Homesick for the Stars

Prolegomena of a Critique of Extraterrestrial Reason

Homesick for the Stars

Prolegomena of a Critique of Extraterrestrial Reason

On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin achieved the unbelievable: He was the first person in history to leave the protective atmosphere of our home planet and circumnavigate the Earth in the Vostok 1 spaceship. In 2011, the anniversary of this “superhuman” act was declared International Manned Space Day. The stars aren't that far away anymore. With the technical progress achieved, the fantasy of expanding human civilization into space takes on concrete plausibility. The following text attempts to philosophically rhyme with these prospects and finally describes the approach of a possible space program from Nietzsche. Although airplanes didn't even exist during his lifetime, his concepts can still be applied to this topic in a productive way, as is so often the case.

Editorial note: We have explained some difficult technical terms in the footnotes.

“He has an eagle's eye for the distance,

He doesn't see you! — he only sees stars, stars! ”

Nietzsche, Without envy

I. Earth Now

One of Nietzsche's best-known appeals is to “remain loyal to the earth.”1 With this, Nietzsche squeezes like a modern, philosophically minded Thracian maid2, from the fact that contrary to the metaphysical dynamics that infect humans with the insanity of a supernatural, supposedly truer reality, it is important to make friends with the human being with this world. The particular difficulty would be that, after all the centuries of cultural training with beliefs and feelings of faith, if this training continued, it would lead to withdrawal: “When will all of these give us shadows Gottes Don't darken anymore? When will we have completely deified nature! When will we be able to start naturalising ourselves humans with pure, newly found, newly redeemed nature! ”3 Nietzsche therefore promotes a kind of philosophical countermadness against the insanity of the religious “backworlds” and as support and encouragement for persevering from God. The true revelation is the revelation of the emptiness and hostility of revelation that defamed the riches of life. As long as God is alive, the earth must be dead. Only when God is dead can the earth begin to live. Apocalypse Now than Earth Now.

II. Earth escape

For some time now, there has been a post-metaphysical form of infidelity to Earth. Three motifs can be differentiated. One could argue — the more-knowledge hypothesis — that the push into space is a simple continuation of the human drive to research. If Aristotle claims that all people strive for knowledge, striving into the cosmos would not be a qualitatively different form of terrestrial attempts to create knowledge.

The fact that it is not the scientific but the social interpretation of space travel that is plausible is confirmed by reference to the plans of a “multiplanetary” civilization, such as those impressively successfully promoted by creative entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk with his company “Space X”.4 More profound motifs can also be found in the undeniable philanthropic intentions of this form of space colonization, which wants to establish its first outpost on Mars. According to this, it is primarily a reason to flee from a Third World War, possibly driven by climate change or even by the effects of artificial intelligence, which urges the establishment of a refuge for human civilization on Mars — and not on the Moon that is close to Earth and therefore uncertain. This form of escape from the earth — the flees forward hypothesis — has less altruistic connotations, as the idea of an extraterrestrial Noah's Ark gives the unnoble impression of possibly being an exodus for a rich elite. In addition, the shadow of the question of who decides on the form of social interaction beyond nation states and legal systems inevitably casts a twilight on the utopia of a “multiplanetary humanity.”

A third interpretation of the departure from the earth — the we—wouldn' t be alone hypothesis — is based more on a psychological motive. She assumes that the main driver for expansion into the void of space is an emptiness of the psyche. Curiosity and longing for other intelligent lives in particular inspire this desire for space. The Fermi Paradox from 1950 — life has had so many millions of years and yet we receive no signals from other advanced civilizations — or even the Drake formula from 1961 — which gives the variables that determine the probability that communication between another capable and willing intelligent civilization in our galaxy is possible — are the most prominent examples of theorizing loneliness that longs for another life. A first concrete contact attempt was the Arecibo message, which Frank Drake and Carl Sagan sent into space from Puerto Rico on November 16, 1974. However, real cosmological colleagues vehemently pointed out that such efforts could also be quite risky and criticized the Arecibo message's naive willingness to talk: It could not be assumed that aliens were peaceful. The vastness of space is a protection against unpleasant contacts. It works, as brilliantly illustrated in the rightly very successful Trisolaris-Trilogy (from 2007) by Liu Cixin, like a “dark forest.” Whether it's tragedy or luck: The 100 billion galaxies in space, each with 100 billion stars, make it appear very likely that there is intelligent life somewhere else. At the same time, however, the expansion of the universe makes it appear very unlikely that communication is possible. Even though we're not alone, we're alone.

The fact that curiosity to enter the dark forest prevails was ultimately shown by the Breakthrough Starshot project, launched in 2016 and ironically supported by Stephen Hawking, one of the greatest physicists of recent decades, who was one of the greatest physicists of recent decades, who was one of the critics of the Arecibo message. The aim of this “star venture” (Sagan) is to accelerate a type of camera so much that it can reach the exoplanet in a relatively short period of time in order to transmit data from there. Maybe then we won't be so alone anymore.

III. The dialectic of space travel

On April 12, 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin circumnavigated the Earth aboard the Vostok 1 spaceship in around 100 minutes. Two years later, Adorno wrote in a text about Gustav Mahler Song of the Earth:

It is said [...] of [Earth] that it has stood firm for a long time — not forever — and the person taking leave even calls it dear Earth as that included in disappearance. It is not space for the work, but what fifty years later the experience of flying at great heights was able to catch up with, a star. From the gaze of music that leaves it, it rounds off into a manageable sphere, as it has already been photographed from space, not the center of creation but a tiny and ephemeral5 [...]6

Of course, Adorno must be Spin Doctor An anonymous gnosis7 With perfect siren sounds, give his speculation a turn of the negative and discouraging at the end. He sums up: “But the Earth, which has moved away from itself, is without the hope that the stars once promised. It sinks into empty galaxies. Beauty lies on it as a reflection of past hope, which fills the dying eye until it freezes to death under the flakes of demarcated space. ”8

Against Adorno, however, a philosophically more hopeful message can also be derived from his inspiring thoughts. Due to concerns about space travel and not just through emotional flight through Mahler's music, an “Earth moving away from itself” appears as an ephemeral entity. This is how the philosopher's speculative eye rediscovers the earth. Through the telescope of thoughts, it appears as a vulnerable rarity. The whole thing is truly vulnerable. The Earth is the cosmic Safe Space. If the late Heidegger speaks of Earth as the “crazy star,” Adorno could describe the Earth as the “ephemeral star.”

The dialectic of space projects consists in the fact that their impact of the positivistic general reveals the basal fragility of the Earth's habitat as a valuable feature. The expansive movement into infinity triggers a reflection that can now set the understanding of home to planetary standards. The completely abandoned earth shines in the sign of ephemeral homeliness. The contemplative astronaut can think of the global as the local “among the flakes of demarcated space.” Experienced by the tremendous breathless cold of space, the Earth becomes a “global village” (McLuhan). This gives the Transterrist a non-down-to-earth attitude. It could be embodied as a cosmopolitan priority for the autochthonous. The other becomes a local who is allowed to keep his stranger.

Only the curriculum of temporary cosmopolitanism enables a non-narrow-minded and non-formalistic cosmopolitanism. This earth suitability test or terrestrial Matura could be referred to as a “Gagarium.” He required a flight lesson for more robust minds; for empathic spirits, Mahler's music or an intensified philosophical reflection could also be sufficient. Such provoked whining and shuddering triggers a catharsis: The terrifying stranger of the starry sky around you gives a sense of world change ideas and their strict customs, which are lived too categorically to be suitable for general decoration on the “dear earth.” The stress test of being in space is passed every day as a result of the fact that all systems on board the “Spaceship Earth” (Buckminster Fuller) not only work, but that there is civil cooperation, which enables a liveliness that can surpass itself again and again. Only those who have been far away have “the freedom to be free” (Arendt). Only when the “house piety” (Goethe), which only wants to promote one's neighbour, attains the breadth of “world piety”, does one become a capable cosmonaut in coexisting and co-competing worlds of participation. In fact, one might think, in view of the authoritarian socialism of his home country, Gagarin would have had to emigrate to the liberal West immediately after landing.

IV. The “ascetic star”

For Nietzsche, an infidelity to Earth leading to a new faithfulness — the experience of space as an affair that reinforces open marriage with the Earth — would presumably be a seductive idea. On the other hand, he would still see the metaphysical forces at work as a thirst for knowledge, as a social flight movement, as an expression of loneliness. The dynamism of emigrating to a real life beyond leaves the wealth of this world undetected. The expansive drive into space testifies to an ascetic view of the earthly, all-zuearthly earth.

Compared to the activity of overcoming Earth existence through space travel, Nietzsche's eruption project to the stars could be understood as a spiritual expedition. It thus complements the Gagarium. It is important to him to get rid of the metaphysical slag of a millennia-old tradition from thoughts and communities. Nietzsche's speculative view of the Earth explains it as an “ascetic star,” as a planetary penal colony of resentful believers who make life difficult for themselves for metaphysical reasons:

Read from a distant star, the Majuscle script would perhaps seduce our earthly existence into the conclusion that the earth was actually the ascetic Stern, a corner of displeased, haughty and adverse creatures who couldn't get rid of a deep annoyance of themselves, of the earth, of all life and would hurt themselves as much as possible for the pleasure of woe: — probably their only pleasure.9

Nietzsche's philosophy rebels against this grumpy way of life. She does this using the method of honest reflection. However, this anti-ascetic is once again gaining its own ascetic. In her merciless analyses, the transfiguration branch on which you sit yourself is also sawn. It disillusiones and depresses when you the mass of “spirit of gravity.”10 Become who you are: There is always a hope for Advent11, a hope for the ultimate justice of the Last Judgment, a self-sacrificing empathy for distant injustices, a distrust of works and the freedom of the human as original sin, a categorical condemnation of transgressions of certain commandments as absolute goodness, a tragic grief for the remoteness of true being.

V. Sternwerdung

Nietzsche also reflects on the limiting effects of liberating reflection. Because relentless self-analysis as a permanent state becomes an anti-ascetic ascetic that easily loses sight and sense of an beyond the ascetic star, a good “will to appear” is needed12. It is precisely this appearance for Nietzsche, as for Adorno, in art. However, art is gaining expanded significance for Post-Wagnerian Nietzsche. Art becomes an art of living. And for the free spirit, the art of living consists in moving oneself into an “artistic [] distance.”13 To empathize with yourself. Philosophy is the art of turning point. The capable thinker sees breaking up with himself as thinking. One means of this is also for Nietzsche to become more clear about his cosmic dimension. Like Adorno, Nietzsche comes to the conclusion that the mere existence of life in the form of humans is in itself an unbelievable cosmological coincidence. The astral order in which we Being able to live and think about life is an exception when you look at the vast expanse of space around us.14

However, this aphorism is also one of the passages that reveals a fatal ambiguity in Nietzsche's thinking. On the one hand, in his middle and late thinking, he follows the line that the fragility of life must be protected. Being is too hard to endure without pretense. The art of living is necessary to live brightly.

On the other hand, like something from this cosmological reflection, there is also a view of nature as brutal chaos, which allows one's own brutality to be understood as a quasi-natural action. If the law of the universe is cold chaos, then a reckless will to power can be understood as law-abiding action. The late Nietzsche in particular increasingly falsely substantiates the transfiguration of the truthful animal into an ontology of chaos, which then legitimizes a lethal naturalism of power.

However, reducing Nietzsche only to this reading once again demonstrates a philosophical will to power his interpretation. This misrepresents the view of Nietzsche's promising space program. This is about an existential revaluation of the values of the ascetic star. In his thinking, Nietzsche harbours the hope of an exodus from the world within the world. It is about educating yourself in such a way that you develop an intelligent zest for life beyond the annoyance of life and resentful desire for retaliation for this state of affairs. Simply protecting the ephemeral on the ephemeral earth is not enough. It is too little, just a careful wokelinks Safe Space To be for others and it is not enough just to conservatively meet the professional obligations of daily demands. Both would be too boring, would In the Long Run Cause displeasure, which again predisposed to the ascetic intensities of a morality of condemnation. The ephemeral is to be increased to a mentally stimulating vitality:

Heal yourself, good cart pushers,

Always “the longer the better,”

Always stiffer on the head and knees,

Unaffected, indistinct,

indestructible and mediocre,

Sans genie et sans esprit!15

Nietzsche's utopia is that there will one day be “superhumans” who, like unAugustinian, unplatonic aliens, untragically and cheerfully, with all knowledge of the abysses, inhabit the earth and revive each other with “compassion,” light years away from all Aryan antics of strength. Instead of heading off to distant stars, it's about becoming a star yourself. “Let it shine! “(Peter Rühmkorf) Earth becomes a learning star, as a training camp for a planetary spirit. In solar humanism, humans become the sun, for themselves and others. As the earth's sunshine, bright lives then paradoxically fulfill the Christian mandate from Matthew 5 to be the “light of the earth.” Her yes to life is combined with the certain will never to live on the ascetic star again:

Why should he go back down into those murky waters where you have to swim and wade and make his wings look out of color! — No! It is too difficult for us to live there: What can we do for the fact that we were born for the air, the pure air, we rivals the ray of light, and that we would prefer to ride on etheric dust, like him, and not from The Sun away but to The Sunshine out! But we can't do that: — so we want to do what we can only do: The terra light Bring “that light The terra“be! ”16

Without such solar reconnaissance, all space expeditions — which is not difficult to predict — will only ever export the toxic imprints of the “spirit of gravity” until they freeze to death “under the flakes of demarcated space.”17. Space travel is ill-fated without anti-stress reconnaissance. Only stars can travel to the stars. Because they know what they want, their will has fewer toxic side effects:

Slowly matted down to the crown;

Failures are undeniable anymore.

And you know exactly what you want:

Once you happen correctly —18

sources

Adorno, Theodor W.: Mahler. A musical physiognomy. In: Collected Writings Vol. 13 Frankfurt am Main 1971, pp. 149—319.

image sources

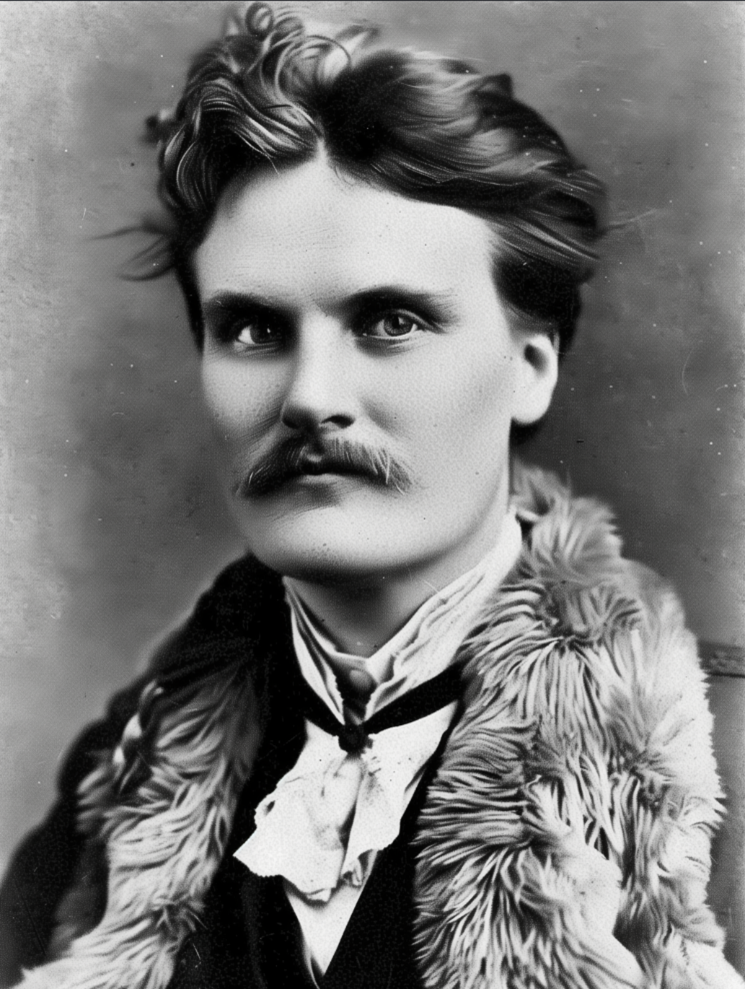

Article image: Sepdet (2018), source: https://www.deviantart.com/sepdet/art/Jurij-Gagarin-743180694

Figure 1: fiyonk14 (2020), source: https://www.deviantart.com/fiyonk14/art/Yuri-Gagarin-837583118

Figure 2: V.Vizu (2008), source: Wikimedia

Figure 3: NASA/Stephanie Stoll (2016), source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasa2explore/26685986293/

footnotes

1: Cf. So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 3.

2: According to legend, a Thracian maid mocked the first Western philosopher, Thales, for falling into a well while observing the fascinating stars.

5: Editor's note: From ancient Greek Ephemeros; lasting only one day, ephemeral.

6: Adorno, Mahler, p. 296 f.

7: Editor's note: “Gnosis” means the conviction that the world in which we live is not the creation of God, but of a subordinate, vicious “demiurge.”

8: Ibid., p. 297.

9: On the genealogy of morality, 3rd abh, paragraph 11.

10: Cf. So Zarathustra spoke, The spirit of gravity.

11: Editor's note: In addition to the first advent of Christ, the term “Advent” describes his return.

12: Beyond good and evil, Aph 230.

13: The happy science, Aph 107.

14: Cf. The happy science Aph 109.

15: Beyond good and evil, Aph 228.

16: The happy science, Aph 293.

17: Adorno, see above

18: Rühmkorf, “Let it shine! ”