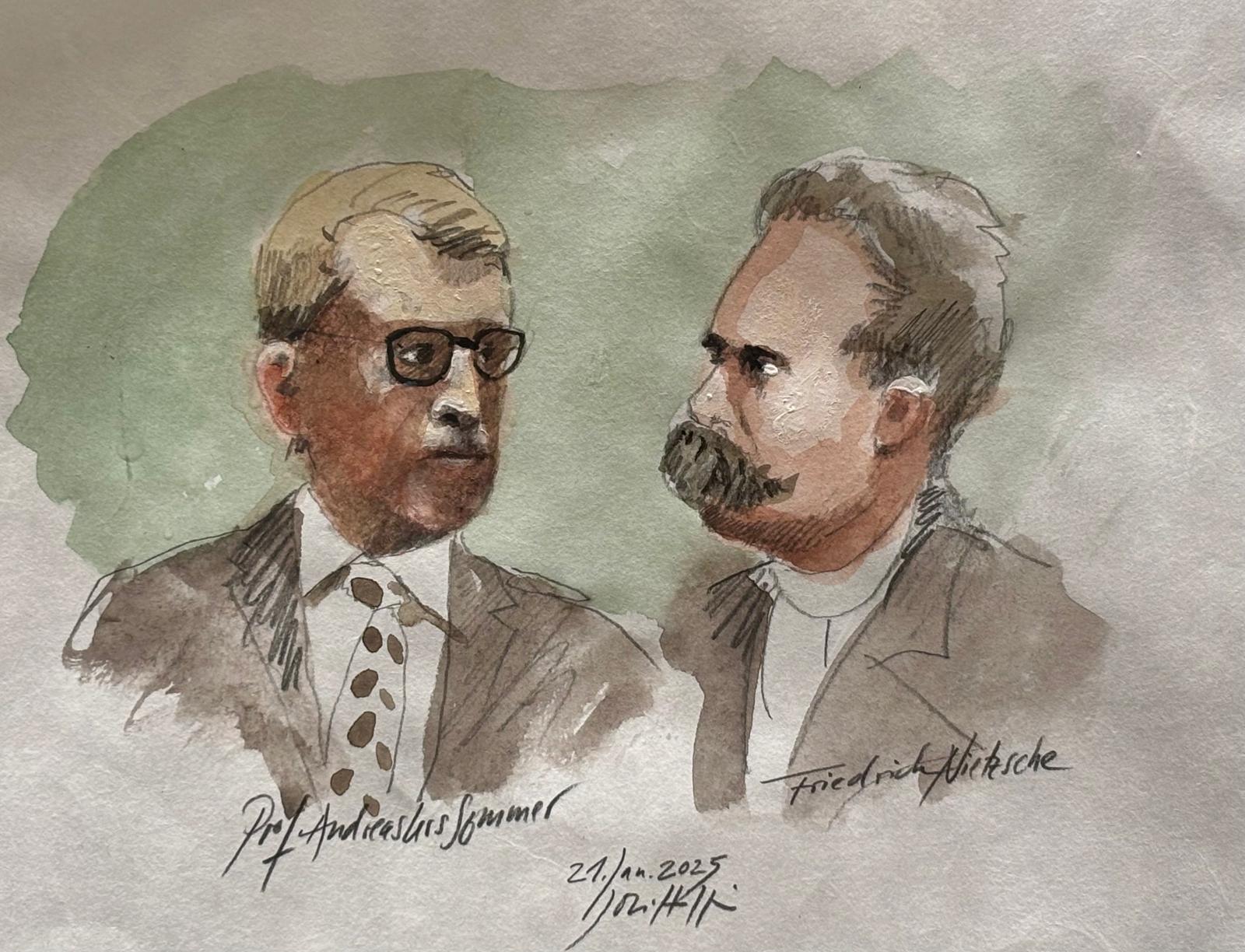

In the following article, Christian Saehrendt gives a brief insight into the work of one of the most controversial but also most influential Nietzsche interpreters of the 20th century: the German philosopher Oswald Spengler (1880—1936). The author of The fall of the West (1917/22) is considered one of the most important representatives of the “Conservative Revolution,” an intellectual movement that was significantly involved in the cultural destabilization of the Weimar Republic before 1933. Largely forgotten in Germany, it continues to be eagerly received in a global context, such as in Russia.

Oswald Spengler is almost forgotten in German-speaking countries today. A hundred years ago, the Munich philosopher was an attractive figure in public life and at the same time one of the most prominent Nietzscheans.1 His monumental work The fall of the West. Outlines of a morphology of world history had made him famous. Spengler was one of the first and most successful anti-Western doom marketers who were read with lustful shivering by a large audience — especially in the West. It is less well known that Spengler also assumed at the time that there was an irreconcilable conflict between Russia and the West, from Russia's “truly apocalyptic hatred” of the West. This is still (or again) well received today by extremist Russian ideologues such as Alexandr Dugin. As a result, Spengler has become relevant again — even for us in the eternally declining West.

For almost ten years, Spengler had Fall of the West worked. The first volume was published in 1917, the second in 1922. From 1923, C.H. Beck then brought both volumes onto the market together, including a magnificent leather-bound edition. The book had an enormous impact at the time and was understood as a culturally pessimistic wake-up call, especially in the German Reich, which had just lost the First World War, and was explicitly referred to the fate of the nation.

But the intellectual all-rounder Spengler aimed in his Morphology of world history not only on the German Reich, but also tried his hand at global historiography. In contrast to the linear progress narrative of modernity, which was still common at the time, he espoused a thesis according to which advanced civilizations periodically rise, flourish and fall. His cyclical understanding of history outlines a sequence of cultures, each lasting around 1,000 years. Now, at the beginning of the 20th century, it seems to him that the culture of the Christian West is at an end — caused by capitalism, greed for money, excessive individualism, and lack of spirituality. But at the same time, he sees the beginning of a new era, the rise of a new high culture, on the eastern edge of Europe. Often hidden in footnotes, Spengler repeatedly talks about Russia, which stands in stark contrast to the doomed West. He attests to Russian culture the potential to overcome capitalism and technicism that were decisive for the fall of the West, “the Russian,” whose “completely mystical inner life sees thinking in money as a sin.”2, will “build a completely different world around itself, in which there is no longer any of this diabolical technology. ”3“Nowhere was the reaction to Spengler's main work as rapid, massive and broad as in post-revolutionary Russia,” writes political scientist Zaur Gasimov.4 In the ideological conflicts of the early Soviet period, Spengler was received in the context of a conservative and religious search for Russian identity. Spengler's work was banned as “religious literature” by the Soviet authorities soon after; he was denied appearances in the Soviet Union. It was only during perestroika and especially in the early 1990s that he was rediscovered, resulting in new translations and reprints of his Doom with editions of tens of thousands of copies. Even at the beginning of the new millennium, the Russian plumbing boom continued; numerous scientific publications were published about it.5 In his book Eurasian Mission (Evraziyskaya Missiya, 2005) Alexandr Dugin addressed Spengler several times, whom he regards as a thought leader and as a reference for his current “Eurasian Movement.” Dugin wrote, among other things, that Spengler's programmatic pairs of terms “culture and civilization,” “organic and artificial,” “historical and technical” could still be used today.6 Even before the invasion of Ukraine began, Dugin had rejoiced: “The West is on the brink of collapse”7, while Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov gave a speech in the summer of 2022 that Spengler's analysis of the “fall of the West” was “very far-sighted.”8 For years, Foreign Minister Lavrov has accompanied his country's increasingly aggressive foreign policy with speeches about “Russia's responsibility in world politics,” referring to Spengler, around 20089 or 201110. Russian TV star presenter Vladimir R. Solovyov, on the other hand, suggested to his viewers at the beginning of 2023: “Life is extremely overrated.” Life is only worth living if you are prepared to die for something.11 Here, too, Spengler's image of man is in the room. The fact that people in the West are constantly working on “perfecting the ego” is something, the German private scholar fables, “which the real Russian regards as vain and despises. The Russian, willless soul, whose original symbol is the infinite plane, tries to give up in the brotherly world, the horizontal, serving, nameless, losing itself. ”12 A hundred years ago, Spengler was hotly debated in Germany, and then he was put on file as a cultural pessimist and unscientific oath. Different in present-day Russia: From Lavrov, Dugin and Solovyov's throats, you can clearly hear the voice of the German doom prophet.

In the Weimar Republic, Spengler increasingly appears as an intellectual heir and finisher of Nietzsche's world of thought — or is interpreted as such in a flattering way. In 44 places alone in his downfall-Bestsellers refers to Spengler Expressis verbis in Nietzsche or quote him. With the support of jury member Thomas Mann, Spengler received the Nietzsche Archive Prize in 1919, which was donated by entrepreneur Christian Lassen. In February 1923 he gave his first lecture in the archive with the title “Money and Blood,” in June 1923 he was elected to the board of the Nietzsche Archive, and in 1924 alone he traveled to Weimar seven times to give further lectures and attend meetings.13 It is remarkable that he used music as the most important link between Nietzsche and his Morphology of world history referred to. In a presentation given by Spengler on October 15, 1924 in the Nietzsche Archive on the subject of “Nietzsche and his Century,” he pays tribute to his Birth of Tragedy as a decisive source of inspiration for the global historiographical approach of Doom:

The liberation came from the spirit of music. The musician Nietzsche created the art of blending into the style and rhythm of foreign cultures, beyond and often in contradiction with the sources...14

At the end of the preface of Doom Spengler seems to bow down to his great idols, to “Goethe and Nietzsche. I have the method from Goethe, the questions from Nietzsche...”15 In fact, in his book and in his lectures, Spengler stylizes himself as the person who continues to think and answer Nietzsche's questions. Almost as a schoolmaster, he evaluates and corrects Nietzsche and becomes a true expert and finisher of his world of thought, as the following example from the downfall shows.

Spengler praises: “It will always be Nietzsche's great merit to have been the first to recognize the dual nature of all morality” (p. 981), but at the same time reprimands: “Nietzsche has remained far removed from a truly objective morphology of morality” (p. 403), and sweeps him off in general:

But he himself did not fulfill his demand for the thinker to set himself apart from good and evil. He wanted to be both a skeptic and a prophet, a moral critic and a moral proclaimer. That is not compatible. You're not a first-rate psychologist as long as you're still a romantic. And so here, as in all his decisive insights, he reached the gate, but stopped before it. (P. 441)

The following example also shows the typical mix of rebuke, praise and pure speculation with which Spengler treats Nietzsche. He criticizes: “If Nietzsche had observed his time more prejudiced [...], he would have noticed that a supposedly specifically Christian morality of compassion in his sense does not exist at all on the soil of Western Europe” (p. 443), then praises Nietzsche that he is “the Faustian nihilist” who shatters yesterday's ideals (p. 456), and then claims: “The Third Reich is the Germanic ideal, an eternal tomorrow, to which all great people like Nietzsche [...] attach their lives.” (p. 465)

With regard to music and art, Spengler's thesis of cultural standstill in the modern age is of interest. When reading the Doom It is noticeable that he locates the actual power of the civilizational age in his technical artifacts and in the sciences, “his cultural achievements, i.e. the still epigonally carried away reminiscences of the long-disappeared phase of cultural youth or maturity, are subordinate to this, they are alive and boring. ”16 This impression cannot be denied, especially when it comes to the contemporary schedules of theaters, opera houses and renowned museum collections. Well-known literary models, pieces and works from the 19th century and the turn of the century still dominate today's high culture. In this sense, Spengler also addresses the controversy between Wagner and Nietzsche:

Everything Nietzsche said about Wagner also applies to Manet. Seemingly a return to the elementary, to nature [...] [,] her art means yielding to the barbarism of cities, the incipient dissolution, as it expresses itself in the sensual in a mixture of brutality and refinement [...] [.] Artificial art is not capable of organic development. It marks the end. It follows that Western visual art is irrevocably at an end. The crisis of the 19th century was death throes [...] [,] what is now practised as art is powerlessness and lies, music after Wagner as good as painting... (p. 377)

Spengler therefore sees Wagner's art as an eclectic and commercial product of modernity, as an enthusiastic and untrue spectacle — without any mystical depth.

Summa summarum Spengler sought to push Nietzsche into the role of a forerunner of his own philosophy. Nevertheless, experts today regard Spengler as a mere epigone of Nietzsche in many ways:

This could be illustrated on the basis of an extensive list, which included all common views. It would include not only initial patterns of interpretation of the fall of the West, such as the analysis of decadence, the historicized will to power, the meaning of ancient culture or the ambivalent concept of race, but also numerous descriptive details. In addition, there is the unmistakable stylistic reference to the admired role model. Nietzsche — unlike Goethe — is present on almost every page of Spengler.17

Spengler achieved considerable prominence in the Weimar Republic, but also found numerous envious and opponents who rejected him, sometimes for good reasons, in terms of content or politics. Among other things, they voiced the allegation that he was diluting Nietzsche's ideas and presenting them in an overly populist and contemporary way. Thomas Mann, who was still in 1919 — like his side notes in the first volume of Doom show — was considered Spenglerian, was increasingly critical and derogatory about Spengler in the following years, for example in the famous speech given on October 13, 1922 From the German Republic On the occasion of Gerhart Hauptmann's 60th birthday18 or in the essay About Spengler's teaching19. Among other things, Mann Spengler called “Nietzsche's clever monkey” and refers to a character from the Zarathustra, a companion who is just as loyal to the Master as he is extremely annoying, who as the “monkey [] Zarathustra's”20 is referred to as.21 The prominent liberal cultural politician and convinced Nietzschean Harry Graf Kessler made no effort to hide his unwillingness behind literary allusions. He reported in brutal openness about the 1927 Nietzsche Conference in Weimar, at which Spengler spoke in the overcrowded hall about “Nietzsche and the 20th Century.” The presentation was a single “debacle”:

A fat priest with a fat chin and a brutal mouth — I saw Spengler for the first time — carried out the most hackneyed, trivial stuff for an hour [...] [,] not a thought of his own [...]. An unfortunate embarrassment for the Nietzsche Archive to have this half-educated charlatan speak. The presentation was so shallow [...] [,] maybe he is the first Nietzsche priest.22

Sources

Gasimov, Zaur: Spengler in present-day Russia. On the New Eurasian Reception of Cultural Morphology. In: Gilbert Merlio and others (eds.): Endless plumbing. A reception phenomenon in an international context. Frankfurt am Main 2014, pp. 243—257.

Dugin, Alexander: Eurasian mission. An Introduction to Neo-Eurasianism. London 2022.

Felken, Detlef: Oswald Spengler. Conservative thinker between empire and dictatorship. Munich 1988.

Thomas Mann: About Spengler's teaching. In: Collected works, volume 10: Speeches and essays. part 2. Frankfurt am Main 1974, pp. 172—179.

Ders. : From the German Republic. In: Collected works, volume 11: Speeches and essays. Part 3. Frankfurt am Main 1974, pp. 811—852.

Pfeiffer-Belli, Wolfgang (ed.): Harry Graf Kessler diaries 1918 to 1937. Frankfurt a. M. 1996.

Sieferle, Rolf Peter: The Conservative Revolution. Five biographical sketches. Frankfurt am Main 1995.

Spengler, Oswald: The fall of the West. Outlines of a morphology of world history, Munich 1923. Used here: paperback edition dtv (Munich 2000).

Wenner, Milan: Exciting proximity. Oswald Spengler and the Nietzsche Archive in the Context of the Conservative Revolution. In: Ulrike Lorenz & Thorsten Valk (eds.): Cult — art — capital. The Nietzsche Archive and Modernity. Göttingen 2020, pp. 133—152.

Zumbini, Massimo Ferrari: sunsets and dawns. Nietzsche — Spengler — Anti-Semitism. Würzburg 1999.

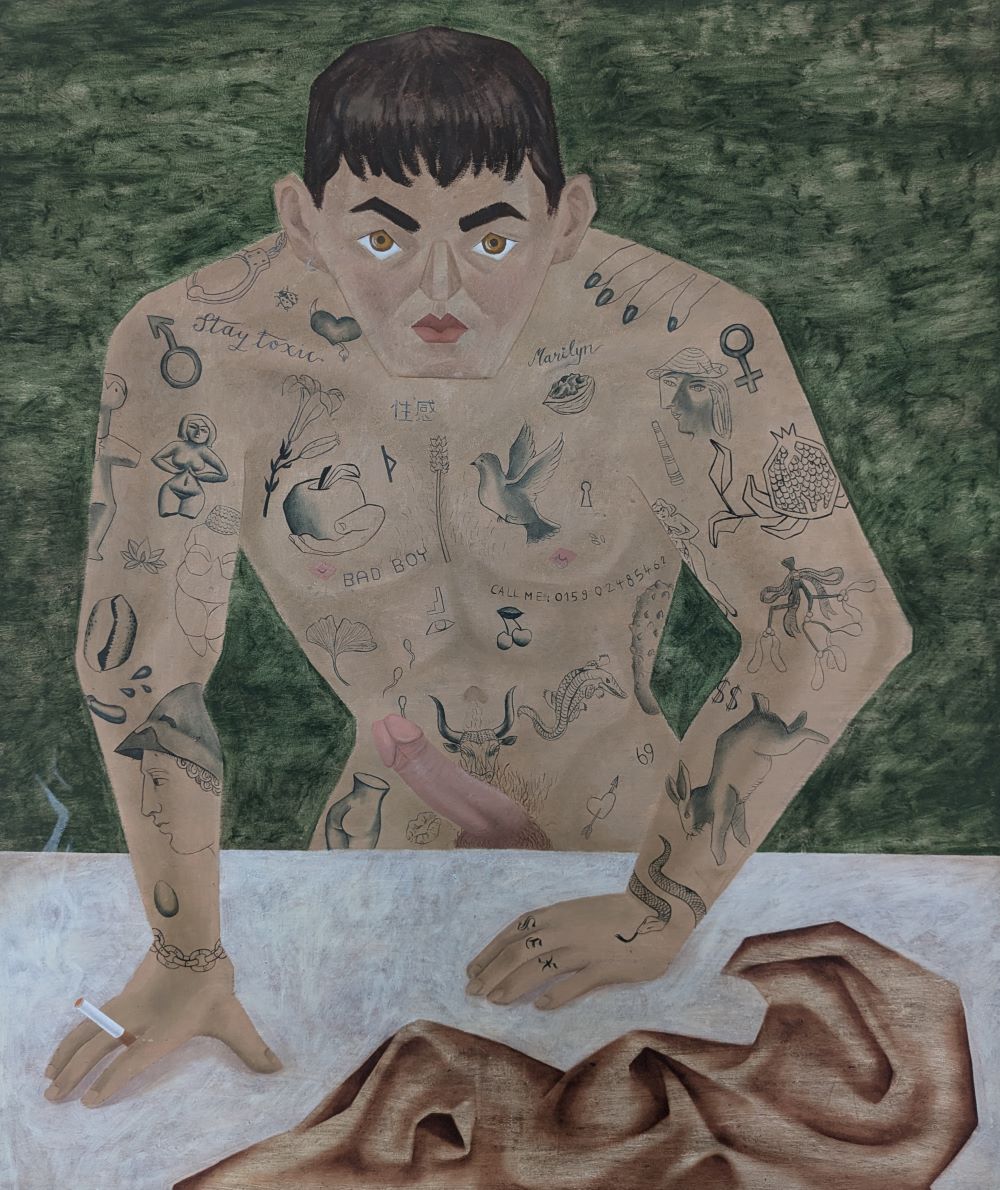

Source of the article image

Spengler in the Russian birch forest. Christian Saehrendt, oil on canvas, 2005.

footnotes

1: See the review article Milan Wenner, Exciting proximity.

2: Spengler, The fall of the West, P. 1181.

3: Ibid., p. 1190.

4: Zaur Gasimov, Spengler in today's Russia, P. 243.

5: See ibid., p. 245 et seq.

6: Cf. Alexander Dugin, Eurasian mission, P. 7.

7: Quoted from Dugin's German-language website “The 4th Political Theory” (retrieved on 7/5/2024).

8: This is how the pro-Kremlin news agency Ria Novosti reproduced it (cf. Editorial Network Germany, 10.7.2022).

9: Cf. Speech by Russian Foreign Minister S. V. Lavrov at the opening of the international conference of the Bergedorf Round Table “Russia's Responsibility in World Affairs,” Moscow, October 25, 2008. https://mid.ru/de/foreign_policy/news/1624365/ (retrieved on 7/5/2024).

10: Cf. Speech at MGIMO University of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Moscow, September 1, 2011. https://mid.ru/de/foreign_policy/news/1602124/ (retrieved 7/5/2024).

11: Russian Media Monitor, 21/4/2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQsZu44xAUY (min. 2:14).

12: Spengler, The downfall, P. 394.

13: Cf. Detlef Felken, Oswald Spengler, P. 158.

14: Quoted by Massimo Ferrari Zumbini, Sunsets and Dawns, P. 45.

15: Spengler, The downfall, preface, S. IX.

16: Rolf Peter Sieferle, The Conservative Revolution, P. 111.

17: Felken, Oswald Spengler, P. 164.

18: Cf. P. 841.

19: Cf. P. 173.

20: So Zarathustra spoke, From passing by.

21: Cf. Zumbini, Sunsets and Dawns, P. 38.

22: Wolfgang Pfeiffer-Belli, Harry Graf Kessler diaries 1918 to 1937, p. 574 f. (15/10/1927).