Nietzsche POParts

Aren’t words and notes

like rainbows and bridges

of semblance,

between that which is

eternally separated?

Nietzsche

POP

arts

Nietzsche

Sind

nicht

Worte

und

Töne

Regenbogen

POP

und

Scheinbrücken

zwischen

Ewig-

Geschiedenem

arts

Timely Blog on Nietzsche’s Insights

Articles

_________

“Peace with Islam?”

Wanderungen mit Nietzsche durch Glasgows muslimischen Süden: Teil 2

“Peace with Islam?”

Hiking with Nietzsche Through Glasgow’s Muslim Southside: Part II

In the second part of his article on hiking through Glasgow’s Muslim-esque Southside, our staff writer Henry Holland delves into Nietzsche’s impassioned yet scattergun engagement with the youngest Abrahamic religion. He investigates how the experimental novel The Baphomet by French artist and theoretician Pierre Klossowski – which got him hooked on the Islam-Nietzsche intersection in the first place – blends Islam-inspired mysticism, sexual transgression and Nietzscheanism itself into an inimitable potion. With insights on Muslim-esque readings of Nietzsche in tow, Holland returns with Fatima and Ishmael to Scotland’s largest city, thus wrapping up his travelogue whence it began.

I. Nietzsche’s Historical Islam?

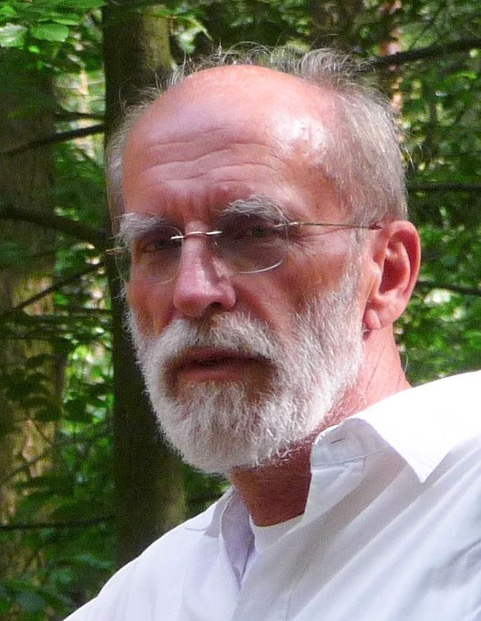

Our famously philosophizing rambler was mainly ignorant, creatively rather than stupefyingly so, of the historiographical argument voiced in Part One: the new religion spread in the first centuries following the Revelation to Mohammed primarily through speaking to new adherents, rather than coercing them. Instead, Nietzsche read Julius Wellhausen, historian of ancient religions, and provider of perhaps the most comprehensive histories of early Islam available in German in this period. Besides the author’s account of pre-Islamic culture in the Arabic world, published 1887, in which the author depicts Islam ‘as the culmination of the religious development of Arabic heathendom’, Nietzsche also devoured Wellhausen’s singular and furore-generating histories of ancient Judaism, prior to penning The Antichrist, which has also be translated as The Anti-Christian, in 1888.1 Wellhausen’s were only some of the flurry of ‘orientalist’ and Islam-focussed texts appearing in German, or in German translation, from the 1860s, which Nietzsche couldn’t get enough of. These included Gifford Palgrave’s Journeys Through Arabia, and several works by the era’s star orientalist, Max Müller. Nietzsche had read and excerpted Max Müller’s Essays on eastern religions in 1870-1871, finding confirmation that at least a ‘part of the Buddhist canon’ should be considered ‘nihilist’.2 Much points towards Müller’s writings on Indian philosophy as an entry point for Nietzsche’s later obsession with what he calls The Legal Code of Manu, and with what Indologists call the Manusmṛti — a metrical, Sanskrit text, written between 200 BCE-200 CE.3 From this base, Nietzsche’s immediate guide to the Code of Manu was what modern scholar Andreas Urs Sommer decrees a ‘highly dubious source’ in religious science terms, Louis Jacolliot’s 1876 book Les législateurs religieux. Manou. Moïse. Mahomet.4 Inspired by Jacolliot’s polemical juxtaposition of Manu with the Prophet, Nietzsche sought to bind Manu and Islam together, in a dense fragment from spring 1888, spaced carefully on the page but only published posthumously, which attempts a meta-philosophy of ‘Aryan’ and ‘Semitic’ religion:

What a yea-saying Aryan religion, spawned by the ruling classes, looks like:

Manu’s lawbook .

What a yea-saying Semitic religion, spawned by the ruling classes, looks like:

Muhammed’s lawbook. The Old Testament, in its older parts

What a nay-saying Semitic religion, spawned by the oppressed classes, looks like:

according to Indian-Aryan concepts: The New Testament — a Chandala religion

What a nay-saying Aryan religion, which has grown under the ruling estates, looks like

: Buddhism.5

Bizarrely, fantastically, some progressive Muslims are now turning to Nietzsche’s conception of Islam as a religion created by an exceptional (late ‘heathen’, Arabian, Medina-based) ruling class, which showed much metaphorical spunk. They view this as a pluralistic bastion against a singularizing, revivalist tendency among their co-religionists. The latter readily say ‘no — Islam was and is and can never be this way’; thus shutting down the conversation on how it could still serve as a life-affirming, modern religion. Nietzsche integrates his sketch linking Manu’s and Muhammed’s ‘law books’ into his best-known position on Islam, chapter 60 of The Anti-Christian. Ready for print by November 1888, the severe and permanent breakdown in Nietzsche’s mental health in January 1889 meant that the book didn’t appear until 1894, edited by his sister, and in a doctored form. Following the appearance of Colli and Montinari’s authoritative edition from the 1960s on, we can now be sure what Nietzsche wanted to say about the youngest major monotheism. Sounding like the rant a brilliant orator might deliver from Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, Nietzsche pounds Christianity with a barrage of heavy, insulting charges and praises Islam for how it manifested in ‘Moorish’ culture:

Christianity has conned us out of the harvest of the culture of antiquity and later it conned us out of the harvest of Islamic culture. The wonderful, Moorish culture world of Spain, fundamentally more familiar to us and speaking to our senses and taste more than Rome and Greece do, was trodden into the ground — I won’t say by what kind of feet — and why? Because it had noble instincts, men’s instincts to thank for its emergence, because it said yes to life, even through the rare and refined delicacies of Moorish life.

Condemning the Crusades that decimated this lifeworld, and the German nobility for their part in the Crusaders’ plundering, our orator suggests causes for this cultural degenerateness, and enjoins the reader to take sides in this culture clash:

Christianity, alcohol — the two large means of corruption … Per se, a choice shouldn’t even exist concerning Islam and Christianity, just as little as a choice should exist between an Arab and a Jew.6 The decision is given, no one is free to still choose something in this case. Either one is a Chandala or one is not … “War with Rome down to the knife! Peace, friendship with Islam!” — this is how that great free spirit Frederick II [1194-1259 CE], the genius amongst the German Kaisers, experienced and acted [in the situation] .7

Dividing all historical agents into either ‘Chandala’ or ‘the noble-minded [die Vornehmen]’ is a specifically 1888 move in Nietzsche’s philosophy. He appropriates the former term from Hinduism, where it means a member of the lowest caste (and specifically those who dispose of corpses), and makes it stand for ‘the lower [classes of the] people, the outcasts, and “sinners”’ the world over.8 Insisting that those who participated in Islam’s beginnings and enabled it to flourish are not Chandala is Nietzsche’s way of separating Islam categorically from latter-day, decadent Christianity. This taking-of-sides is picked up by Roy Jackson, author of seemingly the only full study on the subject in recent years, who maintains that ‘Islam can learn a good deal from Nietzsche’s critique of the “dead God” of Christianity’.9 By contending that Nietzsche doesn’t disown religious lives as such, but rather merely life-denying forms of the religious impulse, Jackson can set out the ‘two most fundamental options’ Islam is facing, either

to follow the same trajectory of Christianity in Europe and turning [sic.] its God into the ‘dead God’ that Nietzsche is so critical of, or to learn from Nietzsche’s religiosity and embrace a ‘living God’ that does not perceive secularisation as an enemy.10

Jackson’s intellectual manoeuvrings are hardly watertight. As Peter Groff reminds us, although Nietzsche’s modes and means of thinking are so radical that they go beyond atheism, this going beyond does not constitute a return to theism.11 But what matters here is not whether all the substrata of Jackson’s argument convince — they don’t; and Nietzsche’s own picture of a ‘yes-saying’ religion fits poorly to the religiosity on Pollockshields’ streets today — but rather the political and cultural battles, inter-Islam, that motivate Jackson to turn to Nietzsche in the first place. These are battles about the right way to re-encounter the religion’s ‘“key paradigms”: the Qur’an, the Prophet Muhammad, the city-state of Medina, and the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs [632-661 CE]’.12 For Jackson and his camp, this re-encounter must be ‘critical-historical’, so that believers can excavate honestly what Islam has been and could become, in semi-secular modernity. Groff and Jackson pit this approach against the way recent revivalist (Islamist) thinkers like Mawlana Mawdudi (1903-79 C.E.) have, transhistorically, refused to re-encounter these same paradigms, insisting instead that they are beyond critique, ‘pristine and all-encompassing’.13

Above all Jackson turns to Nietzsche in Beyond Good and Evil, not wanting to rid philosophical discourse of ‘the soul’ itself, but to redefine it as ‘mortal’, ‘as the multiplicity of the subject’, as a ‘societal construction of drives and affects’.14 This empowers Jackson to be multiple, and refusing of unilateralist accounts, in considering the souls who built the religious life and society of the ‘key paradigms’ period. Soon we arrive at a place utterly other to the mental maps most non-Muslims have of it: the first Islamic city-state was, on Jackson’s reading, ‘profoundly pluralistic’, recognised that ‘the secular and the religious’ should be separate realms, and was enlivened by the Prophet: less ‘a religio-political ruler (as assumed by contemporary revivalists), but rather a “charismatic arbiter of disputes”’.15

II. Souls and ‘Muslimness’ in Pierre Klossowski’s Maddening Art

Timothy Winter’s creating an Islamic take on Nietzsche builds on Pierre Klossowski’s reading of the same, and follows the trail of coded and yet decodable traces of Muslimness the French artist left behind him. These coagulate to a maximum density in The Baphomet, a 1965 novel that won the cachet-granting Prix des Critiques, but which has infuriated many readers and other critics since. The book is so weird that after lobbing it hard against a wall, its fascination may still exert itself, and have you picking up its scattered pages, and beginning reading it again. Not for nothing does Klossowski choose to locate the novel amongst a historical community that reactionary Catholic but also influential conspiracist voices have, over the centuries, recurringly suggested was Islamophile or even crypto-Islamic: the Knights Templar.16 The author throws such hints at the readers’ feet, then waits to see how they will react. Introducing Nietzsche as a character, and conflating him deliberately with the Islamophile Friedrich II is another bait Klossowski is setting up for us. The benefit of this book, and of Winter’s hermeneutic riff off it, is that spending time with these can shake up omnipresent rationalist prejudices against Islam. Klossowski’s aesthetics enact that which Islamic Studies scholar Thomas Bauer calls ‘constitutive of Sunnism’, namely ‘the process of making ambiguous’.17

Through the prologue, set in 1307 in a Knights Templar Order, immediately before the violent accusations of heresy and the crackdown on that organisation unleashed by King Philip IV of France, Klossowski just about maintains narrative tension. The plot’s far-fetched, but at least there is one. Valentine de Saint-Vit, Lady of Palençay, who has lost land by feudal order to the Templars, has been tipped off about King Philip’s plans, and decides to send her gorgeous fourteen-year old nephew, Ogier de Beauséant, into the Brothers at the Commandery. She hopes they’ll fall sexually for his charms so that she’ll get the evidence of ‘heresy’ she needs to discredit the ‘soldier-monks’ and thus get her land back. The sex, coats of mail and flagellation ‘games’ that ensue are no games for the graphically abused Ogier, whose inner voice we’re denied access to: our perspective on the action is that of the entitled and pederastic men. When this narrative culminates in the ritualistic killing of Ogier, who is stripped naked and hung, and left dangling from a rope, ‘in the void’ above the costumed knights, you’re left feeling that you’ve witnessed something that you shouldn’t have. It’s like reading a well-written report on a well-directed snuff movie.

That which Klossowski thinks justifies such a presentation only emerges slowly from the conversations between the ‘breaths’, or disembodied souls in Christian parlance, who debate one another in the novel’s main section. These breaths were, on death, ‘exhaled from the bodies that had contained them in life’, in the novel’s case from Ogier’s, and from many other bodies associated with the Templar Order, until the time when they will be ‘inhaled’ again, into new bodies, although not necessarily as new souls: with sometimes several entering a single human. Or will remain guarded for countless centuries, until ‘the Last Judgment and the Resurrection of the flesh’, which this theology states will allow them to rejoin their original bodies.18

Here we’ve left historical time, and indeed quotidian causality, and have entered what Winter, citing Louis Massignon (1883-1962 CE), might call ‘Islamic time […] a “milky way of instants”’.19 We could also term the dimension in which Klossowski locates the heart of the novel suprahistorical rather than transhistorical: it doesn’t deny linear, historical time, and the reality of what plays out there, but nor is it subordinate to this form of revelation. Klossowski choosing this cosmic time frame is providing a novelistic answer to Nietzsche’s take on the philosophy of souls. He articulates what he wants his book to enact in a letter to Jean Decottignies, subsequently reprinted as an appendix in the English edition of The Baphomet. Typically oblique, and in the tone of a guy who has important things to say but is refusing to say them, Klossowski nonetheless let’s slip clues about his theological preoccupations:

The Baphomet (gnosis or fable, or Oriental tale), should in no way be seen as a demonstration of the substratum of truth in the semblance of doctrine that is Nietzsche’s Eternal Return, nor as a fiction constructed on this personal experience of Nietzsche. On the other hand, my book purports to take into consideration the theological consequences thereof [i.e., of the Eternal Return] (i.e., a soul’s travels through different identities), as these coincide with the metempsychosis of Carpocrates [founder of a Gnostic sect, early 2nd century C.E.]20

Nietzsche establishment scholars today have mostly little truck with associations linking the Eternal Return with metempsychosis, or reincarnation as we would call it – if we talk about it at all. You do not, however, have to sign up to believing in reincarnation to question the over-determination, in the philosophy of souls, which still obsesses about the mortality question, and particularly about moments of death. Seen Islamically, these are no more than fleeting sparks, in a supernovic infinity of instants. If the soul is, qua Nietzsche, the subject’s multiplicity, i.e., if that subject is always a plurality and never a unity, why should the notion of a single soul in a single body make more rational sense than several souls inhabiting the same? If, as Nietzsche argues in Daybreak §109, none of us possess an impartial ‘intellect’ or sovereign soul, which can govern the conflicts we experience between our drives – if, on the contrary, this intellect is no more than ‘the blind tool of a different drive, a rival to that other drive, which is tormenting us with its vehemence’21 – then, and hypothesising that we could have chatted live to Nietzsche over tripe in the 1880s, why should we valorise the phantasm of the unified soul we would have then experienced over the plurality of his ideas, lyrically his souls, which have taken on multiple new lives since the cessation of his physical heart on 25 August 1900?

Klossowski gets his nose into this same material, but with more humour, by smuggling Nietzsche as a character into Baphomet. We encounter him in chapter VIII when we learn that he has incarnated ‘in the guise of an anteater’22 – yes, you heard – and under the name of Frederick the Antichrist, in the circle led by the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, Jacques de Molay (c.1240-1314 CE). Burnt at the stake in historical time after dozens of Templars had already been executed in the crushing of the order, the novel has ‘the Grand Master’ continuing to direct his knights in this in-between life, in what feels like an interminable waiting room. He has been tasked by the ‘Thrones and Dominions’, two orders or classes of angels, with guarding the souls of his murdered knights until the rightful Resurrection of the flesh at the Last Judgement; but pressures on Molay / the Master mean that his policing of this divine plan is hardly strict. One such pressure is this anteater. The Grand Master confuses the anteater Nietzsche with the aforementioned Friedrich II, and is not easily persuaded to give up his confusion: ‘What have I to do with Frederick? Hohenstaufen, no doubt? The Antichrist . . . an anteater?’23 Knowing that Friedrich II von Hohenstaufen had been decried by the papacy as ‘the anti-Christ’ for challenging its theocratic dominion was a further reason for Nietzsche selecting this title for the last work he wrote during his sane life. The German title, Der Antichrist translates just as relevantly as The Anti-Christian, and being anti everyday modern Christians is indeed the work’s core. Nietzsche also enjoyed the title’s ambiguity, allowing him to pose as the devil incarnate.

The devilish Nietzsche turns comical when we don’t just hear about him but first see him in Baphomet, ridden by none other than the murdered Ogier, who has disappeared for a long while, and astonishes with this stylish re-entry:

The group of guards disperse this crowd and form a barrier, while Ogier, mounted on a furry monster that he guides with a chain, slowly advances through the rows of tables; there is not a single guest that does not detain him at each step to examine as closely as possible the animal whose diminutive head and long muzzle obstinately sliding along the flagstones contrast with the enormous body and paws armed with long claws.24

Klossowski’s procession triggers several associations at once. It’s hard not to think of the tragi-comic photo of Nietzsche harnessed up beside Paul Rée, to pull the cart of the whip-wielding Lou Salomé. But it’s hard to also not think that this is a Dionysian inversion of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem mounted on a donkey: both scenes contain the deliberately ridiculous; both contain the ridiculed and the humiliated shedding their humiliation and their ridicule in acts of improbable overcoming. Beyond such obvious associations, we could consider Winter’s mode of interpretation: commensurate with Klossowski’s ‘ambiguous’ conversion to Islam, Winter suggests we can decode ‘Muslimness’, as opposed to Islam explicitly, ‘as a theme in his [Klossowski’s] later writings’.25 Reading the ‘furry monster’ scene this way, both Ogier, through what he has endured, and Nietzsche himself, in the form of the utterly othered anteater, are ‘the excluded’ who harbour a ‘just claim’. Again Winter returns to the polymathic and ecumenical Catholic Louis Massignon to describe Islam as the religion of that claim:

Islam is a great mystery of the divine will, the just claim [revendication] of the excluded, those exiled to the desert with their ancestor Ishmael, against the “privileged ones” of God, Jews and above all Christians who have abused the divine privileges of Grace.26

It’s possible to reject wholeheartedly Massignon and Winter’s claims about what Islam is, and to refute that Klossowski’s novel has anything to do with Muslimness, and yet still remain engrossed in the philosophical material that these debates are based on. Can Nietzsche’s unpublished note about ‘the eternal return of the same’ written in the Swiss Alps in August 1881, itself enduringly ambiguous and a catalyst for all of Klossowski’s responses to Nietzsche, really be dismissed as merely a no-nonsense ‘thought experiment’? No spiritual revelation, no epiphanic moment, nothing to see here, move along please, move along? Carefully laid out on the paper, headed ‘Draft.’, and annotated with the remark ‘6000 feet above sea level and much higher above all human things! –’, the note has certainly encouraged religiously-minded readers of Nietzsche to propagate their worldviews from within Nietzsche’s own work.27 According to Klossowski, the 1881 note is not a draft of an embryonic theory, but rather the description of a lived experience:28

The Return of the Same.

Draft.

- The incarnation of the foundational errors.

- The incarnation of the passions.

- The incarnation29 of knowledge and of the knowledge that destroys. (Passion of Cognizing)

- The innocent one. The individual as experiment. The relieving of life, humiliation, weakening – transition.

- The new heavyweight: the eternal return of the same. Infinite importance of our knowledge, errors, of our habits, ways of life for all that will come. What shall we do with the rest of our life – we, who have spent the greatest part of the same in the most essential ignorance? We shall teach the doctrine [die Lehre] – it is the strongest means of incarnating it within ourselves. Our kind of beatitude, as teacher of the greatest teaching.

Start of August 1881 in Sils-Maria30

III. Epilogue: Walking Pollockshields with Fatima and Ishmael

As I write this article I’m conducting an online interview with a woman in her late twenties who I’m friends with and who grew up in Pollockshields. Although she, like me, enjoys going hiking and trekking, neither of us have yet tramped the alpine paths around Sils-Maria, to follow in Nietzsche’s footsteps. Leaving behind thoughts about the Eternal Return speaking to a myriad of unfulfilled wishes, whether for pakora or for Swiss hikes, I find myself back on a video call. Again.

Fatima is an engineer working in aeronautics in the south of England, who defines herself primarily as Scottish and, as a secondary attribute, as Muslim. Nonetheless she agrees to talk to me about her faith. She speaks about her less religious dad, whose greater concern has been to work hard in routine jobs to ensure that his kids get the good school and university education they have now received. She describes her more religious mum, with whom she has talked more about questions of religious observance, like the hijab her mum had wanted her to wear when she was a teenager. When Fatima made it clear she didn’t want to, neither her mum nor any other family member insisted on this dress code. As if feeling a duty to educate me on the basics, Fatima foregrounds Islam’s ‘five pillars’, which she learnt about attending Muslim ‘Sunday school’: the profession of faith, prayer, charitable giving, fasting during Ramadan, and the once in a lifetime Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca. Fatima explains that she hasn’t been on the Hajj yet, but she has been on the `Umrah, or lesser pilgrimage.

Like many other believers I speak to, theological questions are not Fatima’s big thing. From the outside, her life looks entirely secular: working hard, traveling the globe, spending time with both female and male friends, and able to play bass guitar. In this last regard, she’s unimpressed by the entreaties of the hyper-literalists. Muhammad ibn Adam al-Kawthari is a pro-caliphate cleric based in Leicester, England, who propagates a ban on both playing and listening to instruments, but this is hardly the kind of voice that Fatima is listening to.31 Considering such ascetic and irrationalist manifestations in Britain’s Muslim community, and experiencing Fatima as their opposite, a level-headed person who affirms life’s diversity, I ask if she can imagine anything that would make her give up her religion altogether? Pausing for an instant, she labels her childhood religious education matter-of-factly as ‘indoctrination’, and talks about how people internalise the same – that it’s nothing you can just shrug off. She doesn’t forget how Glasgow Sunnis, the grouping she belongs to, ensure that those who formally renounce their faith get the ‘right’ message: ‘you will burn forever in hell’. I don’t press Fatima on this – adults recalling the existential religious images stamped on them as children need some of this to stay private. But I get the sense that she neither believes in hellfire nor refuses to disbelieve in it entirely. Religion is bound tight to family, culture, geographical community: the things that co-define you while you become who you are. With no alternative philosophical or religious worldview on the horizon with a substance and a pull comparable to that which Islam exerts, why would individuals like Fatima risk exiling themselves from it?

Back in Glasgow in the summer, and with time to kill before my evening interview with the imam at the Dawat-E-Islami mosque on Niddrie Road, I go and wait in Queen’s Park, just to the south of Pollockshields. Under soaring church spires, groups sit on the freshly-cut grass and gear up for the weekend, drinking and smoking joints as the heat recedes. A bare-footed Glaswegian of middle-Eastern heritage is even walking around with a tamed but untethered parrot on his shoulder. I’ve never seen such a display in public. If he or his ancestors ever belonged to a ‘nay-saying religion’ he’s now saying yes to life so vigorously that you sense it could end dangerously. The North Sudanese barbers’ who I’d popped into for a trim on the way to the park were also full of patter,32 their self-professed Muslimness no barrier to treating life as a convivial and slowly-evolving party. When I get into the mosque the mood changes. Courteously, the Pakistani imam, Shafqad Mahmood, his assistant Mansoor Awais, who interprets for him when the English gets more complex, and a further elder male congregant, Haji Ahmad, have found half-an-hour or so for me at short notice, before evening prayers begin. My uneasiness is down to what I’ve read about the Dawat-E-Islami organisation in Ed Husain’s liberal Muslim critique of the current state of his religion in the UK. Translating as ‘Invitation to Islam’, the Pakistan-based group first opened mosques in the UK around 1995 and now, as the imam tells me proudly, they have three centres in the greater Glasgow area, catering for over five hundred believers weekly.33 Husain for his part discusses the sectarian murder, in 2016, of Asad Shah, less than a mile from where we’re sitting and talking, by ‘a Dawat-e-Islami man’: albeit one from Bradford in the north of England, and not by a fellow Glaswegian.34 Shah’s ‘offence’, at least in his killer’s eyes, was to be an Ahmadi, a follower of the Indian Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908 CE) who claimed to be, concurrently, a ‘renewer of the faith’, ‘the promised messiah’, and ‘the mahdi (the rightly guided one who will appear at the end times together with the messiah)’: thus kickstarting a major new religious movement that is rejected uniformly by orthodox Muslims.35 As Husain had already interviewed a previous imam at the Queen’s Park mosque about Dawat-e-Islami and the 2016 murder, and had gotten evasive answers, I restrict myself to asking about the mosque’s attitudes to Shi’a, the Ahmadiya Muslim community, and other Muslim denominations. My overly orthodox question harvests a no-frills answer: ‘the Ahmadiya are not Muslims’. Surprisingly, Haji Ahmad adds that ‘we have Shi’a who come to pray here every week. Ahmadiya could even come and pray here if they wanted. If they didn’t say anything.’

Meant generously, the message is clear: mosque leaders tolerate non-standard beliefs only to the extent they remain utterly private. This strategy for ensuing conformity fits with what my question on the mosque’s attitude ‘to homosexual Muslims or to trans people?’ evinces: ‘We don’t accept them. But we wouldn’t say anything [if they came to pray at the mosque].’ I have to think of the story Fatima told me about a lesbian Muslim friend of hers trying to come out to her mother, and the friend’s mother being unable to embrace or support this reality. Hearing the story, you think the friend’s mother must have known long before about her daughter’s relationships – and tolerated them, as long as they remained hushed up.

No one is keeping quiet at the queer bookshop, Category is Books, just up the road from the Dawat-E-Islami mosque and religious school. Sadly I arrive outside opening hours, but the shop window is shouting out winning slogans to passers-by: ‘encourage lesbianism’, ‘better gay than grumpy’, ‘freedom of movement for all!’ and, in huge letters, the potentially game-changing ‘GET OFF THE INTERNET. DESTROY THE RIGHT WING.’ You’ll be forgiven for thinking that there is no dialogue between this shop’s community and that of the mosque. But the cause that has and will continue to generate dialogue arises when I ask the mosque’s leaders about the recipients of the organisation’s formal charitable status: ‘Over the last two years we’ve been funding aid deliveries via airplane into Gaza and the West Bank, food, water, and clothes, also looking after the orphans, no matter if the people there are Muslims, Christians or whatever.’ As the major British news platform The Canary reported recently, the group ‘No Pride in Genocide’ (Glasgow branch), ‘a broad coalition of LGBTQ+ Glaswegians’ demand of those running the city’s annual Pride march that they reject what Canary journalists call ‘companies directly profiting from Israel’s illegal occupation and ongoing genocide in Palestine.’36 If these concerns seem worlds removed from Nietzsche’s philosophical and Klossowski’s artistic hunches regarding Islam, we should turn to Judith Butler, surely the most widely-read philosopher of queerness of their generation, to see connections from them back to philosophy. Fighting back against Donald Trump’s Executive Order 14168 from January 2025, whose title makes its targets clear – ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government’ – Butler joins up the dots on the common cause that trans people, Muslims, and other people of migrant heritage can find and are finding, in today’s polarised societies. Moreover, they [Butler] hone in on that group of trans people most vilified by the far Right: ‘people assigned male at birth who seek to transition [to a female or other gender identity]’.37 They point out that ‘presumption[s]’ about such men held by an increased number in society are unevidenced, and that the great majority of such men transition because ‘they hope for a more livable life’. Topping this, Butler argues that there is no philosophical justification for taking the ‘few recorded instances’ in which men have transitioned to ‘seek entry into women’s spaces in order, it is presumed, to harm the women there’ as a general ‘model for transition’. Extrapolating from here, and writing in the ‘first-person we’, Butler concludes:

We do not point to the nefarious actions of particular Jews or Muslims and conclude that all Jews or Muslims act in that way. No, we refuse to generalise on that basis, and we suspect that those who do so generalise are using the particular examples to ratify and amplify a form of hatred they already feel.38

Was Nietzsche being nefarious and intending harm by calling Islam ‘a yea-saying Semitic religion, spawned by the ruling classes’, then cementing this prejudice in favour of Islam over both Christianity and Judaism in print? – ‘Either one is a Chandala or one isn’t.’ If so, the remedy for such damage could be found in his more circumspect, more moderate and more ambiguously artistic successors. Whether you’ll find such successors on the streets of Glasgow’s Southside or in great artists, and latter-day Muslims, like Pierre Klossowski, will depend on the kind of cultural or religious home you’re looking for.

All pictures are photographs taken by the author. The title image shows a stone-mason’s yard on the edge of Pollockshields, offering bilingual gravestones for the district’s Muslim residents.

Bibliography

Albany, HRH Prince Michael of and Walid Amine Salhab, The Knights Templar of the Middle East: The Hidden History of the Islamic Origins of Freemasonry. Weiser Books: 2006.

Almond, Ian: ‘Nietzsche’s Peace with Islam: My Enemy’s Enemy is my Friend’, German Life and Letters 56, no. 1 (2003), 43-55.

Balthus (Count Balthazar Klossowski de Rola Balthus): Balthus in his Own Words: A Conversation with Cristina Carrillo de Albornoz. Assouline: 2002.

Balzani, Marzia, Ahmadiyya Islam and the Muslim Diaspora: Living at the End of Days. Routledge: 2020.

Barber, Malcolm: The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge University Press: 1994.

Bauer, Thomas: A Culture of Ambiguity: An Alternative History of Islam. Translated by Hinrich Biesterfeldt and Tricia Tunstall. Columbia University Press: 2021.

Butler, Judith: ‘This is Wrong: Judith Butler on Executive Order 14168’, London Review of Books, 3 April 2025, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v47/n06/judith-butler/this-is-wrong, unnumbered.

Canary Journalists, The: ‘Glasgow Pride was just exposed as being complicit in Israel’s genocide’ in The Canary, 20 July 2025, unpaginated, https://www.thecanary.co/uk/news/2025/07/20/glasgow-pride-2025/.

Editors, various: Dictionaries of the Scots Language Online: 2025.

Groff, Peter: ‘Nietzsche and Islam’ [review of Nietzsche and Islam, by Roy Jackson], Philosophy East & West Volume 60, Number 3, July 2010, 430-437.

Husain, Ed: Among the Mosques: A Journey Around Muslim Britain. Bloomsbury: 2021.

Jackson, Roy: Nietzsche and Islam. Routledge: 2007.

Klossowski, Pierre: The Baphomet, translated by Sophie Hawkes and Stephen Sartarelli, with introductions by Juan Garcia Ponce and Michel Foucault. Eridanos Press: 1988.

Krokus, Christian: The Theology of Louis Massignon: Islam, Christ and the Church. Catholic University of America Press: 2017.

Newcomb, Tim (Translator and Editor of): Friedrich Nietzsche, Anti-Christian: The Curse of Christianity. Livraria Press: 2024.

Orsucci, Andrea. Orient-Okzident: Nietzsches Versuch einer Loslösung vom europäischen Weltbild. De Gruyter: 2011.

Smith Daniel: ‘Translator’s Preface’ in Pierre Klossowski, Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, translated by Daniel Smith. University of Chicago Press: 1997, vii-xiii.

Sommer, Andreas Urs Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, Ecce homo, Dionysos-Dithyramben, Nietzsche contra Wagner. De Gruyter: 2013.

Winter, Timothy: ‘Klossowski’s Reading of Nietzsche From an Islamic Viewpoint’, [Unpublished manuscript, shared by Winter with Henry Holland in October 2025, with a text similar but not identical to Winter’s lecture recorded for YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC8YJfyOkOY], (2025).

Footnotes

1: Wellhausen, Reste arabischen Heidentums (1887), cited from Andreas Urs Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, Ecce homo, Dionysos-Dithyramben, Nietzsche contra Wagner, 294-295. Sommer confirms Nietzsche was reading this work by Wellhausen in this period; see Sommer’s ‘Personenregister’, ibid., 920, for comprehensive references on Nietzsche’s reading of Wellhausen. Most translators continue to the follow the translation tradition established by Walter Kaufmann and others, and title their English works The Antichrist. Yet Tim Newcomb, author of one of the few translations to opt for The Anti-Christian as its title, is right to point out that Nietzsche’s primary target was Christians of his own age. Because ‘ein Christ’ translates as ‘a Christian’, deciding for the alternative title of The Anti-Christian is legitimate. Cf. Tim Newcomb, ‘Afterword’ in Friedrich Nietzsche, Anti-Christian: The Curse of Christianity.

2: Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, 110.

3: All references to Manu / the Law Book of Manu in Nietzsche’s work, and to the related concept of Chandala, date to 1888. A letter to Heinrich Köselitz on 31 May 1888 (link) suggests he has just discovered this work: ‘I thank these last weeks for an essential lesson: I found the Legal Code of Manu in a French translation [presumably Louis Jacolliot’s], which was made in India under the precise control of the highest-ranked priests and scholars. This [is an] absolutely Aryan product, a priestly codex of morality on the foundation of the Vedas, the notion of castes, and ancient ancestry’. (Emphasis in the original.) This and the other translations from Nietzsche’s writings in this essay are the author’s own. For more on orientalist texts read by Nietzsche, cf. Ian Almond, ‘Nietzsche's Peace with Islam’, 43; and indeed for sufficient context, the whole text of: Andrea Orsucci, Orient-Okzident: Nietzsches Versuch einer Loslösung vom europaischen Weltbild.

4: Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, 9 and 265.

5: Nachgelassene Fragmente 1888 14[95].

6: As Andreas Urs Sommer demonstrates, Nietzsche only inserted this cheap, anti-Semitic jibe into the final draft of this text: Sommer suggests this is Nietzsche playing to popular anti-Semitic sentiments among his potential readers. Cf. Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, 298.

7: The Anti-Christian, § 60. There has been much recent scholarship on Friedrich II’s fondness for and proximity to Islam. On Nietzsche’s sources for the same subject, see Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, 298-299, which also highlights the role played by August Müller’s writings on Friedrich II in Nietzsche’s reading. Müller recounts ‘as common knowledge […] how he [Friedrich II] took the most lively interest in the Arabs’ language and literature, pursued logic with his Muslim court philosophers, and even became half or even a whole heathen [i.e., a Muslim] himself, thus scandalising all pious people’. (Cited from Sommer, Kommentar zu Nietzsches Der Antichrist, 298.)

9: Summary of the position argued by Jackson as given by: Peter Groff, ‘Nietzsche and Islam’, 431.

10: Roy Jackson, Nietzsche and Islam, e-book-location: chapter 1, location 7.51.

11: Groff, 435. Groff considers The Joyous Science, §346 as one of Nietzsche’s clearest statements about ‘going beyond atheism’. Here Nietzsche writes: ‘If we wanted simply to name ourselves with an older expression like godless or unbelievers or even immoralists, we would still believe ourselves to be far from described by such epithets’.

12: Groff, 430.

13: Cf. ibid. 431; and Jackson, Nietzsche, chapter 2, 8.46-8.50.

14: Beyond Good and Evil, § 12.

15: Summary of Jackson’s argument given in Groff, ‘Nietzsche and Islam’, 432.

16: For a well-researched historical summary of such viewpoints, see Malcom Barber, The New Knighthood, 321. For an Islamophile account of the same history that is open to conspiracist thinking, see HRH Prince Michael of Albany and Walid Amine Salhab, The Knights Templar of the Middle East: The Hidden History of the Islamic Origins of Freemasonry, x-xi and 22-23.

17: Thomas Bauer, A Culture of Ambiguity: An Alternative History of Islam, 11, cited from Timothy Winter’s unpublished manuscript ‘Klossowski’s reading of Nietzsche from an Islamic viewpoint’, 1, which Winter generously shared with me in October 2025. I thank Winter heartily for his colleaguiality in sharing this book in progress with me at this stage. The text of Winter’s manuscript is mostly identical to his aforementioned YouTube lecture, but includes some minor changes.

18: Klossowski, The Baphomet, xv.

19: Winter, unpublished manuscript ‘Klossowski’s reading of Nietzsche from an Islamic viewpoint’, 8.

20: Pierre Klossowski, ‘Notes and Explanations’ in The Baphomet, 166-167.

21: Daybreak, § 109.

22: Italics my own. Klossowski, Baphomet, 111.

23: Ibid., 112.

24: Ibid., 125.

25: Winter, ‘Klossowski’s reading’, 10. Klossowski’s conversion is ambiguous in the sense that is recorded in a single, terse passage by his younger brother, Balthus: ‘My brother, Pierre, became a Dominican monk when he was young. Then, a lot later, he converted to Islam.’ Cited in: Balthus (Count Balthazar Klossowski de Rola Balthus), Balthus in his Own Words, 11. There is no reason to question Balthus’s account just because it’s terse: we could instead conclude that Klossowski’s Muslimness was a mostly private affair. Relevantly, this is not the only conversion in Klossowski’s life that Balthus describes: ‘[Adam-Maxwell Reweski] left my brother and me a sum of money that we could use for our education if we became Catholics. And we did convert to Catholicism, whereas my father was a Protestant.’ Ibid., 5.

26: Christian Krokus, The Theology of Louis Massignon, 175; cited in Winter, ‘Klossowski’s Reading of Nietzsche’, 11.

27: Nachgelassene Fragmente 1881 11[141].

28: See for example, the paper ‘entitled “Forgetting and Anamnesis in the Lived Experience of the Eternal Return of the Same”, which Klossowski presented at the famous Royaumont conference on Nietzsche in July 1964’, as described in Daniel Smith, ‘Translator’s Preface’, viii.

29: While the noun Einverleibung used in points 1 to 3 of this note could also be translated as ‘embodiment’ or even, more weakly and figuratively, as ‘incorporation’, disputing ‘incarnation’ as one valid translation makes no etymological sense. ‘Incarnation’ derives the from Late Latin incarnationem (nominative incarnatio), ‘act of being made flesh’ or entering into a body, while ‘embodiment’ in English also refers back primarily to the ‘embodiment of God in the person of Christ’, i.e., to the Old French incarnacion ‘the Incarnation’ (12th century C.E.). ‘Einverleibung’ in German carries strong Christian connotations, of which Nietzsche was evidently aware, just as ‘incarnation’ does in English.

30: Nachgelassene Fragmente 1881 11[141].

31: Al-Kawthari cited from Ed Husain, Among the Mosques, chapter 1.

32: Scottish English, patter: ‘A person’s line in conversation. This can mean ordinary chatting, as in “Sit doon an gie’s aw yer patter”; it can also mean talk intended to amuse or impress, as in “He’s got some patter that pal a yours”’. Cited from the Dictionaries of the Scots Language, https://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/sndns2837.

33: Dawat-e-Islami is estimated to own and run around forty properties in the UK as a whole.

34: For details of Shah’s murder and the theological role played by Dawat-e-Islami in it, see: Ed Husain, Among the Mosques, in the Glasgow section of chapter 8, ‘Edinburgh and Glasgow’.

35: Marzia Balzani, Ahmadiyya Islam and the Muslim Diaspora, 2.

36: The Canary Journalists, ‘Glasgow Pride was just exposed as being complicit in Israel’s genocide’ 20 July 2025, unpaginated.

37: Judith Butler, ‘This is Wrong: Judith Butler on Executive Order 14168’, unnumbered.

38:This and the previous citations taken from Butler, ibid., unnumbered.

“Peace with Islam?”

Hiking with Nietzsche Through Glasgow’s Muslim Southside: Part II

In the second part of his article on hiking through Glasgow’s Muslim-esque Southside, our staff writer Henry Holland delves into Nietzsche’s impassioned yet scattergun engagement with the youngest Abrahamic religion. He investigates how the experimental novel The Baphomet by French artist and theoretician Pierre Klossowski – which got him hooked on the Islam-Nietzsche intersection in the first place – blends Islam-inspired mysticism, sexual transgression and Nietzscheanism itself into an inimitable potion. With insights on Muslim-esque readings of Nietzsche in tow, Holland returns with Fatima and Ishmael to Scotland’s largest city, thus wrapping up his travelogue whence it began.

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche's Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche‘s Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Last week, Emma Schunack reported on this year's annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society on the topic Nietzsche's technologies (link). In addition, in his article this week, Paul Stephan explores how Nietzsche uses the machine as a metaphor. The findings of his philological deep drilling through Nietzsche's writings: While in his early writings he builds on Romantic machine criticism and describes the machine as a threat to humanity and authenticity, from 1875, initially in his letters, a surprising turn takes place. Even though Nietzsche still occasionally builds on the old opposition of man and machine, he now initially describes himself as a machine and finally even advocates a fusion up to the identification of subject and apparatus, thinks becoming oneself as becoming a machine. This is due to Nietzsche's gradual general departure from the humanist ideals of his early and middle creative period and the increasing “obscuration” of his thinking — not least the discovery of the idea of “eternal return.” A critique of the capitalist social machine becomes its radical affirmation — amor fati as amor machinae.

Nietzsche's cultural criticism is extremely ambivalent in its orientation towards modernity. Sometimes it seems as if he represents an almost modernist point of view, sometimes he tends towards the Romantic or even the reactionary. In order to visualize this ambiguity of Nietzsche's cultural criticism and his position on modernity, it is extremely instructive to look at his statements on the term “machine.” This allows, not least, a more nuanced view of his ethics of authenticity.

I. A Fighter against Machine Time

Statements in which he criticizes the machine and uses it as a metaphor for modern capitalism run like a common thread throughout Nietzsche's work from the earliest to the latest writings. He criticizes, for example, that the modern “external academic apparatus, [...] the educational machine of the university put into action.”1 Reduce scholars to mere machines like factory workers.2 Modern philosophers are “machines of thinking, writing and speaking”3. In a similar way to Karl Marx, Nietzsche even criticizes the subjugation of workers in this period, who are forced to “rent themselves out as physical machines.”4, himself under the machinery and blames them for their moral degeneration or for the sprouting of what he would later call “resentment”:

The machine terribly controls that everything is happening at the right time and in the right way. The worker obeys the blind despot; he is more than his slave. The machine Does not educate the will to self-control. It awakens a desire to react to despotism — debauchery, nonsense, intoxication. The machine evokes Saturnalia.5

Elsewhere, Nietzsche formulates the dialectic of machinization as follows:

Reaction against machine culture. — The machine, itself a product of the highest thinking power, sets in motion almost only the lower thoughtless forces of the people who operate it. In doing so, it unleashes an immense amount of power that would otherwise lie asleep, that is true; but it does not give the impetus to climb higher, to improve, to become an artist. She makes Acting and monoform, — in the long run, however, this creates a countereffect, a desperate boredom of the soul, which learns to thirst for varied idleness through it.6

Machinery thus serves as an educator of inauthenticity, producing flexible machine people who are unable to educate themselves:

The wild animals should learn to look away from themselves and try to live in others (or God), forgetting themselves as much as possible! They feel better that way! Our moral tendency is still that of wild animals! They should become tools of large machines besides them and would rather turn the wheel than be with themselves. Morality has been a challenge so far Not to deal with yourselfby shifting your mind and stealing time, time and energy. Working yourself down, tiring yourself, wearing the yoke under the concept of duty or fear of hell — great slave labor was morality: with the fear of the ego.7

Even in his late work, Nietzsche considered submission to the “tremendous machinery”8 of the “so-called 'civilization'” (ibid.) — its main features: “the reduction, the ability to pain, the restlessness, the haste, the hustle and bustle” (ibid.) — as the main reason for “the The rise of pessimism“(ibid.). He speaks disparagingly of the arbitrarily fungible “small [n] machines”9 of modern scholars and ridicules the fact that it is the task of the modern “higher education system”10 Be, “[a] us to make a machine for man” (ibid.), a dutiful “state official” (ibid.) as a, supposed, complete manifestation of Kant's ethics. When viewed honestly

That wasteful and disastrous period of the Renaissance turns out to be the last large time, and we, we modernity with our fearful self-care and charity, with our virtues of work, unpretentiousness, legality, scientificity — collecting, economic, machinal — as a faint Time [.]11

And last but not least, he speaks in Ecce homo about the “treatment I receive from my mother and sister”12 as a “perfect [r] hell machine” (ibid.).

The estate of the early 1870s even states programmatically:

handicraft learning, the necessary return of the person in need of education to the smallest circle, which he idealizes as much as possible. Combating the abstract production of machines and factories. To create ridicule and hate against what is now considered “education”: by opposing more mature education.13

The modern utilitarian machine world is Nietzsche in its totality a horror, which he critically confronts with the Dionysian culture of antiquity:

Antiquity is in its entirety the age of talent for Festfreude. The thousand reasons to rejoice were not discovered without acumen and great thought; a good part of the brain activity, which is now focused on the invention of machines, on solving scientific problems, was aimed at increasing sources of joy: the feeling, the effect should be turned into something pleasant, we change the causes of suffering, we are prophylactic [precautionary; PS], that palliative [“wrapping in the sense of palliative care; PS].14

In the machine world, people surround themselves with anonymous goods instead of real things, through which they could enter into a resonating relationship with their originators:

How does the machine humble. — The machine is impersonal, it deprives the piece of work of its pride, its individual Good and faulty, which sticks to all non-machine work — that is, its bit of humanity. In the past, everything buying from artisans was a Marking people, with whose badge you surrounded yourself: the household and clothing thus became a symbol of mutual appreciation and personal belonging, while now we only seem to live in the midst of anonymous and impersonal sclaventhum. — You don't have to buy the ease of work.15

In contrast to personally manufactured, authentic, artisanal products, the mechanical goods did not impress with their intrinsic quality, as could only be determined by experts, but only through their effect and thus deceive the general public.16

However, Nietzsche summarizes this comprehensive critique of modern commodity production and the world of life bewitched by it most harshly in Human, all-too-human together:

Thought of Discontent. — People are like coal mines in the forest. Only when young people have burned out and are charred, like them, will they usefully. As long as they steam and smoke, they may be more interesting, but useless and even too often uncomfortable. — Humanity mercilessly uses each individual as material to heat its large machines: but why use the machines when all individuals (i.e. humanity) only use them to maintain them? Machines that are their own purpose — is that the umana commedia [human comedy; PS]?17

The proximity of these ideas to a Rousseauist, romantic critique of capitalism, but also to Marx, is remarkable and obvious. For Nietzsche, the “machine” becomes the epitome of what Marxism describes as the “fetishism of commodity production” and he comes surprisingly close to a clear understanding of the rederizing mechanisms of the capitalist mode of production here. — Of course, this metaphor is not astonishing in view of the fact that the valorization of “authentic production” over craft into the “absolute metaphors” (Hans Blumenberg) of modern thinking of authenticity On whose tracks Nietzsche moves completely at these points. The living and the dead, the machine and real practice, are juxtaposed in a harsh dualistic way.18

In view of these clear words, it is significant that, in parallel, there was an almost diametral revaluation of the machine in Nietzsche's writings from around 1875.

II. Man as a Machine

Remarkably, this first takes place in Nietzsche's letters. Between 1875 and 1888, he repeatedly referred to his own body or even himself as a “machine” in them and reported on their good or poor functioning.19 In this sense, he already speaks in the Morgenröthe in a purely descriptive sense of the body in general as a machine20 and is also moving on to calling humanity as such in a neutral way.21 Here he apparently draws on the naturalistic wing of the Enlightenment, such as Julien Offray de La Mettries L'homme machine (Man as a machine, 1748), as part of his generally growing interest in naturalistic explanations of human behavior in that period.

Already in Human, all-too-human Nietzsche admiringly compares Greek culture with a speeding machine whose tremendous speed made it susceptible to the slightest disturbances.22 In the estate of the 1880s, Nietzsche then just as uncritically designed a “depiction of the machine 'man'”23 and moves on to seeing something good in the machinization of humanity:

The need to prove that to an ever more economic consumption of people and humanity, to an ever more closely intertwined “machinery” of interests and services A countermovement belongs. I refer to the same as Elimination of humanity's luxury surplus: It should bring to light a stronger species, a higher type, which has different conditions of origin and conservation than the average human being. My term, my allegory For this type, [...] is the word “superman.”

That first path [...] results in adaptation, flattening out, higher Chineseness, instinct modesty, satisfaction in reducing people — a kind of stoppage in Human level. Once we have the unavoidably imminent overall economic administration of the earth, then humanity can find its best meaning as machinery at its service: as a tremendous train of ever smaller, ever finer “adapted” wheels; as an ever increasing superfluence of all dominant and commanding elements; as a whole of tremendous power whose individual factors Minimal powers, minimal values represent. In contrast to this reduction and adaptation of the M <enschen>to a more specialized utility, the reverse movement is required — the generation of synthetic, of buzzing, ofthe justifying People for whom this machinalization of humanity is a precondition of existence, as a base on which he can his Higher form of being Can invent yourself...

He just as much needs the antagonism the crowd, the “leveled”, the sense of distance compared to them; he likes them, he lives from them. This higher form of aristocratism is that of the future. — Morally speaking, that overall machinery, the solidarity of all wheels, represents a maximum in the Exploitation of humans represents: but it presupposes those for whose reason this exploitation sense has. Otherwise, it would in fact simply be the overall reduction Werth-Reduction of the type human, — a decline phenomenon in the biggest style.

[...] [W] As I fight, is he economic Optimism: as if with the growing expenses Aller The benefits of all should also necessarily grow. The opposite seems to me to be the case: Everyone's expenses add up to a total loss: the human being becomes lesser: — so that you no longer know what this tremendous process was for in the first place. One for what? one new “What for! “— that is what humanity needs...24

In line with the idea of a — hoped-for — transformation of levelling into a new aristocracy, which has also been repeatedly discussed in the published work25 Although Nietzsche now adheres to his earlier critique of maschization, he also hopes that she will at the same time give birth to a new class of “supermen,” who will dominate the “army” of the machine of completely subjugated slaves. In antichrist He clearly states this political 'utopia' and explains it naturalistically: “That you are a public benefit, a wheel, a function, there is also a determination of nature: not the society, the species luck, which the vast majority are only capable of, turn them into intelligent machines.”26.

Is there already in Human, all-too-human aphorisms in which submission to the machine is described not apologetically, but also not critically, but purely descriptively as a “pedagogy,”27 Is he now increasingly going about recommending this subordination, even in the case of scholars, as a healing method against resentment28 and sees the early scene of the civilizational formation of humanity in the machinization of large parts of humanity by a small “caste” of brutal “predator people.”29

III. The Genius as an Apparatus?

But Nietzsche's fascination for machines does not stop there. Although he speaks himself in the Happy science against understanding the entirety of being as a machine, but not because this would mean devaluation or reification, on the contrary: “Let us beware of believing that the universe is a machine; it is certainly not based on a goal, we honor it far too much with the word 'machine'”30. Nietzsche, on the other hand, describes the human intellect completely uncritically as a machine in the same book31 And in the same way, human soul life as a whole should now be understood as a machine32. This applies, of all things, to the “genius”, which has been glorified since early work as the epitome of the highest authentic selfhood, which Nietzsche used from Morgenröthe compare with a machine over and over again.33 He speaks in the Götzen-Dämmerung, with none other than Julius Caesar as an example, even of “that subtle machine working under extreme pressure that is called genius.”34 and in a late estate fragment of him as the “most sublime machine [s] that exists”35.

The modern “rape of nature with the help of machines and the so harmless technical and engineering ingenuity”36 now celebrates Nietzsche as “power and sense of power [...] [,] hubris and godlessness” (ibid.) and therefore as an antithesis to modern decadence.37 An estate fragment from 1887 even states:

The task is to <zu>make people as usable as possible and to get them closer to the infallible machine as far as possible: for this purpose, he must work with Machine virtues be equipped (— he must learn to perceive the states in which he works in a machine-usable manner as the most valuable: it is necessary that the others be stripped as far as possible, as dangerous and disgusted as possible...)

Here is the first stumbling block boredom, the uniformity, which involves all mechanical activities. This Learning to endure and not just endure, learning to see boredom played around by a higher stimulus [.] [...] Such an existence requires philosophical justification and transfiguration more than any other: the pleasant Emotions must be discounted as lower rank by some infallible authority at all; the “duty itself,” perhaps even the pathos of reverence in regard to everything that is unpleasant — and this requirement as speaking beyond all usefulness, deliriousness, expediency, imperativity... The machinal form of existence as the highest most venerable form of existence, worshipping oneself.38

The revaluation is thus finally complete: It is no longer just a matter of creating a slave status of “machine people” with a sense of “advancement” of the species, which is confronted by a small group of “authentic” leaders, but all people should act equally as cogs of a large overall machine whose process is affirmed as an end in itself. In fact, only a distinction can be made between people who are cogs and those who form self-contained machines and are therefore destined to rule. Self-development as machinization.

Nietzsche thus becomes a pioneer of cybernetic techno-fascism, as Ernst Jünger had already foreseen on the eve of the “seizure of power” as a possible alternative to liberal humanism39 and today in “avant-garde fascist” circles40 again In vogue is, but also the post-modernist transfiguration of “becoming a machine” as a supposed subversive practice, as promoted tirelessly by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. The utopia of the flexible person as a “cyborg”41. It is almost funny that both the critical and the affirmative use of the machine metaphor apply equally in Nietzsche's last writings and testifies to the conflict of his thinking and his subjective indecision.

If you combine this last turn in Nietzsche's thinking with the concept of “eternal return,” which finds its tangible counterpart in the endless circle of machinery,42 Even though Nietzsche himself does not attempt this parallel, this analysis reveals the deeper reason for Nietzsche's “waste”: The growing insight into the structural dynamics of modern societies made him (ver) doubt more and more the possibility of realizing their authenticity. Not least because — as his letters mentioned above testify, which are probably not by chance at the very beginning of his “return” from machine striker to admirer — he recognized that the machinization of the world is not just an external skill, but an internal event from which one is subjectively unable to escape. Authenticity could then only be realized as a continuous fight against oneself. Dissatisfied with this, Nietzsche is now striving to radically affirm the machinization of the world mythologized as the “eternal return.” An affirmation which, however, like the talk of “hell machine” in Ecce homo underlines that it could only be successful at the price of complete self-abandonment, since its essence — as early Nietzsche recognized so clearly — is a misanthropic process which forces people to affirm something that, other than delusional, cannot be affirmed.

The obvious way out would be precisely to take on this fight against internal and external machinization — both in the sense of individual heroism and in the sense of political “machine-storming” — and to endure the internal conflict that the modern world of life imposes on people. But this is precisely where Nietzsche fails; he — contrary to what he himself called for — cannot maintain this tension, must “bridge” the “arc” of his ethics of authenticity43 with the help of his mythological constructions, which became ever more grotesque, ever more out of touch with reality in his late work. The real challenge that the ideal of authenticity poses to individuals is therefore to maintain one's own authenticity in a society dominated by inauthenticity without going crazy or succumbing to the conformist temptation of flexibility.

Literature

Benjamin, Walter: One way street. Frankfurt am Main 1955.

Ders. : Central Park. In: illuminations. Selected fonts. Frankfurt am Main 1977, pp. 230—250.

Haraway, Donna: A Cyborg Manifesto. In: Socialist Review 80 (1985), PP. 65—108.

Younger, Ernst: The worker. Domination and Form. Stuttgart 2022.

Stephen, Paul: Modernity as a culture of violence. Nietzsche as a critic of violence. In: Engagée. political-philosophical interventions 4 (2016), P. 20-23.

Footnotes

1: About the future of our educational institutions, Lecture V.

2: See, for example, ibid. and ibid., Speech I.

3: The benefits and disadvantages of history for life, paragraph 5. See also Schopenhauer as an educator, paragraph 3.

4: Subsequent fragments No. 1880 2 [62].

5: Subsequent fragments No. 1879 40 [4].

6: Human, all-too-human Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, Aph 220.

7: Subsequent fragments No. 1880 6 [104].

8: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 9 [162].

9: Beyond good and evil, Aph 6.

10: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, Aph 29.

11: Ibid., Aph 37.

12: Ecce homo, Why I'm so wise, paragraph 3.

13: Subsequent fragments No. 1873 29 [195].

14: Subsequent fragments No. 1876 23 [148].

15: Human, all-too-human Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, Aph 220.

16: Cf. Ibid., aph. 280.

17: Human, all-too-human, Vol. I, Aph. 585.

18: In this phase, Nietzsche even decisively expresses understanding for the workers' displeasure and recommends to them his ethics of authenticity as a way out of the dilemma “either a slave of the state or the slave of an overthrow party becomes must“(Morgenröthe, Aph 206). During this time, such mind games brought him remarkably close to anarchism (see e.g. Morgenröthe, Aph 179).

19: Cf. Bf. to Carl von Gersdorff v. 8/5/1875, No. 443; Bf. to dens. v. 26.6.1875, No. 457; Bf. to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche v. 30.5.1879, No. 849; Bf. to Heinrich Köselitz v. 14/8/1881, No. 136; Bf. to Franz Overbeck v. 31/12/1882, No. 366; Bf. to Malwida von Meysenbug v. 1/2/1883, No. 371; Bf. to Heinrich Köselitz v. 19/11/1886, No. 776; Bf. to Franziska Nietzsche v. 5.3.1888, No. 1003 and Bf. to Franz Overbeck v. 4/7/1888, No. 1056. It turns out that Nietzsche does not write these letters to “anyone,” but to his most intimate “small circle.” Nietzsche wrote to Overbeck on 14/11/1886: “The antinomy My current situation and form of existence now lies in the fact that everything that I as philosophus radicalis Nöthig Have — freedom from work, wife, child, society, fatherland, faith, etc., etc. I as many deprivations I feel that I am happily a living being and not just an analytical machine and an objectifying device” (No 775). A letter to Heinrich Romundt dated 15/4/1876 is also remarkable, which states: “I never know where I am actually more ill once I am ill, whether as a machine or as a machinist” (No 521).

20: Cf. Aph 86.

21: Cf. Subsequent fragments No. 1876 21 [11].

22: Cf. Human, all-too-human Vol. I, Aph 261.

23: Subsequent fragments No. 1884 25 [136].

24: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 10 [17].

25: See e.g. Beyond good and evil, Aph 242.

26: Paragraph 57.

27: Cf. Vol. I, Aph. 593 and Vol. II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, 218.

28: Cf. Subsequent fragments 1881 11 [31] and On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 18.

29: Cf. ibid., para. II, 17.

30: Aph 109.

31: Cf. Aph 6 and Paragraph 327.

32: Cf. Subsequent fragments No. 1885 2 [113] and The Antichrist, paragraph 14.

33: Cf. Morgenröthe, Aph 538; Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, Aph 8 and The Wagner Case, paragraph 5.

34: rambles, Aph 31.

35: Subsequent fragments No. 1888 14 [133].

36: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 9.

37: This passage is one of the most ambiguous in Nietzsche's work. At first glance, it makes sense to regard them as a critique of modern science and technology (see also my own essay on this subject Modernity as a Culture of Violence). But the late Nietzsche does not use “power” and even “rape” in any critical sense at all, as he keeps in the genealogy Clearly stated elsewhere:”[A] n yourself Of course, injuring, raping, exploiting, destroying cannot be anything “wrong”, insofar as life essential, namely hurtful, raping, exploitative, destructive in its basic functions and cannot be thought of at all without this character” (para. II, 11). And in the passage itself, it says: “[S] elbst still measured with the measures of the ancient Greeks, our entire modern being, insofar as it is not weakness but power and sense of power, looks like pure hubris and godlessness.” If one assumes that Nietzsche still refers positively to the “ancient Greeks” and their ethics of “measure,” this sentence should be read critically — but it is also obvious to understand it as meaning that in the described aspects of modernity, Nietzsche sees just the opposite of the “masterly moral” features of modernity that oppose their general nihilism. What objection should the declared “Antichrist” have against “ungodliness”?

38: Subsequent fragments No. 1887 10 [11].

39: Cf. The worker.

40: Just think of the corresponding visions of billionaires Elon Musk and Peter Thiel.

41: See, for example, Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto.

42: Walter Benjamin already recognized this connection between “eternal return” and the cyclicity of the capitalist economy (cf. One way street, P. 63 & Central Park, PP. 241—246).

43: Cf. Beyond good and evil, Preface.

Fascinated by the Machine

Nietzsche‘s Reevaluation of the Machine Metaphor in His Late Work

Last week, Emma Schunack reported on this year's annual meeting of the Nietzsche Society on the topic Nietzsche's technologies (link). In addition, in his article this week, Paul Stephan explores how Nietzsche uses the machine as a metaphor. The findings of his philological deep drilling through Nietzsche's writings: While in his early writings he builds on Romantic machine criticism and describes the machine as a threat to humanity and authenticity, from 1875, initially in his letters, a surprising turn takes place. Even though Nietzsche still occasionally builds on the old opposition of man and machine, he now initially describes himself as a machine and finally even advocates a fusion up to the identification of subject and apparatus, thinks becoming oneself as becoming a machine. This is due to Nietzsche's gradual general departure from the humanist ideals of his early and middle creative period and the increasing “obscuration” of his thinking — not least the discovery of the idea of “eternal return.” A critique of the capitalist social machine becomes its radical affirmation — amor fati as amor machinae.

Nietzsche and Cyborgs

The International Nietzsche Congress 2025

Nietzsche and Cyborgs

The International Nietzsche Congress 2025

Under the topic Nietzsche's technologies international visitors were once again invited to the Nietzsche Society conference in Naumburg an der Saale this year. In the period from October 16 to 19, in addition to various lectures, a film screening and a concert, there was also an art exhibition to visit. Our author Emma Schunack was there and reports on her impressions. Her question: How can Nietzsche's technologies find expression in the technological age?

Editorial note: The conference report does not mention the important “Lectio Nietzscheana Naumburgensis,” with which Werner Stegmaier rounded off the conference on Sunday morning and took up the topic of the conference again in a completely different way by asking about Nietzsche's own “philosophizing techniques.” We have now published this important talk in full length with the kind permission of the author (link).

Friedrich Nietzsche himself spent many years of his childhood and youth in the city on the Saale. His family home still stands today in the vineyard 18. In 2008, the Friedrich Nietzsche Foundation Naumburg was founded here, which operates the Nietzsche Documentation Center as a publicly accessible research and cultural center, which once again serves as the venue for the Nietzsche Congress this year.

If you get to the Congress from the train station, you first come across the former Nietzsche family home. A winding house surrounded by wine, the ground floor of which is now a small bookshop with a selection of Nietzsche's writings. If you go just a few steps further, the Documentation Center is located right next to the historic Nietzsche House as a modern new building with bright walls and large window fronts. Inside the building, there are light-filled rooms on three floors, which provide space for a library, an archive, two exhibition areas and two plenary rooms. There are Nietzsche busts in the corridors, and large lettering with quotes from the philosopher is repeatedly affixed to walls and stairs.

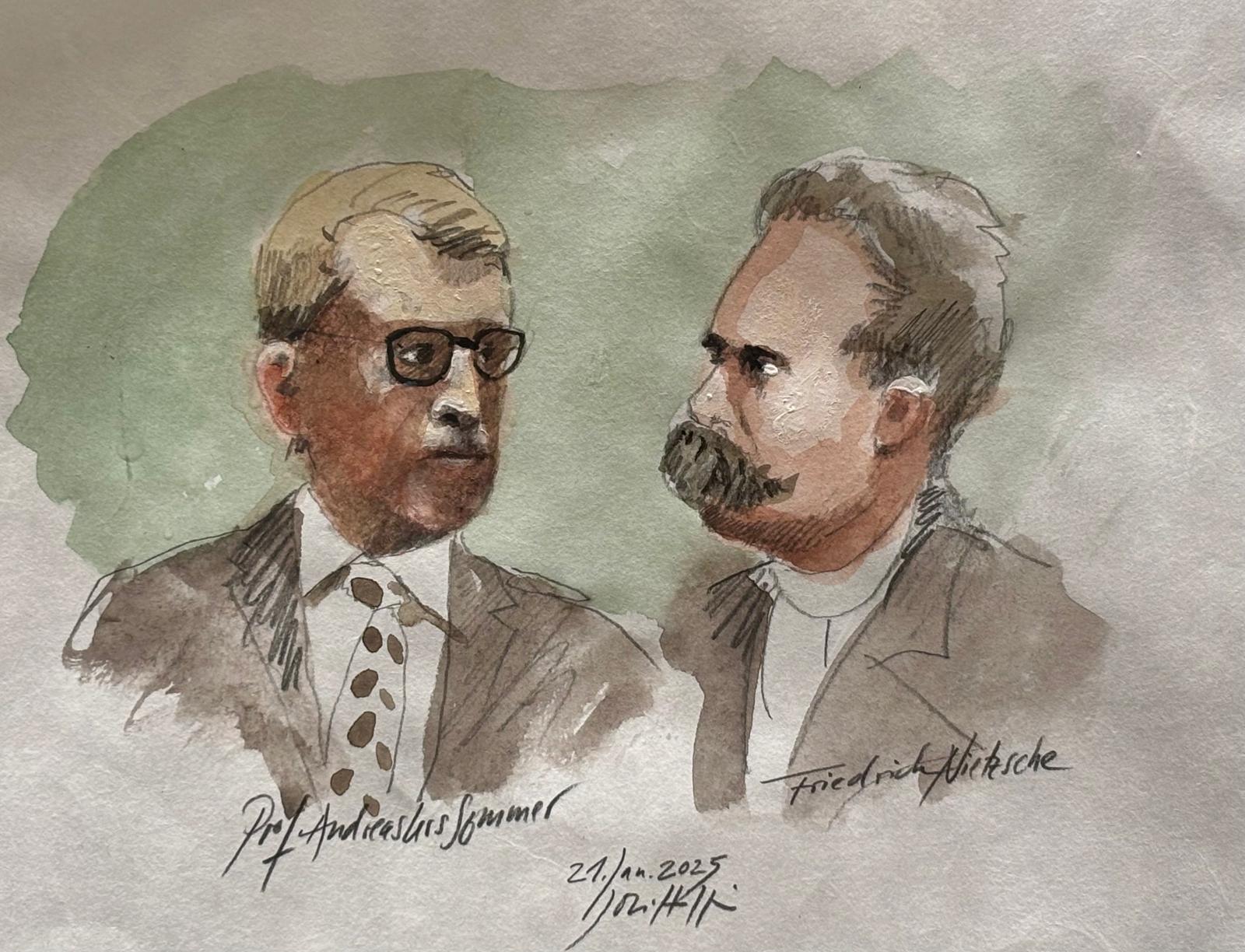

The conference, chaired by Edgar Landgraf, Catarina Caetano da Rosa and Johann Szews, starts on Thursday afternoon with various greetings, including from the Director of the Friedrich Nietzsche Foundation, Andreas Urs Sommer, and the Chairman of the Nietzsche Society e.V., Marco Brusotti. The talks given this weekend on Nietzsche's technologies are divided into various sections, from “Cultural and Body Techniques”, “Nineteenth-Century Techniques” and “Anthropo and Media Techniques” to “Techniques of Discipline and Subjectification” to “Linguistic and Rhetorical Techniques.” In this way, the term technology is broadly defined and provides a basis for various interpretations.

I. Human Thinking as a Technique

What mental techniques must humans practice in order to think like Nietzsche? Emanuel Seitz, research assistant at the University of Basel, will address this question and its implications in his presentation Nietzsche, a stoic of intoxication. The techniques of a mental exercise. Seitz is primarily concerned with the questions: What do I have to do to become Nietzsche? Can Nietzsche be described as a Stoic? To answer this question, Seitz first explains three techniques for the Stoa's spiritual reflection: the practice of thinking, desire and drive. It should be possible to learn those exercises or techniques. They aim to form an appropriate idea of the true value of things through reflection. With the help of the exercises, humans should reach value judgments that are not just subjective, they should practice distance and look down from the universe like God. Practicing these techniques of thinking creates a kind of cosmic consciousness, as the Stoa teaches, which leads to a new form of freedom of judgment. It is only by practicing these exercises that people are able to reevaluate existing values.

Seitz combines these Stoa exercises with Nietzsche's own practice The technique of philosophy as an art of living, It is about action, not knowledge, According to Seitz. He argues that although Nietzsche comes to completely different results than the Stoa, not to a humanist ideal of compassion, but to self-discipline and selfishness as a passion. Although Nietzsche despises moralism, he deals with questions about The will for cosmic justice. Seitz therefore argues that Nietzsche could very well be described as a Stoic in terms of the method of his thinking, in complete contrast to the content of his philosophy. In conclusion, he therefore expressly pleads for Nietzsche to be taken seriously as a technician of thought.

II. Post-humanist Perspectives on Nietzsche

In line with this year's theme of the congress, some of the lectures relate to post-humanist epistemology and Science and Technology Studies. Babeth Nora Roger-Vasselin places particular focus on post-humanist positions, who in her presentation Incorporation out of business. Incorporation seen as a technique Nietzsche's concept of incorporation attempts to combine with the figure of a cyborg after Donna Haraway.

Roger-Vasselin regards Nietzsche's concept of incorporation as a technique of individuation. This is what incorporation describes as an organism actively simulates its sensory experience, a formative process that all living beings share. Roger-Vasselin describes this process of incorporation as technique, since it is not natural or innate to us, it is instead the result of education based on individuation. With this technique These are standardized processes through forms and rhythms.

But what could that technique of incorporation look like in the technological age? Roger-Vasselin argues in this context using the figure of the cyborg and refers to Donna Haraway. The cyborg is described by Haraway as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a product of both social reality and imagination.”1, a creature that is neither natural nor artificial, but both at the same time and nothing alone2. For Haraway, cybernetic organisms are neither nature nor culture, but have always been natural culture3. Conceptually, with the figure of the cyborg, Haraway blurs supposed boundaries between humans, animals and machines and establishes a way of thinking of difference beyond dualisms4: “To be one is always to become together with many”5. And so Roger-Vasselin argues that community forms in the technological age should be collectives of cyborgs.

Matthäus Leidenfrost presents another post-humanist perspective on Nietzsche in his presentation Animal husbandry and human taming. Nietzsche on anthropotechnical practices, In which he deals with the relationship between animals, humans and technology in Nietzsche. He discusses how Nietzsche himself described humans as a sick animal that has been tamed with the tools of culture and hides behind clothing and morals. According to Nietzsche, humans living in the flock are deficient and deprived of their own investments. In this way, people themselves suffer from life. At this point, Leidenfrost is referring to Peter Sloterdijk, who, in this context, formulates an invitation to people to recognize their own animality and to become part of an open bio-cultural existence. Illness is not a rigid state here, it is decay, but also recognition and a new beginning, an opportunity for growth. Leidenfrost continues to refer to current trans- and post-humanist discourses and he too refers to Donna Haraway at this point. He reads Nietzsche's reflections in this regard as an invitation to humans to open themselves up in an affective dimension in the age of perfection and within their own domestication of their own animality, in the spirit of the end of So Zarathustra spoke: “He denied and brewed all their virtues from the wildest, bravest animals; only then did he become — a human being. ”6

III. Aesthetic Experience