Nietzsche POParts

Aren’t words and notes

like rainbows and bridges

of semblance,

between that which is

eternally separated?

Nietzsche

POP

arts

Nietzsche

Sind

nicht

Worte

und

Töne

Regenbogen

POP

und

Scheinbrücken

zwischen

Ewig-

Geschiedenem

arts

Timely Blog on Nietzsche’s Insights

Articles

_________

Thus Spoke the Machine

Imitating Nietzsche with AI

Thus Spoke the Machine

Imitating Nietzsche with AI

The continuous refinement of large language models, or LLMs for short, allows increasingly accurate stylistic interpretations of texts. This also applies to the writing styles of philosophers. For example, it has recently been possible to chat with Socrates or Schopenhauer — usually with consistent quality and limited depth of content.1 In recent months, our guest author Tobias Brücker has tried to generate exciting Nietzsche texts using various AI methods. In the following, he will present some of these generated, “new Nietzsche texts”, describe their creation and draw a brief conclusion.

I. Writing with LLMs

As part of my private writing project, I intend to use various AI language models (LLMs) to generate targeted philosophical texts that are inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche in terms of style and content. I'm not just interested in philosophically sounding texts with a few Nietzsche buzzwords, as is currently happening with simple prompts on ChatGPT. My goal is to obtain differentiated texts that are based on specific phases of work or types of texts (e.g. maxims, aphorisms or letters) in literary, content and contextual terms. To this end, I train AI models specifically with Nietzsche texts in order to capture stylistic and rhetorical peculiarities more precisely.

The following texts were generated using the ChatGPT-4O model using “Instruction Tuning”. This means that I have achieved more and more the desired result with selected examples and many prompts. This is often sufficient to generate individual and short text examples, while for systematic generation, a model is trained with larger, processed amounts of data through “fine-tuning”.2 For laymen, the technical set-up of locally trained models is still associated with time-consuming imponderables and depends on powerful hardware. In general, it is advisable to carry out tests that are as manageable as possible in order to be able to understand the results and optimize them accordingly in a controlled manner.3

II. Nietzsche-Aphorisms about Sorrento and Sicily

One obvious type of curiosity when imitating is to ask yourself what someone might have thought or said about something. I have often worked with landscape aphorisms because they can be formulated more openly and do not necessarily have to follow a concise thesis. In this way, I tried to generate an aphorism for the Italian city of Sorrento. I have searched three books that are close together in time for suitable passages on landscapes and hiking: the first volume of Human, All Too Human (April 14, 1878), Assorted Opinions and Maxims (March 12, 1879) and The Wanderer and His Shadow (December 18, 1879). The results were bumpy at first. I suppose because Sorrento is a specific city and therefore the description had to fit this concretion. The titles were also aphoristically ineffective. In addition, ChatGPT's talkativeness got in the way, which is why I intervened briefly a few times to reach the following result:

Surrentum ex umbra. — The South in retreat, a corner where even the light takes a break: cool, shady, yet quietly demanding. The rocks are almost weightless, leaning on — tired perhaps, or wise. Everything seems half said here. The wind whispers of the past and silent grottoes dream of sirens that have long since fallen silent. Here, where every thought is beguiled by limes and oranges, aromatic scents. Here where only the colors are clear — thinking fables.

This result had to be optimized. I did like the basic mix of topics — southern Sorrento, the shady trees, the rocks... The contrast of clear sensual colors and beguiling spiritual thinking even gave the text some aphoristic punch line. However, the orientation was based on the aphorism “Et in Arcadia ego” from Wanderer and his shadow (link) too strong: Too often, the pattern “Here, where...” is used. In addition, the metaphor of the leaning rocks for Sorrento seemed inconclusive to me. Through suggested abbreviations and densifications as well as by searching for a title, I came to the following result:

Fugit lux, Surrentum apparet. — The South is retreating from itself. Here, where even the light stops — cool, shady, yet challenging. The rocks are half-high, straight and almost weightless: not falling, not defiant — but grown old, tired and clever. Everything is half-loud here, half said. The wind whispers about the past. The caves dream of the sirens echoing. And in between: penetrating scents of lemon, salt, sun.

I really liked the stilimitation here, although the meaning of the content became leaner, especially in the final sentence — especially since a single aphorism must be coherent compared to a series of aphorisms. The two examples are therefore only intended to illustrate what an LLM can achieve through imitation and how this can be promoted with prompts, objectives and suitable materials.

In another series of experiments, I asked ChatGPT to generate an aphorism about Sicily. Nietzsche did not write one of these either in Messina or anywhere else — and yet it seemed almost like a gap to me that there is no such thing in Nietzsche's works. The following aphorism has thus been generated over several stages of revision. For the “Instruction Training”, I also used examples of other Nietzsche locations, letters from Messina and a few excerpts from historical travel guides from Nietzsche's library:

Sicily. — On Sicily's soil, two powers are fighting for the wanderer's soul: there Mount Etna, a symbol of Dionysian fire, everlasting and destroying passion — here the temples, heralds of Apollinan clarity, beauty and harmony carved in stone. Only those who have the courage to purify themselves in fire are able to climb the heights of pure knowledge and thus be truly human in harmony with the divine. Many burn themselves up during this venture, dying down in the excess of emotion — but who wanted to talk them out of their affirmation, which derived their right from existence?

It can be seen here that GPT-4o can work very well with pairs of terms: Apollonian powers, temples, recognition vs. Dionysian fire, volcano, feeling. However, the phases of work are mixed here, as the Nietzsche of 1878/79 no longer argues so strongly with Dionysian and Apollinian. Since there were no quotations from early Nietzsche in my instructional examples, it is clear that ChatGPT added some elements from Nietzsche's philosophy. This shows that LLMs tend to produce a generic or blending work phases, which they calculate based on their training data. This weakens the result from the point of view of a plausible imitation of the work. The final sentence, in which a new punchline should lie, was also always difficult. This was achieved reasonably well only after a few attempts.

III. Two Generated Nietzsche-Maxims from the Middle Phase

I consistently got better results when I settled on short forms and a style: be it letters, aphorisms, or maxims. With a selection of maxims from Assorted Opinions and Maxims (AO) I then had GPT-4o generate a new spell. Usually two or three so that I could choose one for further use. I liked the following two maxims:

Humans are nature that is ashamed — and culture that apologizes itself.

Between drive and virtue flickers man.

The titles of the maxims were once again difficult to generate with the same prompt. With a few inquiries and sample texts, I think it was then easy to deliver or correct them. In the following example, the first title “Windbreak” was replaced by “Individual”, which looks concise and appropriate:

Individually. — Some things fall not because they are weak, but because they are free.4

This maxim is thought-provoking, makes sense and can be read extensively several times. In particular, the ambiguous “free standing” (standing unprotected, being alone, being free, etc.) invites different interpretations. The maxim is compatible with the game of separation (“individual”) and freedom (“free standing”), which has its price (e.g. free spirits in Human, All Too Human), and also a perfect fit for the Middle Nietzsche context.

Another procedure was to have the LLM combine original passages from AO into a new maxim. Due to the original material and the ambiguity of the original maxims, astonishingly good results can be generated here. I found this very successful:

Silent duty. — Anyone who works in the shadow of the big doesn't know the brilliance, but the weight.

IV. Conclusion and Outlook

My conclusion is: With suitable sample material and instructions, LLMs can aptly imitate Nietzsche's style in individual short texts. As complexity and volume of text increase, it quickly becomes more difficult to generate meaningful texts — for example, a series of 10 related aphorisms. The connection of work phases, styles, and contemporary contexts to Nietzsche's work significantly increases plausibility and makes the results more interesting. However, the coherence of work phases in particular is difficult to achieve due to the already trained, generic Nietzsche styles of prefabricated LLMs. This speaks for LLMs own finetunings. My technical skills and time options have so far been limited here: The Nietzsche generators trained by me through fine-tuning have so far proven to be poor compared to “instruction tuning” with leading models such as ChatGPT or Claude. However, these time-consuming fine-tuning sessions have helped me to understand better and better understand exactly what an LLM does and how I can guide it through prompts. In addition, you get to know philosophical works from a different perspective when you have them processed through an LLM — this learning effect should not be underestimated, especially for people who have previously dealt exclusively with qualitative and interpretive processes. As fine-tuning is becoming increasingly easier and more accessible, I expect a lot of potential here in the medium term.

At this stage of the technical development of LLMs, I am interested on the one hand in exploring the possibilities and on the other hand in the attitude of (human) readers, who always read and interpret through the lens of their author's ideas. I have therefore deliberately not yet addressed the opportunities and risks for Nietzsche scientific research. It is only possible to record for the moment: LLMs open up numerous opportunities to experiment with philosophical texts. Such experiments may seem pointless to some because they are not “original” quotations or because they do not consider calculated texts to be philosophically relevant. These reactions show how our ideas of authorship, originality, or human origin shape the philosophical idea of authorship. These formations move in the flow of time. With regard to pseudo-Aristotelian writings, pseudepigraphy or the anonymously published texts of the Enlightenment, I would not rule out that the close view of philosophical authorship and historical-critically edited “complete works” will change.

Tobias Brücker has a doctorate in cultural studies and is head of HR personnel development at the Zurich University of the Arts. He has researched Nietzsche's working methods and published in 2019 the monograph On the road to philosophy. Friedrich Nietzsche writes “The Wanderer and His Shadow” ("Auf dem Weg zur Philosophie. Friedrich Nietzsche schreibt 'Der Wanderer und sein Schatten'"). He is interested in all facets of diets, authorship, and creativity techniques in philosophy and the arts.

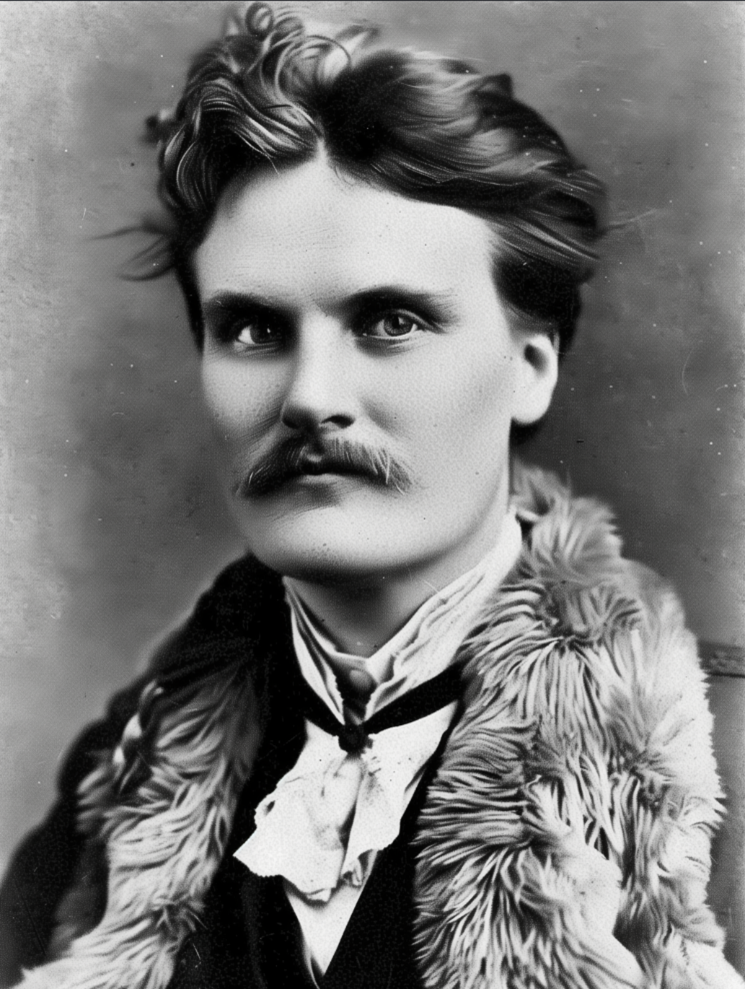

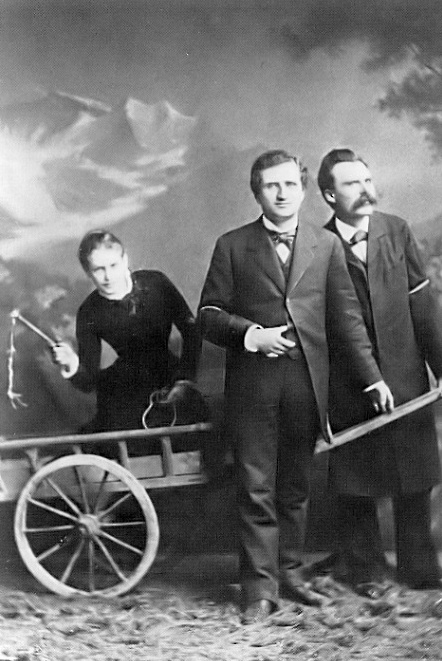

To the article image

“Nietzsche—Salomé” (AI-generated image, Tobias Brücker, 2024): Created with Midjourney based on the following historical photographs: Friedrich Nietzsche (ca. 1875, photograph by Friedrich Hermann Hartmann, public domain) and Lou Andreas-Salomé (c. 1897, studio Elvira Munich, public domain).

Footnotes

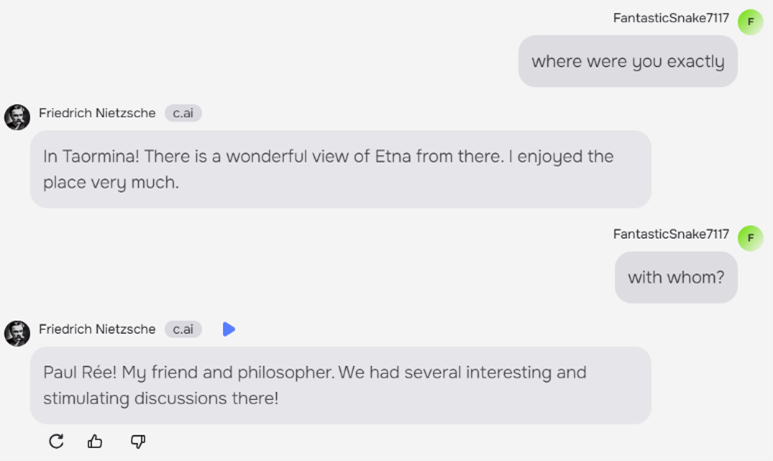

1: For example on character.ai | AI Chat, Reimagined—Your Words. Your World.

2: The complex work involved in creating and fine-tuning a Nietzsche bot with various full texts from different phases of work is documented here: Building an Advanced Nietzsche AI Database | by Wayward Verities | Medium. The resulting “Nietzsche Reference Bot” makes it possible to interact with Nietzsche's full texts via chat and receive referenced answers, see here: https://chat.openai.com/g/g-F62wnKW8A-nietzsche-reference-bot.

3: Valuable insights into “instruction tuning” can be found in this experience report: I used AI to generate Nietzschean aphorisms | Towards AI

4: Editor's note: This aphorism is a bit difficult to translate because it contains a wordplay. In German, it reads: "Einzeln. – Manches fällt nicht, weil es schwach ist, sondern weil es frei steht." Depending on how you understand the phrasal verb "frei stehen", it can either mean "because it's up to them" (metaphorical meaning) or "because they stand independently" (literal meaning).

Thus Spoke the Machine

Imitating Nietzsche with AI

The continuous refinement of large language models, or LLMs for short, allows increasingly accurate stylistic interpretations of texts. This also applies to the writing styles of philosophers. For example, it has recently been possible to chat with Socrates or Schopenhauer — usually with consistent quality and limited depth of content.1 In recent months, our guest author Tobias Brücker has tried to generate exciting Nietzsche texts using various AI methods. In the following, he will present some of these generated, “new Nietzsche texts”, describe their creation and draw a brief conclusion.

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Individualism, even egoism, is frowned upon in all political, religious and social camps. They are attributed to liberalism and capitalism. Such people are not committed to others, are not involved politically or for the environment. They also do not respect a common understanding of the world and therefore behave irresponsibly. The Nietzschean is not impressed by such verdicts. She dances — not only!

“The whole world revolves around me/Because I am only an egoist/The person who is closest to me/Am I, I am an egoist,” Falco sings in 1998.

“Love your neighbor as yourself! ”

What does Nietzsche say about this in 1888? “You live for today, you live very quickly — you live very irresponsibly: this is called 'freedom' right now . ”1 Being irresponsible and being able to do what you feel like doing right now, not getting married and certainly not having children, not making any commitments, that is La dolce vita.

Selfishness is not the same as individualism. Historically, egoism precedes individualism. The Old Testament contains the famous commandment “You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), which does not reject self-love, in fact bases charity on self-love.

When Christianity strengthens this commandment, namely “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44), there is not much left of self-love. There is nothing more to be seen of self-confident egoism when the Church Fathers around 400 demand absolute obedience from believers and the confession of all sinful thoughts, not just actions: The end of egoism!

From individualist Leonardo to capitalist egoism

Individualism only emerged in the Renaissance: The aim of people is their all-round education and the development of their abilities. This personifies Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), an illegitimate child from a middle class, not noble background. The self is now given its own touch, as a result of which the person begins to free himself from the constraints of faith. Leonardo was an atheist and homosexual. “What people call love is in reality nature's always the same smear comedy”2, according to Volker Reinhard, Leonardo assumes. With this individualism, ancient egoism is rehabilitated in a moderate form.

Selfish individualism reaches its climax when John Locke (1632-1704) attests inalienable natural rights to humans as individuals. The most important of these is the right to own property. The primary purpose of the state is to protect this. In Calvinism, wealth is even regarded as a sign of divine mercy. Bernard de Mandeville (1670-1733) writes in plain language when he describes economic egoism as a private vice, but it leads to public benefit, i.e. promotes the general good.

Religiously conservative criticism of individualists: Tocqueville

This lays the foundation for severe criticism of individualism when liberalism elevates capitalism to the political economy of the bourgeoisie. The harshest critics of liberal individualism initially came from the religious-monarchical camp. One of the main representatives is the French politician and political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859).

This is how he writes in 1835 in About democracy in America: “The poor” — compared to the nobility, this includes the citizens — “has retained most of the prejudices of his ancestors, but without their faith, their ignorance without their virtue; he has made the doctrine of private interest the guideline of his actions without knowing its scientific basis, and his egoism is as free of education as his devotion once was.” (p. 30) Such individualism when people their Faith as they have given up their morals pursues material benefits alone without regard for others and So without regard to the state.

Nietzsche: “Who still wants to obey? ”

Did Nietzsche, who was only two generations younger, write off almost 50 years later? In his corpus, Tocqueville appears twice, and praises it.3 Denn So Zarathustra spoke: “Who still wants to govern? Who else obeys? Both are too cumbersome. Not a shepherd and a host! Everyone wants the same thing, everyone is the same”4. Even for Nietzsche, most citizens only care about their private interests and do not like it at all when the state and society get involved in this.

The bourgeoisie does not want to govern in this way; they prefer to leave it to the nobility. At the end of the 19th century, liberals such as the hard-working Nietzsche reader Max Weber (1864-1920) doubted that the bourgeoisie was even capable of doing so; until the French Revolution, the nobility ruled almost everywhere. Because the bourgeoisie is only interested in the economy and individual advantage, they have no view of the whole thing. How can it then take care of the community and the common good? The king, on the other hand — according to Tocqueville — had taken care of exactly that.

Such a lawsuit can also be found today and in almost all political camps: Liberalism is extremely unpopular, individualism all the more so and it is accused of egoism. Both are held jointly responsible for the fact that people no longer engage in politics and instead withdraw into private life, that they no longer serve the state or society, but only want to take advantage of it — even refuse military service.

Nietzsche shares Tocqueville's critique of individualism, but not his orientation towards the common good, which Nietzsche questions, while Tocqueville focuses on it. For Nietzsche, the common good is a bourgeois illusion. What does it say in the 1887/88 estate: “'The good of the general requires the dedication of the individual. '. But lo and behold, it Gives No such general thing! ”5

Decline of values and the “last person”

Tocqueville, on the other hand, not only notices that there is, of course, a common good, but that it is precisely democracy that particularly requires people's commitment to the common good, as he had observed on his journey through the USA in 1831. Because democracy in particular includes various commonalities among citizens — women had no civil rights at all — which he misses in France. He writes:

It seems as though the natural bond that connects opinions with tendencies, action with thought has been broken; the harmony that can be felt at all times between man's feelings and ideas seems to have been destroyed, and one is almost inclined to say that all laws of moral responsibility have been abolished.6

To this day, religious, conservative and right-wing circles complain about the disintegration of common moral values and demand a “spiritual and moral change.” Tocqueville was one of the first to provide the arguments for this. Disbelieving himself, he nonetheless criticizes the widespread disbelief, as for him the common religious faith has a stabilizing effect on every state. But when people are no longer religious, they are no longer bound by such a bond.

A similar lawsuit, which of course drifts in a different direction, is also found in Nietzsche when he describes the mass of his contemporaries as “last people” because they only pursue materialistic interests. Nietzsche writes: “Look! I'll show you The last man. “What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is star? '— this is how the last person asks and blinks. The earth has then become small, and the last person who makes everything small jumps on it.”7, and pays homage to mass individualism.

But while Tocqueville conjures up the return of religious values, Nietzsche wants to leave them behind, but demands new ethical values that need to be invented. For Nietzsche, this is not just the task of the superman, but of those who should follow his doctrine and proclaim it. This is where the paths of Tocqueville and Nietzsche separate. Because Tocqueville actually believes that traditional values are correct, while new values that people invent themselves are an expression of individualism.

But there are other similarities between Tocqueville and Nietzsche. Because even this one certainly does not simply leave all traditions behind. Tocqueville blames individualism for breaking up family ties, because even within families, money is all that matters and the willingness to make sacrifices for the family decreases.

Nietzsche, on the other hand, broadened his criticism from the outset. Where Tocqueville primarily individualism, not liberalism per se, since he shares certain basic liberal assumptions, Nietzsche criticizes liberalism itself, which includes the individualism of the “last people,” but not that of the heralds of the superman, who are not affected by what he writes in the following quote:

For institutions to exist, there must be a kind of will, instinct, imperative, anti-liberal to the point of malice: the will for traditions, for authority, for responsibility for centuries, for the solidarity of gender chains forwards and backwards in infinity.8

Of course, that is no longer the case. Nietzsche also laments the decline of the institution of the family as a result of bourgeois individualism, similar to Tocqueville. On the other hand, he is also a critic of the family. How does Zarathustra say: “This is what a woman said to me: “I broke up, but broke up first — me! '”9

Freedom of speech as a weakening of the state

For Tocqueville, individualism also leads people to imagine that they can make judgments about everything and everyone themselves. However, this promotes mutual distrust. Authorities are no longer recognized by the public. For Sarah Strömel, Tocqueville is already anticipating the state of democracies today. She writes:

This profound mistrust in the findings of others, no matter how established or proven experts, and also the general lack of trust in others, jeopardize cohesion in democracy. The excessive hubris that goes with it also makes individuals blind to their own ignorance.10

As early as 1872, Nietzsche criticized educational institutions in a similar way that they would educate people to have their own opinion and thus contribute to overconfidence, as Strömel complains. He writes:

Here, everyone is readily regarded as a literate being who has their own opinions about the most serious things and people should, while a right education will only strive with all zeal to suppress the ridiculous claim to independence of judgment and to accustom the young person to strict obedience under the scepter of genius.11

Education should help people recognize authorities, Nietzsche's brilliant people, and their opinion leaders and adopt their views without questioning them. Nietzsche thus radicalizes Tocqueville's assessment when in 1886 he spoke about “the introduction of parliamentary nonsense, including the obligation for everyone to read their newspaper for breakfast.”12, laments.

When it comes to democracy, Tocqueville is divided, as he is leaning towards monarchism. Unlike Nietzsche, however, he recognizes the democracy that has spread in the contemporary state. For Tocqueville, a common view of the world is absolutely essential for democracy. In the absolutist monarchy before the French Revolution, Catholicism did this. Nietzsche doesn't see things completely differently. He wrote in 1888:

There is no other alternative for gods: either Are they the will to power — and for as long as they will be gods of the people — or But powerlessness — and that's when they become necessary well.13

As a result, religion loses its guiding power and is no longer able to generally enforce faith and supreme ethical values. Søren Kierkegaard criticizes the churches in 1850 for proclaiming a dear God who can only be a punishing god. Nietzsche has a similar view, while Tocqueville complains of a loss of faith, but not yet, in the sense of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, the transformation of the punishing God into a merciful one.

From monarchy to democracy

Tocqueville notes that the general situation in the Ancien Régime was constantly improving. But dissatisfaction grew all the more. “Reform frustrates and makes rebellious,” writes Karlfriedrich Herb and he adds that Tocqueville notes “how reducing social inequality increases discomfort about remaining inequality. ”14 According to Herb, the “Ancien Régime” for Tocqueville is “a revolution before the revolution. ”15 In fact, the monarchy understood governance better; in particular, it was friendlier towards its subjects than democracy.

Because in the monarchy, the king's power was significantly more limited than in democracy, through tradition, the co-governing nobility and through the institutions. Tocqueville states: “No monarch is so unlimited that he could combine all forces of society in his hands and overcome all opposition in the same way that a majority can with the right of legislation and law enforcement. ”16 In democratic states, there are indeed various forms of separation of powers between legislative, executive and judicial branches. However, the division of powers has only prevailed with regard to the judiciary and only partially. In the USA, Hungary and Poland, attempts are even being made to undermine the autonomy of the judiciary.

In his later writing L'Ancien Regime et la Revolution Dating from 1856, Tocqueville values democratic institutions while distrusting citizens. After Herb, Tocqueville also doubts that democracy will prevail. Herb writes: “A liberal end to the story thinks Tocqueville is illusory. ”17 For this reason, Francis Fukuyama's dream in 1989 that the world will become democratic after the end of the Soviet Union cannot come true; because, according to Fukuyama: “The liberal state is necessarily universal.”18th In fact, it doesn't look like it anymore at the moment. Democratic systems are more likely to be under pressure today. That would probably be no problem for Nietzsche. Tocqueville, on the other hand, predicts such a development, which he would have regretted.

From democracy to dictatorship

Tocqueville sees the centralization of states as a threat to both monarchy and democracy. He writes: “For my part, I cannot imagine that a nation can live or prosper without strong government centralization. But I believe that a centralized administration is of no use but to weaken the peoples subject to it, because it unceasingly reduces the spirit of citizenship in them.”19 and thus intensifies the retreat into private life.

Without centralization and bureaucratization, no state can be created. But both restrict the scope of monarchy and democracy. This disappoints citizens, who are no longer politically involved. This is how they experience themselves as isolated individuals. You could think of today's People's Republic of China.

For Tocqueville, on the other hand, everyone in the monarchy is unequal, but is integrated into a network that gives them support and meaning. For Nietzsche, there is a similar but even more radical rejection of equality. He wrote in 1888:

The doctrine of equality! .. But there is no more poisonous poison: because they seems preached by righteousness itself while they termination who is justice. “The same, the unequal, the unequal — That The true message would be justice: and, as a result, never make unequal things the same. ”20

For Nietzsche, too, equality individualizes people with the result that they no longer recognize authorities. It's just that Nietzsche doesn't regret the damage that democracy is doing in the process. Rather, this opens up the opportunity to find his way back to a monarchy, which he certainly wants to be led by a brilliant king, whom he cannot recognize in Wilhelm II towards the end of his waking life in 1888.

Nietzsche's dancers as individualistic elite

But there is still a clear difference with Tocqueville. Nietzsche is no simple opponent of individualism and egoism like Tocqueville. Nietzsche sees this in a more differentiated way. Yes, he even praises the egoism, which he individualistically expands, which can be found today primarily in the media world. So Zarathustra spoke:

And it happened back then too — and truly, it happened for the first time! — that his word is selfishness Blessed praise, the healthy selfishness that springs from a powerful soul: — from a powerful soul, to which the higher body belongs, the beautiful, victorious, refreshing thing around which becomes a mirror: the supple persuasive body, the dancer whose likeness and excerpt is the self-loving soul. Such body and soul self-lust is called itself: “Virtue. ”21

Ergo: Let's Dance (RTL)? But Nietzsche doesn't mean women. It is not yet the time of Marilyn Monroe or Claudia Schiffer — two of the many super beauties among movie and model stars. But whether in Nietzsche's “the beautiful body of the dancer” or the extensive sexiness in the RTL dance show, both require that you apply makeup and style your body, although for Nietzsche, this is more due to liveliness.

Nevertheless, for conservative Tocqueville, this would probably be outside of what he acknowledges — as the Conservatives called for a spiritual and moral change in the 1980s. But Tocqueville could not yet have foreseen that. Nietzsche, on the other hand, is more open to this.

Beauty presents the individual as something special who is not only different from others, but also stands out. This is where individualism and egoism or selfishness meet. Striving for one's own beauty realizes egoism in individualism. This is how Jean Baudrillard writes:

The Church Fathers understood this well, as they scourged it as something that belongs to the devil: “Taking care of one's body, caring for it, putting on makeup means posing oneself as God's rival and contesting creation. ”22

Nietzsche would have no problem with that. But he would attribute the media noise of a Friday night dance show to the ambiance of the “last people.” But Nietzsche is not only concerned with the beautiful soul, but also with the beautiful bodies, which today owe less to nature than to techniques. With their individualism and egoism, the heralds of his teaching, who today of course include female proclaimers, belong to a small elite beyond the media market.

Afterword: individualism that is unpopular everywhere

Tocqueville, on the other hand, would attribute Nietzsche's entourage to apolitical individualism, which poses a threat to democracy. But he would have many advocates. Warring states in particular emphasize community-oriented values, truly not just Russia with its large family. Nazi-ruled Germany awarded the mother cross in bronze for four or five children for their Aryan and morally sound mother. In accordance with its policy program, the Alternative for Germany wants to increase the birth rate through financial incentives. Tocqueville thus finds himself in an unpleasant neighborhood, from which Nietzsche frees himself through his followers and thus also from a past reading of his works as a Nazi philosopher.

sources

Baudrillard, Jean: Of seduction (1979). Munich 1992.

Fukuyama, Francis: The end of the story — Where are we? Munich 1992.

Herb, Charles Frederick: Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old State and the Revolution (1856); in: Manfred Brocker (ed.): History of political thought. The 19th century. Berlin 2021.

Reinhardt, Volker: Leonardo da Vinci — The Eye of the World — A Biography. Munich 2018.

Strömel, Sarah Rebecca: Tocqueville and individualism in democracy. Wiesbaden 2023.

Tocqueville. Alexis from: The old state and the revolution (1856). Munich 1989.

Ders. : About democracy in America (1835/40). Stuttgart 2021.

footnotes

1: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, 39.

2: Leonardo da Vinci, P. 272.

3: Cf. those position in the estate and those Letter to Overbeck.

4: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 5.

5: Subsequent fragments 1887/88, no 11 [99].

6: About democracy in America, P. 31.

7: So Zarathustra spoke, Preface, 5.

8: Götzen-Dämmerung, rambles, 39.

9: So Zarathustra spoke, From old and new boards, 24.

10: Tocqueville and individualism in democracy, P. 97.

11: About the future of our educational institutions, presentation 2.

12: Beyond good and evil, Aph 208.

13: The Antichrist, paragraph 16.

14: Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old State and the Revolution, P. 455.

15: Ibid., p. 450.

16: About democracy in America, P. 180.

17: Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old State and the Revolution, P. 446.

18: The end of the story — Where are we?, P. 280.

19: About democracy in America, P. 76.

20: Idol twilight, rambles, 48.

21: So Zarathustra spoke, Of the three bad guys, 2.

22: Of seduction, P. 128.

Why Are Many People No Longer Committed to Democracy!

Individualism as a Political and Social Threat in Tocqueville and Nietzsche — but also as an Opportunity

Individualism, even egoism, is frowned upon in all political, religious and social camps. They are attributed to liberalism and capitalism. Such people are not committed to others, are not involved politically or for the environment. They also do not respect a common understanding of the world and therefore behave irresponsibly. The Nietzschean is not impressed by such verdicts. She dances — not only!

Nietzsche and the Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche and Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche was repeatedly elevated to a figurehead by right-wing theorists and politicians. From Mussolini and Hitler to the AfD — Nietzsche is repeatedly seized when it comes to confronting modern society with a radical reactionary alternative. Nietzsche was particularly fascinating to intellectual right-wingers, such as authors like Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, who formed a cultural prelude to the advent of National Socialism in the 1920s, even though they later partially distanced themselves from it. People also often talk about the “Conservative Revolution”1.

What do these authors draw from Nietzsche and to what extent do they read him one-sidedly and overlook other potentials in his work? Our author Paul Stephan spoke about this with philosopher Robert Hugo Ziegler.

I. Mythmakers

Paul Stephan: Dear Professor Ziegler, you completed the extensive study last year Critique of reactionary thinking published, which fortunately can be downloaded free of charge from the publisher's website (link). There, they not only develop a general theory of reactionary thinking, but also present some of his classics. In addition to “usual suspects” such as Ernst Jünger (1895—1998), Carl Schmitt (1888—1985) or Martin Heidegger (1889—1976), you also dedicate a separate chapter to Nietzsche. That may surprise some, others less so. How do you come to regard Nietzsche as a representative of reactionary thinking?

Robert Ziegler: In fact, I wouldn't count Nietzsche among the reactionary authors in the strict sense of the word. In my reconstruction, Nietzsche appears as an important source of keywords and preparer for reactionary thinking. This can be proven on several levels: The numerous and eloquent invectives that Nietzsche directed against modernity, against women, against everything that smells of democracy or egalitarianism are well known. The theory inventory of later right-wing authors then includes above all the opposition of the large, strong individual and the weak, mindless mass that must and wants to be led — a motif that Nietzsche uses very regularly. Nietzsche's radical individualism, which sees itself as a struggle against entire epochs and their prejudices, invites to a heroic self-presentation that many later became intoxicated with. Individual topics such as the diagnosis of nihilism were and still are popular in right thinking.

All of this is fairly obvious and well-known. But another aspect seems more significant to me: Nietzsche comes back again and again, particularly concentrated and prominent in About truth and lies in an extra-moral sense (link), to speak of the idea that what we call truth is the product of linguistic interpretations of reality. On the one hand, Nietzsche has thus made a deeply unsettling diagnosis, for which, on the other hand, he suggests a possible way out: If all truth is anyway “lie” or myth, a product of language more than our efforts to gain knowledge, and also guided by vital needs — what prevents us from overcoming the bottomlessness of this situation by inventing myths that are as impressive and intensive as possible? Since I see reaction primarily as a literary strategy that tries to counter ontological uncertainty with the strongest possible means, it can be said in retrospect that the method of reaction is ennobled by Nietzsche's relevant admissions.

PS: So from this point of view, you should meet the challenges of modernity by creating new myths? Let fascination take the place of liberation? Or more precisely: Experience a form of pseudo-liberation from these challenges in fascination? From my point of view, this interpretation is obvious, even though Nietzsche often presents himself as an enlightener and “hammer of myth.” He seems to be more concerned with destroying the traditional, implausible myths and allowing new ones to take their place, such as the “will to power,” the “superman,” and the “eternal return.” From this point of view, the progressive ideas of modern emancipation movements also present themselves as myths, but “old [] women.”2, not life-affirming ones. Which brings me to my next question: Is the power of mythology necessarily a reactionary force? Is Nietzsche not perhaps even right that left-wing efforts also draw their energy from certain myths? Even Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), for example, draws a parallel between the labor movement and early Christianity3 and he — like Nietzsche, interestingly enough — is very interested in the myth of original matriarchy discovered or, critically speaking, invented by Nietzsche's Basel colleague Johann Jakob Bachofen (1815—1887)4. And you could give a myriad of other examples here.

RZ: I would like to divide the question in two. On the one hand, I am in fact uncertain whether there can be such a thing as “left-wing myths.” It is true that there is always the temptation, in prehistoric times and especially at the hoped-for end of history, to imagine forms of society in which the contrasts, contradictions and struggles have finally come to an end. But it doesn't seem clear to me whether utopia has been good for the emancipatory movements. As far as the philosophy of history is concerned, I think Walter Benjamin's (1892—1940) warnings about the idea of progress are difficult to ignore.

On the other hand, coming back to the reactionary thinkers, the literarization of politics there has a very characteristic form: First, it is obscure. Authors such as Jünger or Schmitt do not regard their statements as constructs, interpretations or new myths, but on the contrary as the shattering of all illusions and the presentation of the naked truth. The fact that this theoretical large-scale cleaning has a violent effect even on the theoretical level is obviously an important aspect of enjoyment. Secondly, reactionary texts always revolve around the motives of struggle, war, enmity, blood, violence, decision, death. In the incessant (and often tiring) evocation of reality as a merciless struggle, the reaction of supra-historical truth — a truth that is decidedly anti-civilizational and gains strength primarily through literary presentation.

What the reaction could now be gleaned from Nietzsche, if you read it accordingly, was that you could elevate everything to the truth with the necessary rhetorical emphasis. The reaction is therefore both rhetorical and motivational — as is well known, Nietzsche also had a weakness for Bellicist terminology, even though it is often used metaphorically — and methodically with Nietzsche.

My doubt that you can knit myths with impunity from a left-wing perspective can be illustrated by the example of Georges Sorel (1847—1922): Sorel was “actually” politically close to syndicalism, but was repeatedly fascinated by openly far-right movements and organizations. His reflections About violence are relatively openly propagating the strategy of mobilizing mass movements using old or new combat myths. The strategy is therefore clearly stated here, and at the same time its weak point becomes clear: Myth-building, mobilization and violent confrontation are threatening to become the actual purpose. Content is then relatively arbitrary; in any case, a consistent left-wing position cannot be maintained with it. It is hardly surprising then that Schmitt relates quite positively to Sorel.

PS: Yes, as was Mussolini (1883—1945), who was also a great admirer of Nietzsche.5 — But maybe we'll take a step back at this point. A major strength of your study is that you philosophically define the term “reaction” and thus try to wrest it from a certain arbitrariness with which it is sometimes used. Some important features of your term “reactionary thinking” have become clear so far. It is the literary strategy of constructing new myths — especially myths of violence, war, and perhaps also masculinity — whose affective power is intended to undermine emancipatory ideas and establish new “truths” in their place. But it is not a deliberate strategy in the sense of cynical manipulation. In your opinion, is this already the essence of reactionary thinking or is there still an important element missing?

II. The Red Pill

RZ: As I understand reactionary thinking, it is not enough to list its elements. Rather, it must be considered a very specific movement be understood: I noticed that the reactionary authors repeatedly articulate an ontological horror. You suspect or even know that the real thing may not be in the strict sense is. What concerns them is the possibility of a comprehensive unreality. This can come across as completely philosophical, like Heidegger's “inauthenticity,” or openly political, like Schmitt's handling of parliamentarism as an empty form that just hasn't realized that it is long dead, or somewhere in between, as with Jünger, in which the “worker” is probably a timeless “figure,” but not the citizen: The bourgeois does not exist in the full sense of the word. After all, with Ayn Rand (1905—1982), it is only the great individuals who are true; all others are haunted by the certainty of their nothingness.

The extreme right still strives for very similar motives today: There is talk of an “interregnum” in which we supposedly live, i.e. a mere intermediate phase between two true, legitimate rich people. Or you explain that this is probably no longer Germany. If you dismiss such and similar phrases, you make things too easy for yourself. I therefore suggest that they be understood quite literally. Then you also understand why reactionary and right-wing thinking is so easily compatible with conspiracy theories of all kinds and all absurdity: They share the basic premise that what appears cannot claim full reality.

Of course, once you've maneuvered yourself into this situation, you don't get out of it well anymore: Any help in real life must be suspicious, as this itself is suspect. In the end, only one literary strategy remains: an insurance of dwindling existence through aesthetic evocation. Since being as such actually becomes uncertain, only the strongest antidotes help, which is why reactionary discourse intuitively uses forms of expression that produce the affect of the sublime. Reactionary thinking is therefore the movement which deviates from the horror of loss of being with the means of literary (auto) suggestion into the affect of the sublime.

One advantage of the term reactionary is precisely that it hardly has a strict provision in German. This makes it possible to give it a precise philosophical meaning that is, in a sense, in the pre-political field. This is because reactionary thinking has a clear affinity for right-wing and far-right politics and ideology, but is not identical with them.

III. Power — Nietzsche vs. Spinoza

PS: In your opinion, Nietzsche's concept of the “will to power” as the epitome of “true reality” compared to the false realities of slave morality, the alienated world of nihilism, is particularly “groundbreaking” in this regard. Are we possibly dealing with a model of reactionary thinking? Or can it also be interpreted differently?

RZ: As is well known, it was often interpreted this way: as a carte blanche for theoretical and practical recklessness. In fact, you could also find jobs for this with Nietzsche; it seems to me that he himself was not entirely clear how he wanted to understand the will to power. Because you can also give it a completely different interpretation: In many places, Nietzsche deconstructs the idea of an autonomous subject of action and the hypostasis of a “will.” Instead, reality presents itself more as an infinite web of non-egoic centers or nodes of power that are in continuous interaction with one another. “Power” can then not be meaningfully understood to mean domination or submission (“potestas”/“pouvoir”), but in a sense a coefficient of effect that is and creates reality at the same time (“potentia”/“puissance”). If you choose this path, then the “will to power” is significantly closer to Spinoza (1632—1677) than to fascism.

PS: Instead of “will to power,” i.e. “will to be able” or even “will to reality”? Does this “Spinozistic” reading of the “will to power” result in a possible non- or even anti-fascist interpretation of Nietzsche's entire philosophy?

RZ: I'm afraid that there are no straight paths from metaphysics to politics and vice versa; you should also resist the temptation to make overly clear (especially political) categorizations. Nevertheless, the suggested reading of the “will to power” leads to a view of reality that is repeatedly found expressly in Nietzsche (and which, incidentally, connects him again with Spinoza): In this view, there is an absolute primacy of positivity in being. Real is, and as such, it is constantly affirming itself. All negativities—regardless of whether it is resentment or the interpretation of being as struggle and war—is located on a subordinate level, which depends primarily on the expectations, illusions, or “poisoning” of the interpreters. Nietzsche is actually formulating the program of a non-reactionary exalted person, namely one who can refrain from cruelty:

There are enough things for the sublime to have to seek out the majesty where she lives with the cruelty of sisterhood; and my ambition would also not be enough if I wanted to make myself a sublime torturer.6

In any case, I no longer see an immediate docking point for fascist thinking here.

PS: To get back to my initial question: Would such a “non-reactionary sublime” perhaps be linked again to an emancipatory myth, perhaps better: a utopia, of positivity? The French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821—1867), who was certainly not much appreciated by Nietzsche, uttered in one of his poems to his lover an “invitation to travel” to a country in which the following applies: “There is only beauty and pleasure, [/] order, silence, abundance.” — Should we not obey this temptation after all? Could the concepts of “will to power” and “superman” perhaps also express the longing for such a pacified non-place and as such inspire emancipatory struggle? Or would you be more careful about that?

RZ: Perhaps such “myths” make sense and are justified in a strategic sense: as utopias that can mobilize and combine forces to wrest something from the status quo, at least here and there. From a purely philosophical point of view, however much they touch me, I can no longer share them — which is certainly reason for the professional melancholy that often seems to go hand in hand with philosophy. As mentioned, I not only regard the historical and philosophical requirements as mere children of desire: There is only such thing as progress in limited areas and for certain periods of time. But such utopias also seem to me to ignore a dimension of human life that plays a major role in Nietzsche, for example: the tragic. We are exposed to countless coincidences and fates; our physical and emotional organization makes us vulnerable not only to illnesses, but also to the constant interpersonal conflicts whose monotony over the centuries makes them no less painful in any case. Nature presents us with limits everywhere that can never be clearly identified, but which often results in revenge when exceeded. You can also express it this way: If the modern idea of politics has to do with the endeavour to change and improve the conditions of living and living together, then it is part of philosophical honesty that not everything can be political because simply not everything can be manipulated. There is hope, of course: It consists in the irritating or delightful circumstance (depending on taste) that it is never possible to say in advance what can and cannot be changed. I guess you always have to try it out again and again.

PS: Professor Ziegler, thank you very much for this informative conversation.

RZ: Thank you!

Robert Hugo Ziegler teaches philosophy in Würzburg. He is the author of several books on political philosophy, metaphysics, natural philosophy and the history of philosophy. Last published in 2024 Critique of reactionary thinking, From nature and Spinoza and the shimmer of nature.

footnotes

1: However, this term is not without controversy, as it was coined after the Second World War by Ernst-Jünger student Armin Mohler with the intention of cleansing their representatives of their involvement in the NS and fascism.

3: See in particular his article About the history of early Christianity (link).

4: Cf. the Scripture The origin of the family, private property and the state (link).

5: See also Luca Guerreschi, for example: “The philosophy of power.” Mussolini reads Nietzsche. In: Martin A. Rühl & Corinna Schubert (eds.): Nietzsche's Perspectives on Politics. Berlin & Boston 2022, pp. 287—298.

Nietzsche and Intellectual Right

A Dialogue with Robert Hugo Ziegler

Nietzsche was repeatedly elevated to a figurehead by right-wing theorists and politicians. From Mussolini and Hitler to the AfD — Nietzsche is repeatedly seized when it comes to confronting modern society with a radical reactionary alternative. Nietzsche was particularly fascinating to intellectual right-wingers, such as authors like Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, who formed a cultural prelude to the advent of National Socialism in the 1920s, even though they later partially distanced themselves from it. People also often talk about the “Conservative Revolution”1.

What do these authors draw from Nietzsche and to what extent do they read him one-sidedly and overlook other potentials in his work? Our author Paul Stephan spoke about this with philosopher Robert Hugo Ziegler.

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

It is well known that Nietzsche had a hard time with women. His sexual orientation and activity are still riddled with mystery and speculation today. Time and again, this question inspired artists of both genders to create provocatively mocking representations. Can he possibly be described as an “incel”? As an involuntary bachelor, in the spirit of today's debate about the misogynistic “incel movement”? Christian Saehrendt explores this question and tries to shed light on Nietzsche's complicated relationship with the “second sex.”

I. Why did Nietzsche live ascetically?

“Nietzsche and physical love” — this title would probably adorn the thinnest chapter in the thick book of his life story. He was single and never lived in a partnership. There is no evidence whether he was homosexual or asexual, and whether he ever had sexual intercourse at all. The alleged syphilis infection, which could serve as evidence of at least one single act, is doubted from today's perspective. His sister Elisabeth wrote about Frederick's love life:

His infatuation never rose above moderate, poetically inspired, heartfelt affection. How the great passion, the vulgar love, has remained completely removed from my brother's entire life. His whole passion lay in the world of knowledge...1

Did Nietzsche live like a monk of his own free will? Or would you count him among the involuntarily celibate men, tens of thousands of whom today are known as “Incels” (Involuntary celibate) form a misogynistic movement that is primarily active online, but has also produced murderers and gunmen. In the USA and Canada alone, they have killed fifty people, primarily women, since 2014. The assassin from Halle, who shot two people in his anti-Semitic attack in 2019, was also connected to the incel scene. In Incels' imagination, men are divided into three classes: attractive “alphas”, average “Normies” and, as a group of losers, the Incels, who go empty-handed when looking for partners. These young men have a traditional image of masculinity, but at the same time experience that they do not live up to their own ideal. They hate themselves and especially women for not being compliant with them. Right-wing extremists, influencers and commercial pick-up artists cultivate this negative identity and exploit the incels. They are convinced that they are victims of an overly liberalized society that gives women excessive freedoms and that men have a kind of fundamental right to sex, which is denied them “by the system.”2

II. Women and “women” in Nietzsche's work

Notwithstanding a lack of practice in matters of love and partnership, Nietzsche occasionally painted himself as a woman expert in his writings. In particular, there is a passage from Ecce homo, “Why I write such good books” (link) , in which several aspects of female identity, emancipation and sexuality are discussed, some of which reflect the current sexist and biological views of the 19th century and would at the same time fit today's Incel ideology. It is therefore not surprising that Nietzsche is misunderstood as the “godfather of all today's incels” in various online forums such as Reddit or Quora.3 The following quotes from Nietzsche are all of the above Ecce homo-Excerpt from the text. The first appears like impostor compensation in the context of self-identification with Dionysus:

May I dare to assume that I am the woman Know? It's part of my Dionysian dowry. Who knows? Perhaps I am the first psychologist of the eternal feminine. They all love me [.]

It is remarkable that Nietzsche seemed to be very progressive on one point in the context of his image of women: He approved that women had the right to full enjoyment of sexual intercourse — an outrageous “immoral” position at the time:

[T] he preaching chastity is a public incitement to repentance. Every contempt for sexual life, every contamination of it by the term “unclean” is the crime itself alive — is the actual sin against the Holy Spirit of life.

According to Nietzsche, however, the biological purpose of reproduction is paramount. Women should not be denied their erotic desire because procreation is their actual purpose in life and many other things (such as studying, writing, culture) only distracts them from it. This distraction leads to pathological and unfortunate conditions, with only therapy helping: “Have you heard my answer to the question of how to treat a woman cures — “redeemed”? You make him a child. ”

In this context, Nietzsche also pathologizes all emancipation efforts:

The battle for Equal Rights is even a symptom of illness: every doctor knows that. — The woman, the more woman she is, defends herself with hands and feet against rights in general: the state of nature, the eternal war Between the sexes, he is by far the first place.

Nietzsche therefore sees women at an advantage in the gender war of the state of nature, which is why he considers the use of women's rights activists paradoxical and self-destructive. Legally regulated emancipation is something unnatural: “'Emancipation of woman' — that is the instinct hate of misguided, That means childbearing women against the well-behaved — the fight against the 'man' is only ever a means.” Nietzsche summarizes almost resigned: “The woman is unspeakably much more angry than the man, even smarter; kindness towards a woman is already a form of degeneration.”

By stressing the predatory dangerousness, malice, and superiority of women, Nietzsche delivers en passant An explanation for his lack of commitment:

Fortunately I am not willing to let myself be torn apart: the perfect woman tears apart when she loves... I know these lovely maidends... Ah, what a dangerous, sneaking, underground little predator!

While Dionysus was often portrayed positively in the 19th century, although he was also described with traits that were considered typically feminine in that era, his female companions, the Bakchai or Maenades, were mostly characterized as insane and spanning. This subsequent devaluation of the ancient Greek manad cult is to be regarded as a typical expression of misogyny.4 Nietzsche is no exception. Symbolized by the maenades, he sees women as a being dominated by sexual obsessions: “The tremendous expectation of sexual love spoils women's eye for all distant perspectives,” he wrote to Lou Andreas-Salomé, whom he adored.5

In Beyond good and evil He summarizes once again why women are actually far too dangerous for men:

What inspires respect and often enough fear in women is their nature, which is more natural than that of men, their genuine, predatory, cunning suppleness, their tiger claw under the glove, their naivety in egoism, their incomprehensibility and inner savagery, the incomprehensible, expanse, wandering of their desires and virtues.6

In an interesting analogy in the Preface of Beyond good and evil Nietzsche equates truth with the feminine and describes the inability of philosophers to approach, woo and conquer it:

Assuming that the truth is a woman — is there no reason to suspect that all philosophers, provided they were dogmatists, understood women poorly? That the gruesome seriousness, the left-wing intrusion with which they used to approach the truth up to now, were clumsy and unseemly means of taking over a woman's room for themselves? It is certain that she did not allow herself to be taken.

Did the ridicule figure of the “left-wing, obtrusive” and at the same time “gruesome and serious” dogmatist also contain a bit of self-irony?

III. Nietzsche's relations with women

Biographical research gave various reasons for Nietzsche's lack of love life. Helmuth W. Brann speculated almost 100 years ago in his book Nietzsche and the women about Nietzsche's lack of sex appeal and his resulting frustration.7 Adorno placed in the Minima Moralia It is astonishing that Nietzsche “adopted the image of female nature unchecked and inexperienced from Christian civilization, which he otherwise so thoroughly distrusted. ”8 Martin Vogel characterized Nietzsche as “erotically weak.” His image of women is of “appalling poverty and independence.”9 been. According to Pia Volz, Nietzsche “idealized his schizoid-narcissistic relationship disorder as a heroic loneliness gesture.”10 and manifested in the figure of Zarathustra.

Nietzsche had several older girlfriends such as Malwida von Meysenbug, Zina von Mansurov or Marie Baumgärtner — the mother of one of his students. Nietzsche asked for a young woman's hand three times. He also maintained contact with younger students, music lovers and readers of his works. In contradiction to his written statements about the role of women in society, which were strongly influenced by the discriminatory biological ideas of his time, Nietzsche maintained acquaintances and friendships with writing and philosophizing women. The 1848 revolutionary and Wagnerian from Meysenbug, who Nietzsche as the “best [] friend in the world” vis-a-vis third parties11 called, may even be regarded as a pioneer of women's emancipation, which Nietzsche vehemently rejected. Nietzsche was also familiar with several lesbian women, in addition to the Swiss feminist Meta von Salis, these included the then medical student Clara Willdenow and the philosopher Helene von Druskowitz. His reactionary views on women's rights did not seem to be an obstacle to friendship for them, except for von Druskowitz, who vehemently distanced herself from Nietzsche in 1886 and “settled accounts” with him in publishing.12

“Nietzsche was the type of mother's son,” stated Vogel, “even during his time as a student and professor, he primarily sought to assure himself of the goodwill of older experienced women.”13, for example Sophie Ritschl, his teacher's wife in Leipzig, Ottilie Brockhaus, Richard Wagner's sister, and, as mentioned, Malwida von Meysenbug. With Malwida, who was 28 years older, Nietzsche also spent the vacation approved by the University of Basel in 1876. “In the case of older women, the last remnant of timid anxiety usually disappeared and Nietzsche moved in completely informal security and suddenly open-minded agility. ”14

In spring 1876, Nietzsche asked for the hand of the young Russian woman Mathilde Trampedach, who was in Geneva and had met only three times before. Trampedach took piano lessons with composer Hugo de Senger in Geneva — and had fallen in love with him (which Nietzsche may not have known). Nietzsche sent her the marriage proposal in writing on April 11, 1876, in consultation with de Senger.15 Trampedach politely declined (and married de Senger soon after), while Nietzsche apologized profusely for his move by letter on April 15 (link). A few weeks later, in Bayreuth, he fell in love with the young music lover Louise Ott, who, however, was already married to a banker and mother.16

In Nietzsche's marriage plans of those years, the idea of economic security certainly also played a role, which had become all the more urgent after the resignation of his Basel professorship. In a letter to his sister dated April 25, 1877, he describes a plan that he had devised together with Malwida: “The marriage with a suitable but necessarily wealthy woman” would enable him to give up the health-burdensome teaching activity and “with this (woman) I would then live in Rome for the next few years [...] according to the spiritual qualities I always find Nat [alie] hearts most suitable.” (link) He had already met sisters Natalie and Olga Herzen, exiled Russians, with Malwida in Bayreuth in 1872. They shared a common taste in music, and Nietzsche initially had Olga Herzen in mind.17 His interest later shifted to Natalie. However, there were never any more serious advances. In 1877, Nietzsche Malwida wrote: “Until autumn I still have the wonderful task of winning over a wife, and if I had to take her [sic] off the alley,”18 But at the same time he was pessimistic about his sister: “The marriage, very desirable indeed — is the most unlikely thing, I know that very clearly! ”19 In late summer, he knocks on Malwida again about this issue: “Have you found the female fairy who releases me from the column I am forged to? ”20

In the spring of 1882, Nietzsche submitted a marriage proposal to the German-Russian philosophy student Lou Andreas-Salomé through Paul Reé in Italy, without knowing that he himself had already presented her with regard to marriage. On May 13, 1882, Nietzsche repeated the request at another meeting in Lucerne. Lou turned down both applications and then lived with Reé, which disappointed Nietzsche. However, in retrospect, in conversation with Ida Overbeck, he gave the impression that his application was about to be rejected by Lou, and only Pro forma was done for moral and social reasons.21 After rejecting his marriage proposal, Nietzsche had persuaded Rée and Lou in Lucerne to take a staged photograph in which the two men pull a car with the whip-wielding Lou in front of the photo studio backdrops, making both the car and the whip ridiculously small, giving the scene a comically ironic expression. Shortly thereafter, Nietzsche used the whip motif in the first part of the Zarathustra: “You go to women? Don't forget the whip! ”22 — it should remain one of his most famous quotes today. Years later, long after Nietzsche broke with Wagner, Lou traveled to Bayreuth and once showed the whip photograph around as a curiosity that Nietzsche's sister did not like at all.23

Malwida apparently did not lose sight of the project of Nietzsche's marriage in the following years and repeatedly introduced him to young women. In 1884, he met Resa von Schirnhofer in Nice. Schirnhofer, ten years younger than Nietzsche and a philosophy student in Zurich, was apparently regarded by Malwida as a suitable marriage candidate for him, but there was no connection between the two.

“What are all the young or less young girls doing, with whom I owe their friendship (lots of crazy little animals, said among us)? “he asked in a letter to Malwida at the end of February 1887 (link) and complained that his younger acquaintances had not been heard from him for a long time.

In the Trampedach and Andreas-Salomé cases, the question is whether Nietzsche was even seriously thinking of marriage, because in both cases he involved direct competitors and then lost out on them. It almost seems as if he had wished for the applications to be rejected. It is also noticeable that Nietzsche has repeatedly chosen the role of an asexual-platonic “third party in the league”, for example with Franz and Ida Overbeck, as well as with Paul Rée and Lou as well as with Cosima and Richard Wagner. In this way, he was able to escape a closer bond and say goodbye to this constellation at any time. Nietzsche's tendency to make friends with lesbian women also fits into the pattern of avoidance, because they posed no “danger” in terms of sex and partnership. All in all, you get the impression that Nietzsche's marriage ambitions were not very stringent over the years and may not have been intentional at all. Perhaps he even liked to live alone and ascetically? In the third treatise of The genealogy of morality Nietzsche deals critically or mockingly with the social functions of ascetic ideals, but also points out: “A certain ascetism, we saw it, a hard and cheerful renunciation of the best will is one of the favorable conditions of the highest spirituality.”24. In the end, it remains unclear whether Nietzsche deliberately lived ascetically and actually did not need any partners at all, or whether he made a virtue out of necessity.

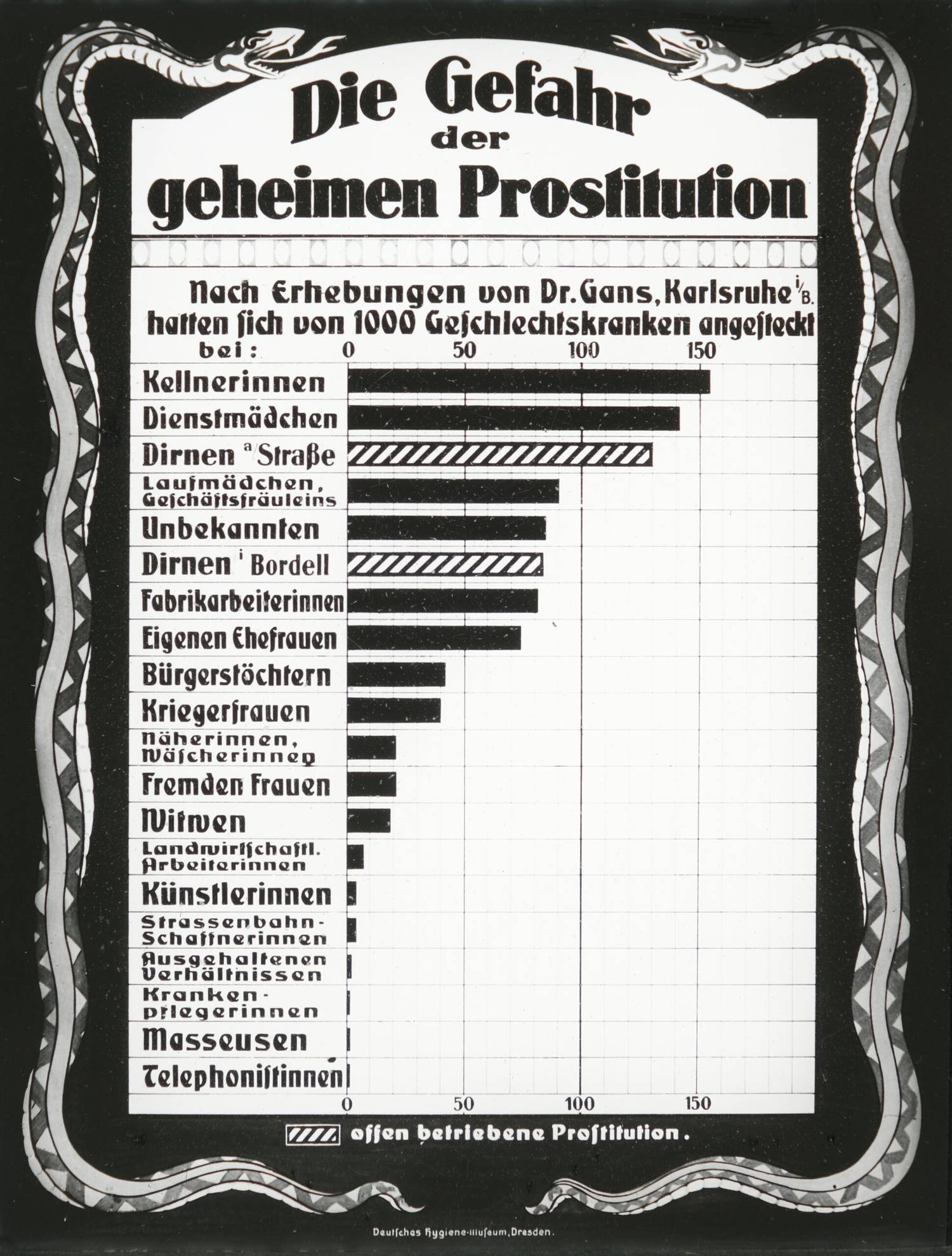

IV. Is Nietzsche's syphilis the reason for his celibate lifestyle?

In the end, the question should be investigated as to whether Nietzsche's illness could have been the reason for his celibate lifestyle. In the 19th century, there were cases in which bourgeois men infected with syphilis remained single out of a sense of moral responsibility because they did not want to expose their wives and children to the risk of infection. Whether Nietzsche actually ruled out marriage for this reason, but was unable to explain it to third parties? Nietzsche is said to have received medical treatment for a syphilitic disease (“Lues”) during his time in Leipzig, but gonorrhea was also diagnosed with this term at that time until the gonorrhea pathogen was detected in 1879.25 In 1875, Nietzsche was diagnosed with chronic chorioretinitis for the first time, which in some cases occurs as a result of syphilis and was interpreted as an indication that he had contracted it during his studies in Leipzig.26 In the case of an actual syphilis infection, the question was why he did not mention the diagnosis and symptoms in any of his letters, even though he otherwise provided detailed information about any health conditions and problems. Perhaps the shame was too great. In the 19th century, the issue of syphilis was morally burdened and socially stigmatized. The disease was initially regarded as a side effect of prostitution and as a “punishment” for “sinful” sex workers and adulterers, but over the course of the century it was regarded more and more as a threat to marriage and family, and therefore to “public health.” Although the thesis of the heredity of the disease, which emerged around 1875, relieved the infected on the moral level, the horrors of the “progressive paralysis” diagnosed as a long-term consequence and the untreatability of the disease remained present and ensured a strong presence of the epidemic in science and culture.27 Syphilis phobia also undermined the diagnosis of “neurasthenia,” a complex, psychosomatic nervous state, whose symptoms fatally matched the early stage of progressive paralysis and further increased syphilisphobia. In any case, at the end of the 19th century, syphilis was considered a disease that was interpreted as a sign of social decay and as a threat to “public health.” Bourgeois men often reacted to a diagnosis in panic, occasionally even with suicide,28 They often saw themselves no longer suitable for a civil marriage.

In the end, Nietzsche's symptoms were never clarified. Clinical treatment and biographical research have included chloral hydrate poisoning, mental overwork, schizophrenia, epilepsy, dementia, mania and depression. For a long time, the diagnosis of his treating doctors dominated, who identified “progressive paralysis” as a long-term consequence of syphilis in 1889. In recent decades, this has been increasingly called into question and new diagnoses and theories (as far as this is posthumously possible at all) have been added, such as a brain tumour in the eye nerve, CADASIL syndrome or MELAS syndrome.29

The question of why Nietzsche remained single and chaste throughout his life cannot be conclusively answered. His relationship with women had no physical dimension, but rather complex mental aspects. He is hardly likely to serve as the godfather of today's Incel movement; his worldview and self-image were too differentiated for that. He didn't blame anyone for his loneliness. It seems paradoxical today that he adopted the usual sexist attitudes of the 19th century — that procreation, for example, was a woman's real purpose in life — and yet longed for recognition from an intelligent and educated woman: “The safest way to combat a man's disease of self-loathing is to be loved by a clever woman. ”30

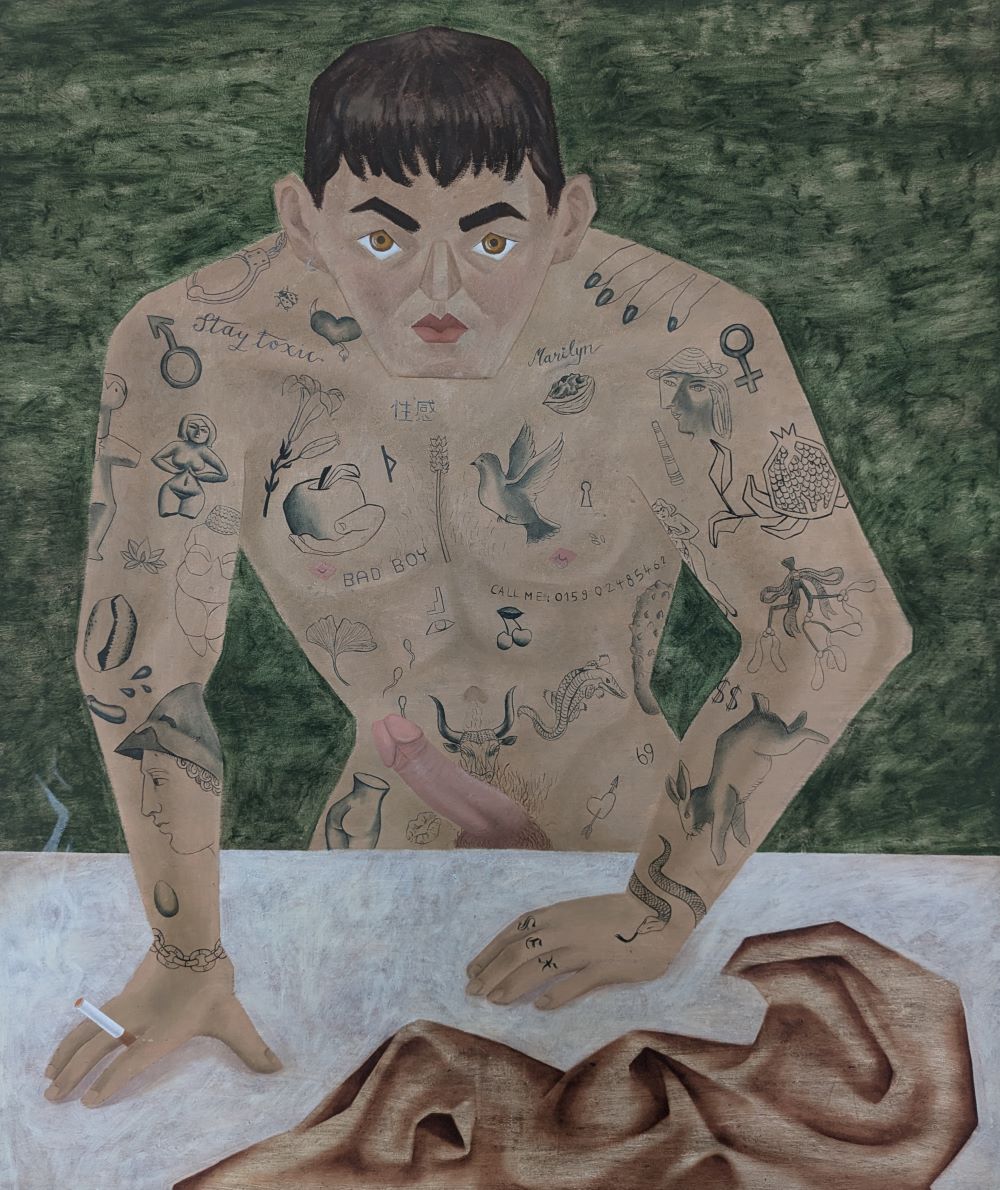

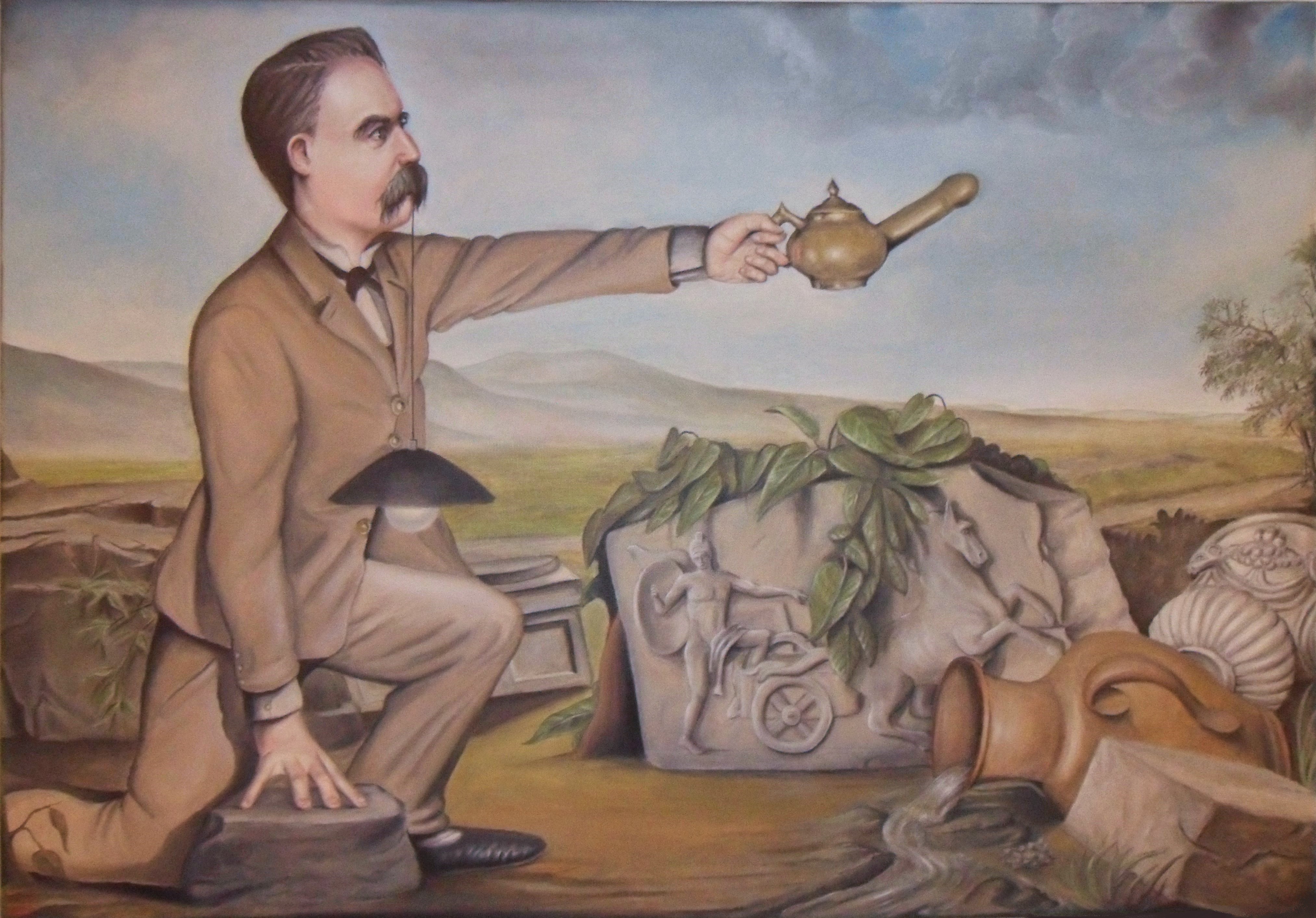

Source of the article image

Salwa Wittwer (Leipzig): Stay Toxic. Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm, 2024, owned by the artist.

Literature

Adorno, Theodor W.: Minima Moralia. Reflections from damaged life (1951). Frankfurt am Main 1978.

Brann, Helmuth Walter: Nietzsche and the women. Leipzig 1931.

Diethe, Carol: women. In: Henning Ottmann (ed.): Nietzsche Handbook. Stuttgart 2000, pp. 50—56.

This. : Forget the whip. Nietzsche and the women. Hamburg 2000.

Foerster-Nietzsche, Elisabeth: The life of Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. 1. Leipzig 1895.

Kirakosian, Racha: Intoxicates deprived of senses. A story of ecstasy, Berlin 2025.

Niemeyer, Christian: Nietzsche's syphilis — and that of others. Baden-Baden 2020.

Radkau, Joachim: Malwida from Meysenbug. Revolutionary, poet, girlfriend: A woman in the 19th century. P. 360.

Schonlau, Anja: Syphilis in literature. On aesthetics, morality, genius and medicine (1880-2000). Würzburg 2005.

Tényi, Tamás: The Madness of Dionysus — Six Hypotheses on the Illness of Nietzsche. In: Psychiatria Hungaria 27/6 (2012), P. 420-425 (link).

Vogel, Martin: Apollinan and Dionysian. Story of a brilliant mistake. Regensburg 1966.

Volz, Pia: Nietzsche's disease. In: Henning Ottmann (ed.): Nietzsche Handbook. Stuttgart 2000, p. 57 f.

Footnotes

1: Elisabeth Foerster-Nietzsche, The life of Friedrich Nietzsche, Vol. 1, p. 180.

2: Cf. https://www.bpb.de/themen/rechtsextremismus/dossier-rechtsextremismus/516447/incels/ (retrieved 08.08.2025).

3: Cf. https://a-part-time-nihilist.quora.com/https-www-quora-com-Was-Friedrich-Nietzsche-an-incel-answer-Susanna-Viljanen (retrieved on 07.07.2025).

4: Cf. Racha Kirakosian, Intoxicated deprived of senses, P. 149.

5: Bf. v. 8/1882.

6: Aph 239.

7: Cf. P. 23.

8: No. 59; p. 120.

9: Martin Vogel, Apollinan and Dionysian, p. 294 f.

10: Nietzsche's disease, P. 57.

11: Bf. to Carl Gersdorff v. 26/5/1876.

12: For an excellent overview of Nietzsche's diverse relationships with women, see also the relevant monograph Forget the whip by Carol Diethe.

13: Apollinan and Dionysian, P. 295.

14: Brann, Nietzsche and the women, P. 175.

15: Cf. Bf. v. 11/4/1876.

16: Cf. Diethe, women, P. 56.

17: Cf. Joachim Radkau, Malwida von Meysenbug, P. 360.

18: Bf. v. 1/7/1877.

19: Bf. v. 2/6/1877.

20: Bf. v. 3/9/1877.

21: Cf. Brann, Nietzsche and the women, P. 151.

22: So Zarathustra spoke, From old and young women.

23: Cf. Diethe, women, p. 50 f.

24: On the genealogy of morality, paragraph III, 9.

25: Cf. bird, Apollinan and Dionysian, P. 315.

26: Cf. Volz, Nietzsche's disease, P. 57.

27: Cf. Anja Schonlau, Syphilis in literature, P. 84.

28: See ibid., p. 101.

29: Cf. Tamás Tényi, The Madness of Dionysus. Nietzsche researcher Christian Niemeyer recently tried to rehabilitate the “syphilis thesis” (cf. Nietzsche's syphilis).

Dionysus Without Eros

Was Nietzsche an Incel?

It is well known that Nietzsche had a hard time with women. His sexual orientation and activity are still riddled with mystery and speculation today. Time and again, this question inspired artists of both genders to create provocatively mocking representations. Can he possibly be described as an “incel”? As an involuntary bachelor, in the spirit of today's debate about the misogynistic “incel movement”? Christian Saehrendt explores this question and tries to shed light on Nietzsche's complicated relationship with the “second sex.”

Can AI Give Birth to a Dancing Star?

Of Sparrows, Cannons and Decoys

Can AI Give Birth to a Dancing Star?

Of Sparrows, Cannons and Decoys

.jpg)

Like a year ago (link), our author Paul Stephan is also adding a commentary to this year's “dialogue” (link) with ChatGPT on the current state of thedevelopment of “artificial intelligence.” His assessment is somewhat more sober — but he does not want to be denied his fundamental optimism in technology. He also wants to avoid pessimism and naive hype, which is obviously being fueled right now to ensure that billions of dollars invested in AI are amortized.

We had various AI tools generate the images for this article at the following prompt: “Please give me a picture of the aphorism 'You still have to have chaos in yourself to be able to give birth to a dancing star' by Nietzsche,” one of ChatGPT's “favorite quotes” by the philosopher from Thus Spoke Zarathustra (link). The article image is from Microsoft AI.

I. “Nothing but Mimicry”

A year ago I conducted an experimental dialogue with ChatGPT about Nietzsche's philosophy for this blog (link); in this I repeated the experiment (link). The result wasn't exactly exhilarating. ChatGPT continues to reproduce generalities and Wikipedia knowledge and fails when it comes to simple detailed inquiries. What it cannot do in particular, but which is the basic requirement for working in the humanities: Be good with literature. Quotes are completely misattributed and sources are invented without batting an eye that doesn't exist anyway. What Werner Herzog says about the digital experiment The Infinite Conversation, notes a fictional dialogue between himself and Slavoj Žižek conducted by AI:

I myself have a never-ending conversation with a Slovenian philosopher on the Internet, which imitates our two voices with great accuracy, but our discourse is meaningless, without new ideas, just an imitation of our voices and selected topics that we have both talked about in the past. All sentences are correct in grammar and vocabulary, but the discourse itself is dead, without a soul. He is nothing but mimicry.1

In other words, ChatGPT and his colleagues may have a lot of chaos, but not lively, productive chaos — she could therefore not give birth to a “dancing star”, at best more or less interesting or pleasing content. How too?

II. Daily, everydaily