“It is no longer about monumentalization! Artists today want to make Nietzsche human so that one can deal with him in a new way.”

Interview with Barbara Straka about Her Book Nietzsche Forever?

Discussion with Barbara Straka

Interview with Barbara Straka about Her Book Nietzsche Forever?

Last year, curator and art historian Barbara Straka published a two-volume monograph entitled Nietzsche forever? Friedrich Nietzsches Transfigurationen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst (Nietzsche Forever? Friedrich Nietzsche's Transfigurations in Contemporary Art), in which she explains Nietzsche's significance for the visual arts of the present day. After Michael Meyer-Albert dedicated a two-part review to her work in recent weeks (part 1, part 2), here follows an interview conducted by our author Jonas Pohler with the author in Potsdam. He discussed her book with her, but also about the not always easy relationship between philosophy and contemporary art.

1. “In this exuberant wealth of consumer culture, it is virtually impossible to develop something like an interest in art.”

Jonas Pohler: For the cover of your books, you have1 chose a gift shop.

Barbara Straka: No, it's not a gift shop.

JP: What is that?

BS: It's not a gift shop. Please turn around. Here you can see the entire work Nietzsche Car [see the article picture] and it is an excerpt of it.

JP: Why did you choose this painting anyway?

BS: Yes, that's a teaser, a lead, an appetizer, you could say. It is found in various places. For example, in the title of the book, Nietzsche Forever? The question mark is mine, but “Nietzsche Forever” is by Thomas Hirschhorn, because it stands as a handwritten cardboard sign with three or four Nietzsche portraits on the Car. There is a red sign and asks just this question: Does this have a long-term validity? Does Nietzsche have a temporal validity and what is the future of Nietzsche's art? I would like to leave that to the observer or later art scientists.

JP: This is a car that is full of all sorts of (Nietzsche) devotional items, for example Hello Kitty2. Did you choose it because it illustrates the present tense of Nietzsche's reception so well? Very cluttered, partly commercialized, there is a lot... They also write that this Car Standstill symbolizes because the car can no longer drive.

BS: Well, you could also ask now: Why did it come to a standstill? It is overwhelmed! It is overwhelmed with kitsch and devotional items, but they are not only Nietzsche-based, but they are also — represented here by Americanized Japanese culture, namely this Hello Kitty — icon. Hello Kitty As a manga face that works with the child scheme and captivates people, has become a symbol of international pop art and pop culture, a very trivial art that depicts the infantilization of societies, popularized. I wouldn't deny that it is also art. Of course, it is also art. There are enough artists who work like this, such as Takashi Murakami, who have achieved world fame. But in this exuberant wealth of consumer culture of our time, it is virtually impossible to develop something like an interest in art. And that is also the central question that Thomas Hirschhorn asks as I understood him. In this late capitalist period, how do we manage to get back to the essential questions, sort of rummage through and then maybe get stuck with Nietzsche and actually read him again? Hirschhorn doesn't say yes that's the way it is, it's all very terrible, that is the end point and the nihilistic farewell, but he plays in the spirit...

JP: ... there is therefore positive potential!

BS: That's right, he plays the role of the observer: Get to grips with it! Read! Read it! And I think that's great. There is not only a didactic moment in it, but not in the sense of the instructive “display board aesthetics,” as artists were accused of earlier in the 1970s, but an emancipatory moment. That speaks for Hirschhorn anyway: The materials he uses are usually very simple, which anyone can buy. He has a very, how should you say, social understanding of art. He really makes art for people. And he also wants to show, in the spirit of Joseph Beuys, that basically anyone can be an artist. The materials aren't expensive, you can even buy them at a hardware store: adhesive film, wood, aluminum foil, anything — and that's his message. Nietzsche's reception is endangered today because the popularized reception, which includes all these fakes, threatens to spill it. The core icon, namely Hello Kitty, that little cat, gets Nietzsche's beard glued on. This means that amalgamation has already taken place. It's already a mutation.

JP: ... but the beard, for example, is also a memory!

2. “Texts, texts!”

BS: Nietzsche himself is very often maligned. It was a motivation on my part that I did not want to let this populist reduction stand still like this. My impression was that since the 1994 Weimar exhibition [For F. N. — Nietzsche in the visual arts of the last 30 years], in which there were many cartoons showing that Nietzsche researchers often preferred to see this funny, somewhat cute and funny Nietzsche than the serious one.3 It was my impression that this populist reception has been developing as a main strand since that time.

JP: Do you have the impression that this popularization is welcomed?

BS: Yes, it is light food.

JP: But also among researchers? Nietzsche is often portrayed as a strict philosopher, in part already a classical philosopher, and this is also how I had imagined his “admirers”, who then feel rather repulsed by this popular art.

BS: Yes, you have to make a distinction. I was talking about the classic Nietzsche researchers who spend all their time studying Nietzsche's texts. Texts, texts, texts! As late as 2000, one of the exhibition organizers in Weimar said that Nietzsche was a text. When such people see pictures of Nietzsche, they naturally want something that is a bit lighter, to relax, so to speak. In any case, this humorous confrontation with Nietzsche is a welcome opportunity to popularize. They then pick out exactly what they enjoy doing themselves. They have no questions at all for the artists, but they are looking for in art what they already know themselves. On the other hand, art historians — in such circles there is once again a distinct concept of art, which reinforces my thesis that art and philosophy simply need new levels of encounter and a new dialogue: They know too little about each other. There are worlds between the art business, the development of contemporary art, its formation of theory and classical philosophy.

JP: Why is it that interdisciplinary work between contemporary art and academic philosophy, for example, is so difficult? You write in one place:

While art historical reception up to 2000 has at least some already established artistic positions in mind, philosophical Nietzsche research remains ignorant or skeptical [...]. It is astonishing that even on the 100th anniversary of Nietzsche's death, there can be no talk of a scientific impact analysis, let alone a wider knowledge of contemporary art about Nietzsche [.] (P. 39)

At the same time, you write, there is an accusation of modern art that it is partly “indiscriminate, [and] ambivalent” (p. 40).

BS: It's not for nothing that people talk about the “art operating system.” It is a self-contained system that revolves around itself, and so is the philosophy. And once in a while, they clash with each other. There are then points of contact, so to speak, which I have now also tried to incite here, literally. But you look at yourself from a distance and, of course, only perceive excerpts. Philosophers also have a great need to catch up or catch up to do, which they may not necessarily recognize at all or of which they are not necessarily aware of. They stopped somewhere on a certain level of dealing with art. That is just not their field. In other words, the understanding of art of a classical philosopher or Nietzsche researcher cannot be expected to be on the same level as contemporary art development. That doesn't work at all. I can't blame anyone for that; they don't even have that much time. They are researchers and the artists don't have that much time either; they read this and that and then integrate it. And then there are just these occasional sparks... Of course, there are also artists who have worked with philosophers, such as Hirschhorn — and that's where it naturally becomes fruitful. That's when things get really complex. I would like to see something like that more often! That is also a suggestion, the book should be an inspiration to get into conversation with each other. But so far, it has been the case that the encounters were mostly random. One can accuse not only philosophers and Nietzsche researchers of ostracism, but also of art historians. They were traveling just as excerpts... but the so-called “gallery art” was always mostly ignored. That is just the point. And that was my catch-up project: with works by over 220 artists, I have now compiled everything that was created after 1945.

3. “Anything that now sticks to a thesis, a discipline, a conviction is out of date!”

JP: What could philosophy learn from modern art, or what do you think could result from a collaboration? You had called for exhibitions in your book, if I understood you correctly. They think that these as a format would be a good means of creating the connections mentioned above. On the other hand, I have the impression that there is still something very exclusive and limiting about them and that what is called a “cultural sector” plays a major role.

BS: First of all, it's all about opening up. It is about opening up these narrow academic limits. I don't want to get caught up in general sentences, but academic disciplines are very careful to keep their subject limits and are reluctant to go into other realms. But it is about dialogue, about an attitude that also reflects current phenomena that shape our time, society, politics and history across horizons. It is about not just looking at topics from one side, but, in Nietzsche's sense, seeing the concept of truth as something prismatic, for example. That I learn to recognize different aspects, areas, topics, simply the diversity of a phenomenon. So everything that now sticks to a thesis, to a discipline, At a conviction that is out of date! Today it is about opening up, it is about movement, it is about multidisciplinarity, it is about collaboration, it is ultimately also about the knowledge that innovation can only be created if as many different disciplines as possible work together.

JP: In the spirit of Nietzsche, actually. He has pleaded for it himself. I had the impression that you wanted to present exactly that in your book, this multifaceted diversity, which can take on very different forms.

BS: Yes, that's right. There is no one valid Nietzsche image, there is no such thing.

JP: A scientist would probably disagree with that.

BS: Yes, he would still search.

4. “It is not about monumentalizing Nietzsche — it is about very complex perspectives.”

JP: Another work from your book is by Katharina Karrenberg [see fig. 1]. I don't think this is about destruction.

BS: No, it's about development and process.

JP: I had difficulty imagining the work.

BS: Yes, I'd like to believe that.

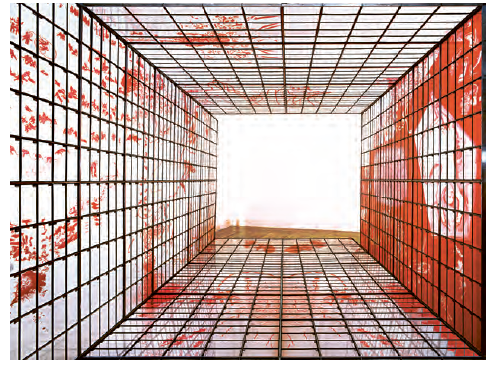

JP: How can you imagine that? Is that a room? With her? Is it in the studio, what is that?

BS: Katharina Karrenberg was invited to my exhibition for the first time Artists' metaphysics — Friedrich Nietzsche in post-modern art Participating was in Berlin in 2000. Because I knew her before, I knew that she deals extensively and explicitly with philosophy and is constantly reading, from the latest literature to non-fiction books. I invited her back then and had no idea what she was doing. She then designed an entire wall, with maybe 60 works. They're such small tablets.

JP: That was done? Or did she design them live?

BS: No, she did it at home in her studio. And then it was displayed in the exhibition room in the house on Waldsee [Berlin] on the upper floor. She was given an entire room to herself and it was about ZARA & TUSTRA. She took the character Zarathustra apart and turned it into two comic-like characters that draw on great couples in cultural history, such as Dante and Virgil or Faust and Mephisto. Two characters embarking on a journey and the artist, of course, did not even know where the journey was heading at the beginning. She first worked through the Zarathustra motif in the exhibition. Then we didn't hear from each other at all for a while and at some point I read that they had had further exhibitions and by now the whole thing had grown to over 800 pieces. Today, there are over 2000! It has become a journey through history. Follow the characters until they are resolved. At some point, the artist herself also appears. It is an immersion, a dive, an appearance, a transformation. It is very Nietzschean in the sense of this eternal movement, eternal return — the idea also comes to light, of course. In this work, she has reflected on all developments of modernism and postmodernism, including political topics, I'll give you an example: Gaza. Things are still in a state of flux. I visited them two years ago on Tempelhofer Ufer in Berlin, Kreuzberg. She lives in this work. It has become a work of art of life. But you can really imagine it that way, it's everywhere. It has developed like a stream through the entire apartment and is totally fascinating, totally fascinating! You can't even sum it up in a few words. If you go through it yourself, it's as if you're in a state of intoxication. Viewing is an exhilarating experience. The other person must then, of course, start reflecting again in order to even locate and find themselves in it. In principle, it's not finished, but she wants it now. It is basically an open work of art, in the words of Umberto Eco. An open work of art that is constantly changing, as Nietzsche said: a work of art that creates itself. In short: one of the most complex conceptual, intellectually top-class works, which stands in complete contrast to one or the other small drawing of Nietzsche, which also exists, but which can have no less intense effect. The works are all justified. This is an important aspect that I have tried to emphasize again and again: A major work can also be a small drawing. It is not about monumentality. I am bothered by the term, because it is not about monumentalizing Nietzsche — it is about very complex perspectives.

JP: You write at the beginning of your book:

[F] A cluster model was chosen to structure the subject areas, which focus on the most important works that show an iconographic development of the motif with complex references to other positions [.] (P. 5)

And at the end:

This leaves the margins of the subject groups with a grey area, or rather: a necessary blurring that is due to the complexity of art or rather owes itself to it [.] (SEE 722)

When you say there is a cluster, does that mean there is also a midpoint? This is reminiscent of Wittgenstein's family similarities or prototype semantics. There are prototypes and defining features.

BS: That is something else. So there is not one defining characteristic for me, but complexity is the criterion for the center of a cluster! It's not a guy! No, no, for God's sake! That would be a requirement again! It's about complexity and it's about incorporating so many things into a work like this one by Karrenberg! She has extensive knowledge and reflects this, so to speak, through the focus on Nietzsche in her art. But it is not a prototype! That is unique, there is no such thing again!

JP: Is that a center, can you say that, or is that also not true?

BS: Yes, but some of the chapters have two or three centers. That happens. Why — Because they also mix together. I had written that it was possible that an artist could also have been assigned to another chapter. But then I decided on one. And by that I also meant this blurring of the edges. I had to look at what the artist did on the whole, and then it emerged that I assigned him to a main theme. But with references to one or the other other topic and then I referred to that. I think that is what makes the book quite interesting from my point of view. You can leaf through, you can continue reading somewhere else and, if you are interested in this or that, you can see that there is still a connection to another chapter.

5. “... the tremendous empathy that is in there!”

JP: Instead of using the term “center,” I'll use the image of the crystal. It can be illuminated, refracted and reflected to different degrees from many sides. If we don't want to talk about the most important works now, but about these crystals... Where can we find them? You spoke of subjective and objective characteristics earlier.

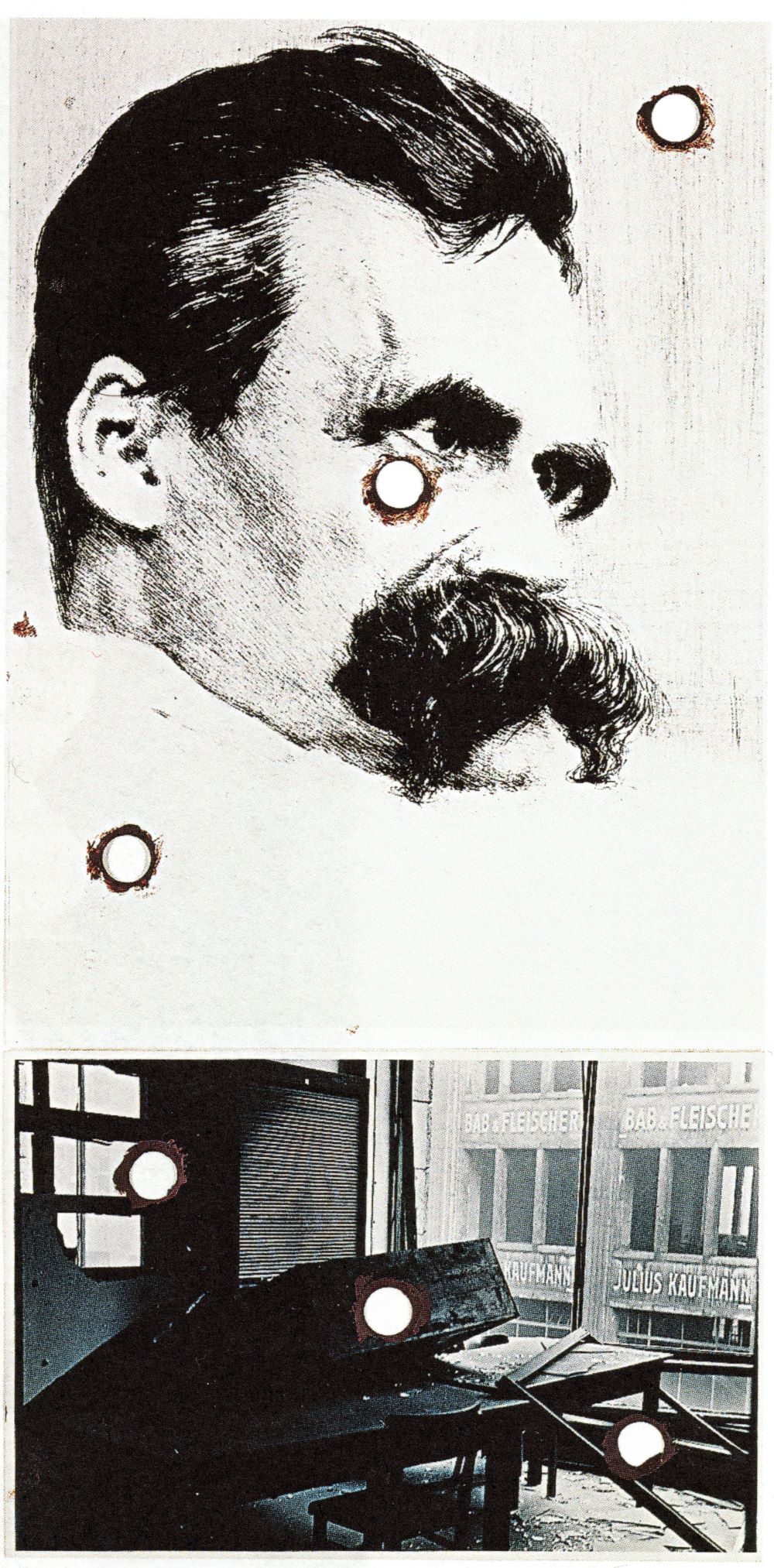

BS: Some have already been mentioned. Thomas Hirschhorn of course, Katharina Karrenberg, of course Wolf Vostell too, of course. Then Joseph Beuys, of course, Solar eclipse and corona [Figure 2]. This was a starting point for artists of his generation and the next generation to revisit Nietzsche. With Beuys, however, he still has one foot in the past. By taking up the portrait of Hans Olde — Nietzsche, who was already close to or close to death in 1899 — but turning the etching around (Olde depicted the etching backwards, there is no other way through the printing medium), Beuys Nietzsche turns back again. This means that he can be seen again at Beuys as Olde had seen and photographed him... Just a small thing, but it is important for the remark that artists were still looking for authentic Nietzsche at the beginning of the 60s and 70s. They really wanted the right Nietzsche image. They wanted to make it a topic again and were looking for the right picture. In a certain way, Beuys is already doing this small reversal. He confronts this portrait with a destroyed printing house, a devastated office that broke down in the newspaper district on Reichskristallnacht in Berlin, and opposite is a Jewish company name. You know immediately what's going on there. It is a pogrom. Wieland Schmied wrote that Beuys kept the wound painfully open. That means that at that time, the big question was whether you could even deal with Nietzsche again or whether he burned down once and for all because Nietzsche had not yet been rehabilitated back then. Beuys has nevertheless paved the way for him to be able to deal with him again and Colli and Montinari are also coming up with the critical study edition.

JP: Historically, this is certainly interesting, but I would be interested in the current period, i.e. since the 90s.

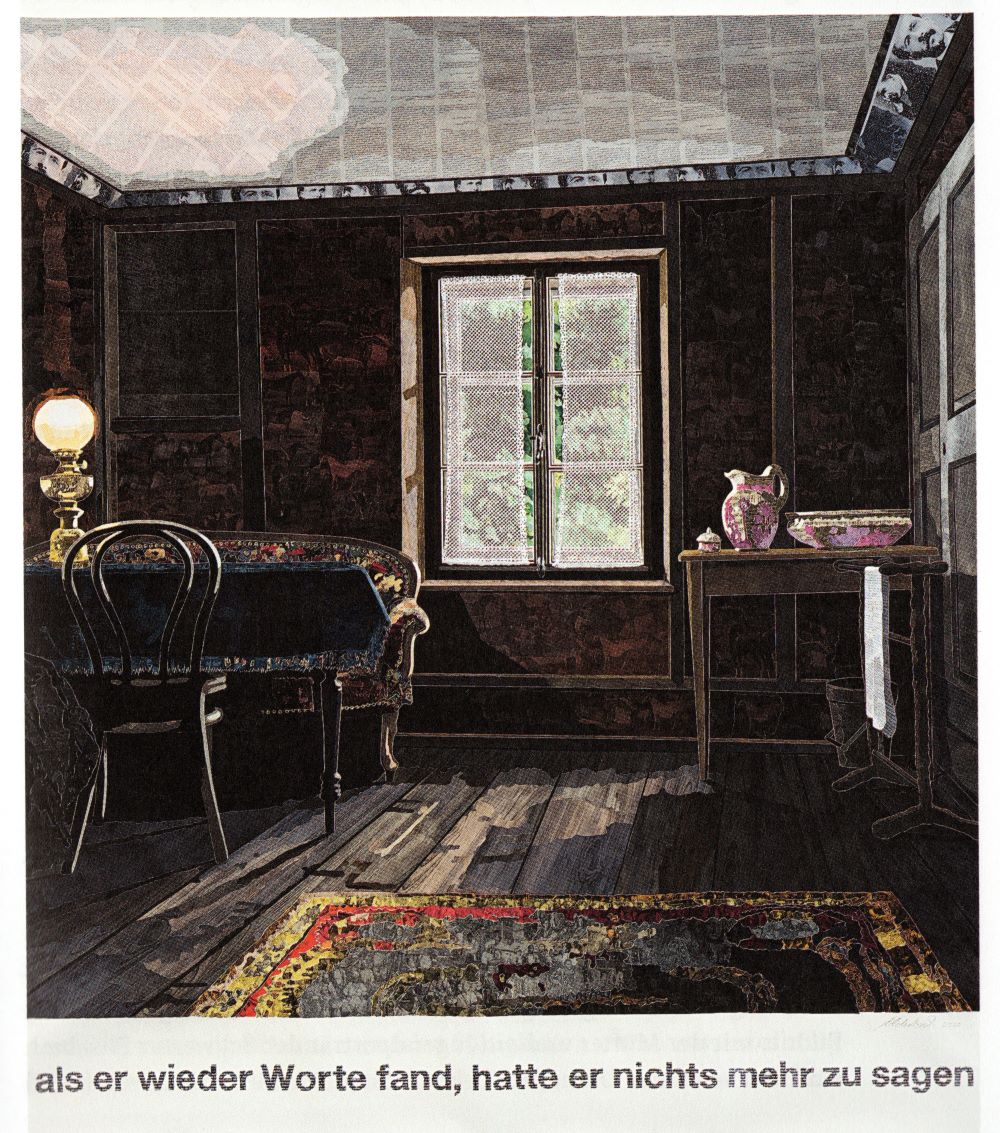

BS: I would definitely name another artist, that is Marcel Odenbach. He lived in Sils Maria during the corona period and worked in the Nietzsche room. The work is called View without God [Fig. 3] — a huge photo work that was created digitally. There you can see the Nietzsche Room as you know it... and every detail on this seemingly genuine but digital photograph is in itself a collage of other motifs. For example, Nietzsche's family, Nietzsche's letters, Nietzsche's compositions. You only see that when you stand in front of the picture. It's very big, it's full of walls. This means that, so to speak, the entire philosopher can be inferred from a single picture, and this includes this line of text: “When he found words again, he had nothing more to say.” — Of course, Nietzsche could not speak after his attack when he was in Turin, but when he found words again, he had nothing more to say. This alludes to the episode of the Turin Horse Hug.4 And now you have to imagine that the whole thing is a huge collage. It looks like a normal photo, but details are also hidden in the carpet and everywhere. There is a frieze at the top and this frieze is one portrait next to the other. Interestingly enough, there is also a fake. It's like a mosaic of Nietzsche texts, photos, trips, friends, relatives, acquaintances, Wagner... It all appears there, including the horse over and over again. I think they're all pictures of horses here on the left. So the famous episode when he supposedly hugged a horse in Turin, collapsed and then went insane.

JP: Who else should you know?

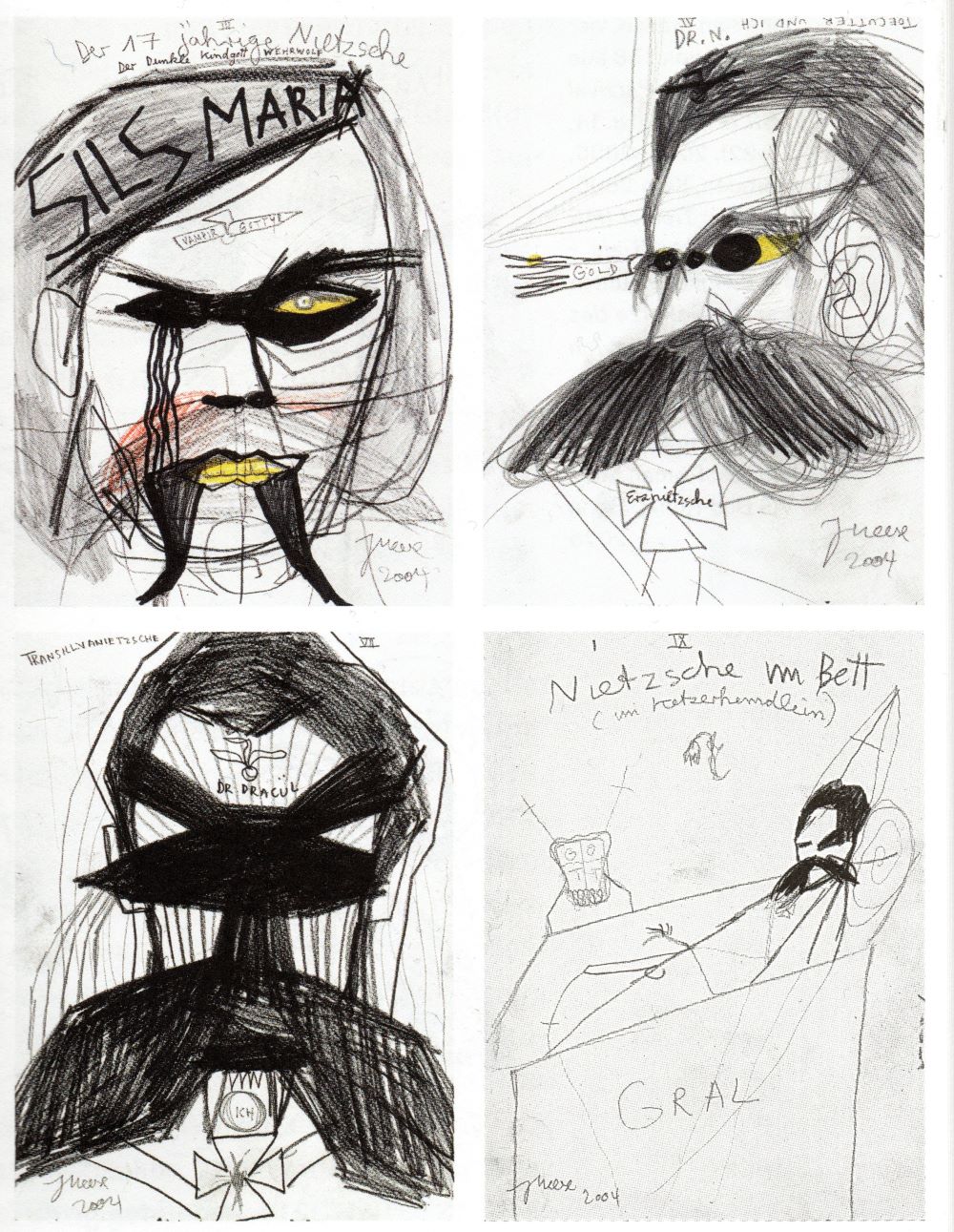

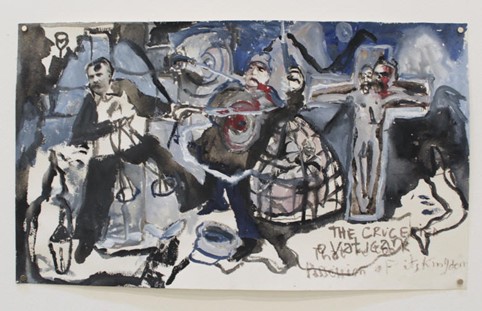

BS: It is absolutely impossible to imagine reception without Jonathan Meese [see fig. 4]. Then you should definitely know the series by Egyptian-Canadian artist Anna Boghiguian. She did a wonderful series called An Incident in the Life of a Philosopher [Figure 5]. It is only about his last days in Turin, this fateful episode, which for him ranges up to, how shall you say, metaphorical resolution of the apparitions he experienced there and which led him to write himself later in his insane letters as dionysus and The Crucified seen in a schizoid double role.

JP: What makes this work so special?

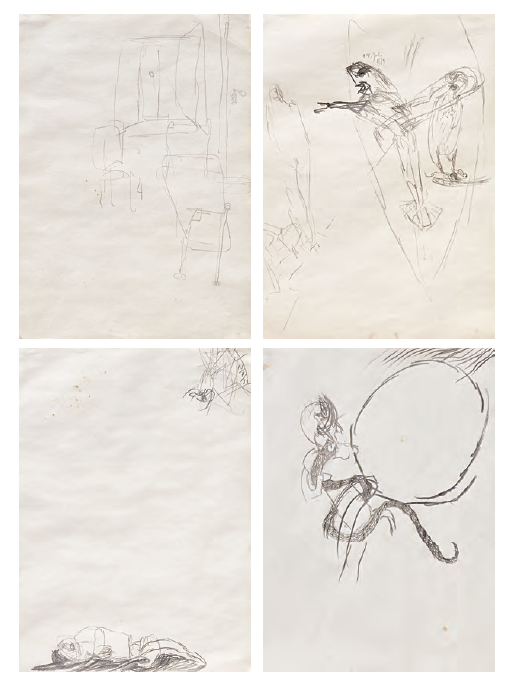

BS: ... The tremendous empathy that goes into it: on the one hand, understanding this episode, on the other hand, artistic free interpretation and how it works. She works with collage elements, some of which suggest authenticity. Then again, completely free interpretation. She virtually continues this legend. The question: How could this have happened? But then there are also flashbacks, just like in the movies. Suddenly Lou von Salomé appears and this famous Trio InfernalI always like to say, with Paul Reé. They wanted to start a residential community in Paris, but it was all very, very difficult at the time. Nietzsche had these plans, but there was a lot of jealousy and a great many misunderstandings, so that this friendship soon fell apart. But on the way to his madness, he virtually encounters this flashback again. And it represents it all. At the same time, she has written a poem in which she describes the incident as she feels about it. A great artist who has also been to the Venice Biennale. She is now an elderly woman, Anna Boghiguian, a very great artist. Then, of course, Felix Dröse, a Beuys student who made these blind drawings back in the 80s. That is in the chapter Being Nietzsche [Figure 6]. So that means how far do artists go...

JP: ... I remember an artist who put himself in Nietzsche's shoes.

BS: Right, so how far do they push this moment of identification? Of course, the question behind this is: How can I really understand Nietzsche? So not just his lyrics, but how can I understand this person in all his tragedy? How can I also understand the insane Nietzsche, who has also said interesting things from time to time, how can I understand him? And Dröse answered that for himself back in the 80s by blindfolding himself. Then the inner images that he had in his head after he had read the then newly published Nietzsche biography by Curt Paul Janz, called these three volumes before his mind's eye, so to speak, and put them on paper with blind drawings. Such intensive things were created there, totally intense pictures, which are very delicate because they are very bright pencil drawings. They are not as expressive as Meese draws them, but rather searching drawings, you could say. A searching line and yet it condenses into incredible images or even visions, where you take a keyhole perspective and look into this hospital room. Or once a figure, i.e. Nietzsche, is lying down on the ground in the hospital camp, and a black spider comes from above and approaches dangerously. This is, of course, the symbol of the mother, the spider as the mother animal, which did not let go of him until death even though she had already died in 1897. That is also a very, very big achievement, a very large series of 151 drawings.

6. “Art and philosophy are ways of ultimately reaching a life-affirming position.”

JP: At the beginning of the book and on the title, write “Nietzsche forever? “and answer the question at the end of the book with “Nietzsche forever! “, i.e. with an exclamation mark. In the book, you have already formulated the question yourself as to the future viability of this subject in contemporary art. What factors do you currently see there? What is missing now?

BS: I believe that the topic will continue to be worked on, because after the book was completed, I had found around ten new works that could be sorted into the 14 subject groups I found. One of them was about sexuality, another about what relics there are. But that would have been nothing new in that sense. So I don't think there's a whole new topic coming up now. Perhaps “Nietzsche and the natural sciences” or something like that. There is now a researcher who is investigating Nietzsche's statements about the climate, others are asking about Nietzsche's attitude towards food — this eternal search for the right diet: What is digestible for him, just as he was always looking for the right place where he could write in peace, where he could get a better grip on his headaches and eternal illness, his nausea and everything he had. It is possible that artists will pick up on this at some point. But they're not there yet... The art development or reception that artists have towards Nietzsche and biographical Nietzsche research are not on the same level. This means that if a young scientist suddenly investigates Nietzsche's statements about climate, it will take a while before they are received by artists, if they may find out by chance.

JP: Do artists work in such a way that they read for now?

BS: It can happen in multiple ways. It may be that they read Nietzsche himself, where he talks about the climate in the Upper Engadine, for example, during his travels. And if someone is now interested in science, then it may well be that he comes to it via Nietzsche himself or through scientific discussion. One example is Berlin artist Tyyne Claudia Pollmann — with these two large, very early digital works.

JP: Is that an animation?

BS: It's all computer generated. “Photobased art,” they say today — based on photographs, but everything built on a computer. Back then, in 2000, she worked with the latest American programs and is also an example of how a scientist, namely a medical doctor, deals with Nietzsche and also with the way of making digital art. So that means someone who advances into these realms and also looks at this saying by Nietzsche about art from the perspective of science and science from the perspective of art5 Take it seriously. It is a shining example of this.

JP: Can you further explain Nietzsche's future viability as a subject?

BS: This is also a central question posed by this artist, who is a professor at the Berlin-Weissensee Academy of Art. Nietzsche Bynite [Fig. 7] and Transfigure Nietzsche: It contains the term transfiguration, which of course has several anchor points in the work. (As a side note, because my book is about transfigurations). Transfigurations are changes in Nietzsche's figure through the eyes of artists. But transfiguration is also a term that Nietzsche himself uses. In the introduction, you probably mentioned his discussion with Raphael [Transfigurazione di Gesù] saw where he regarded this motif as an icon for himself.6 Transfiguration has become synonymous with Nietzsche's entire philosophy, so to speak. He sees philosophy and ultimately also art as an opportunity to affirm life on earth, human life in all its problems, ugliness, warlike, terrible forms, by, so to speak, transfiguring it. Art and philosophy are ways of ultimately reaching a life-affirming position. That is the core of Nietzschean philosophy, his philosophy of life: his affirmation of life, despite all difficulties and circumstances.

JP: Are you worried about how Nietzsche will be portrayed in art in 20 years?

BS: No, not me personally. That brings us back to the topic of the fake. I'm seeing this flood of fakes right now. There are also some artists who work with fakes, such as Michael Müller, who hosted this birthday party for Nietzsche [First and second small rehearsal for Nietzsche's birthday party 2313, 2015] has organized. A Berlin artist, also a very, very important internationally working artist. Michael Müller asks himself these questions and he actually includes fakes. I spoke to him about it: “Mr. Müller, that is fake, that is not Nietzsche-authentic.” — “Yes,” he said, “but I am interested in exactly this change, projected into the future.” He really projects this into the future and basically says: Even in 2313, Nietzsche will still keep us busy and he has organized these performances, these events, where rehearsals are taking place for these events in the distant future — the rehearsal as an artistic event. He is interested in the future of the Nietzsche painting. He is one of the few so far who virtually equates the fake with the traditional images and says: “We recognize that and you can be curious about that...” But I suspect that at some point the authentic pictures will be outnumbered, that you will have to search for them with a magnifying glass and that perhaps in 20 years the Nietzsche portrait will have completely said goodbye to the authentic philosopher. There are already plenty of examples today where he is portrayed as a bodybuilding star or something like that — he never looked like that. This is due to Pop Art; it is not interested in authentic Nietzsche. It's just not about monumentalization anymore! Today, it is about making Nietzsche human so that we can deal with him again. Away from idealization, away from monumentalization! So to speak, bring him down to the level of dialogue, meet him. There are many examples where artists literally show him as a person of today, as an athlete, as a dialogue partner, as a partygoer and tucking him into a modern outfit with sneakers on his feet or in a biker dress. You can find it good, you can laugh about it, but this level is now on! And idealization and monumentalization is the new danger of pop art, popularizing art, because that's when he becomes a superstar again. Nietzsche Superstar, Nietzsche as Superman and so on. That's all there is to be found and you have to take it with care. It goes against the direction I would like people to get away from this popular way of thinking a bit and give this issue more seriousness.

JP: Yes, I personally believe that such a middle ground is needed. On the one hand, Nietzsche must not be too exclusive, on the other hand, it must not be trivial.

BS: Contemporary works in particular are looking for new ways to prepare him for other target groups... precisely this rejuvenation that he is undergoing, this modernization and rejuvenation, which of course appeals to a new target group. I'll be completely open when he gets his old-fashioned frock coat off now.

Barbara Straka, born 1954 in Berlin, studied art education/German literature and art history/philosophy in West Berlin. As a curator and art mediator, she has initiated exhibitions and major projects of contemporary art in Germany and abroad since 1980. She was director of the 'Haus am Waldsee Berlin — Place of International Contemporary Art, 'President of the Lower Saxony Art University HBK Braunschweig and consultant for cultural and creative industries and international affairs at the Berlin Senate. She is the author and editor of numerous publications on art after 1945 (www.creartext.de).

Jonas Pohler was born in Hanover in 1995. He studied German literature in Leipzig and completed his studies with a master's degree on “Theory of Expressionism and with Franz Werfel.” He now works in Leipzig as a language teacher and is involved in integration work.

Literature

Straka, Barbara: Nietzsche Forever? Friedrich Nietzsche's Transfigurations in contemporary art. Basel: Schwabe Verlag 2025.

List of illustrations

Article image:

Thomas Hirschhorn: Nietzsche Car, 2008, mixed media, Allgarve Contemporary Art Program, Antiga Lota no Passeio Ribeirinho, Protimão, Portugal. Courtesy Jan Michalski Foundation for Writing and Literature, Montrichter (CH), photo: Romain Lopez © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 661.

Figure 1:

Katharina Karrenberg: R_A_U_S_CH_PASSAGE, interior view, 2000-2004, pigment ink, transparent paper, acrylic, bookbinding linen, aluminum, iron, L: 560 x W: 400 cm (inside: 300 cm) x H: 330 cm (inside: 300 cm) © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 490.

Figure 2:

Joseph Beuys: Solar eclipse and corona, 1978, 2-part photo collage with oil paint drawing, 37 x 18 cm, Jörg Schellmann Collection, Munich, photo: Schellmann Art © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 117.

Figure 3:

Marcel Odenbach: View without God, 2019/2021, collage, photocopies, pencil, ink on paper, 179.5 x 147.5 cm, private collection, photo: Vesko Gösel, courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne © Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 343.

Figure 4:

Jonathan Meese: Four drawings of 20 from the Nietzsche series (No. III, IV, VII, IX), 2004, felt pen, colored pencil, pencil on paper, 27.8 x 20.9 cm each, photos: Jochen Littkemann © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 149.

Figure 5:

Anna Boghiguian: A work from the series An Incident in the Life of a Philosopher, 2017, mixed media and collage © Anna Boghiguian. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 560.

Figure 6:

Felix Dröse: from the cycle Untitled (“I'm dead because I'm stupid, I am Stupid because I'm dead.”), 1981, four blind drawings of 151 (No. 21, 26, 19, 144), pencil on paper, 29.5 x 21 cm each, photos: Manos Meisen © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka: Nietzsche Forever?, P. 617.

Figure 7:

Tyyne Claudia Pollmann: Nietzsche Bynite, 2020, computer simulation, Cibachrome, 81 x 153 cm. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. In: Straka, Nietzsche Forever?, p. 396 f.

Footnotes

1: See the second part of the review by Michael Meyer-Albert (link).

2: See the corresponding illustration in the first part of the review by Michael Meyer-Albert (link).

3: Editor's note: See also the drawings by Farzane Vaziritabar on the occasion of the conference Nietzsche's Futures 2024 in Weimar (link).

4: See detailed the second part of the review by Michael Meyer-Albert.

5: Cf. The birth of tragedy, An attempt at self-criticism, 2.

6: Cf. Human, all-too-human II, The Wanderer and His Shadow, 73.