„Friede mit dem Islam“?

Wanderungen mit Nietzsche durch Glasgows muslimischen Süden: Teil 1

„Friede mit dem Islam“?

Wanderungen mit Nietzsche durch Glasgows muslimischen Süden: Teil 1

In dem vorerst letzten Beitrag unserer Reihe „Wanderungen mit Nietzsche“ (Link) begibt sich unser Stammautor Henry Holland in eine für die meisten von uns unbekannte Welt. Er begab sich im Spätsommer zu Fuß in den muslimisch geprägten Süden der schottischen Großstadt Glasgow, um dort zwischen Charity-Shops, Moscheen, Buchläden und Restaurants mit den Bewohnern des Viertels ins Gespräch zu kommen und zu erkunden, wie es um den heutigen westlichen Islam bestellt: Wie ticken heutige in Europa lebende Muslime? Wie verstehen sie den Islam? Inwieweit sind sie in die säkulare britische Gesellschaft integriert? Und können Nietzsches Gedanken dabei helfen, ihre Perspektive besser zu verstehen?

Am Anfang seines Zweiteilers gibt Holland zunächst einen kurzen Einblick in den Forschungsstand zu Nietzsches Auseinandersetzung mit dem Islam und seiner Aneignung in der muslimischen Welt. Er berichtet dann über einen Vortrag von Timothy Winter über den französischen Theoretiker und Künstler Pierre Klossowski und dessen Verhältnis zum Bekenntnis Mohammeds. Diese Vorlesung war es, die ihn dazu inspirierte, diese Reise zu unternehmen, die ihn mitten in eines der meistdiskutierten Themen im Europa unserer Gegenwart führte: „Sag, wie hast du’s mit der Religion des Propheten?“ Der Artikel schließt mit dem Beginn seiner Aufzeichnungen.

Aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Lukas Meisner. Zum englischen Originaltext.

I. Vorbereitende Spaziergänge

Ich habe es dem Herausgeber dieses Blogs zu verdanken, dass er, als er nach Essays zu Nietzsches programmatischer Liebe zum Wandern fragte, meinen Vorschlag von Stadtspaziergängen, zu diesem Zeitpunkt noch ungelaufen, unter Muslimen in Südglasgow und evangelikalen Christen in London nicht sogleich zurückwies. Als ich den ersten dieser beiden Spaziergänge unternahm und dessen Reisetagebuch schrieb, erwies sich die islamische Dimension als so faszinierend, dass allein daraus ein zweiteiliger Artikel entstand; die evangelikalen Christen müssen sich damit auf den Seiten meines Notizbuchs gedulden, bis die Zeit für ihre Veröffentlichung reif ist.1

Wie auch andere Nietzsche-Forscher, so weiß mein Herausgeber, dass es zahlreiche Berührungspunkte zwischen Nietzsche und dem Islam gibt, die von denjenigen, die sich beruflich mit dem Philosophen beschäftigen, jedoch gewöhnlich gemieden werden. Ian Almonds hervorragende und kurze Einführung in dieses Feld, die diesen Trend ändern möchte, stellt fest, dass zum Thema im Jahr 2003 „trotz gut über einhundert Referenzen auf den Islam und islamische Kulturen ([den persischen Dichter Hafiz [ca. 1325-1390 u. Z.], Araber, Türken) in der Gesamtausgabe nicht eine einzige Monographie“ existierte.2 Selbst zum Zeitpunkt der Veröffentlichung konnte Almonds Behauptung eher der Tendenz nach als wörtlich genommen als korrekt gelten. Bereits der Artikel über Nietzsche und den berühmten Poeten Rumi aus dem 13. Jahrhundert, der 1917 vom indisch-muslimischen Philosophen und Dichter Muhammad Iqbal publiziert wurde, stellt eine Studie dar, die sich eingehend mit dem befasst, was der Islam und Nietzsche voneinander gelernt haben. Iqbal verfasste dieses Werk derweil zum Erreichen bestimmter Ziele, nämlich um Nietzsche einem breiteren muslimischen Leserkreis vorzustellen sowie zur Belebung einer antinihilistischen Version des Sufismus.3 Er kann nicht die objektive Vogelperspektive bieten, die Almond mit seinem Beitrag zu fördern versucht. Lobenswert ist, dass Peter Adamson in seiner derzeit achtbändigen Geschichte der Philosophie mehr als 500 Seiten dem Komplex „Philosophie in der islamischen Welt“ widmet. Trotz des totalisierenden Untertitels der Serie – „eine Geschichte ohne jedwede Lücken“ – offenbaren sich gähnende Löcher rund um Nietzsches pulsierendes Werk. Die einzige Referenz, die Adamson bereitstellt, ist Iqbals Bekenntnis zum preußisch aufgewachsenen, später staatenlosen Denker zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts. Wenigstens Roy Ahmad Jacksons Nietzsche and Islam (2007) sollte, seiner Imperfektionen ungeachtet, hier Erwähnung finden, ebenso wie Peter Groffs scharfsinnige Antwort darauf (2010).

Da ich meinerseits eine Ethnografie einer Straße verfassen möchte, die von äußeren Verdächtigungen gesäumt ist, ist es am besten, wenn ich meine Vorbehalte offenlege und meine Position klarstelle. Ich bin ein schottischer weißer Nicht-Muslim; ein Agno-Atheist4, doch unzufrieden damit und daher notorisch flirtend mit dem Glauben, auch wenn meine Wellen des Glaubens in immer kürzeren Abständen zu kommen und zu gehen scheinen. Wie sehr ich mich auch bemühe, ich schaffe es nicht, echte Frömmigkeit auszustrahlen: Wenn ich mich gelegentlich mit Zeugen Jehovas unterhalte, machen sie sich einmal nicht die Mühe, mir ihre Bekehrungsrede zu halten, als würden sie spüren, dass ich reine Zeitverschwendung bin. Seit ich mit viereinhalb Jahren in Edinburgh in die Grundschule kam, blieb der Anteil der Muslime in meiner Klasse in den nächsten sieben Jahren stabil bei etwa fünfundzwanzig Prozent: Shiraz, Asharif, Zahir, Samir und ein einziges Mädchen, Javeria, waren die Menschen hinter dieser Statistik.5 Wir, und ja, die weißen schottischen Kinder fühlten sich wie ein „Wir“, spielten fast täglich mit den muslimischen Jungen auf dem Spielplatz Fußball, wobei die Mannschaften natürlich ausschließlich nach ihren Fähigkeiten ausgewählt wurden, und ich erinnere mich an mindestens eine Einladung zu Zahirs Geburtstagsparty. Aber in den letzten Jahren der Grundschule hatte sich meine Freundesgruppe auf drei oder vier andere nicht-muslimische, weiße schottische Jungen reduziert. Diese unsichtbare Barriere war ebenso sehr durch die Klasse wie durch Religion oder Hautfarbe entstanden. Unsere Schule lag, wo der östliche Rand der neoklassizistischen Neustadt Edinburghs mit ihrer selbstbewussten Mittelschicht auf den westlichen Rand der damaligen Arbeiterviertel Bonnington und Leith traf: Die muslimischen Kinder, die ich kannte, wuchsen größtenteils dort auf, in Arbeiterfamilien. Ich habe heute zu keinem von ihnen mehr Kontakt, aber diesen Menschen habe ich es zu verdanken, dass ich keine Angst vor dem Islam habe. Denn die unaufhörlichen Trommelschläge der extremen Rechten, dass die muslimische Kultur in den kommenden Jahrzehnten die nicht-muslimische Kultur überschwemmen werde – das Geschwätz über Scharia-Diktaturen, die es in Europa angeblich schon gibt, muss ich gar nicht erst wiederholen –, erregen zwar meine Aufmerksamkeit, können mich aber nicht überzeugen.

Bei solchen Kulturkämpfen geht es sicherlich nicht um demografische Fakten, die schwer zu bestreiten sind, sondern um die religiösen Identitäten und die politischen Absichten, mit denen diese Fakten verbunden sind. Wie Ed Husain in seinem Buch Among the Mosques feststellt – einem besorgten Alarmruf eines liberalen Muslims an die Politik über den Zustand des „muslimischen Großbritanniens“ heute –, wuchs die muslimische Bevölkerung Englands in den fünfzehn Jahren bis 2016, in denen die Gesamtbevölkerung Englands um etwa elf Prozent zunahm, fast zehnmal so schnell.6 Die Muslime in Schottland sind zahlenmäßig stärker marginalisiert als im übrigen Großbritannien, da sie etwa einen von 70 Einwohnern ‚Albas‘7 ausmachen, verglichen mit etwa einem von 20 Einwohnern der Gesamtbevölkerung des Vereinigten Königreichs. Dennoch bedeutet die im Vergleich zu nicht-muslimischen Bevölkerungsgruppen höhere Geburtenrate der muslimischen Bevölkerung8, dass die Zahl der Muslime in allen Teilen des Vereinigten Königreichs weiter steigen wird, wobei bis 2031 in einigen Londoner Stadtbezirken und Gebieten von Birmingham, Leicester, Bradford und mehreren anderen englischen Städten eine muslimische Mehrheit erwartet wird.9 In Schottland wird dies erst in einigen Jahrzehnten der Fall sein, aber bereits jetzt ist beispielsweise mehr als jeder vierte Einwohner des Wahlbezirks Pollokshields im Süden von Glasgow ein Moslem.10 Deshalb beschließe ich, meine Wanderung nach Pollokshields und Umgebung zu unternehmen. Diese Reise ist eher durch Statistiken motiviert als durch persönliche Beweggründe. Mein Wunsch, aus erster Hand zu erfahren, wie die Muslime in Glasgow die Welt sehen, verbindet sich mit einer unerwarteten Begegnung auf YouTube und veranlasst mich, den Zug um 9:45 Uhr von Edinburgh Waverly nach Glasgow Queen Street zu nehmen.

II. Lektüre vor der Wanderung

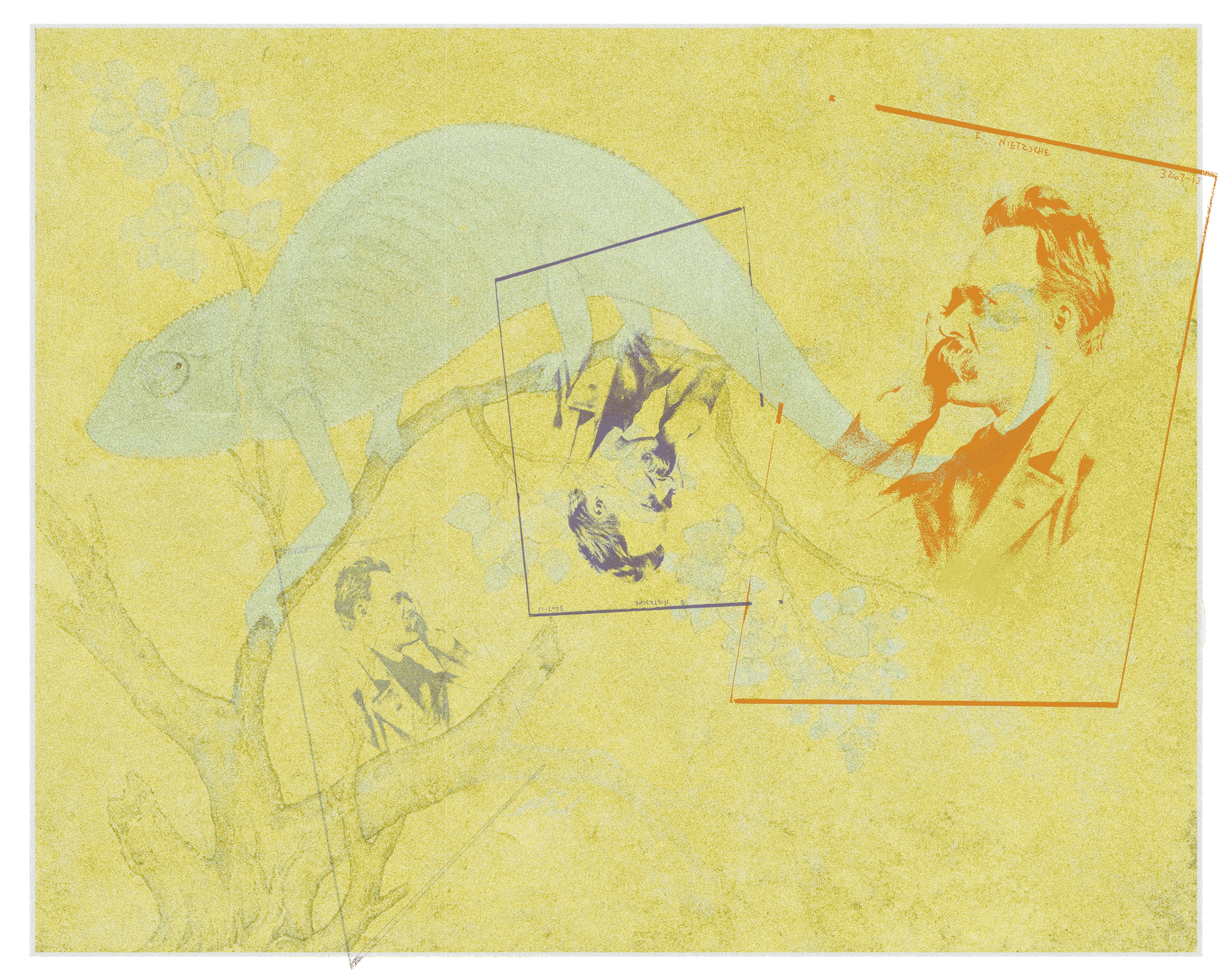

or etwa einem Jahr tauchte in meinem Feed, der wie üblich von reißerischen Überschriften und Indie-Bands der 1990er Jahre geflutet worden war, etwas auf, von dessen Existenz ich bislang nichts wusste: eine aktuelle Keynote-Vorlesung von Prof. Timothy Winter – alias Abdal Hakim Murad – über Pierre Klossowskis „Nietzsche-Interpretation aus einer islamischen Perspektive“. Der Name Klossowski (1905–2001 u. Z.) dürfte denjenigen bekannt vorkommen, die sich wirklich für die französische Theorie begeistern. Als bildender Künstler und Autor trug er in den 1930er Jahren zur avantgardistischen Zeitschrift Acéphale unter der Leitung von Georges Bataille bei (dessen Philosophie in Jenny Kellners POParts-Artikel vorgestellt wurde). Später veranlasste sein 1969 erschienenes Buch Nietzsche und der Circulus vitiosus deus Foucault, Deleuze und andere Größen der Pariser Intellektuellenszene dazu, ihre Haltung gegenüber Nietzsche zu überdenken. Winters Umgang mit dem, was Klossowski und Nietzsche uns und einander erzählen, ist meisterhaft. Er taucht auf ansprechende Weise in das weite Feld der Theorie, des Modernismus, der Religion und der ethnisch geprägten Politik im Globalen Norden und in den kommenden Jahrhunderten ein und überlässt es den intellektuell weniger Begabten, d. h. den meisten von uns, das Kleingedruckte auszubuchstabieren.

In meiner persönlichen Vorstellung des Paris der Deleuze-Ära ist Klossowski eher wegen seiner künstlerischen als wegen seiner philosophischen Genealogie bemerkenswert. Er war der älteste Sohn der Malerin Baladine Klossowska, die den Anhängern der modernen Poesie als letzte Geliebte Rainer Maria Rilkes und Inspirationsquelle für sein spätes Meisterwerk Sonette an Orpheus bekannt ist. Sein jüngerer Bruder war der weitaus bekanntere Maler Balthus, dessen Gemälde heute im MoMA und in der Fondation Beyeler bei Basel hängen; obwohl er erst spät seinen Stil konsolidierte, scheint er seinen Platz im künstlerischen Kanon des 20. Jahrhunderts gefunden zu haben. „Balthus brillanter Bruder“11 muss dagegen noch seinen Platz finden. Obgleich Pierre Klossowski auch als Übersetzer beeindruckend war und die ersten französischen Übersetzungen von Werken Nietzsches, Benjamins und Heideggers verfasste, rangiert er in der Kulturgeschichte nach wie vor meist unter den Fußnoten. Wer ein Spezialist oder Theoretiker mit einer außergewöhnlichen Leidenschaft ist, hat sicher schon von Klossowski gehört; andernfalls gibt es kaum einen Grund, warum man ihn kennen sollte.

Wie Winters weitere Namen vermuten lassen, ist er zum Islam konvertiert; er hat sein gesamtes Erwachsenenleben in diesem Glauben verbracht: 1979 wurde er im Alter von neunzehn Jahren Muslim. Auch Klossowskis Konversion zum Islam im hohen Alter wird von Winter erwähnt; er beschreibt sie als „ein zweideutiges Ereignis, auch wenn es von seinem Bruder Balthus explizit bezeugt wird“.12 Es ist hierbei wichtig zu berücksichtigen, dass Ambiguität in Winters ikonoklastischer Sichtweise auf politische und religiöse aktuelle Ereignisse eine stark positive Konnotation hat. Aussagekräftiger als die Details von Klossowskis persönlichem Glauben sei, was er bezüglich der „Pathologie der modernen Subjektivität“ zu bieten habe, „entliehen zu einem hohen Grad einer ungewöhnlichen Vermählung von Nietzsche und der Heiligen Teresa von Ávila [1515-1582 u. Z.]“.13 Von hier aus wendet sich Winter dem zu, was viele Menschen im Westen als fast unheilbare Wunde und Verlust empfinden – und zeigt auf, wie Klossowski dabei helfen könnte, diese Wunde neu zu empfinden und zu denken. Er bedient sich dabei der Antinomien des Apollinischen und des Dionysischen, deren aus den Fugen geratenes Gleichgewicht Nietzsche in Die Geburt der Tragödie beklagt, und beruft sich auf die „höchst originelle Deutung“, welche Klossowski „Nietzsches Erfahrung der ewigen Wiederkunft“ gebe.14 Winters Diagnose der okzidentalen Malaise lohnt ein längeres Zitat:

Die Nativisten schlagen Alarm: In ganz Europa sind die Geburtenraten der Einheimischen im freien Fall. Wir dürfen dieses Phänomen als „Biopause“ bezeichnen, eine Entwicklung, die in zwei Schritten zu erfolgen scheint. Zuerst unterbricht die postindustrielle, sich säkularisierende Menschheit gewaltsam ihre Symbiose mit den Gliedern der Natur, was ihren rapiden Zusammenbruch bewirkt. Darauf folgt dann die Abkehr der Menschheit selbst von ihrer eigenen Reproduktion. Zerronnen ist die Hoffnung ihrer kalifornischen Vorreiter, die sexuelle Revolution der 1960er Jahre mit einer spirituellen zu verbinden, sie zu sakralisieren. Sie hat schlicht und ergreifend zu einer herabgesunkenen, zukunftslosen Triebhaftigkeit geführt. Das augustinische Ideal einer Fortpflanzung ohne Begehren wurde in sein genaues Gegenteil verkehrt. […] Eine ganze Flotte labiler Archen segelt diesem Europa der Biopause entgegen. An Bord sind Einwanderer, die meist das Mal Ismaels und Hagars tragen, dieser archetypischen Exilanten.15 Diese neuen Europäer legen nicht nur, was ihre Fertilität angeht, keine Biopause ein, sondern bleiben auch in ihren traditionellen Kulturen verwurzelt. Ihre Religiosität nimmt zu, wie der 15. Arabische Jugendreport16 in diesem Jahr nahelegt oder Michael Robbins vom Arab Barometer,17 der […] sagt, dass Jugendliche im Alter zwischen 18 und 29 Jahren an der Speerspitze einer „Rückkehr zur Religion“, die sich quer durch den Nahen Osten und Nordafrika in den letzten zehn Jahren vollzogen habe, stehen würden. Dem widersetzt sich trotzig Europas „ewige Rückkehr“ zu seiner Dichotomie zwischen Selbst und dem Anderen. Überall auf dem Kontinent schießen neue christlich angehauchten Nationalismen wie Pilze aus dem Boden, wir erleben die Wiederkunft einer chronischen Abwehrreaktion gegen die Semitismen: Apoll gegen Dionysos, das Lineare und Verschlossene gegen das Lebendige und Polymorphe – immer dieselbe Leier der europäischen Selbstdefinition seit den Tagen von Euripides. Doch immer mehr stellen sich James Baldwins Frage: Möchte ich wirklich in ein brennendes Haus integriert werden?18

Leser, die vermuten, dass ich für Winter Schleichwerbung mache, mögen seine Glaubwürdigkeit überprüfen. Engagierte Säkularisten könnten von dem, auf das sie stoßen, beunruhigt sein. Jacob Williams betrachtet Winters als einen zentralen Knotenpunkt „in dem [islamischen] traditionalistischen Netzwerk im Westen“, zusammen mit zwei weiteren Denkern, die ebenfalls zum Islam konvertiert sind: Hamza Yusuf (alias Mark Hanson) und Umar Faruq Abd-Allah (Larry Gene Weinman).19 Williams möchte die Beziehungen dieser Denker „zu unterschiedlichen Strömungen innerhalb des westlichen Denkens“ in ihrer Erklärung und Darstellung des Islam untersuchen und dabei aufzeigen, wie sich diese Denker zur „zur traditionalistischen Schule“ verhalten.20 Diese definiert er, in Übereinstimmung mit dem Mainstream der Forschung, als „westliche esoterische Bewegung, die René Guénon [1886-1951 u. Z.] ins Leben rief und die sich um die Wiedergewinnung einer spirituellen Weisheit bemüht, die sich in allen Religionen finde, doch in der Moderne verloren gegangen sei“21. Julian Strube bestimmt „Traditionalismus“ als einen „Oberbegriff für unterschiedliche Autoren, die die Überzeugung eint, dass im Innersten der verschiedenen Traditionen eine ursprüngliche Wahrheit erhalten geblieben ist“. Er untersucht seinerseits die besondere Wendung, die Julius Evola (1898-1974 u. Z.) dem Traditionalismus verlieh. Dieser war, wie zahllose seiner Publikationen belegen, selbst ein begeisterter Nietzscheaner. Strube behauptet, dass der so verstandene Traditionalismus „ein integraler Bestandteil der Neuen Rechten“ seit ihren Anfängen in den 1950er Jahren gewesen sei.22 Evolas berüchtigte politische Ansichten kulminierten etwa in seiner Selbstbezeichnung als „superfascista“23. Aktuelle kritische Forscher sprechen dementsprechend von einer politischen Positionierung Evolas, die „extremer als die offizielle Linie der [italienischen] Faschistischen Partei“ gewesen sei.24 Es wäre jedoch ein unzulässiger Kurzschluss, Winters Politik mit der von Evola gleichzusetzen, und es wäre kontrafaktisch, Winters Weltanschauung als Ablehnung der Moderne abzutun. Im direkten Widerspruch zu Evolas Antidemokratismus verweist Winter auf Forschungen von Sobolewska und anderen, um hervorzuheben, dass, wenn muslimische Einwanderer „die Staatsbürgerschaft erwerben, sie sie im Allgemeinen erstnehmen. Im Vereinigten Königreich erfüllen die [meist muslimischen] Bürger pakistanischer und bangladeschischer Herkunft mit größerer Wahrscheinlichkeit ihre Pflicht, wählen zu gehen, als ihre weißen Landsleute.“24 Ich packe meinen Rucksack für Glasgow und denke weiter über Winters rebellische und aufrichtig vertretene Prophezeiung über die Rolle, die der Islam für Europa und für die Zukunft der Welt spielen wird, nach, wie sie in Ismael und Hagar verkörpert wird.

III. Charity-Shops, Buchläden, Restaurants: Ismael im Albert Drive

Obwohl ich seit ungefähr einem Jahrzehnt zum ersten Mal wieder hier bin, hat Glasgow nichts von seiner Faszination für mich verloren. Es ist der rote Sandstein, aus dem die Stadt seit Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts erbaut wurde und der sich in schäbige Mietshäuser, stolze Herrenhäuser im Schottischen Baroniestil und alle möglichen Formen von behauenem Stein dazwischen einfügt, der mich nach Worten suchen lässt, die ich als biblisch bezeichnen möchte: „Habt ihr Augen und seht nicht?“26 Hätte das Schicksal andere Pläne für mich gehabt statt der Erziehung, die ich zwischen der Church of Scotland und den Episkopalen genossen habe, würde ich eine solche Sprache vielleicht als koranisch bezeichnen wollen. Nietzsche stellte sich in einem Brief an seine Schwester vom 11. Juni 1865 eine ähnliche Was-wäre-wenn-Frage:

Wenn wir von Jugend an geglaubt hätten, daß alles Seelenheil von einem Anderen als Jesus ist, ausfließe, etwa von Muhamed, ist es nicht sicher, daß wir derselben Segnungen theilhaftig geworden wären?27

Ich bin an einem besonders heißen Spätsommertag in Pollockshields unterwegs. Die katholische Kirche St. Albert‘s auf halber Strecke des Albert Drive erinnert an eine verblassende christliche Vergangenheit, aber es ist der heutige Islam, der hier ins Auge sticht. Islamic Relief und Ummah Welfare Trust sind zwei offensichtlich islamische Charity-Shops, an denen man vorbeikommt, wenn man vom Bahnhof Pollockshields East in die Gegend eintaucht. Ein Schild im Fenster des ersten Ladens verkündet: „Annahmestopp für Korane, islamische Texte oder Bilderrahmen in Spendenbeuteln.“ Wie gedruckte Bibeln in christlichen und postchristlichen Milieus kaum noch gefragt sind, steht auch der Islam vor der Herausforderung, eine textbasierte Religion in einem weitgehend post-alphabetisierten Zeitalter zu sein.

Während meinem Schaufensterbummel gehe ich in Gedanken weiter die Worte durch, mit denen ich hoffentlich mit den Bewohnern des Viertels ins Gespräch kommen werde. Wenn es darum geht, sie dazu zu bringen, offen über ihren Glauben und ihren Propheten zu sprechen, hilft es dann, Nietzsche zu erwähnen, eine Persönlichkeit, die für die meisten Menschen in diesen Straßen genauso viel bedeutet wie Leana Deeb für mich?28 Noch unentschlossen, welche Strategie ich wählen soll, sehe ich, dass Ummah Welfare in seinem Schaufenster eine altmodische gedruckte Einführung in den Islam für nur zweieinhalb Pfund anbietet. Ich gehe hinein und frage den Ladenbesitzer nach einem Exemplar. Obwohl uns ein anschließender Anruf beim Eigentümer mitteilt, dass diese Einführung nicht vorrätig ist, kommen wir zumindest ins Gespräch.

Atta Ali ist ein geselliger und gastfreundlicher Mann Anfang dreißig29, der mich sogleich hinaus auf den Bürgersteig führt, weil er spürt, dass ich mich dort beim Plaudern wohler fühle. Atta trägt einen vollen langen Bart und ist in einen Salwar Kamiz gekleidet, über dem er ein dickes, grünes Holzfällerhemd trägt, als würden ihn die – für diese Jahreszeit ungewöhnlichen – 26 Grad vor seinem Laden nicht stören. Er erzählt mir, dass er nur nach Pollockshields kommt, um ehrenamtlich zu arbeiten, aber eigentlich in East Renfrewshire, acht Meilen südlich, aufgewachsen sei. Dieses ist besser bekannt als ein jüdisches Viertel. Er scheint seine religiöse Toleranz signalisieren zu wollen, eine notwendige Vorsichtsmaßnahme vielleicht in einer Zeit, in der Vorwürfe des Antisemitismus gegen Europas Muslime unermüdlich sind. Als ich Winter erwähne, gibt Atta zu, dass er den „literarischen Mut“ des allgegenwärtigen Influencers Sam Harris bewundert, obwohl Harris sich im Internet einen Namen vor allem dadurch gemacht hat, dass er den Islam ernsthaft als das unerträgliche Andere darstellt.30

Atta fragt dann, ob Winter ein „Rückkehrer“ (revert) sei. Verwirrt antworte ich, dass Winter tatsächlich zum Islam konvertiert sei. Atta erklärt mir dann eine mittlerweile populäre theologische Sichtweise: Menschen, die als Kinder oder Erwachsene bewusst zum Islam konvertierten, kehrten lediglich zu dem Glauben zurück, den sie schon immer in sich getragen hätten. „Weißt du, wir waren einmal alle Moslems“, wie Atta es ausdrückt. Von dieser bizarren Behauptung überrascht, frage ich doch nicht weiter nach, obwohl ich natürlich neugierig bin. Wann soll das gewesen sein? Zu Lebzeiten des Propheten (ca. 570-632 u. Z.)? Oder gar schon bevor der Prophet inkarniert wurde?

Atta verbindet diese Tatsache mit dem pakistanischen Erbe der meisten Muslime in Pollockshields und erklärt, dass dieses Erbe überwiegend sunnitisch geprägt ist.31 Er ist nicht mit schiitischen Muslimen oder Muslimen anderer „Sekten“ befreundet, sagt aber, dass Schiiten in den örtlichen Moscheen zum Beten kämen, darunter auch in derjenigen, die hundert Meter weiter in einer Seitenstraße liege, und einfach nicht bekannt gäben, dass sie Schiiten seien. Nach dem Gebet zögen sie sich an und gingen leise, um Konflikte zu vermeiden. Attas Verwendung des Begriffs „Sekten“ macht mich auf etwas aufmerksam, das ich bei der Vorbereitung meiner Feldforschung hätte berücksichtigen sollen. Im Gegensatz zu der Art und Weise, wie Christen des 21. Jahrhunderts oft andere Kirchen und Konfessionen wahrnehmen, betrachten die meisten sunnitischen Muslime, ob in Glasgow oder weltweit, Schiiten, Sufis oder andere muslimische Minderheiten nicht als gleichberechtigte Glaubensgenossen, die Respekt verdienen, sondern als Ketzer. Heute können sie im Vereinigten Königreich zwar weitgehend in Frieden ihre alternativen Glaubenspraktiken und Theologien ausüben, aber sie werden in ökumenischen Debatten nicht als gleichberechtigte Partner angesehen.

Ein zu enger Fokus auf islaminternes Sektierertum jedoch würde die andere jüngere und von Fanatismus geprägte Geschichte Glasgows außer Acht lassen. Ich erinnere mich sofort an den antikatholischen Hass in der Stadt in den 1980er Jahren, als mein Bruder und ich noch Kinder waren, und der noch lange danach anhielt. Obwohl mein Bruder in Edinburgh lebte, bloß einen Steinwurf vom Epizentrum dieser Feindseligkeiten entfernt, war er dennoch Fan der Glasgow Rangers, einem Verein, der sein Weltbild auf protestantischem Isolationismus gründet, und bekam regelmäßig Tickets für dessen Heimspiele im Ibrox Stadium. Schon mit dreizehn Jahren war er kritisch genug, um die Lieder, die er dort hörte, nicht gut zu finden, aber natürlich beeindruckten sie ihn: rohe, emotionale Erscheinungen, eine Art besonders brutaler Wille zur Macht. Bis in die 1990er Jahre hinein hörten wir, wenn Robert mich mitnahm, wie Rangers-Fans provokante bis diffamierende Lieder über Bobby Sands sangen – das IRA-Mitglied, das 1981 im Alter von 27 Jahren nach einem 66-tägigen Hungerstreik im Gefängnis starb. Jim Slaven und Maureen McBride, zwei Mitglieder eines Teams von Soziologen, die sich mit Rassismus in Schottland befasst haben, lehnen sogar den „Begriff des ‚Sektierertums‘“ ab, um ein solches Verhalten zu verstehen, denn er

impliziert eine falsche Äquivalenz zwischen den Verhaltensweisen von Protestanten und Katholiken. Beide [Slaven und McBride] kommen darin überein, dass es hier in Wahrheit um Rassismus geht, der sich gegen Menschen von irisch-katholischer Abstammung richtet, und das dieser eine genuin schottische Entwicklung war und keine, die vom britischen Staat aufgezwungen worden wäre.32

Die Augustsonne ist zu stark, als dass ich mich mit dieser unrühmlichen Vergangenheit beschäftigen könnte. Zudem bekomme ich langsam Hunger. Das Café Reeshah in der 455 Shields Road hält sein Versprechen, „authentische asiatische Küche“ zu servieren – in diesem Fall authentische Küche aus Lahore, aus dem pakistanischen Teil des Punjab.33 Im Innenbereich schaffe ich es, den einen von zwei Tisch zu ergattern, der nicht in der Sonne steht; dort versuche ich, den riesigen Teller mit Gemüse-Pakora, der mir serviert wird und offiziell eine „Vorspeise“ ist, als Omen zu verstehen. Nietzsche war so sehr Chronist seiner eigenen Ernährung, insbesondere in Briefen und unveröffentlichten Notizen, dass unorthodoxe Gelehrte behaupten, seine implizite Ernährungsphilosophie könne bisher verborgene Bereiche seines Werks erschließen. Wenn man diese Fragmente erneut liest, tendieren sie eher Richtung Komik als Richtung universelle Magen-Gesetze, vor allem in Anbetracht des drängenden Bewusstseins, das Nietzsche dafür hatte, was ihn seine Café-Mahlzeiten kosteten. Als er im April 1881 aus Italien seiner Mutter und seiner Schwester in Deutschland Bericht erstattet, schwärmt der Essens-Guru:

Die Genueser Küche ist für mich gemacht. Werdet Ihr’s mir glauben, daß ich jetzt 5 Monate fast alle Tage Kaldaunen gegessen habe? Es ist von allem Fleische das Verdaulichste und Leichteste, und billiger; auch die Fischchen aller Art, aus den Volksküchen, thun mir gut. Aber gar kein Risotto, keine Makkaroni bis jetzt! So veränderlich ist es mit der Diät nach Ort und Klima!34

IV. Frittierte Fülle und Wortwörtlichkeit

Angesichts des Chana Masala, dem Kichererbsen-Curry, das in der Folge ebenso großzügig wie das Pakora serviert wird, möchte ich behaupten, dass die „Küche Glasgows“ wie für mich gemacht ist – mit ihrer frittierten Fülle und ihrem globalen Diaspora-Internationalismus. Später freue ich mich, zu entdecken, dass es etwas weiter südlich im Queen‘s Park einen Halal-Fish-and-Chips-Laden gibt. Was den Besitzer und die Mitarbeiter des Café Reeshah angeht, deutet nichts darauf hin, dass diese Männer in den Fünfzigern nicht auch Muslime sind. Aber sie kleiden sich westlich und zeigen keine Anzeichen dafür, dass sie sich an die wortgetreuen Grundsätze halten, denen Atta von Ummah Welfare die Treue schwört.

Ed Hussain kommt zu dem Schluss, dass wörtliche Auslegungen des Korans und der Hadithe35 heute die Lebensentscheidungen britischer Muslime dominieren – und dass das im Großbritannien des 21. Jahrhunderts am häufigsten zitierte Hadith-Kompendium möglicherweise das von Muhammad al-Bukhārī aus dem 9. Jahrhundert ist . Bärte wachsen von selbst, während wortgetreue Muslime auch von der Lehre des zweiten Kalifen, Omar (reg. 634–644 u. Z.), beeinflusst seien, dass Bärte nur einmal im Jahr getrimmt werden sollten.36 Gesichtsbehaarung an sich kann keinen Schaden anrichten, andere Formen des Literalismus hingegen schon. Al-Bukhārī überliefert ein Frage-Antwort-Gespräch zwischen dem Propheten und einer Gruppe ungenannter Gesprächspartner, in dem der Prophet berichtet, dass „die Mehrheit“ der Bewohner des ihm gezeigten „Höllenfeuers“ „undankbare Frauen“ seien. Von seinen Zuhörern zu weiteren Angaben über „widerborstige Weiber“ gedrängt, lässt al-Bukhārī sogar die Frauen unter seinen Zuhörern Mohammed zustimmen, dass „die Aussage einer Frau nur halb so viel zählt wie die eines Mannes“, wobei Mohammed erklärt, dass dies „aufgrund der Unzulänglichkeit des Verstandes einer Frau“ der Fall sei.37 Saqib Qureshi bezeichnet diese „grassierende Misogynie“ in seinem jüngsten muslimischen Beitrag Reclaiming the Faith from Orthodoxy and Islamophobia als ein Konzept, das „dem Koran völlig fremd“ sei.38 Mit solchen Argumenten verbündet sich Qureshi mit einer Minderheit von Intellektuellen am Oxford Institute for British Islam, die für „einen progressiven und pluralistischen muslimischen Glauben, der ausschließlich auf der Souveränität des Heiligen Koran basiert“, eintreten.39

Paigham Mustafa, ein Moslem aus Glasgow und Mitglied des Oxford Institute, musste fast ein Vierteljahrhundert lang extreme Gewaltandrohungen erdulden, weil er öffentlich diesen koranzentrierten Weg eingeschlagen hatte. Nachdem er Artikel veröffentlicht hatte, in denen er die Lehren der Moscheen in Frage stellte, erließ ein Ausschuss, der zwölf Moscheen in Glasgow vertrat, 2001 eine Fatwa gegen ihn. Das Dokument enthielt zwar keine explizite Todesdrohung, verglich Mustafa jedoch mit Salman Rushdie und stachelte damit zu schwerer Gewalt gegen ihn an.40 Mustafa, offensichtlich ein unorthodoxer Freigeist, der sich von der Drohung der Geistlichen nicht einschüchtern ließ, schrieb 2018 in einem auf Facebook veröffentlichten Brief über den Ramadan: „Entgegen der populären Praxis wird rituelles Fasten vom Koran nicht geboten.“41 Mögen Pakoras noch lange zu jeder möglichen Stunde genossen werden. Bevor ich das Café Reeshah verlasse, unterhalte ich mich mit seinem Chef, und wir finden eine gemeinsame Gesprächsgrundlage in den indischen und später pakistanischen Orten, in denen mein Urgroßvater und meine Großeltern jahrzehntelang gelebt und gearbeitet haben, und wo mein Vater geboren wurde: Lahore, Peshawar, Quetta. Was die Nachkommen der Kolonisierten und die Nachkommen der Kolonialisten verbindet und was sie trennt, ist ein und dasselbe.

Da ich mich mit islamischer Theologie bei Weitem nicht gut genug auskenne, um ihre Feinheiten eigenständig zu diskutieren, entscheide ich mich für einen journalistischen Ansatz und gebe meinem jeweiligen Interviewpartner den Raum, ohne Vorurteile zu sagen, was er wirklich denkt. In der Hoffnung, dass mir dies in der selbstbewusst „Islamic Academy of Scotland“ genannten Einrichtung am Maxwell Drive, nur wenige Minuten vom Café Reeshah entfernt, von Nutzen sein könnte, mache ich mich auf den Weg dorthin. Ich bewundere den kunstvollen viktorianischen Eingangsbogen des ehemaligen Pollockshields Bowling Club, aber als ich feststelle, dass die tristen Fertigbauten, in denen die Akademie untergebracht ist, geschlossen sind, kehre ich zum Madni Islamic Book Shop in der Maxwell Road zurück. Neben Brautkleidern und Lifestyle-Accessoires bietet der freundliche Ladenbesitzer dort Literatur in grellen Farben an, die mich an katholische Andachtshefte erinnert. Mir wird etwas mulmig. Ich entscheide mich für Understanding Islam von Maulana Khalid und Sayfulla Rahmani, das sich auf die islamischen Farben Grün und Weiß beschränkt. Als ich bezahlen will, legt der Verkäufer mir noch einen weiteren Brief Illustrated Guide kostenlos dazu. Auf dem Cover sind eine Million Muslime zu sehen, die sich nachts zum Gebet in der Masjid al-Haram, der großen Moschee von Mekka, versammelt haben – die Gläubigen leuchten in fluoreszierenden Farben. Am Sternenhimmel über ihnen strahlt ein fliegender Koran eine Milchstraße aus Licht aus, die unseren Globus umspannt, der sich, entgegen der Intuition, groß über den Menschenmassen und den Hochhäusern der Stadt dreht.

Auch meine beiden anderen Einkäufe vermitteln eine Botschaft, die sich deutlich von dem liberalen und unorthodoxen Islam unterscheidet, mit dem ich mich auf meine Reise vorbereitet habe. Mein Blick fällt auf The Need for Creed – Jinn: Beings of Fire. Diese populäre Dämonologie ist auf dickem Karton gedruckt und in überlangen Reimpaaren geschrieben, die nicht in Versfüße gegliedert sind. Illustriert mit kitschigen KI-Grafiken, verkündet es eine seltsame Theologie: „Dschinns sind sehr hochentwickelt und waren vor uns auf der Erde, doch sie bereiten Harm, / sie führen ein Parallelleben und hängen unterschiedlichen Religionen an – manche auch dem Islam“.42 Eher bedrohlich als nur seltsam ist der Titel Emergence of Dajjal: The Jewish King, eine schmale, groß gedruckte Abhandlung, in der Kapitelüberschriften wie „Die Auslöschung der Juden“ unmissverständlich machen, gegen wen sie sich richtet.43 Diese apokalyptische Literatur in Großdruck handelt von Imam Mahdi, einer Schlüsselfigur der Endzeit, von der jedoch die schiitischen und sunnitischen Muslimen ein völlig unterschiedliches Verständnis haben. Erst später erfahre ich, dass vergleichende Religionswissenschaftler Dajjal in einer groben Entsprechung zum Antichristen der christlichen Tradition sehen, und wundere mich erneut über die Zufälle, die mir meine Reise beschert hat. Ich schlüpfe in die Rolle eines Detektivs, um dieses Belegstück zu erhalten – am besten, ohne den Ladenbesitzer allzu direkt auf seinen Inhalt anzusprechen. Unaufgefordert erzählt er mir, als ich diesen Titel (für 3,50 Pfund) kaufe, dass sie als Kinder in der Elfenbeinküste oft Geschichten über Dajjal gehört hätten, dessen arabischer Name übersetzt „der Betrüger“ bedeutet.

V. Den Glauben bewahren, ungeachtet der Gewalt, die einem entgegengebracht wird

The Jewish King ist die Art antisemitischer Literatur, die sich überhaupt nicht darum bemüht, sich zu verklausulieren. Beiläufiger Antisemitismus unter den Muslimen in Glasgow und Großbritannien ist heute wahrscheinlich genauso verbreitet wie beiläufiger Antisemitismus unter den Christen Europas über Jahrhunderte hinweg bis zur zweiten Hälfte des letzten Jahrhunderts. Als ich am späten Nachmittag am St. Aloysius College, der Jesuitenschule im Zentrum von Glasgow, vorbeispaziere, kommt mir das Bild in den Sinn, dass die Muslime des 21. Jahrhunderts in Glasgow die Überlegenheit ihres Glaubens ebenso wenig in Frage stellen wie die Jesuitenpatres, die die Schule in den 1860er Jahren an ihrem heutigen Standort gründeten, diejenige des ihrigen. Wenn jedoch säkulare europäische Intellektuelle in den 2020er Jahren darauf bestehen, dass Antisemitismus für Muslime und in der islamischen Kultur tonangebend sei, verschließen sie bewusst mindestens ein Auge. Saqib Qureshi zeigt brillant, dass Muslime in der globalen Geschichte des Antisemitismus nur eine untergeordnete Rolle gespielt haben.

Während des gesamten Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit unterstützten Kirchenführer theologisch die antijüdische Politik, die mit Zwangsmassenbekehrungen, Vertreibungen, Morden und andere Gräueltaten durchgesetzt wurde. Von 1347 bis 1349 wurden Juden in ganz Europa verfolgt und verbrannt, nachdem sie beschuldigt worden waren, durch die Vergiftung von Brunnenwasser die Pest verursacht zu haben; viele Bekehrungen begleiteten diese tödlichen Szenen, sowohl „erzwungene als auch ‚freiwillige‘“44. Als sich die antijüdische Gewalt auch auf Spanien ausbreitete, wurden Ende des 14. und Anfang des 15. Jahrhunderts bis zu einem Drittel der Juden dieses Landes getötet und bis zur Hälfte zwangsweise konvertiert.45 Die genauen Zahlen sind umstritten, aber jüdische Augenzeugenberichte, wie der von Reuven Gerundi, der die Massaker von 1391 überlebte und angab, dass 140.000 Juden in deren Folge zwangsweise konvertiert wurden, müssen ernst genommen werden.46 Der Historiker David Nirenberg argumentiert, ohne notwendigerweise die Genauigkeit dieser Zahlen zu akzeptieren, dass die „massenhaften Konversionen“ von Juden auf der Iberischen Halbinsel in dieser Zeit in erster Linie Menschen betrafen, die „durch den Einsatz von [christlicher] Gewalt“ wurden, und dass diese Gewalt „die religiöse Demographie [der Region] verändert habe“.47

Qureshi stellt dieses blutige Erbe den „so gut wie nicht vorhandenen“ Zwangskonvertierungen gegenüber, die von Muslimen zur Zeit des Propheten und in dem Jahrhundert nach seinem Tod durchgeführt wurden. Qureshi behauptet, es gebe „keinen Beleg dafür, dass Mohammed irgendwen zur Konversion gezwungen habe“, und stützt sich dabei auf die Forschungsergebnisse von Asma Afsaruddin und Heather Keaney, um hinzuzufügen, dass bis zum Jahr 750 u. Z. „weniger als zehn Prozent der nichtarabischen Bevölkerung“, die vom entstehenden Islamischen Reich unterjocht worden war, zu der damals neuen Religion konvertiert war.48 Dieser Standpunkt wird von Sarah Stroumsa unterstützt, die „Zwangsbekehrungen“ im mittelalterlichen Islam als „nicht die Regel, sondern eine seltene Ausnahme“ bezeichnet.49 Wie Qureshi betont, ist es „amüsant und seltsam“, dass die allgemeine Meinung Zwangsbekehrungen in erster Linie mit dem Islam in Verbindung bringt, während es die christlich geprägte spanische Inquisition (1478–1834 u. Z.) war, die die größte gewaltsame Bekehrungskampagne in der Geschichte der Menschheit darstellt.50 Viele Belege deuten darauf hin, dass sowohl Juden als auch Muslime massiv unter dieser Gewalt gelitten haben. Trotzdem weigerten sich Zehntausende, wenn nicht Hunderttausende von Zwangskonvertierten, ihren alten Glauben aufzugeben, und praktizierten mit geschickten Ausflüchten weiterhin eine Art Krypto-Judentum und einen Krypto-Islam.51

Diese Geschichte enthält eine Allegorie, die lautstark Gehör verlangt. So sehr Populisten und Rechtsextreme auch antimuslimische Ressentiments schüren und ein Maß an Assimilation fordern, von dem sie selbst wissen, dass es nicht erreicht werden kann, reagieren die muslimischen Bevölkerungsgruppen in Pollockshields, Madrid oder Leipzig nicht damit, dass sie zum Säkularismus konvertieren oder ihre Koffer packen und wegziehen. Angesichts der vorsätzlichen Taubheit einiger politischer Führer muss wiederholt werden: Muslime betrachten Pollockshields und ähnliche Orte zu Recht als ihre Heimat. Im abschließenden Teil dieses Essays wenden wir uns Nietzsches überraschender Auseinandersetzung mit dem Islam und Pierre Klossowskis künstlerischen und muslimischen Reaktionen darauf zu. Jenseits der Lebendigkeit des roten Sandsteins und der von Möwen frequentierten Bürgersteige erinnert hier vieles daran, dass Heimat nicht zuletzt ein intellektueller, spiritueller und für manche ein Ort stolzer Religiosität ist, der nicht getrennt von rein physischen Gebieten existiert, sondern diese erweitert.

Alle Bilder sind Fotos des Autors. Das Titelbild zeigt das Schaufenster des Islamic Relief Shops im Albert Drive.

Bibliographie

Adamson, Peter: Philosophy in the Islamic World: A history of philosophy without any gaps, Volume 3, Oxford University Press: 2018.

Afsaruddin, Asma: The First Muslims: History and Memory. Oneworld, Kindle: 2013.

Almond, Ian: ‘Nietzsche’s Peace with Islam: My Enemy’s Enemy is my Friend’. In: German Life and Letters 56, no. 1 (2003), 43-55.

Ames, Christine: Christian Violence against Heretics, Jews and Muslims. In: M. S. Gordon, R. W. Kaeuper & H. Zurndorfer (Hg.): The Cambridge World History of Violence, II, 500–1500. Cambridge University Press: 2020.

Davidson, Neil & Satnam Virdee: Introduction. In: Understanding Racism in Scotland (hg. v. Davidson and Virdee). Luath: 2018.

Elshayyal, Khadijah: Scottish Muslims in numbers: Understanding Scotland’s Muslim population through the 2011 census. Alwaleed Centre for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World, University of Edinburgh: 2016.

Friedmann, Yohanan: Tolerance and Coercion in Islam: Interfaith Relations in the Muslim Tradition. Cambridge University Press: 2003.

Groff, Peter: Nietzsche and Islam [Besprechung von Nietzsche and Islam von Roy Jackson]. In: Philosophy East & West Volume 60, Number 3, July 2010.

Harvey, Leonard. P: Fatwas in Early Modern Spain. In: The Times Literary Supplement,

26.02.2006, Antwort auf Trevor J. Dadson: The Moors of La Mancha. In: The Times Literary Supplement, 10.02.2006.

Hopkin, Peter (Hg.): Scotland’s Muslims Society: Politics and Identity. Edinburgh University Press: 2017.

Husain, Ed: Among the Mosques: A Journey Around Muslim Britain. Bloomsbury: 2021.

Jackson, Roy: Nietzsche and Islam. Routledge: 2007.

Keaney, Heather N.: ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affan’: Legend or Liability? Oneworld Publications, Kindle: 2021.

Klossowski, Pierre: Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, übersetzt & eingeleitet von Daniel Smith, University of Chicago: 1997.

Klossowski, Pierre: Nietzsche und der Circulus vitiosus deus. Übers. v. Ronald Vouillé. Matthes & Seitz: 1986.

Klossowski, Pierre: Der Baphomet, übers. v. Gerhard Goebel. Rowohlt: 1987.

Netanyahu, Benzion: The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain. Random House: 1995.

Nirenberg, David: Mass conversion and genealogical mentalities: Jews and Christians in fifteenth-century Spain. In: Past & Present 174 (2002), S. 3-41.

Qasmi, Matloob Ahmed: Emergence of Dajjal: The Jewish King. Adam Publishers: 2013 f.

Qureshi, Saqib Iqbal: Being Muslim Today: Reclaiming the Faith from Orthodoxy and Islamophobia. Rowman & Littlefield: 2024.

Robbins, Michael: MENA Youth Lead Return to Religion. In: Arab Barometer, 23.03.2023, https://www.arabbarometer.org/2023/03/mena-youth-lead-return-to-religion/.

Ruby, Ryan: Brilliant Brother of Balthus. In: The New York Review, 08.08.2020, https://www.nybooks.com/online/2020/08/08/pierre-klossowski-brilliant-brother-of-balthus/.

Sobolewska, Maria, Stephen D. Fisher, Anthony F. Heath & David Sanders: Understanding the effects of religious attendance on political participation among ethnic minorities of different religions. In: European Journal of Political Research 54, Nr. 2 (2015), S. 271-287.

Staudenmaier, Peter: Evola’s Afterlives: Esotericism and Politics in the Posthumous

Reception of Julius Evola. In: Aries 25:2 (2025), S. 163-193.

Stroumsa, Sarah: Conversions and Permeability between Religious Communities. In: Schriften des Jüdischen Museums Berlin (2014), S. 32-39.

Strube, Julian: Esotericism, the New Right, and Academic Scholarship. In: Aries 25, 2 (2025), S. 304-353, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/15700593-02502006.

Swindon, Peter: ‘‘You will get your head chopped off” – Scots Muslim writer threatened by extremists. In: The Herald, 03.06.2018, https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/16266154.you-will-get-head-chopped-off---scots-muslim-writer-threatened-extremists/.

The Pew Research Centre: The future of the global Muslim population. Projections for 2010–2030. In: Population Space and Place, 13(1), (2011), S. 1-221.

Williams, Jacob: Islamic Traditionalists: “Against the Modern World?”. In: Muslim World 113, Nr.. 3 (2023), S. 333-354.

Winter, Timothy: Klossowski’s Reading of Nietzsche From an Islamic Viewpoint. 2025. [Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript, das Winter mit Henry Holland im Oktober 2025 teilte, mit einem Text, der Winters auf YouTube gehaltener Vorlesung ähnelt, aber leicht davon abweicht.]

Yılmaz, Feyzullah: Iqbal, Nietzsche, and Nihilism: Reconstruction of Sufi Cosmology and Revaluation of Sufi Values in Asrar-i-Khudî. In: Open Philosophy 6, (2003), S. 1-20, https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2022-0230.

Zaman, Moazzam: The Need for Creed — Jinn: Beings of Fire, Maktaba Dar-Us-Salam: o. J.

Fußnoten

1: Anm. d. Red.: Der zweite Bericht soll im Juni 2026 erscheinen.

2: Ian Almond, Nietzsche’s Peace with Islam, S. 43. Zitate aus englischen Texten wurden von der Redaktion ins Deutsche übersetzt.

3: Zu Iqbal und Nietzsche, s. Feyzullah Yılmaz, Iqbal, Nietzsche, and Nihilism. Zum hier diskutierten 1917er Artikel ad Nietzsche und Rumi s. ebd., S. 4 und 10-13.

4: Dieser unverblümte Neologismus soll meine eigene religiöse Position verdeutlichen: Ich bin zu sehr Atheist, um mich mit dem Titel „Agnostiker“ zu begnügen, bin aber dennoch unbeeindruckt von den Argumenten meines Verstandes für meinen Atheismus. Sie scheinen nur einer Version meines „Selbst“ zu dienen und nicht einer universellen Wahrheit. Daher der Begriff Agno-Atheist.

5: Kinder in Schottland beginnen die Primarschule zwischen viereinhalb und fünfeinhalb Jahren, abhängig von ihrem Geburtsdatum.

6: Vgl. Husain, Among the Mosques, Introduction.

7: Alba ist das gälische Wort für Schottland, s. Khadijah Elshayyal, Scottish Muslims in numbers, S. 8.

8: Dokumentiert in einer detaillierten Studie, die von Ed Husain als „unparteiisch“ beschrieben wird: The Pew Research Centre, The future of the global Muslim population, S. 15.

9: Vgl. Husain, Among the Mosques, Introduction.

10: Khadijah Elshayyal, Scottish Muslims in numbers, S. 8.

11: S. für mehr Informationen zu Pierre Klossowskis Biographie auch Ryan Ruby, Brilliant Brother of Balthus.

12: Aus Winters YouTube-Vorlesung, 40:16, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC8YJfyOkOY&t=356s.

13: Ebd., 2:46.

14: Aus dem Abriss von Klossowskis engagiertem Verhältnis zu Nietzsche, den Klossowskis Übersetzer Daniel Smith in seiner englischen Übersetzung von dessen Hauptwerk gibt (The Vicious Circle, S. viii).

15: „Die drei großen abrahamitischen Religionen“ kommen darin überein, dass Ismaels der Sohn von Abraham und Hagar ist. Es ist bemerkenswert, dass Hagar, der Torah zufolge, (zunächst) keine Jüdin ist. Sie ist eine „Konkubine“ bzw. Sexsklavin, die Abraham in Ägypten als Magd für seine kinderlose Frau Sarah erworben hatte und die ihm Sarah dann überreichte, damit er mit ihr einen Erben zeugt. Als sie jedoch selbst schwanger wurde, fing Sarah an, Hagar garstig zu behandeln und setzte durch, dass sie mit ihrem kleinen Sohn in die Wüste vertrieben wurde. Dort befahl ihr „der Engel Gottes“, in ihre ägyptische Heimat zurückzukehren, wo sie Ismael aufzog und er zum Stammvater der Araber wird. Diese Bibelstelle (Gen. 16, 1-16 & 21, 8-21) ist eine Basis für Winters Verständnis von Ismaels und Hagars als „Exilanten“. (Vgl. die Einträge zu Hagar und Ismael in der Encyclopaedia Britannica.)

16: Anm. d. Red.: Gemeint ist der Fifteenth Arab Youth Survey, der 2023 von der in Dubai ansässigen Unternehmsberatung ASDA’A BCW durchgeführt wurde (Link).

17: Michael Robbins, MENA Youth Lead Return to Religion.

18: Winter, Klossowski’s Reading, 3:11-5:21.

19: Jacob Williams, Islamic Traditionalists: “Against the Modern World?”, S. 335 f.

20: Ebd., S. 335.

21: Ebd., S. 333.

22: Julian Strube, Esotericism, the New Right, and Academic Scholarship, S. 305.

23: Zit. n. Williams, Islamic Traditionalists, S. 333.

24: Peter Staudenmaier, Evola’s Afterlives: Esotericism and Politics in the Posthumous Reception of Julius Evola, S. 170.

25: Sobolewskas Forschung, wie sie von Winter referiert wird, in einem unpublizierten Manuskript der bereits genannten Videovorlesung, welche Winter im Oktober 2025 freundlicherweise mit mir teilte. Der Text des Manuskripts unterscheidet sich geringfügig vom gesprochenen. S. Timothy Winter, Klossowski’s Reading of Nietzsche From an Islamic Viewpoint, S. 2; vgl. Maria Sobolewska, Stephen D. Fisher, Anthony F. Heath und David Sanders, Understanding the effects of religious attendance on political participation among ethnic minorities of different religions, S. 271-287.

26: Markus 8, 18.

27: Brief Nr. 1865, 469.

28: Deeb ist eine erfolgreiche junge muslimische Influencerin, deren YouTube-Kanal mehr als 1,5 Millionen Abonnenten zählt. Man betrachte etwa ihr Video darüber, „was bei der Oxford-Debatte wirklich passierte“ aus dem Juli 2025 (Link).

29: Ich habe diesen Namen und die Namen mehrerer anderer im Text erwähnter Personen geändert, um ihre Identität zu schützen.

30: In Videodebatten taucht Harris stets prominent auf, etwa mit Titeln wie „Wie man den Islam widerlegt“, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpWN1lOM1fE. Aber seine erfolgreichsten Kritiker, darunter Jonas Čeika, der bereits in POParts vorgestellt wurde (hier und dort), finden zumindest in ihren eigenen Kreisen mehr Gehör mit ihrer Kritik am Szientismus, den sie als Kernstück aller Polemiken von Harris betrachten. Vgl. A Critique of Sam Harris' ‘The Moral Landscape’.

31: Mehr schottische Muslime haben ihre Wurzeln in Pakistan als in irgendeinem anderen Land, s. Scotland’s Muslims Society: Politics and Identity, herausgegeben v. Peter Hopkin, 6 f.

32: Neil Davidson & Satnam Virdee, Introduction, S. 2.

33: Die philosophische Frage der Authentizität, insbesondere in Bezug auf Nietzsche, ist umstritten und komplex. Wir sind dankbar, dass Paul Stephan ihr eine ganze Doktorarbeit gewidmet hat.

34: Aus einer Postkarte an Franziska und Elisabeth Nietzsche, geschrieben am 6. April 1881 (Link).

35: Wörtlich übersetzt bedeutet Hadith „Bericht“ und bezieht sich auf die ursprünglich mündlich überlieferten Geschichten über Mohammed und seinen engsten Kreis, die ein oder zwei Jahrhunderte nach dem Tod des Propheten erstmals in separaten schriftlichen Sammlungen zusammengestellt wurden. Ed Husain erörtert den heutigen Einfluss der Hadithe von Mohammed al-Bukhārī (gestorben 870 u. Z.) in mehreren Abschnitten seines Buches Among the Mosques, darunter auch in Kapitel 1.

36: Ebd., Kapitel 5.

37: Muhammed al-Bukhārī, 52 Witnesses, Sunnah.com, abgerufen am 29. November 2022, http://sunnah.com/bukhari: 2658. Zit. n.: Saqib Iqbal Qureshi, Being Muslim Today, S. 100 f.

38: Ebd., S. 100 f.

39: OIBI website, https://oibi.org.uk/, Zugriff am 1. Oktober 2025.

40: Vgl. Peter Swindon, ”You will get your head chopped off” – Scots Muslim writer threatened by extremists.

41: Musatafa, zitiert nach ebd.

42: Moazzam Zaman, The Need for Creed — Jinn: Beings of Fire, ohne Nummerierung der Seiten.

43: Matloob Ahmed Qasmi, Emergence of Dajjal: The Jewish King, S. 66.

44: Vgl. Christine Ames, Christian Violence against Heretics, Jews and Muslims, S. 476 und 467, Fn. 17.

45: Vgl. Qureshi, Being Muslim Today, S. 214.

46: Vgl. Gerundi, zitiert in David Nirenberg, Mass conversion and genealogical mentalities: Jews and Christians in fifteenth-century Spain, S. 9.

47: Ebd., S. 10 & 3-41.

48: Vgl. Qureshi, Being Muslim Today, S. 216-219; Afsaruddin, The First Muslims: History and Memory, Kapitel „The Age of the Successors“, E-Book Abs. 13.3 und Heather N. Keaney, Uthman ibn ‘Affan: Legend or Liability?, Kapitel „Conquests“, E-Book Abs. 7.30.

49: Sarah Stroumsa, Conversions and Permeability between Religious Communities, S. 34. Dazu, wie sowohl sunnitische als auch schiitische Rechtsschulen Juden, Christen und einigen anderen religiösen Gruppen erlauben, ihre religiöse Identität zu bewahren, indem sie ihnen einen besonderen Schutzstatus gewähren, vgl. Yohanan Friedmann, Tolerance and Coercion in Islam: Interfaith Relations in the Muslim Tradition.

50: Vgl. Qureshi, Being Muslim Today, S 214 f.

51: Das Phänomen des Krypto-Judentums ist ein zentrales Thema in Benzion Netanyahus The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain, s. xvi-xviii. Zum Krypto-Islam s. L.P. Harvey, Fatwas in Early Modern Spain.