Amor fati — A Guide and Its Failure

Reflections between Adorno, Nietzsche, and Deleuze

Amor fati — A Guide and Its Failure

Reflections between Adorno, Nietzsche, and Deleuze

This article attempts to approach two of Nietzsche's most puzzling ideas: the Eternal Return and Amor fati, the “love of fate.” How exactly are these ideas to be understood — and above all: What do they have to tell us? How can we not only affirm fate, which is interpreted as an eternal return, but really love learn?

Among the philosophers, it was in particular the “main philosopher” of the Institute for Social Research, Theodor W. Adorno (1903-1969), who was skeptical or negative of these ideas of Nietzsche. Where remains, from the point of view of Amor fati, of critique and utopia whose banner Adorno and his intellectual companions held up?

As a result of the general failure of Marxisms to deal with fascism theoretically, the Frankfurt Institute tried to reorient itself from the 1930s onwards. The success of this movement seemed understandable to many unorthodox Marxists not only on the basis of economic laws; in their opinion, greater consideration was needed of the “subjective factor,” i.e. the psychological structure of the bourgeois individual. As part of this paradigm shift, Adorno turned to Sigmund Freud as well as Nietzsche. For the rest of his work, the German philosopher was a recurring point of reference for him.

Adorno, however, remained stubborn towards Nietzsche in an aspect that is typical of Marxist Nietzsche interpreters time and again: the insistence on the orientation towards a state of redemption for humanity in some way — the anticipation of which is manifested above all in the devaluation of the present. From this point of view, he also criticizes in his main aphoristic work Minima Moralia (1951) — according to him, a “sad science [...] of the right life”1 — Nietzsche's concept of Amor fati. Nietzsche's will to “just be a yes-sayer at some point”2, he thinks is a kind of Stockholm syndrome in the philosophy of life. However, such a task — not only of affirmation, but even of the will to affirm — would amount to abandoning the basis for every living appropriation of Nietzsche's philosophy. Taking up Adorno's critique, with reference to the interpretation of the important French Nietzsche interpreter Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995), it is intended to explore what Nietzsche provides for the universal and yet always very personal question of why existence — here and now — wants to be affirmed.

I. Do We Want the Eternal Return?

Nietzsche's practical philosophy is often somewhat baffled. Amor Fati, Eternal Recurrence — What is that? What should you not only endure from (quasi-) imperatives such as “the necessary, [...] but love! ”3, “I just want to be a yes-man someday! ”4 and the question “Do you want to do this again and countless times? ”5 start? How are you supposed to make yourself want something if you don't want it? Reasons could at best establish that something is “necessary” and would be “accepted” as such — but love? In Zarathustra The “cripples” ask the protagonist of the book how they too could be convinced of his teaching. Nietzsche's “prophet” “answers” them by stringing together questions: “And who learned him [the will] reconciliation over time, and is higher than all reconciliation? [...] Who also taught him to want to go back? ”6 In other writings, Nietzsche does not become more direct in this regard: “[W] e would you have to be good for yourself and life to ask for nothing more than this last eternal confirmation and sealing? ”7 This lack of answers can be frustrating and gradually feels like a dead end.

And yet the Eternal Return in particular continues to develop a very natural appeal and an intuitive understanding of what is at stake here. Isn't it amazing that it's somehow understandable what the cryptic metaphor of the Eternal Return is about, even though it seems insoluble as a problem? Why don't you reject them as ludicrous or don't even understand what that's supposed to do? What is actually surprising is not the insolubility of the problem of eternal return, but that we still understand it, do not let go of it. It is precisely because we understand the problem (and possibly the answer as well) that anything can be done with the problems and frustrations that arise when trying to conceptually describe what this is about.

So why? I mean that the Eternal Return doesn't really teach us anything. It gains this natural appeal from its response to what we already have and understand within ourselves. Anyone who cannot accept the past, present or future cannot want their life to repeat itself forever. But this is precisely the germ of a Amor Fati who wants to affirm the Eternal Return. All negations are filled with the desire to answer in the affirmative. We know that the negation doesn't want itself. Although we can postpone it as a state of affairs, we only endure it. We feel that we should really fully develop the will to affirm. Otherwise, we would not be baffled by the problem of how to want the Eternal Return — we would reject the request as pointless and would not even be faced with a problem at all. As a matter of course, you would come to terms with a situation.

But for now, we find ourselves in a funny space between affirmation (of another state yet to be achieved) and acceptance (of the current state in its facticity) when we deny a state of affairs. For this reason and as a result, the Eternal Return motivates us. It shows that a state of negation or even just of yielding does not want itself (recurring). There is therefore a will for a state of affirmation which makes the affirmation of the Eternal Return perceived as a promise and as a problem — because it is simply not yet capable of reaching such a state. But how do you get there?

It is clear that you should not accept some things, but other times you should still refrain from unrealistic expectations. But it is so difficult to judge here; fundamentally, this question makes you rummage within yourself: What hopes do you release yourself from... and which hopes should you also fight through despair? Often enough, you should persist with the latter against “common sense,” which can only ever be limited to what can be said, imagined, felt here and now. “The fact that you despair is much to honor. For you did not learn how to surrender.”8, says Zarathustra to the “higher people.” Because “[a] ll that suffers wants to live, that it becomes mature and funny and longing — longing for something more distant, higher, brighter. ”9 Only when you keep up the bar of hope against the now can the pressure of “Woe speaks: Go away! Go away you woe! “(ibid.) turn against the world and yourself and create something in which the once uncertain “yes” of former hope completely unfolds.

If at some point you just want to be a yes-man and want the eternal return but can't, it can't be a question of finding a general answer and solution. What prevents you from saying yes? You have to ask the question of who you are. You won't find a ready answer — you can only give the answer by becoming it. In this way, the question of how you can want the eternal return of your existence falls apart.

But the insight that you shouldn't look for the answer doesn't solve the question yet. How can you assess which claim should be maintained and which should be abandoned or modified? And how should one know whether such doubts should not also be attacked against Amor Fati? Are there not conditions that should be denied, even if you cannot work towards changing them?

II. Adorno's Criticism of Nietzsche's Amor Fati

That is exactly what Adorno asks: “And it would probably be the question to ask whether there is any more reason to love what happens to you, to affirm what is there because it is than to believe what you hope for to be true. ”10 Especially in conditions of incarceration, when you can no longer defend yourself against the circumstances, the will to assert yourself would turn against your own indignation and claims so that you could at least somehow assert yourself: “[S] o you could find the origin of Amor Fati in prison. People who no longer see and have nothing else to love fall in love with stone walls and barred windows.” (ibid.) If you can't rely on the fact that you should live up to the need to become a yes-man — then what can you rely on? “In the end, hope is how it escapes reality by negating it, the only form in which truth appears. Without hope, the idea of truth would be hard to think about” (ibid.). Although it sounds similar for now, Adorno gives a radically different answer than Nietzsche. It is not the here and now that would be answered in the affirmative, but in favour of the affirmation of something that may be unreachable, a hope.

It was stated above that with Nietzsche, practical philosophy is based on the task: Existence requires to be answered in the affirmative. Is there anything truer? Something more important? That is now threatening to slip away again. How could an argument be made against Adorno here? On what basis can you still judge here?

For now, a step back again. Adorno writes that it is hope that reveals the view of truth. It would therefore not be the case, as is usually thought, that the cool and realistic look would make it clear what was right — for example, the subsequent, negating hope or Nietzsche's affirmation. It is exactly the other way around: hope first, then truth. You would then probably recognize that you are deluding yourself with Amor Fati and not with negating hope.

This appears as and is a self-fulfilling line of argument. But let us not dismiss them by wishing back the deceptive certainty of a supposedly objective look, which would clear the truth just by thinking really seriously. Let's just let ourselves fall. What can then be countered with Nietzsche Adorno? Are we finding a new reason on which it can be proven that the task of existence is to affirm oneself and the Eternal Return must be affirmed?

III. The Impossibility of an Objective Evaluation of Life

Nietzsche also knows that there is no objective reason for judging life: “[E] in drive without a kind of discerning assessment of the value of the goal does not exist in humans. ”11 And in the event that life makes judgement about life, you must therefore bear in mind that here an assessment can only ever show how it appears to itself. It is important to “grasp this amazing finesse that the value of life cannot be estimated. Not from a living person, because such a party is an object of dispute and not a judge.”12. As a result, such judgments “only have value as symptoms” (ibid.).

Now you can avoid the intrusiveness of Adorno's argument that hope — the perspective of a better world — would somehow be more true. But there is also nothing left. All settings open up perspectives in which they then appear to be the right one for each case. We can't trust anyone that she's really the real one now. The question of whether life and eternal return must be answered in the affirmative now seems pointless. A swarm of different urges. And they either say yes to life — or they just don't. The question of how the Eternal Return can be answered in the affirmative now seems almost embarrassing. What should any guidance be based on? We all fall back on ourselves—to who we are, where there is nothing to praise, reprimand, or argue about.

In Human, all-too-human Nietzsche also doesn't know how to navigate any further when he hits on this determinism: “I believe the decision about the aftermath of knowledge is made by the temperament given by a person”13. In Nietzsche's confrontation with this complex, people's existence thus appears questionable. The bottom line is that life creates more suffering than pleasure and the fact that people stuck to life is due to their instincts. But something must have changed in Nietzsche's thinking that, in this initial situation, he found something that made him portray the Eternal Return as something to be wanted. What did Nietzsche understand and why doesn't he simply share it with you? And how can you ask for it?

IV. Why the Will is Affirmative...

At this point, I want to turn the problem around: What did you actually hope to get from getting an answer? A theoretical answer, which could make you understand the necessity, would therefore compel you. Or should it be a secret whose hearing transforms us, as it were, in order to become what we actually want to be? It has the taste of self-abandonment to hope that the necessity would be able to impose on you what you were unable to do yourself. The reasonably perceived need may give rise to “its essence for any purpose Roll off”14 If you could, you would be tired of this responsibility yourself. Honestly speaking, however, there is still a whole separate space of consideration where self-respect does not allow us to simply surrender to what is necessary, even if there is nothing to counter it. It also looks quite funny when Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), for example, sees Nietzsche's Amor Fati as a simple identification with what is necessary: “Obviously, it is not about changing the world or people, but about 'evaluating' them.” A transformation that would consist in the “psychologically highly effective trick,”to want, which is happening anyway. ”15 In this way, the wish to be a yes-sayer would lead the will to silence in order to look away from everything to the negative.16 Such self-reliance is a simple matter and is not worth much simply because it costs a lot. But we really don't just want to endure “[d] what is necessary, [...] but love...”17. And would such a manifestation of the world's love for itself turn away from its denials? Or does real self-love not also include one's own growing pains?

The affirmation of the Eternal Return must therefore be something that comes out from within us for no reason. Why say yes? Why say yes to anything at all? Because all will has always been an affirmation! That “the will to power is not a being, not a becoming, but a pathos [is] the most elementary fact that results in becoming, having an effect...”18. Pathos: This means a force, a movement, an interpretation of the world and its change. Yet there is not one thing that wants to change anything. Change is what exists as a will. Or as Deleuze says: “Power is That, what willingly. ”19 The will “does not seek, it does not desire, and above all it does not desire power. He giveth”20. But he doesn't pass it on to anyone: The will to power is a diverse, ever-renewing gift of affirmation to oneself. For Nietzsche, this circumstance is expressed in a person in such a way that in him what is commanding and obedient at the same time: “Freedom of will — that is the word for that multiple state of pleasure of the willing person who commands and at the same time sets himself as one with the performer.”21. There is nothing upstream in humans that could decide; a balance is only a symptom, for example, of an unfinished battle of different wills. Asking the question why the will is affirmative is therefore ignoring the will. Affirmation is not an optional state of will; it is its necessary mode of existence. Affirmation certainly not as an accounting judgment, but as a way of being. Every will, as long as it exists, stands firm against influences, resistance and time. His affirmation does not have to be an emphatic thanksgiving. His affirmation is his own, always unfounded maintenance and improvement, which creates the basis for judgment and evaluation in the first place. Nor is such an affirmation about happiness or absence of suffering. Nietzsche writes of pessimism that it “absolutely does not have to be a theory of happiness: by triggering strength that was squeezed and accumulated to the point of torment, Does she bring luck. ”22 That latter happiness is the affirmation of being and doing what you have to be and do.

V.... and Why People Say No

Whether you follow me at this point or not, such a point of view gets ridiculous at second glance. Human conditions are known, observable or imaginable which do not seem alien to themselves, but which grieve the world that this has happened. Situations in which you wish things had happened differently. This makes it look like there is a general standpoint of judgment from which we deplore our specific ego and, as it were, do not affirm it. That should not be denied. But it is that “second look” at existence that can make existence questionable for us. For a “first glance,” however, the question of affirmation cannot arise at all, because the concrete will has always been an immanent affirmation. As we imagine it with animals, only the first look — which makes everything impossible beyond affirmation — comes into consideration.

The affirmation of the Eternal Return at the level of second glance is the affirmation of the whole, of the great coincidence that existence exists in general and in its present form. Again: It is of no use to interpret one's own concrete being, the world, or the whole as necessary in this form. Not only can this not produce love, you also deceive yourself that nothing is completely necessary in the last resort, because the existence of the whole thing can only be understood as a coincidence. Deleuze writes:

For the eternal return is the return differentiated from progress, is the contemplation different from progress, but also the return of progress itself and the return of action [...].23

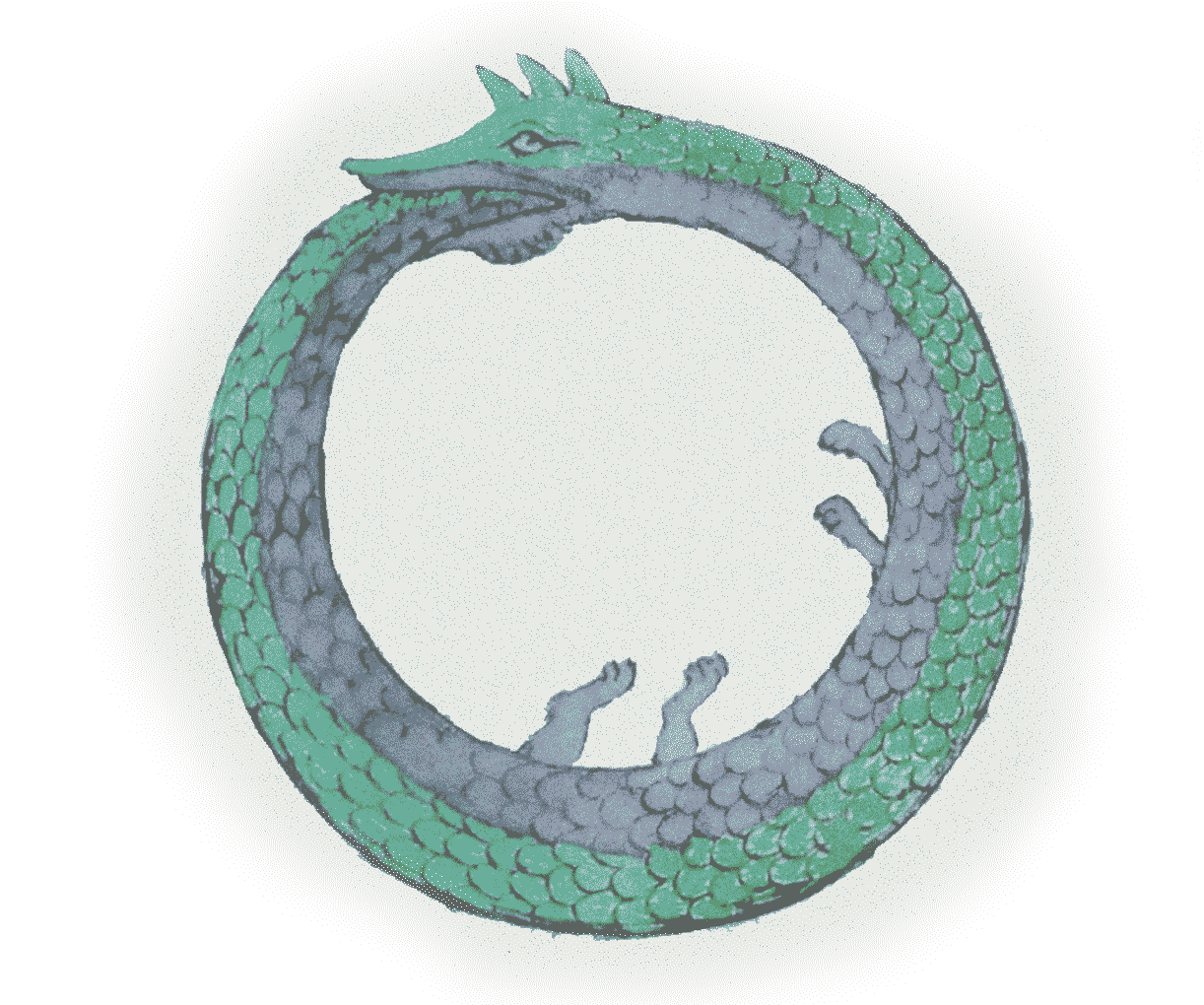

He imagines a child immersed in his game who also delights when he takes a step back and then feels like playing again. Such a second affirmation is therefore needed. Even on this second level, it cannot be about theoretical insights, no imperative. Just as naturally as every individual will wants himself on the first level, the person of Amor Fati will want the whole thing and also in that respect “the eternal pleasure of becoming self [...] being”24. So how to answer in the affirmative? No explanation does the work. Nietzsche's cocky descriptions of bravely saying yes in the midst of all suffering have their charm, but then they also exhaust themselves. Once again, it helps to ask why it doesn't actually work. That brings us to the problem of resentment25.

VI. What Does Resentment Want?

It has often been described how low the resentment is that it harms everyone involved. But you can also try to understand the resentment. The word “resentment” is a substantiation of “to feel again.” You can understand it as the fact of not being able to let go of a feeling — or better yet: that a feeling cannot let go of itself. This happens during experiences of loss, insults, and disappointment. Why does this happen to us so often? With regard to the “fight [it] for life,” Nietzsche accuses Darwin of having forgotten the mind; the weak repeatedly reaches for the spirit in order to master the strong.26 Instead, the human imagination gives all our pain the means not to have to go into catharsis, the spiritual purification, but to survive or even to dominate. It is therefore too easy for us not to have to admit that something is over or never existed and to live through the full severity of the loss. Instead, we can ask again and again: “Why me? ”, “Why hasn't this person decided otherwise? ”, “Why are people and the world like this? ”. But in their will to power, such feelings become even more creative; unfortunately, the imagination has no limits. Didn't Adorno, with his standpoint of hope, give an interpretation of the world within which it is good to suffer from the world as it is, because in it there is another world accessible through hope, which is the true one? But we all practice the little moralisms in our everyday lives through which we do not let the world, others and ourselves be as they are. Or we accuse them of being bad because they're not what we wanted them to be. What's all this for? It is usually not a question of recovering a beloved object that would redeem. There is only the pain that is constantly reinterpreted, that should also be done to others, acknowledged or felt again. By creating a world in which it is right to suffer for yourself and the world, resentment blocks every exit. In this way, it can survive as a will that in a certain way does not want itself because the catharsis has only been postponed — and yet cannot let go. Like a broken record, the same track plays out over and over again.

All of this puts people in a questionable aspect. A will that keeps itself alive — and would actually rather not be? This is what is manifested in resentment and articulated in the inability to affirm the Eternal Return. Wanting, you could want your own return, but still remain something that does not want to repeat yourself and the world — what is that actually supposed to be? In the main, we can't do anything about it. At the “Try [...] Man”27 Is “[d] he consciousness [...] the last and latest development of the organic and therefore also the most incomplete and ineffective about it. Countless mistakes originate from consciousness, which cause an animal, a human, to perish.”28. Far too many opportunities give us the awareness and imagination to postpone the pain of fatality a bit without knowing what impasse we are entering. When we first ask, both large and small, “Why this way... and not something else? “If we go somewhere else, we certainly don't stick to fate; this is how an Amor Fati becomes more and more alien to us. “Why is the world so and so? ”, “That person could have made a different decision! “— Such thoughts do not remain thoughts. They create a new, imaginary world, we then feel in it, we feel it. But it is a steep path away from the world which must be answered in the affirmative.

VII. Who Overcomes Resentment and How?

What next? “Will — that is the name of the liberator and the bringer of joy”29. But we still have the “half-will”30 and are not “[s] olks who can want to”31. The “human attempt” is not responsible for ending up in an awkward impasse — in fact, she is himself. However, this should not give rise to a blunt desire to return to a time before consciousness. The traces have already been blurred and everything that could possibly be desired — that is simply not who we are anymore. But the fact that we are not responsible for our situation does not mean that we cannot take responsibility for ourselves here and now. In fact, another direction is emerging: no return, no leisurely furnishing, but a merciless and welcoming consideration of what has actually happened to us in our existence — and a whole will to do so again. Because we cannot lean back on nature, but must regard and perceive ourselves as a piece of new nature, Nietzsche speaks of his naturalism as “coming up” into nature instead of returning.32 In the case discussed here, coming up in nature means: Affirming existence without deception and with full awareness on the said second level, i.e. affirming the big picture and wanting to repeat our role in it. But we're not there yet. First, we need compassion for the part of us that doesn't want to return. In Zarathustra It says: “But all immaturity wants to live: woe! ”33 The resentment persists in the space between wanting to continue and not wanting more. There is nothing concrete that it can want more from the world; it simply persists in any hope of redemption. Once again, it says: “What was perfect, all maturity — wants to die! ”34 This applies not only to all affirmative wishes, which like to be inherited by new affirmations. However, there can also be perfection for suffering:

Everything that suffers wants to live, mature and funny and longing — longing for something more distant, higher, brighter. “I want heirs, so says everything who suffers, I want children, I don't want myself”.35

All the suffering in resentment is not in any way degenerate and must be recklessly rejected. Instead, there can be an understanding and agreement. Resentment itself is still part of the nature that wants to rise up and be inherited. Was it not what was waiting for when the suffering of farewell was still too blunt? And wasn't it precisely the resentment that insisted that the Eternal Return was something to be affirmative? An oh-so-masculine conduct of will is not enough here; Zarathustra also knows that: “Woe says: 'Break, bleed, heart! Walk, leg! Wings, fly! Inan! Get up! pain! 'Well! Well done! Oh my old heart: Woe says: Go away!”36 The resentment that, looking at itself, understands that it should and wants to pass away and only had to gather the strength to do so — that is also ourselves! There is no subject behind this who could calculate anything. The “Vergeh! “, which a pain speaks to oneself, can only be an intrinsically motivated journey into nothingness, behind which there is nothing more waiting: no justification, no rebirth, no redemption. How can that be wanted? How can an eternal return still be wanted here? This cannot be about a necessity, but only a matter of course: “Pain is also a pleasure”37. And those affected in this way would speak to pain: “[V] go, but come back! ”38 Such pleasure does not want the offense as something that could be quickly put behind. By wanting the becoming and the whole, she also wants such offense with unconditional “yes” and recurring forever. “[S] he is thirstier, heartier, hungrier, more terrible, more secret than anything hurt, she wants yourself, she bites into yourself, the will of the ring wrestles with her —”39. Something like that happens or not. In any case, there are no reasons and any further justification would be misplaced.

If we followed Adorno in saying that only hope would open up the perspective of truth, we would limit ourselves. Would that be the whole truth? A truth limited by what we can and must hope for in the here and now? Nietzsche, on the other hand, tries to open his mind to the possibility of love that goes beyond us. In such love, the fatal, actual world is not longed for, asked away or hoped away. But it is not a selfless sacrifice to fate. Precisely by not accusing the world, it gives us the space to express our suffering and despair directly. Like any mature love, however, such self-love does not retain its object but liberates, shows us that we do not have to be limited to what we want, that we are not and do not want to be an end. Such love, in that it is the pleasure of creating, becoming and passing away that we are, makes us become something that will one day continue to arrive in the world and be at home. If we set ourselves up to the eternal desire to be ourselves and push it ever higher and farther, the question of Amor Fati also dissolves into a matter of course.

Moritz Pliska (born 1999) studies sociology and philosophy in Kiel. There he tries to be a good epistemological experiment for himself.

Sources

Adorno, Theodore: Minima Moralia. Reflections from damaged life. Frankfurt am Main 1951.

Arendt, Hannah: Of the life of the mind. Thinking, Wanting. Berlin & Munich 1979.

Deleuze, Gilles: Nietzsche and philosophy. Hamburg 1991.

Footnotes

1: Adorno, Minima Moralia, P. 13 (Assignment).

2: The happy science, Aph 276.

3: Ecce homo, WArum I am so clever, paragraph 10.

4: The happy science, Aph 276.

5: The happy science, Aph 341.

6: So Zarathustra spoke, Of redemption.

7: The happy science, Aph 341.

8: So Zarathustra spoke, From the higher person, 3.

9: So Zarathustra spoke, The Nightwalker Song, 9.

10: Adorno, Minima Moralia, p. 110 (Aph. 61).

11: Human, all-too-human Vol. I, Aph 32.

12: Götzen-Dämmerung, The problem of Socrates, paragraph 2

13: Human, all-too-human Vol. I, Aph 34.

14: Götzen-Dämmerung, The Four Great Mistakes, paragraph 8.

15: Arendt, On the life of the mind, P. 398.

16: See ibid., p. 400.

17: Ecce homo, Why I'm so smart, paragraph 10.

18: Subsequent fragments No. 1888, 14 [79].

19: Deleuze, Nietzsche and philosophy, P. 93.

20: Ibid., 94.

21: Beyond good and evil, Aph 19.

22: Subsequent fragments No. 1887, 11 [38].

23: Deleuze, Nietzsche and philosophy, P. 30.

24: Ecce Homo, The birth of tragedy, paragraph 3.

25: Editor's note: This year's Kingfisher Prize for Radical Essay Writing is also dedicated to the problem of resentment and its topicality (link).

26: Cf. Götzen-Dämmerung, Journeys of an Out-of-Date, Aph 14.

27: So Zarathustra spoke, Of the gifting virtue, 2.

28: The happy science, Aph 11.

29: So Zarathustra spoke, Of redemption.

30: So Zarathustra spoke, On the diminishing virtue, 3.

31: Ibid.

32: Cf. Götzen-Dämmerung, Journeys of an Out-of-Date, Aph 48.

33: So Zarathustra spoke, The Nightwalker Song, paragraph 9.

34: Ibid.

35: Ibid.

36: Ibid.

37: So Zarathustra spoke, The Nightwalker Song, paragraph 10.

38: Ibid.

39: Ibid.

.jpg)