Nietzsche POParts

Aren’t words and notes

like rainbows and bridges

of semblance,

between that which is

eternally separated?

Nietzsche

POP

arts

Nietzsche

Sind

nicht

Worte

und

Töne

Regenbogen

POP

und

Scheinbrücken

zwischen

Ewig-

Geschiedenem

arts

Timely Blog on Nietzsche’s Insights

Articles

_________

Abyss and Enablement? The Suspense of Contingency

Johannes Hansmann Discusses Odo Marquard and Richard Rorty

Abyss and Enablement?

The Suspense of Contingency

Johannes Hansmann Discusses Odo Marquard and Richard Rorty

The young philosopher Johannes Hansmann has published his monograph Ironie des Schicksals im Einzelnen. Philosophie der Kontingenz bei Marquard und Rorty ("Irony and Fate in Detail. The Philosophy of Contingency in Marquard and Rorty") las year at Karl Alber. It is a remarkable study on two of the most important representatives of existential philosophy in the 20th century, the German Odo Marquard (1928-2015) and the American Richard Rorty (1931-2007). Although Nietzsche only plays a minor role, he deals with highly Nietzschean topics there, dedicates himself to the question of a successful — and for him that means in particular: authentic — life in a world after the “death of God,” to which Marquard and Rorty gave very different answers. Natalie Schulte and Paul Stephan present the book to you. A joint summary of the book's most important ideas is followed by an individual statement from each of our authors.

I. From Nietzsche via Marquard to Rorty

Hardly any thinker has shaken the intellectual topography of the 20th and 21st century as radically as Friedrich Nietzsche. With the dictum of “death of God,” he marked not only the end of an era, but the collapse of all metaphysical foundations. Where the big “absoluteness programs” break away, people are left behind in existential homelessness — an emptiness that Johannes Hansmann wrote in his book The irony of fate in detail. The philosophy of contingency in Marquard and Rorty makes it the starting point for a successful academic investigation.

Hansmann addresses the basic existential question with which Nietzsche broke up modernity and which cannot be delegated because everyone has to answer it simply by being: How do we want to live when there is no “top” anymore? It is the question of living autonomously in full awareness of both our finiteness (“vita brevis”) and the randomness of living conditions — culture, time and place — into which we are born became, and the randomness of events that still befall us will — Accidents, illnesses, losses.

Nietzsche has critiqued the supposedly eternal, immutable ideals of our culture, in both their platonic and Christian forms. He has thus deprived us of the comfort that our lives have an overriding goal and are embedded in a higher context that gives meaning to our suffering. With his book, Hansmann answers this problem. He describes what a possible life practice could look like following this criticism — and this loss of comfort. He focuses on two thinkers, Odo Marquard and Richard Rorty, who, as witty philosophers of contingency, radically address the consequences of the metaphysical homelessness of humans.

Odo Marquard (1928—2015), a formative figure in German post-war philosophy and a prominent representative of the “Knight School,” developed his ideas in response to the historical-philosophical promises of salvation of his time. As a skeptic and master of subtle irony, he pleaded for a philosophy of human finiteness that does not combat the unavailable of life, but compensates for it through serenity and adherence to tried and tested traditions.

Richard Rorty (1931—2007), one of the most influential American philosophers of the late 20th century, made the journey from an analytical language philosopher to a radical neopragmatist. He adopted the idea that philosophy could discover an “objective truth” beyond our language, and instead relied on the individual's ability to create themselves again and again through creative self-and world descriptions.

Both thinkers are heirs to Nietzsche's skepticism. After his destruction of the traditional metaphysical system of values, they are looking for new ways of thinking and living in the modern age. While Rorty Nietzsche takes up and develops his own ideas of a re-aestheticization of life freed from old burdens, Marquard creates a philosophy of contemporary serenity.

In a fruitful examination of these two approaches, Hansmann shows that the failure of supra-temporal standards does not necessarily have to result in nihilism or limitless arbitrariness. Instead, using Marquard and Rorty, he explores how the unavailable and chance can become the new center of closer reflection. He asks: Beyond the search for the one absolute, are there other paths that give us a foothold in contingency? Instead of regretting the loss of the “absolute,” we should actually welcome it, because only the absence of the absolute gives us the freedom to truly determine ourselves. As part of a philosophy of living art, Hansmann attempts to combine the strengths of Marquard and Rorty with his concept of “authentic autonomy” and to show that even without absolute criteria, the self-choice of the respective individual does not have to sink into arbitrariness.

II. How Does Hansmann Argue?

Hansmann's concise study begins with an examination of the question “What is contingency? ”. This is done primarily in terms of the conceptual history of the Ritter School, in keeping with the methodological approach of the Ritter School. Here, Hansmann creates a very interesting compilation of the (Western) philosophical debate on the topic from Aristotle to Luhmann, from which it quickly becomes clear how complex this term, which is frequently used in contemporary discussion, actually is. In the basic meaning of the term, “contingency” means that which is neither necessary nor impossible as that which is merely given in fact, which could also be different. But what exactly falls under this category and what internal distinctions does it include — particularly against the background of the theological question of how God had to create the world as he did, or not?

Hansmann's own main point here is to show that there is a small but decisive difference in meaning between the terms “contingency” and “coincidence”, which are also frequently used synonymously in philosophical discussion: They “are not the same thing, because chance loses the action-opening dimension of possibility that the contingency suits it.” (p. 21) He particularly appeals to Marquard's equation of the two terms.

According to Hansmann, contingents and random events differ not so much in their mere existence — they are equally events that neither happened necessarily nor are impossible — but in the perspective that we throw at them in our actions: On the one hand, we regard them as mere coincidences that we have to accept and which are in a certain way factually necessary, but not logically necessary; on the other hand, as opportunities for new options for action that we may or may not seize opportunities for usthat we have to relate to.

You can perhaps illustrate this distinction with the following example: I offer my son to buy him an ice cream; he can choose a type of ice cream and chooses “strawberry.” It's all completely random and I can completely accept it. But this coincidence appears as a contingency when I take my son's choice as an opportunity to ask him why he chose this kind and no other variety, what is his favorite variety in general, etc. The event therefore becomes an opportunity to improve our relationship.

For Hansmann, Marquard tends more towards the perspective of chance — which doesn't ask what new leeway random events open up, but accepts them for now — Rorty tends to the perspective of contingency, which always questions the coincidences about the new opportunities they open up.

The vast majority of the study is then carried out by reconstructing Marquard. This imbalance between the chapters is somewhat surprising, but it may be due to the fact, also marked by Hansmann (see p. 61), that there has been hardly any academic research on Marquard for many years. The philosopher worked primarily outside academia as a highly influential essayist and journalist in the late Bonn Republic, not so much within the Academy. It is therefore understandable to give a somewhat larger space to the reconstruction of Marquard's philosophy, and Hansmann actually succeeded in providing an excellent introduction here, which is worth reading for anyone who wants to learn more about Marquard's thinking.

Marquard's experimental philosophy, which has barely been recorded in monographs but primarily in lectures, essays and other brief forms, revolves around the core idea of an “apology of chance.” This means acknowledging that there is and cannot be absoluteness in the human situation simply because of the individual's mortality (“vita brevis”). We are doomed to improvise and can hardly hope to leave even a tiny footprint in the senseless course of events. Utopian hopes of all kinds — and this is where Marquard's lead against Marxism, the Frankfurt School, but also the existentialism of the French version — should be replaced by compensating stories that make us endure the senselessness of the world without ever being able to change it.

His guiding principle, also repeatedly quoted by Hansmann: “The future needs an origin.” Or even, to put the same idea in a slightly different way: The “burden of proof always lies with the person making the change” (cited on page 150). Criticism, for its part, is criticized and tried to unmask as the figment of vain narcissism by those who want to immunize themselves against any criticism, who, again in Marquard's words, not only have a conscience but want to be a conscience. Marquard therefore does not want to position himself against every change in the world, but pleads not to overwhelm the world with criticism and the urge to change, but to “spare” it.

The “liberal” philosophy of Rorty's contingency sounds completely different from this decidedly conservative approach. Despite their similar starting point — the assumption of a random or contingent world after the “death of God” — both come with diametrically opposite consequences. Rorty calls for people not to accept the world as it is, but to accept its contingency as an opportunity for individual self-creation in the sense of a Nietzschean narrative ethic of authenticity — “but we want to be the poets of our lives”1 — to understand. The “liberal ironic woman”, who behaves ironically about the world and its values, acts as the heroine of a corresponding utopia (see p. 248) — with Rorty openly saying that he does not want this to be understood as general ethics, but as an attitude that he knows can only ever be that of a small social minority.

It is therefore not surprising that Nietzsche actually plays no role in the Marquard chapter of the study, apart from a few catchphrases and allusions, while he repeatedly serves as an explicit reference figure in the Rorty chapter and also in Rorty's writings. Both are within the spiritual horizon of the modern existential philosophy founded by Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), but while Marquard is more like Kierkegaard's “ethicist,” who comes to terms with what exists and hopes to find his authenticity in it, and Heidegger's teaching of “being to death,” Rorty and Nietzsche are on the path of an, albeit a little, ethos subdued, “aesthetician.”

In his main work Either — or (1843), the Danish thinker presented the aesthetic and ethical worldview as two absolutely mutually exclusive perspectives on the world, between which the individual had to decide. This original dualism of modern existential philosophy remains unresolved even in Hansmann's study and in the end it is up to the reader himself whether Rorty's or Marquards version of it is more likely to convince him.

Kierkegaard himself followed these two “stages” of existence by a third, the religious one, in which the individual transcends both the restrictions of aesthetics and ethics by placing his existence on an absolute basis, unconditional submission to God. Following the mainstream of modern existential philosophy, this is no longer an option for Rorty and Marquard that could be seriously considered. God has just died for them in the modern age, truly died. And yet Hansmann chooses a well-known prayer of all things to outline an attempt to mediate between Rorty and Marquard at the very end of the study:

God, give me the serenity

accepting things that I can't change

the courage to change things that I can change

and the wisdom to distinguish one from the other. (P. 271)

Hansmann himself admits that this conclusion doesn't sound particularly original or profound — but it is true that philosophical insights sometimes seem quite banal once you strip them of their conceptual disguise. In any case, he is also there again with Kierkegaard, who in Sickness to death (1849) defines the communication of possibility and reality as the essential task of each individual, which existence places on him.

In his study, Hansmann thus succeeds in a contemporary continuation of existential philosophical debates in the wake of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. At a time when this way of thinking from the point of view of the individual and their life experience has tended to recede into the background in philosophy and dominate philosophies that emphasize his social integration and moral responsibility — if they do not immediately completely abstract from his existence — this is a bold undertaking. And Hansmann, not least through his pleasantly playful and unacademic language, succeeds in demonstrating that God may be dead, the “paths of freedom” that Sartre once spoke of but are therefore far from abandoning. The question of a meaningful, authentic life in a contingent world continues to haunt us, because we cannot avoid it as the mortal individuals that we are. It remains ours.

_klein.jpg)

III. Beyond Nihilism — Contingency as Freedom (Natalie Schulte)

Johannes Hansmann's research is particularly impressive due to a quality that is rare in academic writings: she speaks with her own, authentic voice. Far removed from hermetic expert discussion, Hansmann succeeds in developing a sophisticated philosophical panorama that not only informs the reader, but also touches their existentially. In doing so, he covers the spectrum — from the ancient roots of the concept of chance to the post-modern art of living — and shows that the question of contingency is the actual fate of modern people.

Hansmann establishes a distinction that is often lacking in the history of philosophy due to this clarity: contingency versus chance. While “chance” describes what unpredictably comes upon us (birth, illness, loss, death), “contingency” describes the dimension of possibility that opens up action, the knowledge that I could also act in a completely different way.

Hansmann shows in a fascinating way that this term has a specifically Christian origin: Only through the idea of Creatio ex nihilo — creation from nothing — God Could create the world had to But not — existence becomes radically contingent. After the “death of God,” this dimension of possibility is brought back into the individual by the “Creator God” projection screen. People inherit the burden and freedom of having to establish the world and themselves again and again.

In his analysis of Odo Marquard, Hansmann highlights his “Apology of Accidental” as a shield against excessive claims of absoluteness. In a world that has been disenchanted by modern science and harassed by philosophies of history (as heirs to otherworldly promises of salvation), Marquard offers “unagitated existentialism.” In contrast to the heroic pathos of Sartre, Marquard acknowledges with emphasized composure: Death is faster than the absolute choice. Hansmann makes it clear that Marquard's philosophy is not a philosophy of renunciation, but a defense of human dignity in the face of our finiteness. Since our lifetime is the “scarcest of all resources,” we cannot start from scratch every time, but must build on tried and tested traditions. Skepticism becomes a liberating attitude that frees us from the need for unity and allows us to “tell many different stories” in order to make sense of the world again.

Hansmann presents Richard Rorty as a dynamic counterpart. Here, the perspective changes from preservation to reinvention. Rorty's radical insight that truth does not exist in the world, but only in language, becomes a catalyst for the aesthetization of life. With the “liberal ironic” type, Rorty sketches an experimental figure that does justice to the contingency of existence. Being ironic means taking a stance but not being completely absorbed in it, but being able to distance yourself from it at any time and not taking yourself completely seriously in your own convictions.

The aim of Hansmann's journey is the concept of “authentic autonomy.” This is where all the threads come together: From Marquard, we learn skepticism and a productive connection to our origins; from Rorty, the courage to reconfigure the self and irony. For Hansmann, authenticity does not mean an ultimately arbitrary and therefore indifferent decision between two options, but the choice to show yourself as who you essentially are and want to be. The fact that this includes the sometimes painful discovery that being and will do not necessarily fall into one can be an occasion for a reorientation of what you want to achieve instead. Contingency is therefore not seen as a threat, but as a reason for making freedom possible. In doing so, Hansmann is making a plea for an art of living that ironically greets fate instead of despairing under it.

Interestingly enough, Nietzsche is by no means absent from this detailed analysis, although he is only mentioned in passing. The historical and philosophical forays are completely coherent and the Nietzsche-loving reader will feel Nietzsche atmospherically even far away from the “test of God.” What would Nietzsche have said about Rorty and Marquard? That can only be assumed. Even though Rorty might have impressed Nietzsche with the radicalism with which he adopted the concept of truth, the question is whether he would not have been more skeptical of the 'obscurantism, 'which Rorty knowingly or unknowingly opens the door. As far as Marquard is concerned, his orientation towards the existing would probably have been a bit too boring for him. He would probably have maintained the suspicion that it was a philosophy of “surrender.” But if Marquard wrote that only someone who can be an individual learns not to “be bribed by the applause of others,” he would certainly have regained Nietzsche's goodwill. And how could he speak out completely against someone who says about his own philosophical position: “I have no approach at all, or more correctly: I do have an approach, namely a stomach approach; but that is only a philosophical position for overreflected people” (p. 62). In conclusion, it can only be said that Hansmann has written a profound and clever book in which both thinkers, Rorty and Marquard, can shine with their exciting ideas and with their dazzling language.

IV. “Concrete Possibility” — An alternative? (Paul Stephen)

Hansmann's extremely instructive study taught me in the best sense of the word, but at the same time left me baffled. I have little to do with Marquard's conservative stance. His mantra “Future needs origin” doesn't just sound like a CDU campaign slogan. What I find particularly fascinating about Marquard's thinking is that he consistently attempts to complete a point of view that is so diametrically opposed to the mainstream of modern philosophy, yes: the modern mentality par excellence. In any case, this includes intellectual courage. And he also simply writes well (perhaps not least because he knows that he has to make his thing aesthetically appealing in order to give it the appearance of plausibility in the first place).

Rorty picks me up earlier, but at the same time, his liberal aestheticism seems to me to have lost some of its splendor. He represents more or less exactly the left-liberal image of Nietzsche, common sense-Postmodernism, with which I grew up intellectually, but which seems to me more and more like a dead end of a different kind. He simply fits in too well into a neoliberal society in which permanent creative self-invention becomes a categorical imperative and an ironic distance from everything and everyone to the Anna-normal attitude. Kierkegaard has relentlessly laid bare the aporia of aesthetic existence — Nietzsche not only glorifies them, but also uncovered their abysses. Rorty's cheerful nihilism falls behind them both.

Chance vs. contingency — this convincing conceptual distinction is taken up at the beginning of the book, but the dualism between facticity and possibility, mirrored in contrast between Marquard and Rorty, is not really conveyed at the end. You just need both. That is certainly not wrong, but it is not enough for me as a philosophical position.

One opportunity not taken by Hansmann to overcome dualism lies precisely in Aristotle's concept of possibility, with which his study begins, but only briefly touches on his decisive punchline without drawing the decisive systematic consequences from it. Hegel and in 20th century philosophy in particular the great thinker of utopian hope, Ernst Bloch (1885-1977), who crossed the line between existential philosophy and Marxism, have pointed to Aristotle's greatest philosophical innovation, arguably one of the greatest innovations in the history of philosophy of all (yes: we probably did not get much beyond him in this regard after 2,500 years): Possibility as Dýnamis or, as Bloch calls it, to determine “concrete possibility.”

In our everyday perception, we tend to regard things as coincidence in the sense of Hansmann, in their immediate circumstances. The stone is a rock, the house is a house, the plant is a plant. The Rorty consciousness of contingency is then imposed on this world of cold, immutable facts, which dissolves this facticity into nothing and, at least in imagination, out of things Anything does.

But things are never what they are. The sculptor, who created a beautiful Madonna and Child, did not simply wring off the stone something that was external to its essence. Our Lady has always slumbered in him as a concrete potential that was just waiting to be discovered and actively realized by the artist.

Generally speaking, we live in a world of fields of possibility, not facts. Every thing is a field of opportunity. Actually, there are no things. But this does not dissolve the world into a riot of arbitrariness. We are more concerned with structures that correspond to the clouds of quantum physics, whose shape is not random — the electron cannot be anywhere at any given time, that would be absurd — but also do not obey the strict requirements of classical mechanics, but are subject to certain rules of probability.

The so-called “things” are never defined in this way; they themselves refer to countless ways of “overcoming oneself” (to speak with Nietzsche). A stone is an eternal Madonna, the pillar of a palace, the flow of an ornament, provided that a knowledgeable person enters it who develops and realizes these immanent potentials. But they are therefore also not arbitrary, because the stone could never become an edible scoop of ice cream or a rain cloud in the sky. Practice would then primarily be a study of possibilities in order, through imagination and empirical research, to recognize in things at the same time what they are in their potential and then release this possibility in concrete action, provided that this possibility is in the human interest. You may not want to turn the stone into a murder weapon, at least not under most circumstances.

On the basis of the concrete sense of possibility understood in this way, a world attitude emerges beyond Marquardian resignation and Rorty's irony, which Bloch as”Docta Spes“, taught hope, or also referred to as “militant optimism.” This position is also based on the famous saying of the American theorist and activist Angela Davis (born in 1944): “I no longer accept the things I can't change. I'm changing things that I can't accept.” That's Anti-Marquard at first. I'm not coming to terms with the supposed facticities anymore, I'm looking for ways to change them. But it is also anti-Rorty, insofar as this is not about an ironic game of reinterpretations and relativizations, but the serious confrontation with things in order to change them, which requires first acknowledging and then understanding their inherent necessity in order to debunk in themselves the potential of their own self-overcoming.

Assuming, for example, inhuman situations such as slavery in the 19th century USA, Marquard's position does not appear particularly ironic, but simply cynical. Sure, he wouldn't go so far as to say that nothing should be changed at all, but he would probably be on the side of Southerners, who called for a 'slow process of reform, 'with the ulterior motive of maintaining their extra profits resulting from this extreme form of exploitation for at least a few more years longer. But why artificially maintain a state of affairs which has obviously lost all historical justification, which has actually become impossible in the name of the abstract principle “future needs origin”? Rorty, on the other hand, would probably denounce the contingency of slavery—but what exactly would his argument against Marquard actually consist of? Recognizing mere contingency is not enough; it requires an awareness of the intolerability of certain conditions and of their concrete variability.

In the case of slavery, there were, on the one hand, subjective factors — the growing resistance of slaves and whites sympathising with them, fed by the obvious complete incompatibility of this 'special institution” with the basic values of modernity and the delegimitation of racism as their pseudo-scientific justification (i.e. the recognition of the contigence of the existence of blacks as slaves) — but on the other hand, it was also objective factors that finally brought it down: It was economic It has become pointless and just an obstacle in the development of modern agriculture. Without the unwillingness to continue to accept it, it would not have been abolished any more than without the concrete window of opportunity created by industrialization and the implementation of modern institutions.

We should neither hastily accept things as factual realities nor pretend that we are acting in an unconditional field in which anything is possible. The interplay of possibility and reality is not just a matter of subjective decision, but a dialectic that takes place at every moment in things understood as a process. It is only up to us to give this process direction in our spirit.

Article Image

Paul Klee: Tightrope Walker (1923) (source)

Footnotes

Abyss and Enablement?

The Suspense of Contingency

Johannes Hansmann Discusses Odo Marquard and Richard Rorty

The young philosopher Johannes Hansmann has published his monograph Ironie des Schicksals im Einzelnen. Philosophie der Kontingenz bei Marquard und Rorty ("Irony and Fate in Detail. The Philosophy of Contingency in Marquard and Rorty") las year at Karl Alber. It is a remarkable study on two of the most important representatives of existential philosophy in the 20th century, the German Odo Marquard (1928-2015) and the American Richard Rorty (1931-2007). Although Nietzsche only plays a minor role, he deals with highly Nietzschean topics there, dedicates himself to the question of a successful — and for him that means in particular: authentic — life in a world after the “death of God,” to which Marquard and Rorty gave very different answers. Natalie Schulte and Paul Stephan present the book to you. A joint summary of the book's most important ideas is followed by an individual statement from each of our authors.

Peace from Strength

Nietzsche's Perspective on Negotiated Power and Armed Peace

Peace through Strength

Nietzsche's Perspective on Negotiated Power and Armed Peace

War in Europe was considered unthinkable for a long time — until it became a reality. But how can peace be thought of when normative guarantees fail? What if there are a few powerful and many weak players? Friedrich Nietzsche devised a surprisingly timely answer in 1879: Peace is not a sign of weakness, but an actively negotiated balance of power. He showed how a stable peace obliges all actors to build up their own strength. Nietzsche's transformation from an advocate of war to a thinker of peace based on strength is an admonition — also and especially to the weaker.

Since the Ukraine war, Europe has been operationally involved in warfare and defense. While violent wars in Western Europe were considered unlikely until a few years ago, state actors are now forced to actively intervene in what is happening. While we were pulled out of a seemingly “natural” state of peace, the idea of lasting peace only emerged in the 18th century (with Rousseau and Kant, for example) and took on increasing political and institutional shape in the 19th century.

Against this background, I would like to explain how Nietzsche explained law and justice through balances of power and how in 1879 he moved from the need for war to a perspective of lasting peace based on strength. This is illustrated by Nietzsche's example of peace among three tribes. The distinction between armed and real peace is then presented. Finally, it is explained to what extent peace, as a negotiated balance of power, requires both strong and weak actors in view of the current situation in Europe. Nietzsche's point of view is obtrusively up-to-date.1

1. Law as a Negotiated Balance of Power

Nietzsche wrote the book in 1879 during his summer stay in St. Moritz The Wanderer and His Shadow (henceforth briefly: wanderers).2 There, he is of the opinion that justice can only be achieved among equals. In the aphorism with the title”Principle of balance” it states succinctly: “Balance is the basis of justice. ”3 And a few pages later: “Right to contracts between Gleichen is based, exists as long as the power of those who have come together is equal or similar.”4. Nietzsche does not normatively justify contract law. He makes it clear that there is no metaphysical reason for law. This in turn implies that the state of nature persists even in peace, but is suppressed through the active exercise of power. In the notebook N IV 1 from 1879, this is concisely noted: “Law as long as equality of power. The state of nature doesn't stop.” (Figure 1)5 It also belongs to the”cleverness“that similarly powerful people do not get involved in senseless feuds as, that the more powerful only subdue the weaker to the extent necessary in order to save strength in turn.6 In the book of aphorisms published a year earlier Human, All Too Human Is it said in 1878 with reference to Thucydides' famous Melier Dialogue about the”The origin of justice“: “[W] o there is no clearly discernible overpower and a struggle for unsuccessful, mutual damage would arise, the idea of coming to an agreement and negotiating mutual claims. ”7 Nietzsche is not interested in the moral and legal legitimation of law, but in its concrete practical implementation. In addition, law does not reflect the physical balance of power, but only its assessment: “The right Goes originally so far, as one valuable to another, essential, invincible, invincible and the like appears. ”8 It is therefore not about objectively measurable quantities, but about a process of mutual negotiation of power. Nietzsche therefore comes to the conclusion: “Unusquisque tantum juris habet, quantum potentia valet” (in English: Everyone has as much right as they are granted in power).9 Nietzsche thus manages to avoid the normative concept of justice through the principle of balance. The lack of norms therefore does not lead to crude power politics, but to a complex and interactive process of weighing up. Volker Gerhardt sums this up aptly for Nietzsche's so-called middle creative period: “It is the insightful Power, not pure force, which creates law here. Law is the product of reciprocal estimates of power projected onto future actions. ”10

Intuitively, when you think of balance, you think of a simple scale with two weights that are compared using a uniform measure. However, Nietzsche also draws on contemporary physics — in particular thermodynamics and the balance of forces — as well as on economic models.11 Equilibrium or balance describes a relationship of forces that stabilizes as long as neither side gains the upper hand. So it is dynamic, not static. As a result, the law only applies as long as the balance of powers persists. Gerhardt writes about this: “The balances are not only those authorized in each case sides, but also the one formed by them Ganze received. Individual and whole, element and Systems can also survive under equilibrium conditions. ”12 A balance of power therefore means neither suspension of power nor powerlessness, but an intelligent, dynamic and active interplay of forces.

2. The Reassessment of War and Peace

Before 1879, the persistence of a culture in Nietzsche's writings was always linked to war. Peace only served as a transitional phase for new wars — as is often the case in his early and late works.13 Still 1878 in Human, all-too-human The idea emerged that wars could either exhaust or revive a society. The “solution” was to wage even more terrible wars. That is what the aphorism says”War is essential“:

You will find many more such surrogates of war, but perhaps through them you will see more and more that such a highly cultivized and therefore necessarily dull humanity, like that of current Europeans, requires not only wars, but also the biggest and most terrible wars — i.e. temporary relapses into barbarism — in order not to lose its culture and existence itself through the means of culture.14

The ups and downs of peace and war should lead to the continuous renewal and regeneration of culture. Only in this way could Nietzsche imagine the emergence of a higher form of culture in 1878. And yet here, with the “surrogates of war,” Nietzsche is planting the seeds for his upcoming change of opinion. In fact, violent confrontation is just one of many forms of war. Societies that have become peaceful create “surrogates,” i.e. substitute forms of war: For example, the English embark on dangerous sea voyages and adventurous expeditions.15 It is precisely this possibility of substituting military functions that allows Nietzsche to distance himself from war a good year later.

Because 1879, in wanderers, Nietzsche has fundamentally changed his position. He distances himself from the abstract idea that war is a fair competition or a cleansing conflict between two isolated opponents. The new means of Europeanization is now a peaceful democracy. The war appears superfluous, destructive and backward: “The democratic institutions are quarantine facilities against the old plague of tyrannical cravings. ”16 Nietzsche accepts democratic change and its consequences — including security, peacetime, health, human rights, mental and physical freedom, and the possibility of long-term planning. The new temporal model provides for a long-term transition through democracy to higher forms of culture. Since war only brings short-term success as a remedy, but leaves behind great destruction, Nietzsche focuses on alternative forms of war — in particular diplomacy. The “indispensable war” became an “unnecessary war” within a year.17 The transition from Human, all-too-human for wanderers It therefore does not mean a devaluation of the meaning of war, but rather a transformation of its manifestations. In wanderers War is understood as a diverse and substitutable practice.

3. Peace as a Negotiated State of Equilibrium

This change in thinking can be seen in the aphorism”The praise of the unselfish and its origin“from wanderers Understand: In a detailed example, Nietzsche describes how two enemy tribes were forced to achieve peace through the strategic intervention of a third party: “There had been strife between two neighboring chiefs for years: they devastated each other's seeds, led away armies, burned down houses, with undecided success overall because their power was pretty much equal. ”18 Violent war among equals is not worthwhile, as it causes great damage to all opponents and the benefits remain uncertain. A third tribal group was in a protected position with their possessions and was not vulnerable to both parties to the conflict. However, she threatened to side with the victim in the event of a new attack. This threat led to peace being established. In their new state of peace, all three tribes benefited from growing prosperity. Even if the third tribal group could theoretically — due to their remote geographical location — stay out of the conflict, this would reduce the prosperity and welfare of all actors. Nietzsche describes this as follows:

Everyone saw with astonishment how suddenly their prosperity and comfort grew, how they now had a dealer ready to buy and sell at the neighbor instead of a treacherous or openly mocking offender, like themselves, in unforeseen emergencies, they could pull each other out of distress instead of exploiting this neighbor's distress and increasing it to the highest level, as has happened so far, As if the human attack in both areas had improved since then: because the eyes had brightened, the foreheads were frowning, Allen was Trust in the future has become one's own — and nothing is more beneficial to people's souls and bodies than this trust.19

The prosperity and flourishing of the human community in a relationship of trust with the environment not shaken by war became “a” desirable state of affairs for Nietzsche in 1879. In addition, the embellished stroke of people, the frowned foreheads and the comforting culture of trust evokes an aesthetic of peaceful coexistence — but also an ironic exaggeration of the contemporary democratic discourse.20

Nietzsche uses the example of the three tribes to describe peace as an actively and cleverly established balance of forces. This balance is not based on normative concepts of justice and peace. Instead, peace as a state of equilibrium is based on negotiated claims to power, specifically situated actors and rational usefulness. The diplomatic negotiation of the third tribe represents a substitute form of war. The diplomats represent positions of power with regard to the desired goals and must communicate these to the other negotiating partners as convincingly as possible. In this sense, diplomacy is a higher form of war than violent conflict. However, the third tribal group also brought about this peace through threat. In the form of the threat, the war formed a diplomatic negotiation as an option. Diplomacy takes place in wanderers As a result, an important role. That is what the aphorism says”The victory of democracy“We need diplomats of the future, “who must be cultural researchers, farmers, transport experts at the same time and not have armies behind them, but reasons and benefits. ”21 Compared to his earlier writings, Nietzsche designs a more complex model of power balance, which makes different power potentials visible, taking into account the respective situation of the participating tribes. Between early writings and wanderers Democracy has changed from a tyranny of the weak to a process of negotiation charged with power.

4. Armed and Real Peace

In a striking aphorism titled”The means to real peace“Nietzsche addresses the military armies of the individual states. Although the armies would be legitimized as a means of self-defense, they implicitly reflected distrust of the other actors: “This is how all states are now opposed to each other: they presuppose the bad will of the neighbour and the good will of themselves. However, this requirement is a inhumanity, as bad and worse than war. ”22 This statement is doubly irritating: On the one hand, because it criticizes the stated dynamic balance of power as “armed peace,” and on the other hand because, depending on the point of view, it appears idealistic or naive when Nietzsche argues that the belligerent attitude can only be broken if “the” most powerful man makes himself defenseless and smashes his army:”Make yourself defenseless while being the most defensive, from a height out of the sensation — that is the means of real Peace, which must always rest on a peace of mind. ”23 First of all, this aphorism addresses an unknown future and does not describe a current possibility for Nietzsche (“And there may be a big day coming”). I interpret the aphorism as a simple continuation of the idea of peace based on strength: The most defensive, i.e. the strongest, makes himself defenseless from the position of strength.24 For Nietzsche, this is the only conceivable option for maintaining real peace: because, as explained, Nietzsche (unlike Kant) does not believe in contractual peace guarantees that exist independently of dynamic balances of power. At the same time, for Nietzsche, eternal peace cannot be established by military means, because this is the “bad attitude of the neighbor.”25 Presuppose and provoke further wars. For this reason, there could be no gradual, gradual dismantling of weapons of war to establish lasting peace. Nietzsche's reference to an almost utopian future of a peace-making advanced empire (“highest training of military order and intelligence”) testifies in particular to how implausible this fiction is.26 Seen in this light, Nietzsche's thesis is not a pacifist plea, but even an admonition: For anyone who makes himself defenseless without Having supreme power and strength weakens the dynamic balance of power.

The future peace scenario with a single main actor appears sub-complex compared to the aphorism discussed above.”The praise of the unselfish and its origin”. Instead of the dynamic complex balance of three players, each in a different location, there is a simplified view of an agonal competition with a single, peace-loving winner. In the then and today imperial order of power with several major powers, it is difficult to imagine that there would once be a single “most defensive” or in the singular “a people” who could destroy their military means. In addition, this prospect of peace without alternative omits the manifold benefits of peaceful coexistence, as exemplified by the three tribes. The latter led to “trust in the future”27, which has great potential for peacemaking.

5. Conclusion: Peace through Strength Obliges All Actors

Although the 19th century in Europe was marked by wars, it was comparatively a “period of low violence. ”28 This left room for new ideas of peace. Nietzsche, who worked briefly as a medic during the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, seemed mentally distant enough in 1879 to attest to the violent wars had mostly destructive consequences. At the same time, his experiences of war made him firstly immune from falling into naive pacifism and secondly too familiar with realpolitik to believe in a universalist contract theory. Historiography thus left little hope for the enforceability of a philosophical legitimation of law. Nietzsche invites you to look at current challenges from a sober perspective of power politics and not to prematurely dismiss them as mere acts of violence. Because Nietzsche's reassessment of peace and democracy in wanderers is a plea for an intelligent, power-conscious peace order. Peace is not a sign of exhaustion, weakness or retreat, as in earlier works, but the conscious negotiation and balancing of a dynamic balance. Peace is an active state that binds and rearranges forces — not the absence of power. Peace is therefore also not a passive result of determined power relations. Peace as a dynamic balance of power is a cultural development effort: The notes from 1879 state: “The fact that there is an equilibrium is a big step” (Figure 2).29 As Henning Ottmann put it, this is a “philosophy of peace,” whose “condition [...] is strength.”30 In this view, there are no normative guarantees that stand the test of time far away from situateness, usefulness and claims to power.

There is (unfortunately) a lot to learn from this today. Because especially in a time of strengthened (or made visible) power politics, eroding multilateral institutions and threatening nuclear scenes, Nietzsche's perspective is remarkable: In the spirit of Nietzsche, the question today is which diplomatic negotiations can lead to new, stabilizing balances of power by individual actors beyond normative values? What could a useful peace look like for all actors? When it comes to peace, how can all actors actively manage their power (as opposed to relinquishing power)? This is because weaker actors cannot evade responsibility by pointing out their weakness or pacifism, because stabilizing effects must be negotiated even in the modalities of subjugation. This awareness of power and vulnerability is important when negotiating with actors who threaten to resort to military means (and with those who do not follow the rules negotiated with substitute means). A balance in relation to all stabilizing forces obliges all actors to their own strength. In times of armed peace and increasing armament, this cannot only be achieved through diplomatic skill, but must also be supported by economic and military strength. In this systemic view, chaos breaks out not only because of the misconduct of individual actors, but because the state of equilibrium sustained by all became unstable from several sides. This is how we are dealing today with the opposite starting point of Nietzsche's fiction: The most defensive are making themselves even more defensive, which is why armed peace continues to represent the only balance that can be achieved. And this obliges all actors to active power politics and strength. This is in line with Europe's current situation at a time when rules only apply “as long as an authority is prepared to enforce them. ”31

Tobias Brücker has a doctorate in cultural studies and is head of HR personnel development at the Zurich University of the Arts. He has researched Nietzsche's working methods and published the monograph in 2019 On the road to philosophy. Friedrich Nietzsche writes “The Wanderer and His Shadow” published. He is interested in all facets of diets, authorship, and creativity techniques in philosophy and the arts.

Article Image

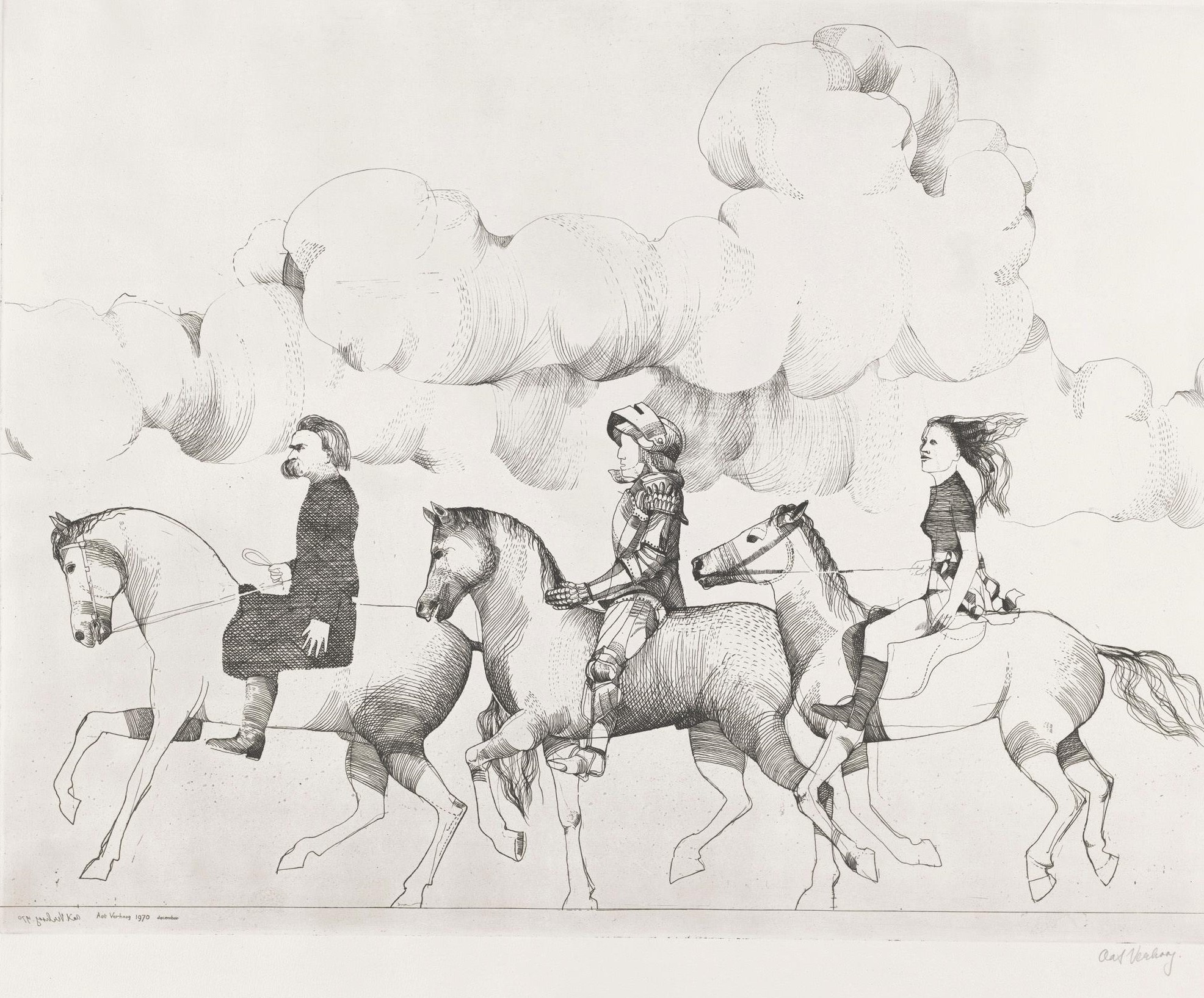

L'Equilibre Européen (“The European Balance”) is a famous lithograph by French cartoonist Honoré Daumier (1808—1879). It was published in 1866 in the satirical magazine Le Charivari published — during a period of great European tensions, just before and around the Prussian-Austrian War (spring).

Literature

Brücker, Tobias: On the road to philosophy. Friedrich Nietzsche writes “The Wanderer and His Shadow”. Paderborn 2019 (link).

Gerhardt, Volker: The “principle of balance.” On the relationship between law and power in Nietzsche. In: Nietzsche studies 12 (1983), PP. 111-133.

Kaufmann, Sebastian: Commentary on Nietzsche's “The Wanderer and His Shadow”. Berlin & Boston 2024.

Münkler, Herfried: The old world order is broken. In: NZZ, 2.7.2025, p. 32.

Osterhammel, Jürgen: The transformation of the world. A story of the 19th century. Munich 2009.

Ottmann, Henning: Philosophy and politics in Nietzsche. Berlin & New York 1999.

Footnotes

1: This article is based on a talk titled “La paix: un état de la puissance dans Le Voyageur et son ombre“, which I held at the following meeting: “Les figures de la puissance chez Nietzsche”, Journée d'études Nietzschéennes à l'Ens, École normale supérieure de Paris, 29.03.2018.

2: As an attachment to Human, all-too-human Considered, this work has so far received little importance. A detailed study of the history of editions and the topic of democracy can be found in: Tobias Brücker, On the road to philosophy, P. 197-239.

3: The Wanderer and His Shadow (in the following: WS), 22.

4: WS 26.

6: Cf. WS 26.

7: Human, all-too-human Vol. 1, 92.

8: Human, all-too-human Vol. 1, 93.

9: Ibid.

10: Cf. Volker Gerhardt, The “principle of balance”, P. 127.

11: Cf. Gerhardt, The “principle of balance”.

12: Ibid., p. 129.

13: See e.g. CV3, MAI I, 477, MA I, 444, JGB 210, JGB 238, NF 1888, 14 [192]. See also Brücker, On the way, P. 201-207.

14: Human, all-too-human Vol. 1, 477.

15: See ibid. 1

16: WS 289.

17: See in detail: Brücker, On the way, P. 197-239.

18: WS 190.

19: Ibid.

20: Cf. Brücker, On the way, p. 209 ff.

21: WS 292.

22: WS 284.

23: Ibid.

24: The commentary on WS includes various interpretations, see Sebastian Kaufmann, remark, P. 485-489.

25: WS 284.

26: See also here the remarks on the function of rhetoric and the undetermined future in Nietzsche's aphorisms of democracy in Brücker, On the way, p. 209 f.

27: WS 190.

28: Jürgen Osterhammel: The transformation of the world, P. 705.

29: Notebook N IV 1, p. 3. On pages 2 and 3, there are notes which serve as precursors to the quoted aphorism WS 22”Principle of balance“were processed.

30: Henning Ottmann, Philosophy and politics in Nietzsche, p. 127.m

31: Herfried Münkler, The old world order is broken.

Peace through Strength

Nietzsche's Perspective on Negotiated Power and Armed Peace

War in Europe was considered unthinkable for a long time — until it became a reality. But how can peace be thought of when normative guarantees fail? What if there are a few powerful and many weak players? Friedrich Nietzsche devised a surprisingly timely answer in 1879: Peace is not a sign of weakness, but an actively negotiated balance of power. He showed how a stable peace obliges all actors to build up their own strength. Nietzsche's transformation from an advocate of war to a thinker of peace based on strength is an admonition — also and especially to the weaker.

Discussion with Barbara Straka

Interview with Barbara Straka about Her Book Nietzsche Forever?

“It is no longer about monumentalization! Artists today want to make Nietzsche human so that one can deal with him in a new way.”

Interview with Barbara Straka about Her Book Nietzsche Forever?

Last year, curator and art historian Barbara Straka published a two-volume monograph entitled Nietzsche forever? Friedrich Nietzsches Transfigurationen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst (Nietzsche Forever? Friedrich Nietzsche's Transfigurations in Contemporary Art), in which she explains Nietzsche's significance for the visual arts of the present day. After Michael Meyer-Albert dedicated a two-part review to her work in recent weeks (part 1, part 2), here follows an interview conducted by our author Jonas Pohler with the author in Potsdam. He discussed her book with her, but also about the not always easy relationship between philosophy and contemporary art.

1. “In this exuberant wealth of consumer culture, it is virtually impossible to develop something like an interest in art.”

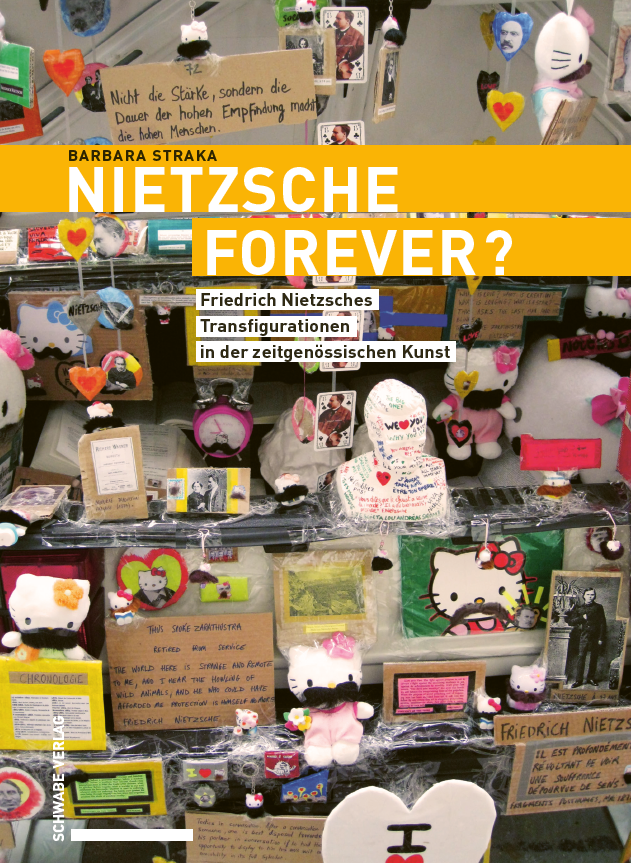

Jonas Pohler: For the cover of your books, you have1 chose a gift shop.

Barbara Straka: No, it's not a gift shop.

JP: What is that?

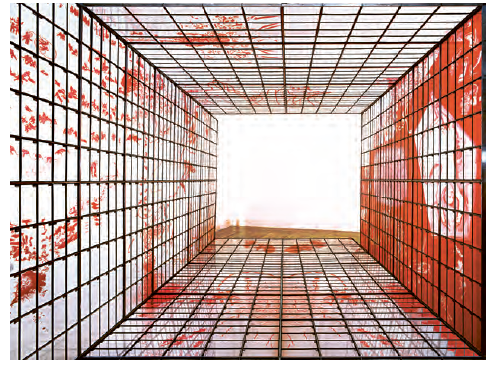

BS: It's not a gift shop. Please turn around. Here you can see the entire work Nietzsche Car [see the article picture] and it is an excerpt of it.

JP: Why did you choose this painting anyway?

BS: Yes, that's a teaser, a lead, an appetizer, you could say. It is found in various places. For example, in the title of the book, Nietzsche Forever? The question mark is mine, but “Nietzsche Forever” is by Thomas Hirschhorn, because it stands as a handwritten cardboard sign with three or four Nietzsche portraits on the Car. There is a red sign and asks just this question: Does this have a long-term validity? Does Nietzsche have a temporal validity and what is the future of Nietzsche's art? I would like to leave that to the observer or later art scientists.

JP: This is a car that is full of all sorts of (Nietzsche) devotional items, for example Hello Kitty2. Did you choose it because it illustrates the present tense of Nietzsche's reception so well? Very cluttered, partly commercialized, there is a lot... They also write that this Car Standstill symbolizes because the car can no longer drive.

BS: Well, you could also ask now: Why did it come to a standstill? It is overwhelmed! It is overwhelmed with kitsch and devotional items, but they are not only Nietzsche-based, but they are also — represented here by Americanized Japanese culture, namely this Hello Kitty — icon. Hello Kitty As a manga face that works with the child scheme and captivates people, has become a symbol of international pop art and pop culture, a very trivial art that depicts the infantilization of societies, popularized. I wouldn't deny that it is also art. Of course, it is also art. There are enough artists who work like this, such as Takashi Murakami, who have achieved world fame. But in this exuberant wealth of consumer culture of our time, it is virtually impossible to develop something like an interest in art. And that is also the central question that Thomas Hirschhorn asks as I understood him. In this late capitalist period, how do we manage to get back to the essential questions, sort of rummage through and then maybe get stuck with Nietzsche and actually read him again? Hirschhorn doesn't say yes that's the way it is, it's all very terrible, that is the end point and the nihilistic farewell, but he plays in the spirit...

JP: ... there is therefore positive potential!

BS: That's right, he plays the role of the observer: Get to grips with it! Read! Read it! And I think that's great. There is not only a didactic moment in it, but not in the sense of the instructive “display board aesthetics,” as artists were accused of earlier in the 1970s, but an emancipatory moment. That speaks for Hirschhorn anyway: The materials he uses are usually very simple, which anyone can buy. He has a very, how should you say, social understanding of art. He really makes art for people. And he also wants to show, in the spirit of Joseph Beuys, that basically anyone can be an artist. The materials aren't expensive, you can even buy them at a hardware store: adhesive film, wood, aluminum foil, anything — and that's his message. Nietzsche's reception is endangered today because the popularized reception, which includes all these fakes, threatens to spill it. The core icon, namely Hello Kitty, that little cat, gets Nietzsche's beard glued on. This means that amalgamation has already taken place. It's already a mutation.

JP: ... but the beard, for example, is also a memory!

2. “Texts, texts!”

BS: Nietzsche himself is very often maligned. It was a motivation on my part that I did not want to let this populist reduction stand still like this. My impression was that since the 1994 Weimar exhibition [For F. N. — Nietzsche in the visual arts of the last 30 years], in which there were many cartoons showing that Nietzsche researchers often preferred to see this funny, somewhat cute and funny Nietzsche than the serious one.3 It was my impression that this populist reception has been developing as a main strand since that time.

JP: Do you have the impression that this popularization is welcomed?

BS: Yes, it is light food.

JP: But also among researchers? Nietzsche is often portrayed as a strict philosopher, in part already a classical philosopher, and this is also how I had imagined his “admirers”, who then feel rather repulsed by this popular art.

BS: Yes, you have to make a distinction. I was talking about the classic Nietzsche researchers who spend all their time studying Nietzsche's texts. Texts, texts, texts! As late as 2000, one of the exhibition organizers in Weimar said that Nietzsche was a text. When such people see pictures of Nietzsche, they naturally want something that is a bit lighter, to relax, so to speak. In any case, this humorous confrontation with Nietzsche is a welcome opportunity to popularize. They then pick out exactly what they enjoy doing themselves. They have no questions at all for the artists, but they are looking for in art what they already know themselves. On the other hand, art historians — in such circles there is once again a distinct concept of art, which reinforces my thesis that art and philosophy simply need new levels of encounter and a new dialogue: They know too little about each other. There are worlds between the art business, the development of contemporary art, its formation of theory and classical philosophy.

JP: Why is it that interdisciplinary work between contemporary art and academic philosophy, for example, is so difficult? You write in one place:

While art historical reception up to 2000 has at least some already established artistic positions in mind, philosophical Nietzsche research remains ignorant or skeptical [...]. It is astonishing that even on the 100th anniversary of Nietzsche's death, there can be no talk of a scientific impact analysis, let alone a wider knowledge of contemporary art about Nietzsche [.] (P. 39)

At the same time, you write, there is an accusation of modern art that it is partly “indiscriminate, [and] ambivalent” (p. 40).

BS: It's not for nothing that people talk about the “art operating system.” It is a self-contained system that revolves around itself, and so is the philosophy. And once in a while, they clash with each other. There are then points of contact, so to speak, which I have now also tried to incite here, literally. But you look at yourself from a distance and, of course, only perceive excerpts. Philosophers also have a great need to catch up or catch up to do, which they may not necessarily recognize at all or of which they are not necessarily aware of. They stopped somewhere on a certain level of dealing with art. That is just not their field. In other words, the understanding of art of a classical philosopher or Nietzsche researcher cannot be expected to be on the same level as contemporary art development. That doesn't work at all. I can't blame anyone for that; they don't even have that much time. They are researchers and the artists don't have that much time either; they read this and that and then integrate it. And then there are just these occasional sparks... Of course, there are also artists who have worked with philosophers, such as Hirschhorn — and that's where it naturally becomes fruitful. That's when things get really complex. I would like to see something like that more often! That is also a suggestion, the book should be an inspiration to get into conversation with each other. But so far, it has been the case that the encounters were mostly random. One can accuse not only philosophers and Nietzsche researchers of ostracism, but also of art historians. They were traveling just as excerpts... but the so-called “gallery art” was always mostly ignored. That is just the point. And that was my catch-up project: with works by over 220 artists, I have now compiled everything that was created after 1945.

3. “Anything that now sticks to a thesis, a discipline, a conviction is out of date!”

JP: What could philosophy learn from modern art, or what do you think could result from a collaboration? You had called for exhibitions in your book, if I understood you correctly. They think that these as a format would be a good means of creating the connections mentioned above. On the other hand, I have the impression that there is still something very exclusive and limiting about them and that what is called a “cultural sector” plays a major role.

BS: First of all, it's all about opening up. It is about opening up these narrow academic limits. I don't want to get caught up in general sentences, but academic disciplines are very careful to keep their subject limits and are reluctant to go into other realms. But it is about dialogue, about an attitude that also reflects current phenomena that shape our time, society, politics and history across horizons. It is about not just looking at topics from one side, but, in Nietzsche's sense, seeing the concept of truth as something prismatic, for example. That I learn to recognize different aspects, areas, topics, simply the diversity of a phenomenon. So everything that now sticks to a thesis, to a discipline, At a conviction that is out of date! Today it is about opening up, it is about movement, it is about multidisciplinarity, it is about collaboration, it is ultimately also about the knowledge that innovation can only be created if as many different disciplines as possible work together.

JP: In the spirit of Nietzsche, actually. He has pleaded for it himself. I had the impression that you wanted to present exactly that in your book, this multifaceted diversity, which can take on very different forms.

BS: Yes, that's right. There is no one valid Nietzsche image, there is no such thing.

JP: A scientist would probably disagree with that.

BS: Yes, he would still search.

4. “It is not about monumentalizing Nietzsche — it is about very complex perspectives.”

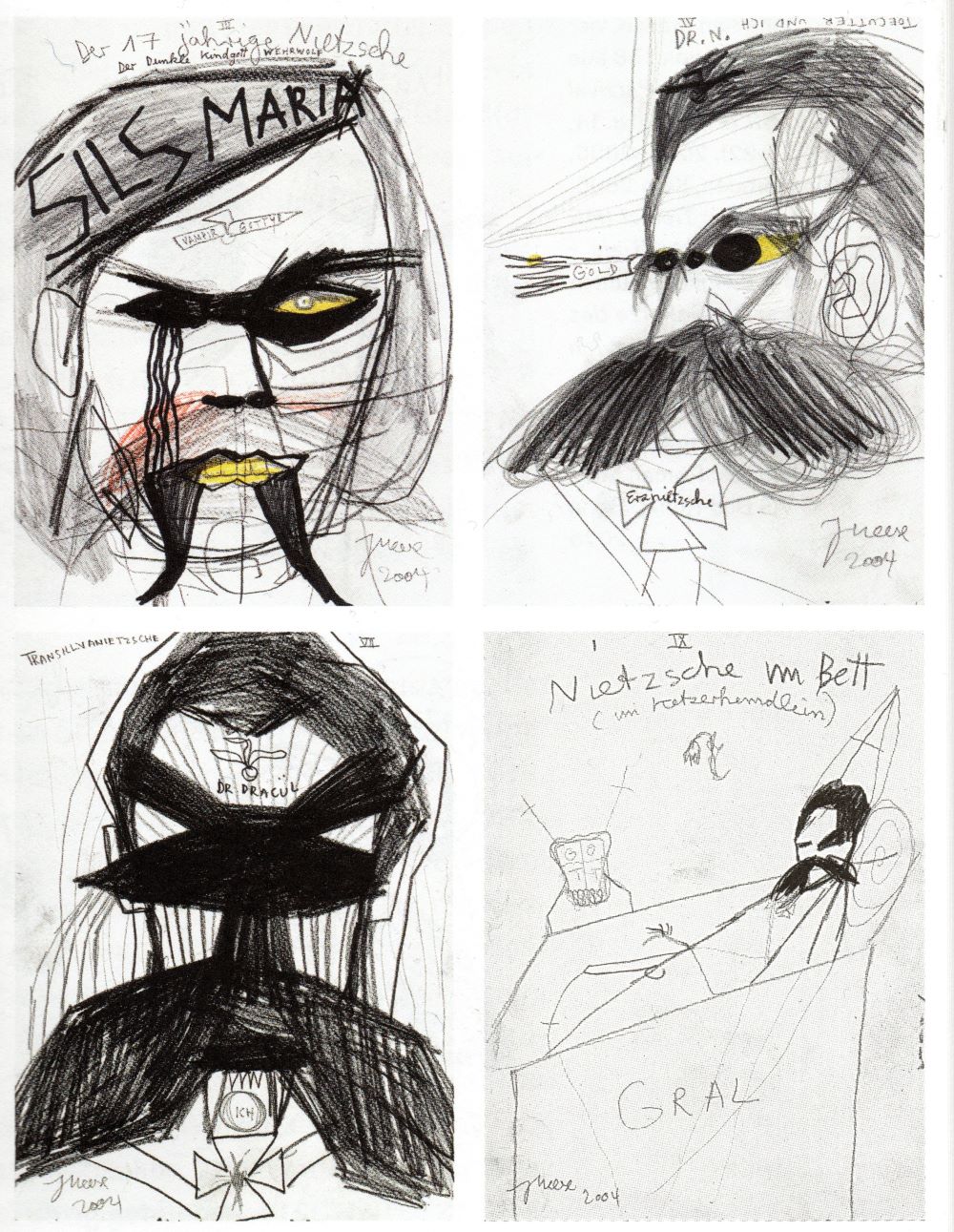

JP: Another work from your book is by Katharina Karrenberg [see fig. 1]. I don't think this is about destruction.

BS: No, it's about development and process.

JP: I had difficulty imagining the work.

BS: Yes, I'd like to believe that.

JP: How can you imagine that? Is that a room? With her? Is it in the studio, what is that?

BS: Katharina Karrenberg was invited to my exhibition for the first time Artists' metaphysics — Friedrich Nietzsche in post-modern art Participating was in Berlin in 2000. Because I knew her before, I knew that she deals extensively and explicitly with philosophy and is constantly reading, from the latest literature to non-fiction books. I invited her back then and had no idea what she was doing. She then designed an entire wall, with maybe 60 works. They're such small tablets.

JP: That was done? Or did she design them live?

BS: No, she did it at home in her studio. And then it was displayed in the exhibition room in the house on Waldsee [Berlin] on the upper floor. She was given an entire room to herself and it was about ZARA & TUSTRA. She took the character Zarathustra apart and turned it into two comic-like characters that draw on great couples in cultural history, such as Dante and Virgil or Faust and Mephisto. Two characters embarking on a journey and the artist, of course, did not even know where the journey was heading at the beginning. She first worked through the Zarathustra motif in the exhibition. Then we didn't hear from each other at all for a while and at some point I read that they had had further exhibitions and by now the whole thing had grown to over 800 pieces. Today, there are over 2000! It has become a journey through history. Follow the characters until they are resolved. At some point, the artist herself also appears. It is an immersion, a dive, an appearance, a transformation. It is very Nietzschean in the sense of this eternal movement, eternal return — the idea also comes to light, of course. In this work, she has reflected on all developments of modernism and postmodernism, including political topics, I'll give you an example: Gaza. Things are still in a state of flux. I visited them two years ago on Tempelhofer Ufer in Berlin, Kreuzberg. She lives in this work. It has become a work of art of life. But you can really imagine it that way, it's everywhere. It has developed like a stream through the entire apartment and is totally fascinating, totally fascinating! You can't even sum it up in a few words. If you go through it yourself, it's as if you're in a state of intoxication. Viewing is an exhilarating experience. The other person must then, of course, start reflecting again in order to even locate and find themselves in it. In principle, it's not finished, but she wants it now. It is basically an open work of art, in the words of Umberto Eco. An open work of art that is constantly changing, as Nietzsche said: a work of art that creates itself. In short: one of the most complex conceptual, intellectually top-class works, which stands in complete contrast to one or the other small drawing of Nietzsche, which also exists, but which can have no less intense effect. The works are all justified. This is an important aspect that I have tried to emphasize again and again: A major work can also be a small drawing. It is not about monumentality. I am bothered by the term, because it is not about monumentalizing Nietzsche — it is about very complex perspectives.

JP: You write at the beginning of your book:

[F] A cluster model was chosen to structure the subject areas, which focus on the most important works that show an iconographic development of the motif with complex references to other positions [.] (P. 5)

And at the end:

This leaves the margins of the subject groups with a grey area, or rather: a necessary blurring that is due to the complexity of art or rather owes itself to it [.] (SEE 722)

When you say there is a cluster, does that mean there is also a midpoint? This is reminiscent of Wittgenstein's family similarities or prototype semantics. There are prototypes and defining features.

BS: That is something else. So there is not one defining characteristic for me, but complexity is the criterion for the center of a cluster! It's not a guy! No, no, for God's sake! That would be a requirement again! It's about complexity and it's about incorporating so many things into a work like this one by Karrenberg! She has extensive knowledge and reflects this, so to speak, through the focus on Nietzsche in her art. But it is not a prototype! That is unique, there is no such thing again!

JP: Is that a center, can you say that, or is that also not true?

BS: Yes, but some of the chapters have two or three centers. That happens. Why — Because they also mix together. I had written that it was possible that an artist could also have been assigned to another chapter. But then I decided on one. And by that I also meant this blurring of the edges. I had to look at what the artist did on the whole, and then it emerged that I assigned him to a main theme. But with references to one or the other other topic and then I referred to that. I think that is what makes the book quite interesting from my point of view. You can leaf through, you can continue reading somewhere else and, if you are interested in this or that, you can see that there is still a connection to another chapter.

5. “... the tremendous empathy that is in there!”

JP: Instead of using the term “center,” I'll use the image of the crystal. It can be illuminated, refracted and reflected to different degrees from many sides. If we don't want to talk about the most important works now, but about these crystals... Where can we find them? You spoke of subjective and objective characteristics earlier.

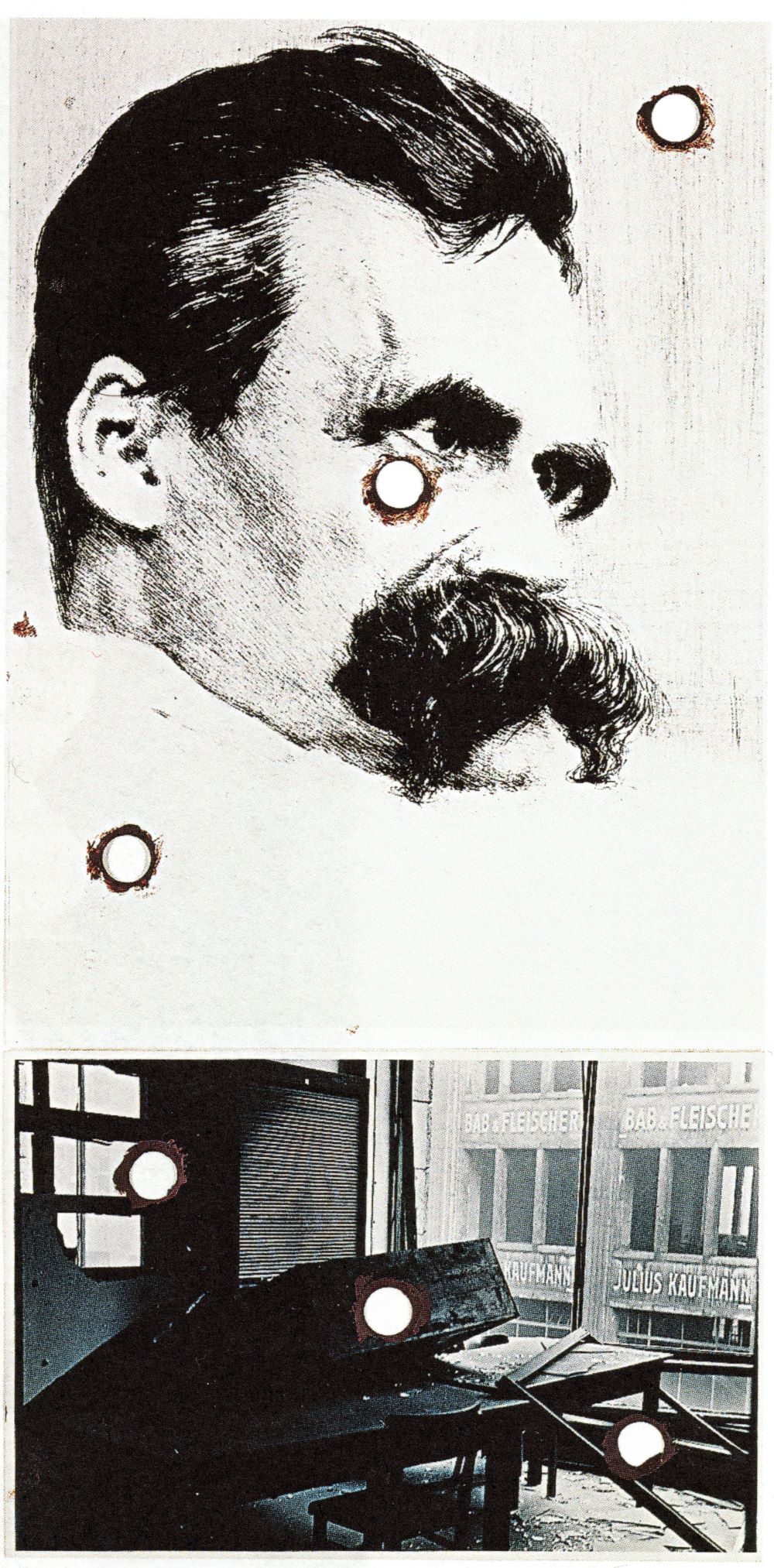

BS: Some have already been mentioned. Thomas Hirschhorn of course, Katharina Karrenberg, of course Wolf Vostell too, of course. Then Joseph Beuys, of course, Solar eclipse and corona [Figure 2]. This was a starting point for artists of his generation and the next generation to revisit Nietzsche. With Beuys, however, he still has one foot in the past. By taking up the portrait of Hans Olde — Nietzsche, who was already close to or close to death in 1899 — but turning the etching around (Olde depicted the etching backwards, there is no other way through the printing medium), Beuys Nietzsche turns back again. This means that he can be seen again at Beuys as Olde had seen and photographed him... Just a small thing, but it is important for the remark that artists were still looking for authentic Nietzsche at the beginning of the 60s and 70s. They really wanted the right Nietzsche image. They wanted to make it a topic again and were looking for the right picture. In a certain way, Beuys is already doing this small reversal. He confronts this portrait with a destroyed printing house, a devastated office that broke down in the newspaper district on Reichskristallnacht in Berlin, and opposite is a Jewish company name. You know immediately what's going on there. It is a pogrom. Wieland Schmied wrote that Beuys kept the wound painfully open. That means that at that time, the big question was whether you could even deal with Nietzsche again or whether he burned down once and for all because Nietzsche had not yet been rehabilitated back then. Beuys has nevertheless paved the way for him to be able to deal with him again and Colli and Montinari are also coming up with the critical study edition.

JP: Historically, this is certainly interesting, but I would be interested in the current period, i.e. since the 90s.

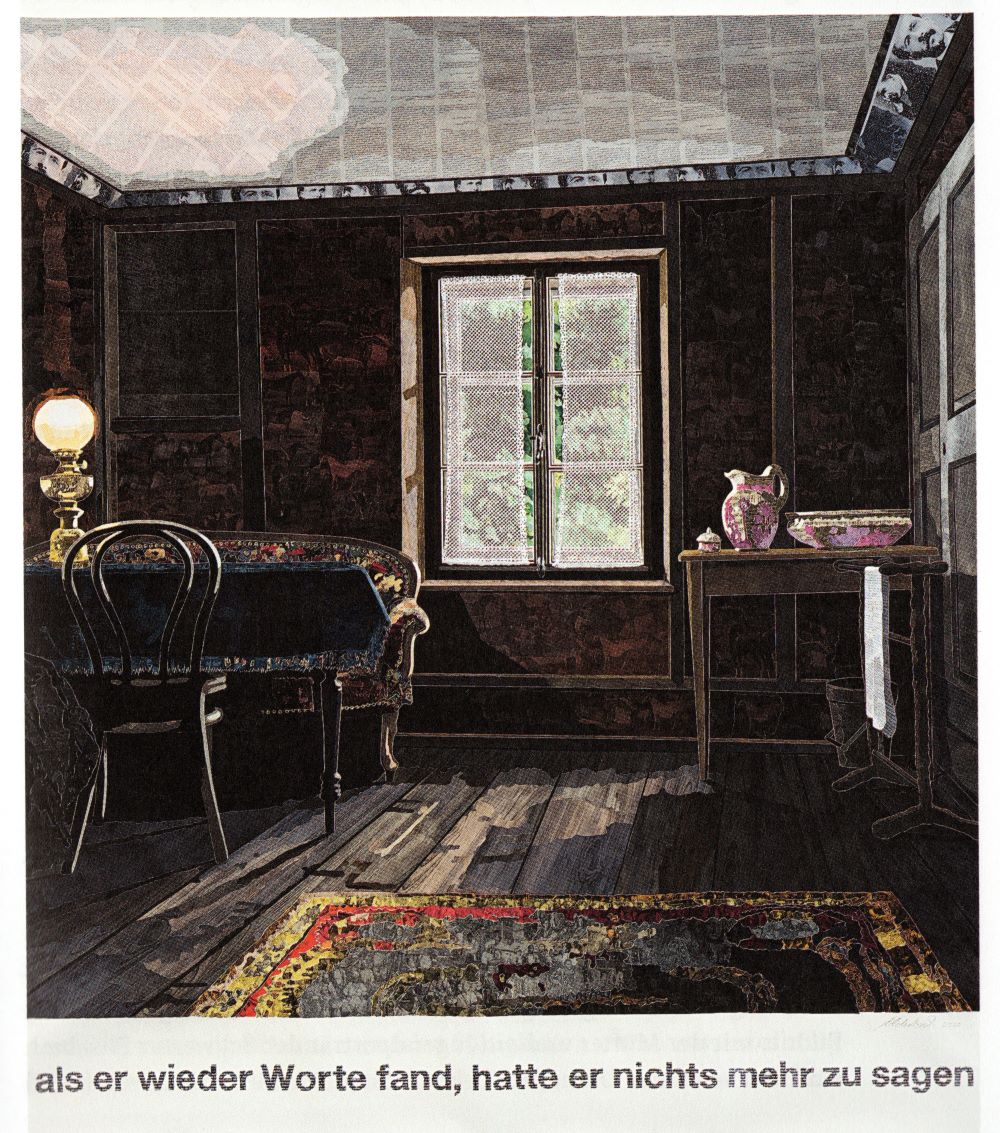

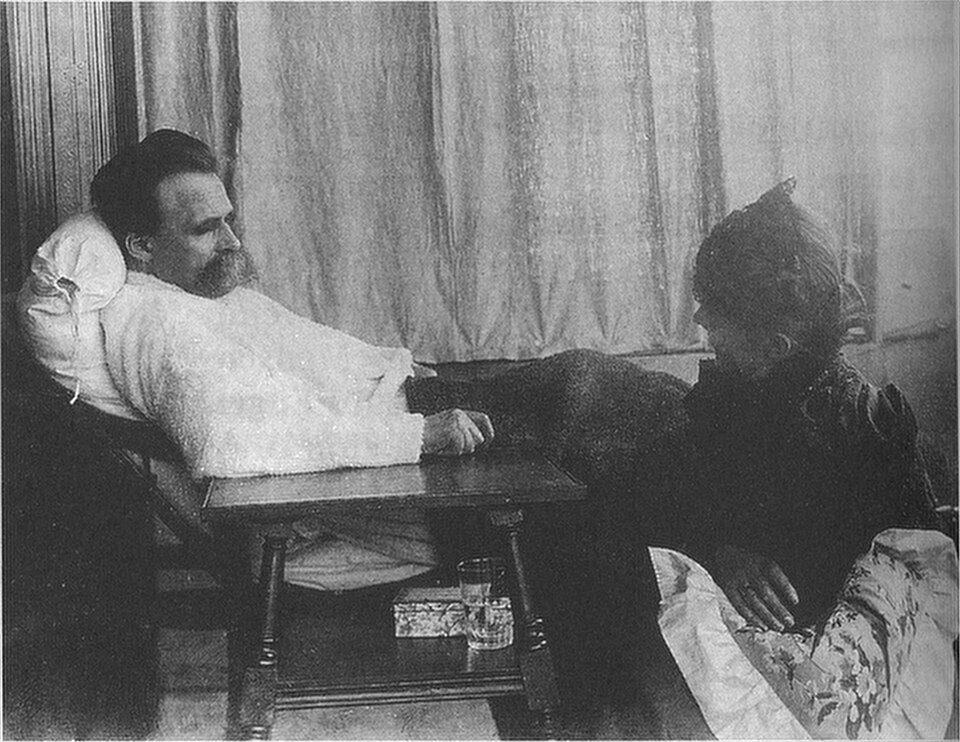

BS: I would definitely name another artist, that is Marcel Odenbach. He lived in Sils Maria during the corona period and worked in the Nietzsche room. The work is called View without God [Fig. 3] — a huge photo work that was created digitally. There you can see the Nietzsche Room as you know it... and every detail on this seemingly genuine but digital photograph is in itself a collage of other motifs. For example, Nietzsche's family, Nietzsche's letters, Nietzsche's compositions. You only see that when you stand in front of the picture. It's very big, it's full of walls. This means that, so to speak, the entire philosopher can be inferred from a single picture, and this includes this line of text: “When he found words again, he had nothing more to say.” — Of course, Nietzsche could not speak after his attack when he was in Turin, but when he found words again, he had nothing more to say. This alludes to the episode of the Turin Horse Hug.4 And now you have to imagine that the whole thing is a huge collage. It looks like a normal photo, but details are also hidden in the carpet and everywhere. There is a frieze at the top and this frieze is one portrait next to the other. Interestingly enough, there is also a fake. It's like a mosaic of Nietzsche texts, photos, trips, friends, relatives, acquaintances, Wagner... It all appears there, including the horse over and over again. I think they're all pictures of horses here on the left. So the famous episode when he supposedly hugged a horse in Turin, collapsed and then went insane.

JP: Who else should you know?

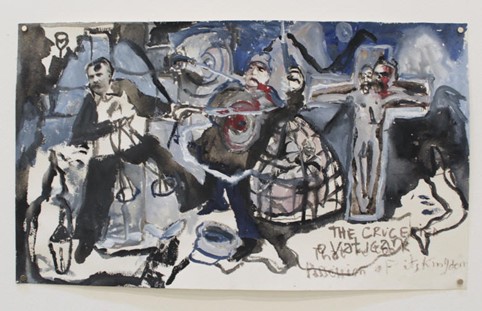

BS: It is absolutely impossible to imagine reception without Jonathan Meese [see fig. 4]. Then you should definitely know the series by Egyptian-Canadian artist Anna Boghiguian. She did a wonderful series called An Incident in the Life of a Philosopher [Figure 5]. It is only about his last days in Turin, this fateful episode, which for him ranges up to, how shall you say, metaphorical resolution of the apparitions he experienced there and which led him to write himself later in his insane letters as dionysus and The Crucified seen in a schizoid double role.

JP: What makes this work so special?

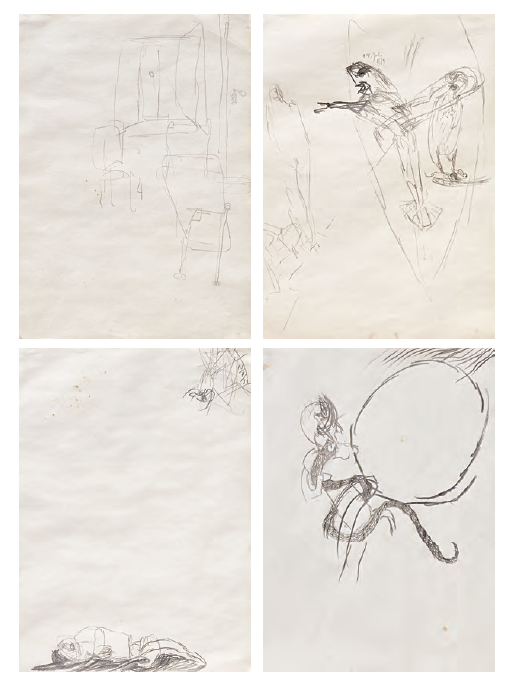

BS: ... The tremendous empathy that goes into it: on the one hand, understanding this episode, on the other hand, artistic free interpretation and how it works. She works with collage elements, some of which suggest authenticity. Then again, completely free interpretation. She virtually continues this legend. The question: How could this have happened? But then there are also flashbacks, just like in the movies. Suddenly Lou von Salomé appears and this famous Trio InfernalI always like to say, with Paul Reé. They wanted to start a residential community in Paris, but it was all very, very difficult at the time. Nietzsche had these plans, but there was a lot of jealousy and a great many misunderstandings, so that this friendship soon fell apart. But on the way to his madness, he virtually encounters this flashback again. And it represents it all. At the same time, she has written a poem in which she describes the incident as she feels about it. A great artist who has also been to the Venice Biennale. She is now an elderly woman, Anna Boghiguian, a very great artist. Then, of course, Felix Dröse, a Beuys student who made these blind drawings back in the 80s. That is in the chapter Being Nietzsche [Figure 6]. So that means how far do artists go...

JP: ... I remember an artist who put himself in Nietzsche's shoes.

BS: Right, so how far do they push this moment of identification? Of course, the question behind this is: How can I really understand Nietzsche? So not just his lyrics, but how can I understand this person in all his tragedy? How can I also understand the insane Nietzsche, who has also said interesting things from time to time, how can I understand him? And Dröse answered that for himself back in the 80s by blindfolding himself. Then the inner images that he had in his head after he had read the then newly published Nietzsche biography by Curt Paul Janz, called these three volumes before his mind's eye, so to speak, and put them on paper with blind drawings. Such intensive things were created there, totally intense pictures, which are very delicate because they are very bright pencil drawings. They are not as expressive as Meese draws them, but rather searching drawings, you could say. A searching line and yet it condenses into incredible images or even visions, where you take a keyhole perspective and look into this hospital room. Or once a figure, i.e. Nietzsche, is lying down on the ground in the hospital camp, and a black spider comes from above and approaches dangerously. This is, of course, the symbol of the mother, the spider as the mother animal, which did not let go of him until death even though she had already died in 1897. That is also a very, very big achievement, a very large series of 151 drawings.

6. “Art and philosophy are ways of ultimately reaching a life-affirming position.”

JP: At the beginning of the book and on the title, write “Nietzsche forever? “and answer the question at the end of the book with “Nietzsche forever! “, i.e. with an exclamation mark. In the book, you have already formulated the question yourself as to the future viability of this subject in contemporary art. What factors do you currently see there? What is missing now?

BS: I believe that the topic will continue to be worked on, because after the book was completed, I had found around ten new works that could be sorted into the 14 subject groups I found. One of them was about sexuality, another about what relics there are. But that would have been nothing new in that sense. So I don't think there's a whole new topic coming up now. Perhaps “Nietzsche and the natural sciences” or something like that. There is now a researcher who is investigating Nietzsche's statements about the climate, others are asking about Nietzsche's attitude towards food — this eternal search for the right diet: What is digestible for him, just as he was always looking for the right place where he could write in peace, where he could get a better grip on his headaches and eternal illness, his nausea and everything he had. It is possible that artists will pick up on this at some point. But they're not there yet... The art development or reception that artists have towards Nietzsche and biographical Nietzsche research are not on the same level. This means that if a young scientist suddenly investigates Nietzsche's statements about climate, it will take a while before they are received by artists, if they may find out by chance.

JP: Do artists work in such a way that they read for now?

BS: It can happen in multiple ways. It may be that they read Nietzsche himself, where he talks about the climate in the Upper Engadine, for example, during his travels. And if someone is now interested in science, then it may well be that he comes to it via Nietzsche himself or through scientific discussion. One example is Berlin artist Tyyne Claudia Pollmann — with these two large, very early digital works.

JP: Is that an animation?

BS: It's all computer generated. “Photobased art,” they say today — based on photographs, but everything built on a computer. Back then, in 2000, she worked with the latest American programs and is also an example of how a scientist, namely a medical doctor, deals with Nietzsche and also with the way of making digital art. So that means someone who advances into these realms and also looks at this saying by Nietzsche about art from the perspective of science and science from the perspective of art5 Take it seriously. It is a shining example of this.

JP: Can you further explain Nietzsche's future viability as a subject?

BS: This is also a central question posed by this artist, who is a professor at the Berlin-Weissensee Academy of Art. Nietzsche Bynite [Fig. 7] and Transfigure Nietzsche: It contains the term transfiguration, which of course has several anchor points in the work. (As a side note, because my book is about transfigurations). Transfigurations are changes in Nietzsche's figure through the eyes of artists. But transfiguration is also a term that Nietzsche himself uses. In the introduction, you probably mentioned his discussion with Raphael [Transfigurazione di Gesù] saw where he regarded this motif as an icon for himself.6 Transfiguration has become synonymous with Nietzsche's entire philosophy, so to speak. He sees philosophy and ultimately also art as an opportunity to affirm life on earth, human life in all its problems, ugliness, warlike, terrible forms, by, so to speak, transfiguring it. Art and philosophy are ways of ultimately reaching a life-affirming position. That is the core of Nietzschean philosophy, his philosophy of life: his affirmation of life, despite all difficulties and circumstances.

JP: Are you worried about how Nietzsche will be portrayed in art in 20 years?